THE ANCIENT EGYPTIAN COLLECTION AT THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON. PART 1, A REVIEW OF TREATMENTS IN THE FIELD AND THEIR CONSEQUENCESSUSANNE G�NSICKE, PAMELA HATCHFIELD, ABIGAIL HYKIN, MARIE SVOBODA, & C. MEI-AN TSU

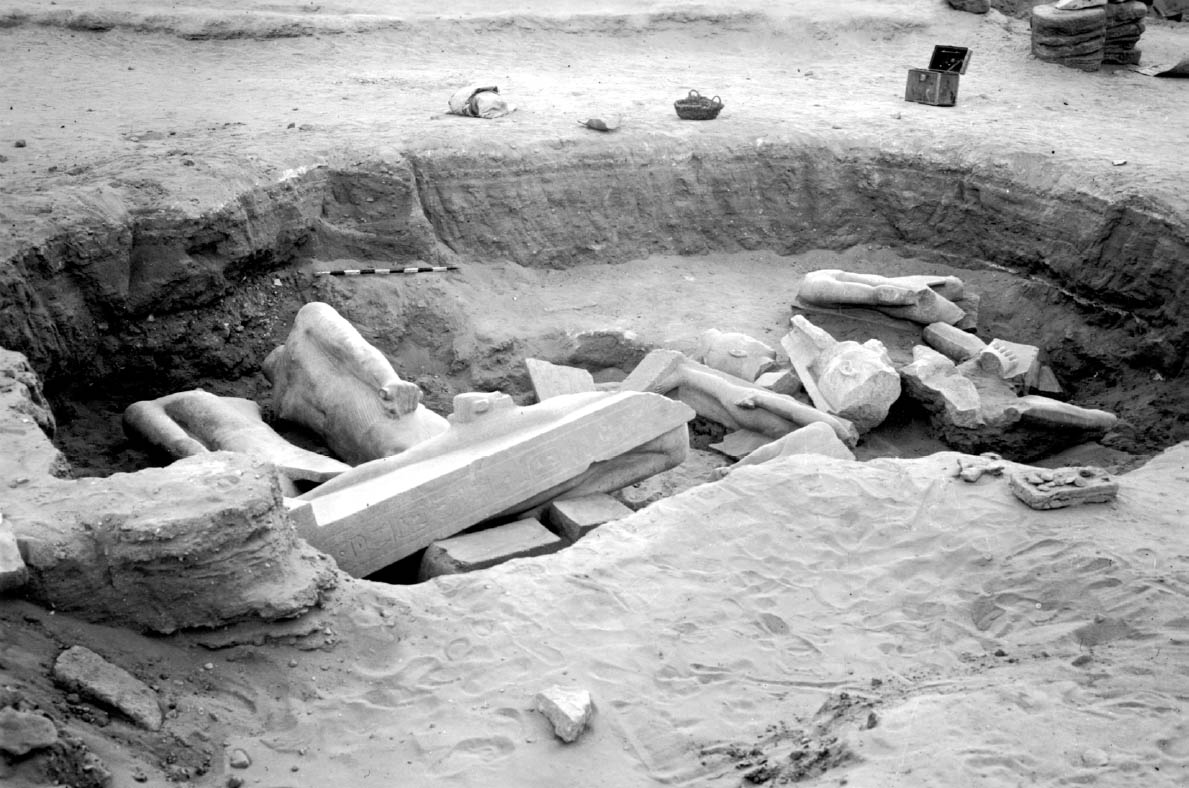

7 STONE7.1 TYPES AND NUMBERS OF OBJECTSNearly 4,000 alabaster vessels primarily from funerary contexts constitute more than half the stone collection. Limestone artifacts, in the form of architectural Stone sculpture has proven to be a significant source of knowledge of ancient Egyptian civilization. Temple and tomb reliefs record dated events, battles, foundation ceremonies, names, titles, and genealogies, all of which are fundamental to re-creating the social and political history of ancient Egypt. The collection also includes masterpieces of Egyptian sculpture, which stand both as valuable historic documents and as testaments to the superb craftsmanship of the ancient Egyptians. 7.2 OVERVIEW OF STONE TREATMENT IN THE FIELDAlthough Reisner's excavation diaries do not record any stone treatments, evidence of cleaning and reconstruction can be seen in excavation photographs (fig. 9). On occasion, treatment practices were discussed in written correspondence between Reisner and other excavation members.

Thick burial encrustations were mechanically removed from sculpture, and in the case of at least one limestone reserve head, dark staining, presumably from iron oxides in the soil, was reduced, possibly by soaking. Vessels were cleaned of their organic contents, most likely according to Lucas's published recommendations:

Cellulose nitrate was primarily used in the field as a consolidant, again most likely as advised by Lucas:“Celluloid is employed in dilute solution in a mixture of equal parts of acetone and amyl acetate, which is sprayed on the object or applied with small soft brush and is especially useful for bone, ivory, painted surfaces and stone” (Lucas 1932, 42). Adhesives commonly used to reconstruct pottery were also used to mend small stone vessels and sculpture. Mucilage and animal proteins were used at Giza and Gebel Barkal, and an opaque white adhesive that contained barium sulfate and was insoluble in acids, water, and organic acids has been identified on stone vessels excavated at Giza from 1911 to 1916. Some large-scale and colossal sculptures from Giza and Gebel Barkal (fig. 10; see also fig. 2) were reconstructed in the field, but pieces of lesser importance appear to have been assembled in Boston. Weightbearing mends were pinned with metal dowels, in some cases brass, and plaster and calcium carbonate mixed with oil and an organic resin were chosen as structural adhesives. It is unclear if stone artifacts were desalinated in the field, and to what extent losses were filled, if at all.

|