THE CARE AND CONSERVATION OF GLASS CHANDELIERSJULIE A. REILLY, & MARTIN MORTIMER

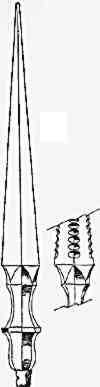

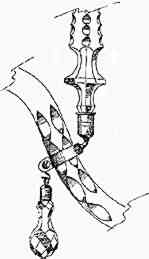

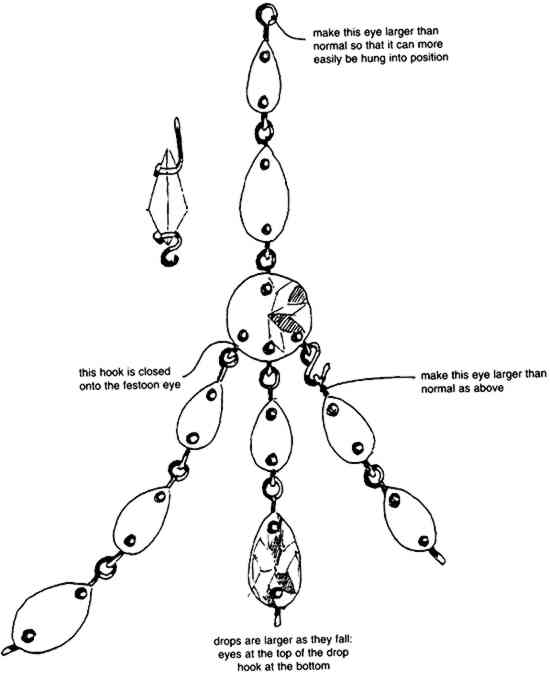

3 CHANGING STYLE AND THE GLASS CHANDELIERArchitectural styles were reflected in the progression of stylistic elements in chandelier design. The rococo style brought great elaboration to lighting devices, with double-curved arms and the addition of extra glass ornamentation in the 1760s. Separate decorative ornaments were introduced, such as spires (fig. 8) that could be affixed to the chandelier by mounts strapped to the arms (fig. 9). Other elements and drops were designed to hang singly from wires. Glass canopies were added to the central rod as stem-pieces in order to mount extra decoration that was hung from holes in the borders of the canopies (fig. 10).

The stems of neoclassical chandeliers (ca. 1775–1800) were arranged around a classical vase shape stem-piece. Chains of graded drops were draped symmetrically from the canopies and/or the arms, point to point, and linked by oval glass paterae drops (shown in fig. 12). Vertical prisms or spires of triangular section were added, normally mounted on small arms that alternated with those bearing candles. The prisms were initially notched like their contemporary arms or were, later, plain.

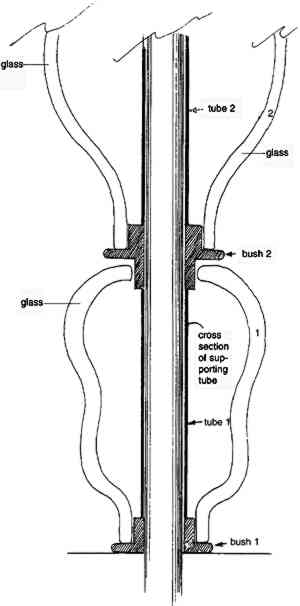

By the end of the 18th century, major changes were taking place in chandelier design, with metal frames gaining in popularity. These frames were dressed with cascading chains of graduated glass drops affixed at top and bottom. Glass stem-pieces thus became redundant, and the chains of drops themselves provided the form of the chandelier. From the main rim of such chandeliers, which have been termed “Regency” but which are more accurately called “frame” chandeliers, extended short arms of glass or metal that supported glass drip-pans and nozzles. The surface patterns and decoration of the drip-pans and nozzles developed in a 3.1 OTHER ORNAMENTATIONThe third quarter of the 18th century saw the greatest profusion of ornamentation before chandelier design fell under the influence of the neoclassical movement with its more limited design vocabulary. Most if not all of the elaborate and varied drops, pendant ornaments, and standing ornaments were cast into a basic shape before cutting. These ornaments included tall tapered prisms or spires. The variety of decoration on English chandeliers was, however, exceeded on the Continent, where the rococo style rose to even greater heights. There, pendant and standing ornaments were more frequently flat and often had patterns cast into one side. Elaborate floral or other elements were sometimes constructed with glass beads and wire. Unlike the English practice, continental spires The presence of flat drops with elaborate cut borders and wired beadwork ornaments is one of many indications of the probable continental source of a chandelier; however, one of the most secure indicators can be the variable fluorescence of different glass compositions under ultraviolet light. Virtually all 18th-century English chandeliers were of lead glass, and all continental chandeliers were of soda lime glass, which should exhibit differing colors of fluorescence when compared under ultraviolet light. As will be noted, ultraviolet light frequently also discloses incompatible replacements in a chandelier and can confirm the suitability or originality of some components. Above all, a knowledge of the evolution of chandelier design is essential for anyone who undertakes more than remedial efforts to return a chandelier to anything approaching its original state. 3.2 CONSTRUCTION OF THE SHAFTMaterials used in the construction of chandeliers (other than glass itself) varied little throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. The central rod was of iron, initially threaded along its entire length and later smooth with threading only where required for fitted bushings. Initially, the rods were wrapped in metal foil, perhaps tin, to give a silvery effect within the glass rather than the black of untreated iron. As the century advanced and supportive metal bushings to hold stem pieces were introduced, sleeves of silver-plated brass were substituted for the wrapped tin coverings. By the end of the 18th century, sufficient bushings or washers were included in the design to support the individual weight of most of the glass stem-pieces. This additional strength was achieved by providing a bushing with a turned rebate on its upper side to fit the hole in the bottom of the first glass stem-piece. A tube of a suitable diameter to be a snug fit over the iron suspension rod was cut and slid inside the first glass stem-piece. A second bushing was then turned whose lower rebate fit the hole in the top of the first glass stem-piece, and the tube was cut at a point that allowed that stem-piece to turn freely without obstruction from its associated metalwork. The top of the second bushing carried a rebate turned to fit the hole in the bottom of the second glass stem-piece, the weight of which was carried by the bushing supported on the tube within the first glass stem-piece (fig. 11).

The above description is significant, because the essential principle followed in assembling the somewhat heavy components in an early-18th-century glass chandelier shaft was to allow the weight of each stem-piece to be independently supported by a bushing affixed to the rod. In the late 18th century, not all parts were so supported. For instance, it was common practice in a neoclassical chandelier to have a single tube within a group of minor (and thus lightweight) glass stem-pieces, with a bushing at the central vase or urn to provide support. When chandeliers with glass stems reappeared in the second half of the 19th century, it was typical to provide every glass stem-piece with its unique, numbered metalwork. The metalwork of a glass stem should always be numbered. The usual formula is to use numbers from the arm plate upward and letters from the arm plate downward. Numbers are normally stamped on the upper end of the stem tubes (not essential) and on the upper faces of the stem bushings (essential). Ideally, all metalwork should slide into position above the arm plate, with the possible exception of a final threaded fitting below the top shackle with its terminal nut and stop-screw. All washers or bushings supporting glass stem-pieces below the arm plate should be threaded. Thus, when assembling a chandelier, all of the upper parts of the stem are put together before hanging, and the lower parts are added singly, each held in proper place with a threaded washer or bushing. |