CONSTRUCTION HISTORY IN ARCHITECTURAL CONSERVATION: THE EXPOSED AGGREGATE, REINFORCED CONCRETE OF MERIDIAN HILL PARKLORI AUMENT

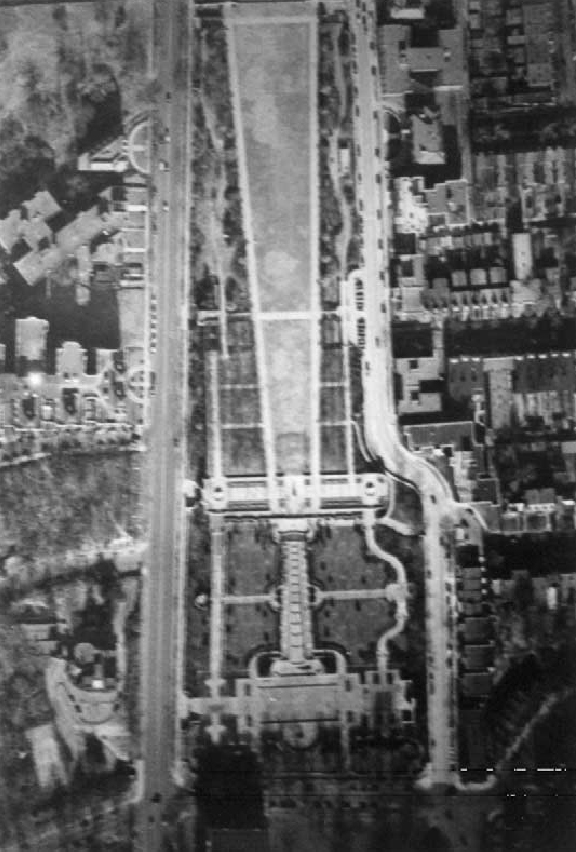

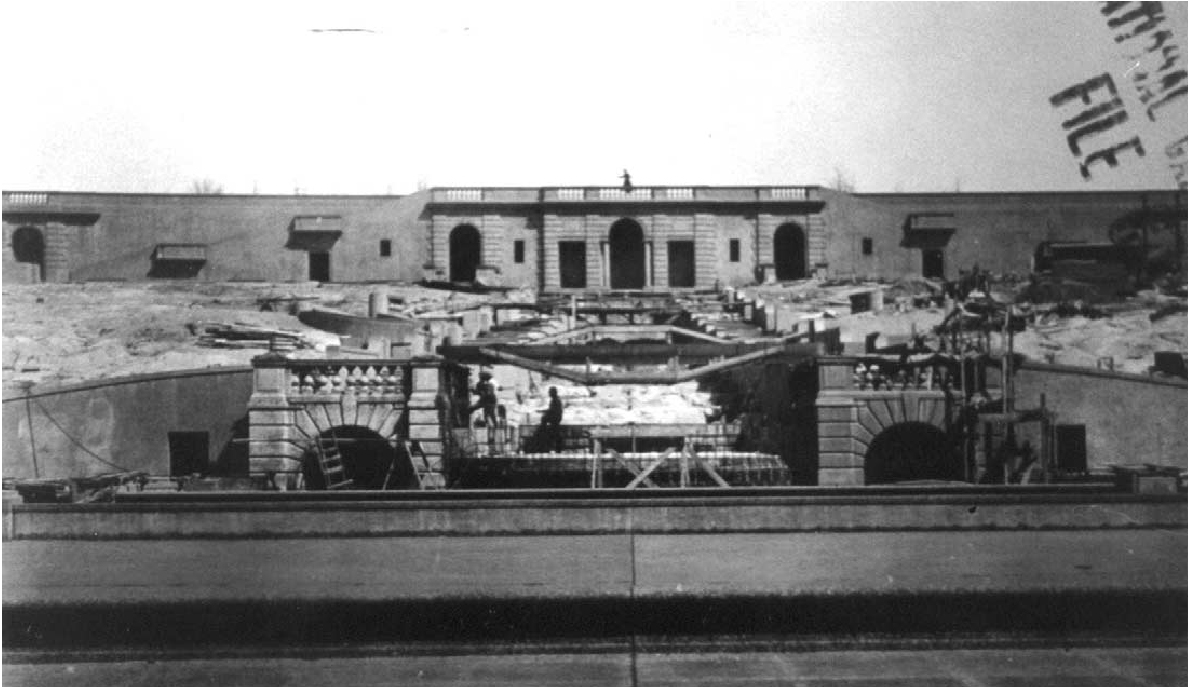

2 MERIDIAN HILL PARK2.1 DESCRIPTIONMeridian Hill Park is located on two city blocks in Washington, D.C., with the long central axis running north-south. The park is bounded on the east by 16th Street, on the west by 15th Street, on the south by W Street, and on the north by Euclid Street (fig. 1). The park area is delimited by perimeter walls with textured panels and heavily rusticated posts. The north end of the park is a level rectangular area planned on axis in the manner of a French formal mall. Two main converging paths lead to the central Grand Terrace. Here, there was once an unobstructed view over the city of Washington. At the Grand Terrace, the topography dramatically drops to the plaza area at the southern end of the park. A series of basins form a cascading water feature, inspired by Italian Renaissance gardens, that leads down the center of the slope, flanked by descending walks on either side (fig. 2). On the lower plaza level, the park opens onto a paved reflecting pool area with a semicircular sitting area to the south, known as an exedra. A low-level balustrade lines the extreme southern end of the park. All the architectural features and decorative elements found at Meridian Hill Park are executed in concrete. Throughout the park, elements as varied as fountains, benches, the massive retaining wall of the Grand Terrace, paving, planting beds, and urns are all constructed of exposed aggregate, reinforced concrete. These features are remarkable for their exposed aggregate finishes, exhibiting a wide array of aggregate sizes, creating subtle textures and colors while defining crisp corners and turning smooth curves (figs. 3–4).

The concrete work at Meridian Hill Park is currently in remarkably good condition, given that it was constructed during a period when concrete was poorly understood and unsound concrete construction practice was widespread. In most areas, the concrete work suffers only from soiling caused by atmospheric pollution or biological growth and, in a few places, damage from vandalism. Relatively little damage has occurred from the corrosion of the reinforcement, which is more than adequately covered in most places, and there is no sign of active, aggressive

2.2 HISTORYIn 1901, the McMillan Commission was formed to develop a plan to improve the park system within the District of Columbia. Meridian Hill was marked as a property suitable for a federal park because of its exceptional views over the capital city. Congress approved an act in 1910 to acquire public land to create Meridian Hill Park as part of the recommendations set forth by the McMillan Commission. In April 1913, George Burnap, architect for the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds, proposed a design for a formal urban space at Meridian Hill Park. Horace Peaslee became the architect in charge of the park when Burnap resigned in 1917. Burnap's main design concept, consisting of a formal park on French and Italian garden precedents, remained constant throughout the 21 years of construction at the park.1

The scale of the park prohibited the use of costly stone masonry. For this reason, concrete was chosen

|