CONSERVATION POLICY AND THE EXHIBITION OF MUSEUM COLLECTIONSNATHAN STOLOW

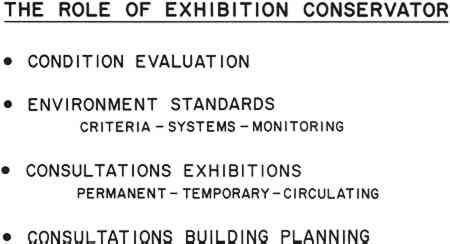

1 INTRODUCTIONThe traditional ordering of museum priorities are acquisition, conservation, and interpretation of collections. In more recent times the second and third priorities have been interchanged as more and more attention is paid in our society to the educational role of museums. There is increasing pressure to bypass (or minimize) conservation and preservation considerations in order to make collections more visible and accessible to the general public. Even storage is no longer sacrosanct. Few museums can retain the policy to keep 80% or more of their collections in storage. Such areas are rapidly becoming secondary exhibition areas. De-accessioning is now employed to remove deadwood from storage and to revitalize the collections. The museum can no longer be likened to an iceberg with only the tip showing. This is too expensive. As government and political authorities focus on the museum they see it increasingly as an educational instrument. It is not surprising to see the shift towards exhibitions and interpretation in the drive towards democratization and decentralization of collections.2 It is well for the conservation profession to accept this tendency and accordingly to adjust its own priorities. Efforts should be made to critically review existing methods and technology employed in the conservation of exhibitions and, where possible, develop newer approaches and standards. In the past decade, a significant proportion of the money and manpower resources available to the conservation profession has been devoted to essentially curatorial research; e.g. analytical studies and the characterization of materials of museum objects. This is, of course, very important, but thought should be given to reassigning our specialists to the present museum priorities. It should not be too difficult to redeploy some of the energy and manpower to focus on the various museological problems generated by a policy of democratization of collections. Thus newer and improved methods must be found to prepare objects for exhibition and travel. At the same time, it is necessary to restudy the question of environmental effects upon such objects and, on the basis of improved knowledge, arrive at more objective guidelines for the care of collections. In this context there must be closer study of such environmental factors as relative humidity, temperature (and their variations), airborne pollutants, light, and vibration. The reopening of this field of study will likely result in the development of the “exhibition conservator,” a professional conservator

A certain amount of research has been carried out in the past on the environmental factors affecting collections. The “state of the art” of this field was described in 1967 at the IIC Congress on Climatology.3 Some significant work has been reported by various authors, more specifically on the subjects of environmental controls and conservation protection during exhibition and travel, and in the employment of the silica gel technique for microclimate control.4–15 There are many unanswered questions and voids in our knowledge of the effect of the environment upon collections. Likewise existing guidelines for control of environmental factors have to be reshaped in the light of new knowledge. For example, what is the rationale for a particular level of relative humidity for collections. What does ultimately happen to objects so exposed. Can panel paintings, under certain conditions, go out on loan? Does relining (or lining) a painting ensure greater safety from the vigors and hazards of travel? Further work has to be done to make more precise and meaningful condition reports. Efforts have been made to establish working vocabularies to describe condition.16,17 Nevertheless, it is not clear what are the actual relationships between environmental stresses and the resultant strains upon museum objects and works of art. There is the intriguing possibility even of delayed action, or fatigue. The whole area of preventative care remains vague. There are no reliable methods to anticipate the onset of a dangerous strain upon an object. What are the “fragility indicators” for paintings, drawings, sculptures, before the first appearance of their respective defects, e.g. cleavage, embrittlement, or corrosion. This paper is intended to stimulate greater interest and effort in the area of exhibition conservation—necessitating the reassignment of existing conservation priorities. |