RUSSIAN ICONS: SPIRITUAL AND MATERIAL ASPECTSVERA BEAVER-BRICKEN ESPINOLA

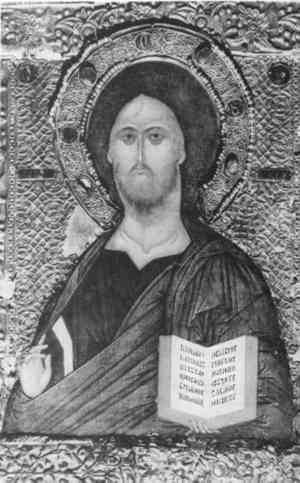

4 THE OKLADMetals were used in conjunction with wooden icons in Russia as early as the 11th and 12th centuries. 4.1 BASMA OKLADSEarly oklads were made of basma nailed to the margins and/or selected areas of the icon. Basma was a handstamped sheet of silver or silvergilt less than half a millimeter in thickness (fig. 3). The basma was often attached to the icon with small silver nails. Some basma oklads covered large areas of the icon, accounting for

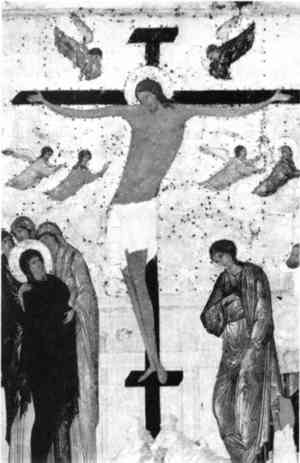

4.2 LATER OKLADSIn the 17th century, oklads were often made of one sheet of repousse� and chased metal that repeated the iconography. The metal was excised to expose faces, hands, feet, and other selected details of the icon it covered. Oklads were made of gold, gold-plated silver, solid silver, brass, or copper, silver-plated or plain, often with the addition of enamels, filigree work, pearls, and gemstones. They were sometimes adorned with added halos, crowns, and pendants. Although oklads were intended to beautify and protect icons, they sometimes provided a facade over only half-painted, mass produced icons in the 19th and 20th centuries. Nails used to affix the oklads or their additions often damaged the front of the icon, spalling paint and ground layers. Brass and silver nails caused mechanical damage, and iron nails often deposited rust. |