CONSERVATION OF CHINESE SHADOW FIGURES: INVESTIGATIONS INTO THEIR MANUFACTURE, STORAGE, AND TREATMENTLISA KRONTHAL

2 THE ORIGIN OF THE AMNH SHADOW PUPPET COLLECTIONIn 1901, Franz Boas, then a curator in the Department of Anthropology at the AMNH, commissioned the German ethnologist Berthold Laufer to travel to China for field investigation and the collection of artifacts documenting the daily life of the Chinese people. These investigations continued the work of the Jessup North Pacific Expedition, launched in 1897 to research the cultures living along the rim of the North Pacific Ocean, from British Columbia to China and Japan (Stalberg 1983). Laufer was particularly thorough in gathering objects connected with popular performing arts, such as the puppet theater, shadow theater, and local music. He purchased the complete holdings of a 19th-century puppet master of the late Qing (1644-1911) dynasty, including musical instruments, Laufer saw value in studying Chinese shadow theater since he felt it could be the origin of shadow theater around the world. He explained to Boas that many studies published in Germany covered the shadow theater of Turkey, Syria, India, and Indonesia, yet none focused on Chinese shadow theater. Since many of the plots show Buddhist influence, he also considered the material important in understanding the migration of Indian tales throughout East Asia. Unfortunately, Laufer was unable to completely catalog the material he collected before he left for Chicago's Field Museum, which holds another large collection of East City figures. 2.1 DEVELOPMENT OF CHINESE SHADOW THEATERThe first recorded proof of shadow puppetry in China dates to the Song dynasty (960-1279), though references to related activities and events exist prior to that time (Hirsch 1998). A famous story from the Han dynasty (206B. C.-220A. D.) became widely accepted as telling the origin of shadow theater. It describes a time in the life of the Han emperor Wu in which he became despondent over the death of his favorite concubine. To comfort the emperor, a court magician, through the use of shadows and candles, made the image of the concubine appear to the emperor from behind a curtain (Sima 1959). Scholars stress that this unlikely origin for shadow theater became accepted and popularized in the 11th century (Hirsch 1998). The more likely predecessor for shadow theater occurred during the Tang dynasty (618-907), when the art of storytelling was combined with visual components to aid in illustrating the narrative (Hirsch 1998). Buddhist narratives were illustrated with pictures on paper screens or scrolls. Additionally, during the Tang, paper-cuts were pasted on lanterns, screens, and windows with light illuminating them from behind. The images, similar to those created by shadow figures, lead many people to see them as inspiration for shadow puppets. In fact, the earliest Chinese shadow puppets known from the Song dynasty were made of paper. More concrete evidence of the existence of shadow theater occurs in the Song dynasty. The Mengliang Lu (A Record of the Millet Dream) was written about the southern Song capital and gives a descriptive account of shadow theater:

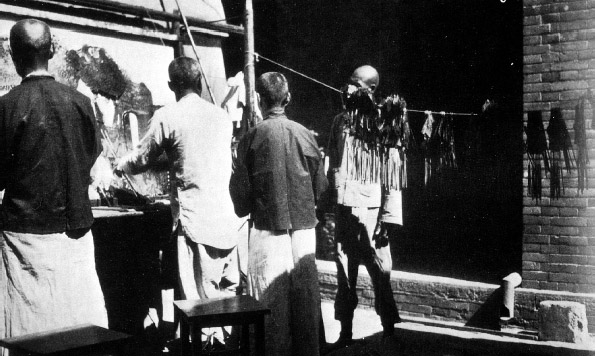

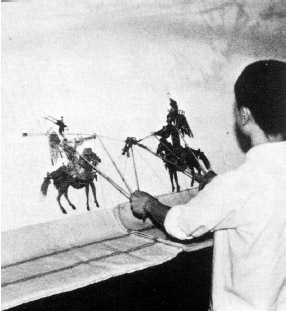

Beginning in the 11th century, the shadow theater tales of battles and myths were performed by itinerant entertainers throughout the countryside and were no longer performed within walled cities or towns. This development was due to numerous decrees by a series of rulers prohibiting ritual and drama. By the early Ming dynasty (1368-1644), a general revival of shadow puppetry took place, and the performances again became part of the culture within the cities and in the countryside (Hirsch 1998). The artistry of the figures had assumed an important and respected role in theater, and several distinct schools of shadow theater emerged. The Luanzhou School in Beijing gained fame and royal sponsorship during the late Ming. Under the Qing dynasty, two branches within this school developed and were known as East City (Beijing) and West City types. 2.2 EAST CITY SHADOW THEATERThe Eastern school, which is the focus of the AMNH collection, is considered by many to be the most refined of the Chinese shadow puppet schools (Erda 1979; Stalberg 1983). It employs very skilled, detailed carving techniques and the thinnest and most translucent skins. The puppets are carved into shapes of human figures, animals, or scenery and are designed to be manipulated by rods in front of a lamp

The theater incorporates elaborate props, furniture, and scenery, creating spectacular and complex compositions on the screen. Dragons, monsters, and flying immortals as well as fires, battles, and bloody deaths are vividly depicted. The advantage of shadow theater is that myths and legends involving fantastic transformations can be performed with great ease and depicted more fully than in other performing arts such as opera, marionette theater, or hand puppetry. The illusion of light and colored shadow allows for flight, decapitation, spurting blood, sudden

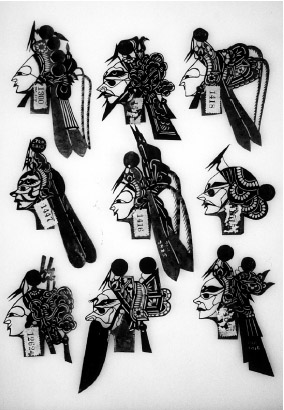

2.3 INFLUENCE BY CHINESE OPERAAs in regional opera, the puppet masters used painted faces, masks, distinctive movements, and elaborate costume design to identify and distinguish the characters. The masks, face painting, and costumes allowed the viewer, familiar with the meanings of each color and form, to recognize the personalities of the characters in a drama (fig. 4, 5). As in the opera, the characters in shadow theater are divided into four major groups: the Chou (male or female comic actors), the Jing (male military characters), the Sheng (scholars or officials), and the Dan (women characters who can be military, educated, or servants, old or young). Immortals, supernaturals, or demons can take any of these roles (Broman 1981). Painted faces and headdresses symbolize the personality traits or rank of the different characters. For example, a fierce and powerful general may wear a red and black mask, the red designating strength and the black loyalty. A female gossip might have an ornate hat and a pockmarked face.

The style and methods used for cutting and carving the skin also help to distinguish personalities or identities. The faces of noble gentlemen and women are usually completely cut away, leaving graceful outlines of eyes, nose, lips, and forehead (see fig. 5), while those of the comic actors, warriors, mythological, and hell figures are most often left solid or

|