PRIOR REPAIRS: WHEN SHOULD THEY BE PRESERVED?JEAN D. PORTELL

5 TREATMENTS PERFORMED BY OR FOR ARTISTSArtists sometimes repair their artworks while they still own them or when they are invited to do so by subsequent owners. Sometimes artists also treat the creations produced by other artists. When an object that needs conservation has been previously repaired by a professional artist, it is prudent to investigate the circumstances thoroughly before proceeding.

5.1 ANDREAS LOPEZ'S PAINTING SOR PUDENCIANAOlana, located near Hudson, N.Y., is the former home of the artist Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900) and is now a New York State Historic Site. On exhibition at Olana are paintings by Church and other paintings that he collected. Among the

When the painting was surveyed at Olana in 1989, Zucker and Olana's site manager and curator jointly arrived at the decision to leave the painting looking much as it must have after Church's treatment. According to Zucker (2002), all three felt that, in the context of its present setting, it was more important to preserve the portrait's appearance as Church had altered it than to inpaint the losses.

An article that describes how Church purchased and then cleaned the painting was found by Gerald L. Carr, an independent art historian, when he was doing research for his Catalogue Raisonn� of Works of Art at Olana State Historic Site (University of Cambridge Press, 1994). This article appeared on the front page of the March 16, 1895, issue of Two Republics, an English-language periodical that was published in Mexico City from 1867 to 1900. Zucker provided me with a photocopy of the microfilmed periodical, which is difficult to read because of bleed-though ink staining.1 (The last two letters of the

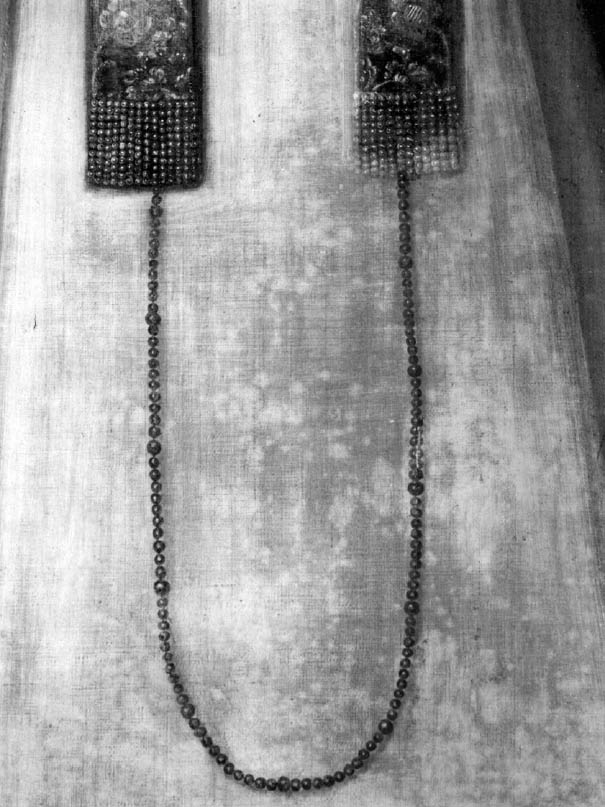

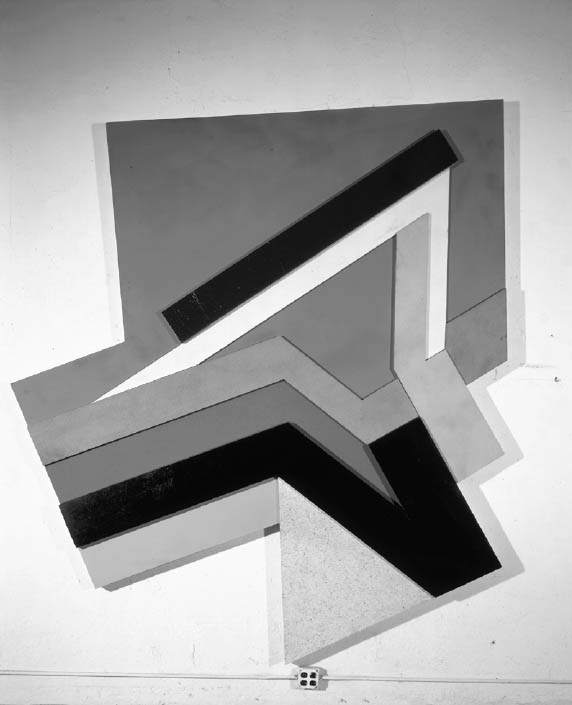

One of the great delights of Mr. Frederick [sic] E. Church, the celebrated landscape artist, when he is in Mexico, is to snoop around the bric-a-brac stores seeking what he may purchase. Sometimes it may be a bit of jade centuries older than the conquest, a proof, may be, of commerce with South-eastern Asia, a statuette of the Virgin by Tresguerras, sometimes a good bit of pottery, occasionally a book with rare engravings. For the first time a week or two ago, he purchased a picture, which though grimy with dirt and discolored varnish revealed to his artistic eye certain qualities which only a good painter could possess. It was a portrait of a young lady in the costume of a novice, and there was a long statement at the bottom, which required to be cleaned before it could be deciphered. The great artist has a passion for mending and repairing things, and he was convinced that if this picture were relieved of its dirt and varnish, it would be of such merit as to make it worth his while to patch up its numerous tears and make it ready for framing. To clean it, he used an invention of his own, a mixture of alcohol and castor oil, which when combined form a gummy grease of the most efficaceous character, innocuous to paints generally, with the exception of one or two earths which disappear with the dirt. For several days he was invisible, and when his friends were admitted they saw the result of his labors, though the picture still remains under the disadvantage of not having been revarnished. It is a life size portrait of Sister Pudencia [sic] Josefa Manuela del Corazon de Maria, … who was born May 19th, 1757, and took the vow of a Nun of the Convent of the Incarnation of this court of Mexico August the 15th, 1781, and made her solemn profession … Sunday August 25th, 1782. Andreas Lopez was the painter according to the signature which the cleaning revealed, and the writer remembered to have seen the name in a list of painters whose works existed in the city of Puebla. The existence of this contemporaneous account influenced the choice not to inpaint losses sustained during the old cleaning of the portrait of Sor Pudenciana. Because the painting hangs in Church's home, and because he was the painting's collector and restorer, the team at Olana considered it more important to preserve the visual evidence of Church's involvement than to preserve the intent of the artist who created the painting. 5.2 FRANK STELLAThe decision to preserve or replace a prior repair must take into consideration the opinion of the artist whenever it is possible to know this. The opinion of the artist is especially important when the artist is living, because he or she may provide important technical information about the object's materials or construction. There is also a legal reason to seek the artist's views: federal law and some state laws protect an artist's right to control the appearance of his or her artwork. The artist Frank Stella, in a telephone conversation with the author on March 7, 2002, said that for many years he avoided the subject of restoration, and now he believes that it might have been better to discuss it openly. For example, he explained that sometimes an owner of one of his pieces tries to persuade him to repair it. “They think it's worth more if the artist fixes it. That's not true. … It's dangerous!” Asked whether he had ever repaired his own work, Stella laughed and said, “I've done it about twice, and I've just ruined it. Fortunately, I worked on pieces that I owned.” He mentioned also that he has made creative changes while restoring one of his artworks from an earlier period. Would Stella want his repair to remain, if an object that he had restored required more restoration later? His response was to emphasize what is most important to him. Referring to a series that he made using felt covers (Polish Village Series, 1970–73, fig. 11), the artist remarked that when the original felt

5.3 GABRIEL OROZCO'S SCULPTURE RECAPTURED NATUREWhen artists work with untraditional materials, conservators may be forced to seek untraditional methods of art preservation. If the artist is living and wishes to cooperate with the preservation of a fragile artwork, the best result may come from a collaboration among the artist (possibly also his or her fabricator), the sculpture's owner (or authorized agent), and the conservator. A case in point is how to preserve Gabriel Orozco's Recaptured Nature (fig. 12). This is an abstract inflated form made of inner tubes of truck tires fused together with vulcanized natural rubber. The object was fabricated for the artist in Mexico City in 1990 in a shop near the artist's studio. When the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA) acquired the sculpture in 1997, the artist had already given specific instructions for repairing leaks in the seams: repairs can be made as long as the patches are oval and made from black rubber. According to Michelle Barger, SFMoMA's associate conservator of objects, the vulcanized rubber that was used to make the original seams has embrittled faster than has the rubber of the inner tube tires. Although the sculpture has been patched by previous owners, new holes continue to develop in the seams (fig. 13). Before this sculpture can again be inflated and exhibited, it will have to be re-treated. Barger explained the museum's point of view:

|