PRIOR REPAIRS: WHEN SHOULD THEY BE PRESERVED?JEAN D. PORTELL

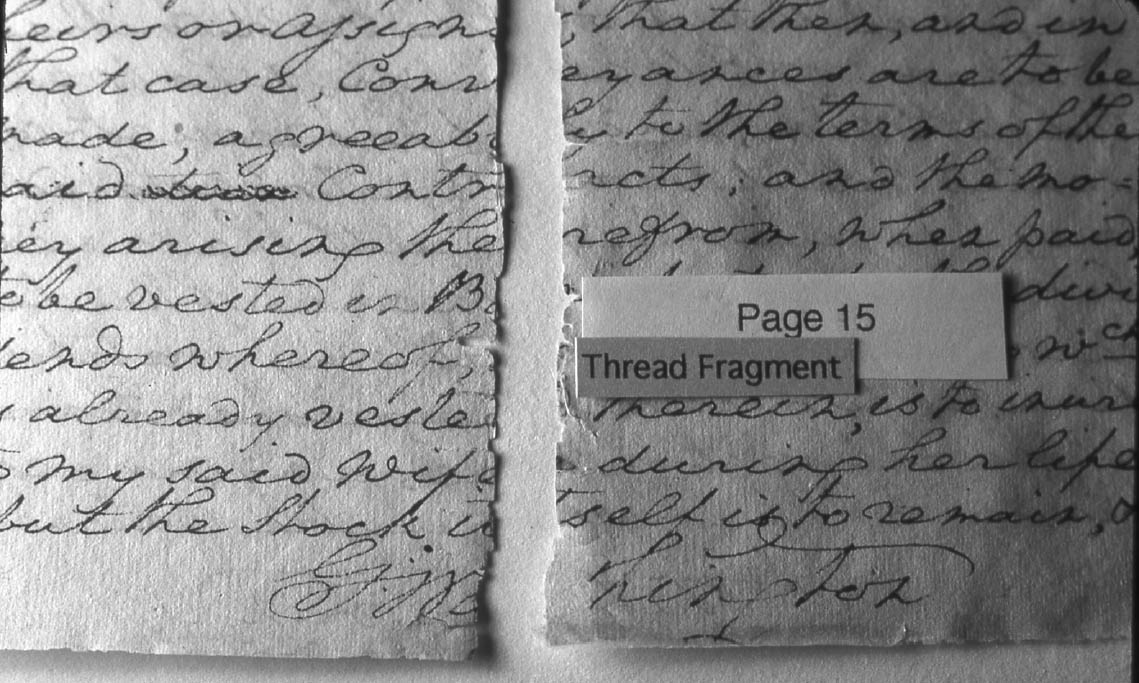

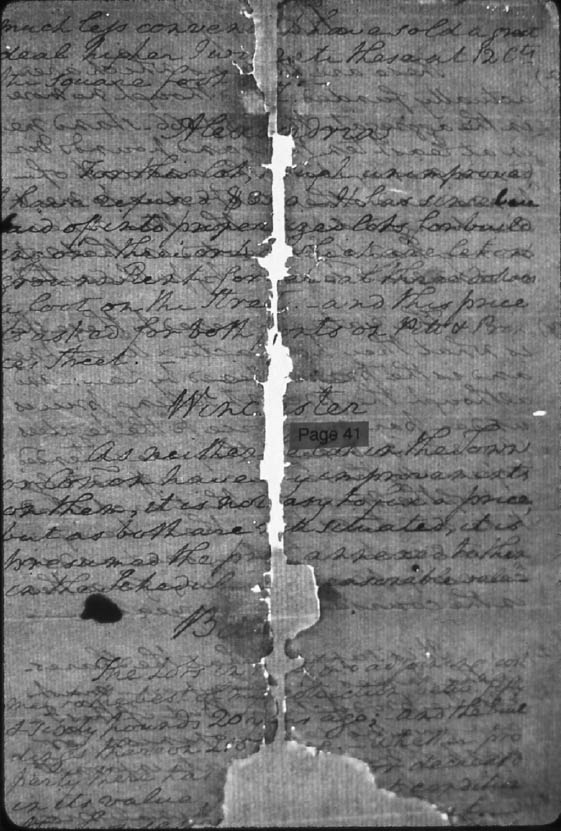

3 REPAIRS THAT HAVE HISTORIC VALUESometimes repairs provide eloquent mute witness to the history of a damaged object. The circumstances that led to the repair, or the person who applied it, can be linked with notable historic moments. Even when the origin of an old repair is uncertain, it can attain the status of an essential attribute. In such cases, noticing the prior repair can enhance a viewer's enjoyment of the object. 3.1 GEORGE WASHINGTON'S WILLChristine Smith, president of Conservation of Art on Paper Inc., dedicated more than three years to conserving George Washington's last will and testament, completing her work in 2002. The 44-page will is owned by Fairfax County, Virginia, where it was filed shortly after Washington's death in 1788. During the Civil War, this historic document was folded, moved about, and even buried in a wine cellar. Its pages sustained various damages, including tears that were secured by sewing. Later, in 1910, the will received its first professional conservation treatment from William Berwick (1848–1920), manuscript restorer at the Library of Congress (Ginsberg 2000; Smith 2002). The recent treatment by Smith preserves many of the earlier repairs, such as the thread remnants of sewing mends that date from the Civil War and the fills of fine, well-matched laid paper that Berwick added to the larger losses. The stitching holes and thread remnants (fig. 1) are part of the document's history. They are evidence of the struggle to keep it safe in trying times. Berwick's fillings (fig. 2) are historic for another reason. They reveal that Berwick's work was at the threshold of modern paper conservation in the United States. But Smith reversed other repairs. Silk sheets that Berwick pasted over the front and back of each page to reinforce it eventually stiffened and darkened the sheets, prevented adequate repair of underlying areas, and obscured the writing, so all the silk was removed, as were scattered localized transparent-paper reinforcements that had discolored some pages and caused some to warp. Smith worked closely with the owner and other knowledgeable advisers when she planned the will's treatment. She had specific reasons for deciding which prior repairs to retain, stressing aesthetics and stability and also the desire to preserve the beautifully made fillings that Berwick applied almost a century ago and that have remained in excellent condition. But to this author she spoke of wishing that there were a less subjective way to make such decisions (Smith 2002). 3.2 HOPI KACHINAAn old repair, especially one that may have been made by or for the object's original owners, can gradually become an accepted attribute. The Brooklyn Museum owns a collection of Hopi kachina dolls that were acquired in 1904 by curator Stewart Culin for the museum's new department of ethnology. Culin purchased the lot from Wetzler Brothers, a store in Holbrook, Arizona. Among them (fig. 3) is a kachina that represents Kokopol (an erotic personage sometimes called Kokopelli) that has an obvious break through its right arm. The forearm is secured with a hide thong inserted through horizontal holes on either side of the break and knotted on the inner side of the elbow. The museum's archivist, Deborah Wythe (2002), found no specific reference to the repair in the museum's earliest records of this figure, which are in the 1904 Stewart Culin Expedition Records. A later (undated) departmental catalog card notes the existence of a thong repair. Eventually, as notes were added to the records of this object in the 1980s by research associate Ira Jacknis, they started to refer to a “possible native repair“ (Wythe 2002). Museum conservator Lisa Bruno shared with the author the latest conservation records of this kachina, which include a 1991 treatment report (filed in the Conservation Department, Brooklyn Museum of Art) by conservator Tina Krumrine. Krumrine here notes two prior repairs of breaks through the figure's right arm. She refers to the old visible repair with a thong as a “native repair,” in contrast to another break repair near it, which had been rejoined inconspicuously using a synthetic resin emulsion (fig. 4). Neither break was re-repaired in 1991 when the kachina received

|