PRIOR REPAIRS: WHEN SHOULD THEY BE PRESERVED?JEAN D. PORTELL

4 REPAIRS THAT HAVE CULTURAL OR SPIRITUAL VALUEDecisions about whether to retain or reverse existing treatments on objects from other cultures are commonly based on the opinions of the present caretakers about the appropriateness of the repairs. Increasingly, owners and conservators are seeking the advice of a responsible member of the originating culture or of a scholar who has studied that culture.

4.1 ZUNI WOODEN WAR GODSIn many cultures there are certain objects that are considered sacred, that is, they serve a religious purpose. One of the earliest American conservation articles to stress the importance of this intangible component of such artifacts states that “we should reconsider the circumstances under which sacred objects undergo modern, scientific conservation treatment, since the very process of handling, documentation and treatment could constitute interference with the integrity of the object and destruction of its functional and spiritual value” (Wolfe and Mibach 1983, 1). The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990 forced owners and conservators to accept that in some cases even simply storing a sacred object indoors might not be acceptable. The year after NAGPRA went into effect, a journalist reported that a group of 13 ancient Zuni wooden war gods being repatriated from the Brooklyn Museum to the Zuni tribe in New Mexico would be placed outdoors and permitted to deteriorate naturally according to tribal custom (Miller 1991). One could interpret this move as an intentional reversal of the previous treatment (preventive care by protection from weathering) based on spiritual exigencies of the originating culture.

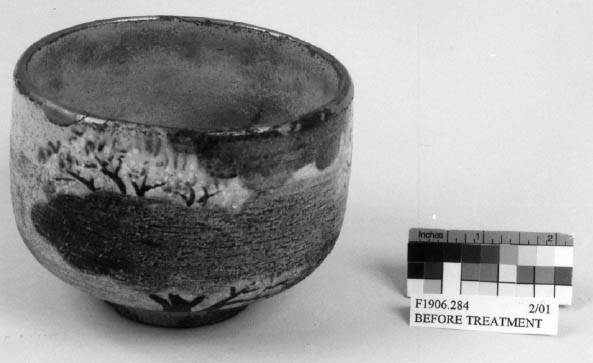

4.2 TWO JAPANESE TEA BOWLSTwo Japanese Kenzan-style tea bowls owned by the Smithsonian Institution's Freer Gallery of Art have old repairs. In preparing these 19th-century

The entire rim of tea bowl no. F1906.284 (fig. 5) had been repaired with red lacquer coated with gold. These old repair materials now have fine cracks, and a few areas of the lacquer have begun to lift away from the ceramic. Because the prior repair was deemed culturally appropriate in both style and materials, the new treatment was limited to stabilizing it by applying a synthetic resin to areas of the lacquer that were cracked or lifting. The old repair of tea bowl no. F1911.509 (fig. 6) was very different. Small chips and large mended breaks in the broken bowl had been painted with an excess of a silver-colored metallic paint that was soluble in organic solvents. In both style and material, this crudely applied repair was at odds with the Asian traditions of ceramic restoration. Therefore the decision was made to re-repair the bowl using modern techniques and materials. 4.3 KIOWA BEADED CRADLEThe Kiowa and Comanche peoples made elaborately decorated cradles for their babies during the reservation period (1860s–ca. 1920). According to Barbara A. Hail, deputy director and curator (now curator emerita) of Brown University's Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, this type of cradle was culturally significant as a marker of earlier times before these peoples were defeated by the U.S. Army and began to lose their cultural identity (Hail 2000, 2002). A particularly fine example is the Kiowa lattice cradle that a woman named Hoygyohodle (1854–1938) decorated for the baby of one of her relatives (fig. 7). This well-documented cradle is constructed of two boards 119 cm long joined in a narrow V shape to support a deerskin and rawhide form for holding the baby. The outside of this form is entirely covered with colored-glass seed beads sewn on in an abstract pattern.

The beading on the Hoygyohodle cradle had been restored more than once, and more beads needed to be replaced before an exhibition that traveled from December 1999 to January 2002. According to Hail (2002), Alexandra Allardt O'Donnell, the Haffenreffer Museum's consultant conservator, contributed to the cradle's conservation by doing some stabilizing work and adding some stuffing, but she neither removed nor added any beads. Rebeading (to fill losses) was done by Vanessa Paukeigope Jennings, a Kiowa cradle maker who was brought to the museum to do this work under O'Donnell's supervision (fig. 8).

O'Donnell explained (2002): “We kept the old beading repairs as they represented a continuum of

|