THE AMERICAN ARTIST'S TOOLS AND MATERIALS FOR ON-SITE OIL SKETCHINGALEXANDER KATLAN

2 IMPORTANT TECHNICAL INVENTIONS2.1 THE COLLAPSIBLE PAINT TUBEWhat 19th-century technical inventions changed the artist's craft? The collapsible paint tube, invented in 1841, made on-site oil sketching an easy reality. It replaced the traditional leather bladder pouch, which was difficult to maneuver. John G. Rand, a minor American artist in London, devised the first collapsible paint tube, initially marketed by Thomas Brown, a London-based colormen firm (Harley 1971). Rand was issued two patents by the British patent office. The first (March 6, 1841, #8863) was for “Improvements By 1842, the tube was being sold exclusively by the firm of Winsor & Newton as “Rand's Patent Collapsible Tube” (Faibairn 1983). By the 1850s, the Winsor & Newton Collapsible Paint Tube (note that “Rand” has been dropped) was being advertised in the trade catalogs of New York firms such as Goupil & Co. and Masury & Whiton (New York City Directory 1858) and also in Paris in the earliest of the Sennelier catalogs of 1887 (Ahearn 1997). Other technical advances include the portable easel (Goupil & Co. 1857), which appears in the Bierstadt painting Cho-looke, The Yosemite Fall; the portable stool seen in this painting, also listed in a later catalog, is from the firm of S. & H. Goldberg (successors to A. Sussmann) of the late 1890s (S. & H. Goldberg & Co. ca. 1890)(fig. 3).

2.2 THE METAL BRUSH FERRULEPerhaps the most important and underrated development was the change in brush ferrules from quill, thread, or wire-bound brushes to metal ferrules, making paint brushes sturdier and less subject to damage. Probably introduced in the 18th century, the metal ferrule gained popularity in the 19th century. Mechanization eliminated the time-consuming and expensive operation of binding the hair to the handle by hand. Initially, the metal ferrules were glued to the handles, and as moisture penetrated the wood handles the brush heads simply fell off. This prompted the development of the crimp, the indentation in the ferrule that secures it to the handle. In the 19th and early 20th century, some metal ferrules were nailed onto the handle, while some had single or multiple crimps (Pinney

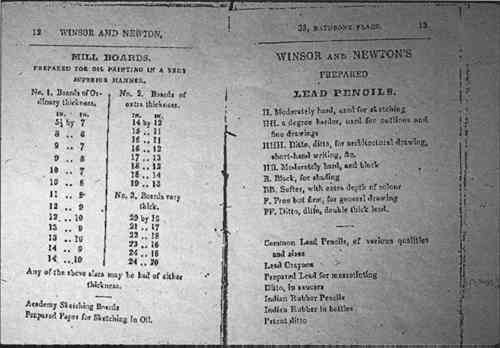

2.3 PAINTING SUPPORTSThe major 19th-century technical advance was the invention of alternative painting supports. The traditional canvas or wooden panels were heavy, clumsy, and inconvenient to transport. Canvas could be punctured and panels could be scratched in transport. New lightweight, inexpensive supports were developed, such as millboards, academy boards, canvas boards, oil sketching paper, and oil sketching blocks. Japanned tin boxes and kits were created to hold these new supports (C.S. Samuel & Co. ca. 1884). 2.3.1 Solid Sketch BlocksThe solid sketch block (M. Knoedler & Co. ca. 1870) was an unusual development in the 1840s and 1850s and was originally developed for on-site oil sketching and drawing. These blocks consisted of a number of sheets of paper compressed and in some cases glued or pasted around the edges. A single sheet could be separated by passing a knife under the edges of the paper (Goupil & Co. 1854). This type of sketchbook became very popular and was offered by both European and American In two known cases, American artists painted in oil on this solid paper block partially because they liked the smooth tooth of the paper. The Doctor (1873, New York State Museum, Albany, N.Y.) and The Arno Florence (1863, National Academy of Design, New York, N.Y.), both by Edward Lamson Henry (1841–1919), were executed on this support. Albert Bierstadt commonly used paper supports for his oil sketches, although he or his dealers subsequently mounted the paper onto canvas, panels, and stretcher supports. The uniform size of some of Bierstadt's oil sketches possibly suggest that they were done on solid sketching blocks. The trade catalogs list sizes ranging from 5 � 7 in. to 14 � 20 in. (12.5 � 17.5 cm to 35 � 50 cm) (William Schaus & Co. 1868). Many of Bierstadt's oil paper sketches measured 14 � 19 in. (35 � 47.5 cm), suggesting that these papers were slightly trimmed during the mounting process. 2.3.2 Academy Boards and MillboardsThe more important lightweight sketching supports in the 19th century were academy boards and millboards. According to Gettens and Stout (1966, 221), “Millboard is a generic term covering a wide range of hard, pressed, flexible paste boards. Millboards were first introduced in the late 18th century by English colormen firms although their popularity was in the 19th century. Millboards were shown to be in existence in the early trade catalogs of Charles Roberson & Co. in 1819.” Designed as cheaper alternatives to wooden panels, they utilized mill and paper waste and were offered in various thicknesses. Sometimes the terms “stout” and “extra stout” also appear in the literature. The Winsor & Newton catalog of ca. 1835 uses the terms, “Boards of Ordinary Thickness,” “Boards of Extra Thickness,” and “Boards Very Thick.” This distinction does not appear in later Winsor & Newton catalogs. However, a George Rowney & Co. catalog of 1892 continues to indicate thickness, stating “Prepared Millboards for Oil Painting. No. 1 of Ordinary Thickness, No. 2 of Extra Thickness, No. 3. of Double Thickness” (fig. 5).

Inconsistency in the use of coating on the back of millboards and academy boards has resulted in confusion when differentiating the two. Such differentiation may not be possible on the basis of preparation, composition, or thickness. Millboards and academy boards were both coated on the front surface and back by the colormen firms manufacturing them. The front surfaces were sometimes smooth and sometimes stippled. Millboards became thinner toward the end of the 19th century, with the choice of “stoutness” no longer available, while academy boards became more robust and thicker. The gray protective priming on the back of wooden panels, millboards, and academy boards seems to have been fairly common practice with such colormen as Brown & Davy, Winsor & Newton, and George Rowney. Differentiation by priming and composition is not possible due to trade variations from numerous manufacturers, while differentiation by size might be possible because academy boards were initially made only in smaller sizes. However, by mid-century, academy boards were much larger in size. The American colormen firms were not as consistent in manufacturing millboards and academy boards as the English firms. For the English colormen, millboards were considered to be a higher-quality product, containing rag and linen fibers and having better-quality preparations. This quality distinction appears to have been lost among most American firms. By 1857, Goupil & Co. was offering “English” and “French” millboards. The “French” millboards were available in “graduated tints” and “plain” surface, while the “English” millboards were available only in “plain” surface (Goupil & Co. 1857, 12). This trade catalog is evidence of the American supply firms' interest in tinted preparations on millboards and the beginnings of texturization of surface; “plain” can imply a flat or smooth surface as well as an uncolored, white surface. The white surface gessoes became more popular in the mid-19th century. The tinting of the ground is purported with the French-type board. Greater confusion exists with academy boards, especially in trying to define exactly when they were invented. Gettens and Stout (1966, 221) state:

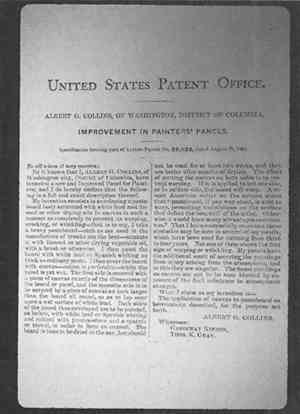

The statement that academy boards were introduced in England ca. 1850–52 and in the United States by ca. 1868 is inaccurate. Research shows that academy boards were available from Winsor & Newton as early as ca. 1835 and were probably available when the company was founded in 1832 (Winsor & Newton ca. 1835). Academy boards probably were available in England at the turn of the century and definitely by the 1820s (fig. 5). Although academy boards were manufactured in the United States by E. H. Friedrichs & Co. in 1869, the A. C. & E. H. Friedrichs Company did not exist before 1900, although the Ernest H. Friedrichs Company did exist in 1869 at 177 Bowery Street, New York, New York (Katlan 1987, 105). Other American colormen firms offered academy boards to artists at a much earlier date. The Edward Dechaux catalog of 1860 lists this board, although the ca. 1840 catalog does not list it. The early Goupil & Co. catalogs of 1854 and 1857 also list academy boards, the source being Winsor & Newton of London. It is also listed in the early William Schaus catalogs of the 1850s, with no source given. As its name implies, academy boards were an inexpensive, thin, semirigid support created for students in schools, academies, or universities. They were not originally intended for the professional artist's use in quick oil sketches and studies. The popularity of academy boards grew as art became part of the public school curriculum. They were a cheaper, disposable alternative for an oil painting support than prestretched canvas or wooden panels. Academy boards probably were made of pulp board and coated with a thick priming on the surface, generally a pale gray or white ground of lead pigments to stiffen the board. In most cases the boards were coated on the back with the same gray priming. Pulp boards were a variety of thick cardboard of inexpensive grade, made of pulp rolled into sheets, as opposed to pasteboards, which are formed by pasting sheets together. The surfaces of the academy boards were generally not covered by fabric, although artists in the early to mid-19th century sometimes covered these boards with fabric. It is not known whether an early colormen firm might have applied fabric to an academy board surface. Academy boards were initially made in smaller sizes—6 � 9 in. (15 � 22.5 cm), 9 � 12 in. (22.5 � 30 cm), 12 � 18 in. (30 � 45 cm), and 18 � 24 in. (45 � 60 cm), and they were rarely offered in a variety of thicknesses. By mid-century, “extra sizes,” or larger sizes, were commonly sold: 22 � 27 in. (55 � 67.5 cm) and 23 � 30 in. (57.5 � 75 cm). According to the Winsor The American colormen firms might have purposely blurred this distinction in order to offer academy boards at higher prices. At first they were sold by the dozen, as seen in the Goupil & Co catalog (1857). By the 1890s, academy boards were being sold individually, although still in limited sizes, from such geographically diverse firms as Frost & Adams of Boston and A. H. Abbott of Chicago. Academy boards were widely accepted by the professional artist with the increasing popularity of on-site oil sketching. However, artists began to notice problems with the support. With the heavy layering of the preparation and then a heavy layering of the oil paint, the thin paperboard tended to warp and sometimes even twist. Mechanical damage and dents easily caused the thick ground layers to crack and flake, leading manufacturers to coat the back of the board in an attempt to thicken and stiffen it. Because of these problems, academy boards were gradually being replaced by canvas boards by the end of the century; in fact, Winsor & Newton's London-Oil Sketching Board (a canvas board) was advertised as “superior to academy boards” (Frost & Adams ca. 1895). 2.3.3 Canvas BoardsSimilar confusion exists about the invention of canvas boards. The interest in the texturization of the board surface explains the development of canvas boards, that is, to achieve a canvas weave on a board. Gettens and Stout (1966, 221) state: “Canvas board, a paperboard with primed canvas fastened to one face, was put on the market by George Rowney and Company. Ltd. in 1878. It appears in the records of Reeves and Son, Ltd. and Winsor and Newton Company, Ltd. in 1884. C. Roberson and Company, Ltd. thinks that it was introduced between 1875 and 1880.” Although it is possible that canvas boards were introduced in England in ca. 1875–80, there are indications that they were introduced in the United States at a much earlier date. This confusion about the dating is probably due to the great popularity of the American Russell canvas board, which was widely marketed first by Janetzsky & Weber Co. and later by Frederick Weber & Co. of Philadelphia (Gettens and Stout 1966, 221). However, on August 25, 1863, a good 15 years before the Rowney catalog listings and before the “Russell board,” Albert G. Collins of Washington, D.C., patented an “improvement in painter's panels” (Collins 1863)(fig. 6) that consists of canvas applied to pasteboard in order to prevent the panel from “warping, cracking or wrinkling.” Obviously, by 1863, academy boards and millboards were beginning to exhibit warping problems due to the thinness of the cardboard supports and the hygroscopic glue sizing. Collins (1863, 1) states:

The Collins patent relates to a panel, similar to an academy board, with a smoother surface than the later texturized canvas boards with which we are more familiar. The Russell canvas board was first patented on March 18, 1879, and assigned for marketing first to John W. Shepherd and later to the firm of Frederick Weber & Co. (Russell 1879, 1). The Russell patent differed from the Collins patent in that it “consists in first pasting canvas or other suitable textile fabric to straw-board or other pasteboard, then drying the same under pressure, then painting the surface of the tablet with any desired pigment, and finally stippling the same to form a grain” (Russell 1879, 1). Russell was aware of the inherent instability and problem with straw-boards and he states, “Although straw-board of itself is liable to warp, the fabric applied to it with cement and under pressure renders it rigid and permanent, especially if the fabric be secured to both sides” (Russell 1879, 1). This patent indicates that by 1879 in the American market, precolored (pretinted) and texturized surfaces were beginning to be applied to panels. On the one Russell canvas board that I have examined, the back is covered with canvas and red paint. The front is covered with a slightly texturized gray surface. The extensive popularity of this board is suggested by the numerous trade catalogs that sold the Russell board (C. S. Samuel & Co. ca. 1884; A. Sartorius 1890–94; A. H. Abbott 1900). Frost & Adams (1895) describes the Russell board as “very desirable for outdoor sketching in oil,” while Frederick Weber & Co. (1929) says it is for outdoor sketching as well as studio painting. A. H. Abbott (1900, 18) simply states, “Prepared Linen on Heavy Board.” Numerous imitators of the Russell board began almost immediately. Winsor & Newton (1886, 84) advertises “canvas boards,” while George Rowney of London (1892, 156) states: “These boards present a surface of the best primed canvas, and from their neat and portable form are undoubtedly the very best kind of sketching board ever introduced.” The James Newman firm of London (1910, 163) describes the board as, “Best quality millboards covered with prepared canvas.” Interestingly, the American firm S. & H. Goldberg of New York (successor to A. Sussman) advertises a canvas board in 1884 (S. & H. Goldberg 1884). However, it is unclear whether this board is of their own manufacture or a Russell board. |