RUSSIAN ICONS: SPIRITUAL AND MATERIAL ASPECTSVERA BEAVER-BRICKEN ESPINOLA

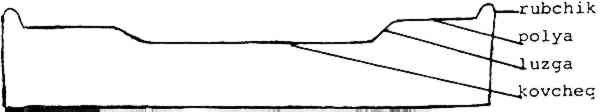

ABSTRACT—A sensitive, ethical, and informed approach is particularly welcome in the field of Russian icons because of diverse needs, opinions, and techniques within the disciplines of conservation and restoration. This paper reviews the spiritual and material aspects of Russian icons, presents an opinion based upon an ethnographic object conservation orientation, and calls for a future dialogue. 1 INTRODUCTIONDerived from the Greek eikon, an icon in its broadest definition is any image or portrait figure. According to Christian tradition, the earliest icon was an image of Christ's face left on a cloth variously called Veronica's Veil, The Holy Mandylion, The Vernicle, or as referred to in Russian, The Image Not Made with Hands. Many early Christian icons were painted, but many others were also made of mosaics or metal by repouss� and chasing, or casting, or by carving in stone or ivory. When Russia was baptized into the Eastern Orthodox faith in 988, it adopted these icon forms and more, such as embroidered textiles, enamels, and carved bone and wood. Because the topic is so broad, this paper focuses only on Russian wooden icons painted in tempera and their metal oklads (covers). 2 THE SPIRITUAL ICONAfter the great iconoclastic controversy in the eighth and ninth centuries, the Eastern Orthodox church formulated a doctrine of veneration of icons and also a set of technical rules for their artistic production. An authentic Russian icon is still created solely for religious veneration by a person considered morally upright who also is blessed to this purpose by a priest. Old icons were never signed since each was considered equally good, equally spiritual, and not a work of art. An icon is blessed upon completion and probably many times more, for in the course of its existence it may reside in many homes, churches, museums, and other places throughout the world. Each time it is reconsecrated to God it also becomes the intimate icon of a new people or location. Even if desecrated, the blessed icon never loses its sacredness, regardless of its situation. Russians present icons in baptism, marriage, as memorials for the dead, in thanksgiving, and for protection on a journey or in battle. Icons are used in churches and homes where candles and incense are burned near them and where the faithful kiss and touch them in acts of veneration and respect. Icons are never worshiped but considered a source of spiritual awakening, divine energy, and even miraculous events. Icons have become testaments of Russian faith, culture, and history. 3 THE MATERIAL ICONThe physical creation of an icon is steeped in tradition: “Every small item in an icon has meaning and every line has a reason for being” (Ovchinnikov 1980). 3.1 THE PANELLime, pine, spruce, and larch are the woods most commonly used in the construction of old

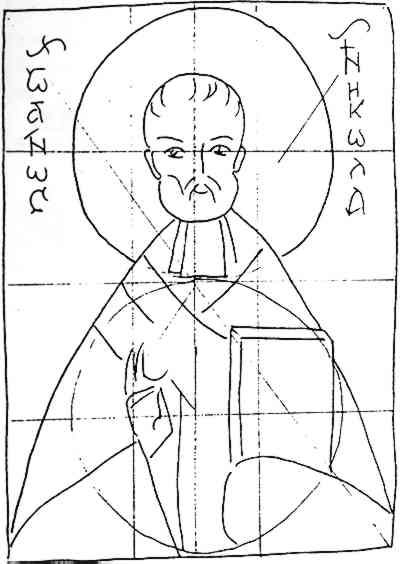

When the panels were completely seasoned and carved, the front was scored for the application of the linen and gesso. Gesso was made of a finely ground chalk or gypsum mixed with a glue. 3.2 THE GOLD LAYERNormally, gold leaf was used for the background of an icon. Gold projects light and is equated with the light of God. Gold with a greenish tone (mixed with silver) is seen on very early icons of the 11th-century. On later icons, the gold was more often a bright yellow with a slightly reddish tint (the addition of copper). A pale gold, almost electrum, provided a light background with a silvery sheen. In the beginning of the sixteenth century, Russian icon painters used thin sheets of silver with a thinner layer of gold beaten into it, so that one side became silver while the other was a very pale, whitish-looking gold. After the eighteenth century silver leaf was sometimes covered with a reddish shellac to produce a tint that looked like gold. When the overlying linoxyn darkened, it was difficult to clean without exposing the silver. Many such icons were severely damaged by restorers unaware of the delicate technique. 3.3 PAINTING THE ICONThe drawing of an icon was said to be measured in thirds (Ovchinnikov 1980)(fig. 2). An outline of the subject was often made with charcoal mixed with egg yolk.

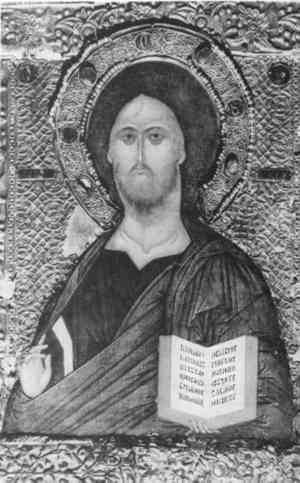

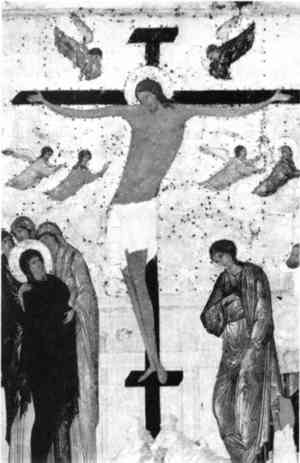

Some artists used paper tracings by making their own or using podlinniki, which were books containing a collection of patterns intended as guides for icon painters. The practice of tracing was associated with the Stoglav Council of When the background was of metallic leaves, the lines of the halos, faces, and figures were incised in the gesso since a sketch would be lost under the gold or silver layer. In the 17th century in particular, incised lines were often used to outline folds of clothing where darker colors of the first paint layers would occlude the sketch. This practice became more frequent with the use of thicker and less transparent paints in the 18th and 19th centuries. Both organic pigments (even blood on certain areas of very old icons) and inorganic pigments were used, often with egg yolk as a binding medium. Pigments were often mixtures of three or more, even if only in small amounts (Naumova 1980). Oil paints are sometimes seen on later icons, occasionally as an overpainting. Sankir is a flesh tint made basically of ochre and charcoal with the addition of other pigments such as lead white, glauconite, cinnabar, or azurite. Each icon painter prepared his own mixture, and analyses of sankir have been used to date icons. The subject of an icon was always identified by Old Church Slavonic or Greek orthography, generally in a black paint. 3.4 THE VARNISH LAYERThe olifa, or protective layer of an icon, was traditionally made of linseed oil, although sunflower or poppy seed oil was sometimes used. Occasionally these oils were boiled with a resin or amber, the latter being difficult to dissolve when cleaning an icon. These oils produced a warm, pleasant glow and also protected the paints from the devotional practices of the faithful. 4 THE OKLADMetals were used in conjunction with wooden icons in Russia as early as the 11th and 12th centuries. 4.1 BASMA OKLADSEarly oklads were made of basma nailed to the margins and/or selected areas of the icon. Basma was a handstamped sheet of silver or silvergilt less than half a millimeter in thickness (fig. 3). The basma was often attached to the icon with small silver nails. Some basma oklads covered large areas of the icon, accounting for

4.2 LATER OKLADSIn the 17th century, oklads were often made of one sheet of repousse� and chased metal that repeated the iconography. The metal was excised to expose faces, hands, feet, and other selected details of the icon it covered. Oklads were made of gold, gold-plated silver, solid silver, brass, or copper, silver-plated or plain, often with the addition of enamels, filigree work, pearls, and gemstones. They were sometimes adorned with added halos, crowns, and pendants. Although oklads were intended to beautify and protect icons, they sometimes provided a facade over only half-painted, mass produced icons in the 19th and 20th centuries. Nails used to affix the oklads or their additions often damaged the front of the icon, spalling paint and ground layers. Brass and silver nails caused mechanical damage, and iron nails often deposited rust. 5 PRESERVATION AND PROTECTIONAlthough created solely for liturgical use and personal devotion, icons are also found in museums, private collections, and commercial galleries. The spiritual goals of the church, the material goals of the merchant, and the educational goals 5.1 THE CHURCHExtensive restoration of an icon may be needed for religious use since its prayerful function is dependent upon recognition. In the past, icons were sometimes desecrated by gouging the eyes so that it could not “see.” An icon without eyes was not acceptable for veneration, so before returning to church use, the eyes had to be restored and the icon blessed again. Church restorers are often clergy or lay artists specially blessed for icon restoration. They are expected to understand the iconography, theology, and orthography of the icon. Their goals are to repair, clean, and, if necessary, repaint the icon so that it is recognizable for devotional use. 5.2 THE MERCHANT AND COLLECTORThe goals of the merchant or secular collector include buying and selling for investment, profit, or simply collecting icons as aesthetically pleasing works of art. The preservation objectives of this group reflect their aims and often include restoration. 5.3 THE MUSEUMIdeally, the goal of the museum is education and research as well as the preservation and protection of objects. For the icon, these objectives can be reached through conservation as defined by:

The use of a stereo binocular microscope with fiber optics is urged for all conservators who work with icons. 6 CONCLUSIONStandards of Russian icon conservation often differ markedly among museum conservation laboratories in both the United States and Russia today. Perhaps this is a timely topic for discussion by the Icon Group at the next triennial meeting of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) Committee for Conservation. REFERENCES AND OTHER SOURCESAlhborn, R., and V.Espino3la, eds.1991. Russian copper icons and crosses from the Kunz Collection: Castings of faith. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. Antonova, V. I., and N. E.Mneva. 1963. Katalog drevnerusskoi zhivopisi. 2 vol. Moscow: Isskustvo. Espinola, V. B.1987. The technical examination of Russian icons and oklads. ICOM preprints, 8th Triennial Meeting, International Council of Museums Committee for Conservation, Sydney, Australia.3:1105–1108. Filatov, V. V.1961. Russkoye stankovoya tempernaya zhivopis': Tekhnika i restovratsiya. Moscow: Isskustvo. Lelikova, O. V.1980, 1984, 1987. Director and researcher, Tempera Division, VNIIR, Moscow. Personal communications. Naumova, M. M.1980. Physicist and researcher of old Russian pigments, VNIIR, Moscow, Personal communication. Nikolayeva, T. V.1977. Early Russian painting in the Zagorsk Museum. Moscow: Isskustvo Art Publishers. Ovchinnikov, A. N.1980. Director and researcher, Tempera Division, Grabar Center, Moscow. Personal communication. Riasanovsky, M. V.1969. A history of Russia, 2d ed.New York: Oxford University Press. AUTHOR INFORMATIONVERA BEAVER-BRICKEN ESPINOLA received a B.I.S. in Russian studies from George Mason University and an M.A. in museum studies with a concentration in ethnographic and archeological object conservation from George Washington University. She interned in the Anthropology Conservation Laboratory of the Smithsonian Institution. Fluent in Russian, she received an International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX) grant to study Soviet conservation techniques in Moscow, Novgorod, and Leningrad in 1980. A conservator in private practice in St. Petersburg, Florida, she has worked for museums such as the Smithsonian Institution, Hillwood, and the Timken Gallery, and for churches and private collectors as well as on exhibits, legal, insurance, and environmental problems concerning Russian icons and objects.

Section Index Section Index |