CONSERVATION POLICY AND THE EXHIBITION OF MUSEUM COLLECTIONSNATHAN STOLOW

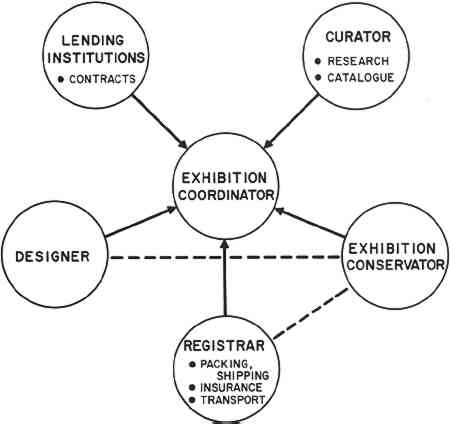

2 EXHIBITION PLANNING AND CONSERVATIONThe conception and planning of an exhibition originates at the top administrative level of the museum. This can have a major impact upon the conservator and his staff. It may be necessary for him to reschedule his work to meet the precise deadlines that exhibitions impose. As regards input at the planning stage the conservator can be called upon to ascertain that the items selected are in good condition. The condition criteria might vary from one conservator to another. There may be a feedback of this information to the exhibition organizers who have the option to choose objects of better physical condition or to arrange for conservation work to be done on the objects found to be fragile. More often it is the policy to keep to the original exhibition list and expect the necessary conservation measures to be taken in time for the opening. In relatively few museums does the conservator, or his equivalent, form part of the decision-making team on the selection of works for a particular exhibition program. Where this is done, the conservator may have useful input too on the physical and environmental

An excellent model of desirable conservation input into exhibition planning was in the organization of the International Exhibition at Expo 67 in Montreal,9 and more recently in the Chinese Archeological Exhibition.14 Naturally, in very large exhibitions the budgets and human resources are generous, allowing for elaborate precautionary procedures. In most museums the works on permanent display, and those in storage, are subject to more or less regular examination by the conservator. He evolves a priority list for treatment based on condition. Usually consultation takes place with the curators concerned. The workload may however be upset by more urgent requirements for assistance in a loan or circulating exhibition program. The deadlines imposed by these situations have to be met, and as a result, the basic conservation of the permanent collection suffers. In this context, too, it is difficult to carry out systematic research over a period of time. The conservator, therefore, spreads himself too thin to meet all the various demands for his services. A particular problem, and a challenging one, is that of the condition report. This report, which is normally written, with accompanying photographs or diagrams, is intended to describe, at a particular time, the actual physical state of the work or object in question. The difficulty is that no two conservators or curators agree precisely on the description of condition. The author recollects vividly remarks made by prominent specialists involved in the organization of certain major international exhibitions that particular objects were in “good” condition. The condition reports included such laconic descriptions. On closer examination by other equally prominent specialists, serious defects in condition were found that could give rise to cracking or losses. The situation is even more confusing in travelling or circulating exhibitions where the diagnosis of condition is successively delegated to the participating museums. It is extremely difficult, often impossible, to establish when a particular damage or condition arose as the individual entries in the report vary in detail and quality. Ideally for such exhibitions there should be one person responsible for assessing conditions at all points. This policy has been implemented in large, very important loan exhibitions where there are accompanying conservators or curators. However, even in this case there have been differences of opinion between the travelling conservator and the local museum conservator over assessment of condition or environmental control factors. A variety of forms have been developed over the years to record condition. Glossaries, or vocabularies have been devised to put more precision into condition reports.16,17 However, improvement can be made by publishing together with such glossaries, illustrative examples. Photographs are very useful to describe a particular condition difficult to record otherwise. There are pitfalls here too in that photographs may be slightly out of focus or taken in such a way as to minimize a particular defect. There clearly must be improvement in condition reporting so that there is common understanding of the terms used. It is not often that the conservator has any input into the handling and packing of exhibitions. In the past the conservator had little responsibility for this, as it is traditionally in the domain of the registrar, foreman of the shops, or the carpenter/shipper. If it is the policy to assign to the conservator total care, then it is difficult to see the logic in not involving the conservator also at the handling and packing phase of the exhibition. Regrettably, much of the packing in museums is still in a primitive stage. While the packaging industry has made much progress (through economic necessity), many museums, even the largest, are still in the “steam age.” The question of maintaining a suitable physical environment for exhibitions during the travel mode is a very difficult one to resolve. This matter has been researched upon, and in a few exhibitions humidity controlled cases have been successfully devised.10,14,15 It is as yet unclear what are the detailed effects of relative humidity and temperature variations, combined with vibration (or shock) upon the structure of museum objects. The basic principle remains to maintain the accustomed environment around the object at all times. It is difficult, however, to ascertain the “proper” environment that should be applied. Efforts have been made to develop loan procedures and criteria that safeguard collections from the conservation point of view.16,18 It would be worthwhile to canvass all major institutions to compare their procedures and criteria. These could very well be at variance with acceptable conservation policy. For example, on many restricted loan lists, panel paintings are not recommended for loan. Yet in such museums the existing environmental conditions are hazardous for hygroscopic objects, such as panel paintings. If consideration is given to the internal variations (microclimate) within “controlled humidity buildings” the hazards to collections can be appreciable. Hygroscopic objects remain dimensionally stable when their moisture contents remain constant. The protection of such objects lies in enclosing them in constant humidity environments until stability is achieved. Presumably a panel painting or hygroscopic sculpture can travel if it is stabilized within its constant humidity envelope. Traditionally, canvas paintings have been considered to be safe to lend, particularly after lining. There may be certain categories of such paintings that should not travel. It is difficult to estimate the effects of vibration and climate variation upon paintings with well-developed crack systems or of large format. A very concerted effort must be made to prepare conservation guidelines and criteria for exhibitions incorporating recent knowledge. Gaps in knowledge can be filled only by investigation and research. |