CONSERVATION OF CHINESE SHADOW FIGURES: INVESTIGATIONS INTO THEIR MANUFACTURE, STORAGE, AND TREATMENTLISA KRONTHAL

ABSTRACT—Chinese shadow figures of the Beijing, East City, type were cut from translucent skin, painted with dyes, and coated with tung oil. The history of the American Museum of Natural History's collection of Chinese shadow figures and details concerning the materials and techniques used in their manufacture are described in this article. Also covered is the shadow theater's relationship to Chinese opera in symbolism, color, and form. The tung oil coating in this collection, as in most, has remained tacky, resulting in extensive damage due to adhesion of elements to themselves and to storage materials. Other common damage includes tears and distortions of the skin and detached elements. A survey of the collection is given, and research into appropriate materials and techniques for new storage and treatment is described, as well as investigations into silicone-coated Mylar as a long-term storage material. For tear repairs, a range of intestinal lining materials including goldbeater's skin, reconstituted collagen, and natural skin condoms, in combination with adhesives including gelatin, Beva 371, Paraloid F-10, and polyvinyl acetate resins, is presented. TITRE—La conservation des marionnettes du th��tre d'ombres chinoises: recherche sur leur fabrication, mise en r�serve et traitement. R�SUM�— Les marionnettes du th��tre d'ombres chinoises typiques de la partie est de la ville de Beijing, ont �t� cr��es de peau animale translucide color�e avec des teintures et enduite d'huile de bois de Chine. Cet article d�crit l'histoire de la collection de marionnettes du th��tre d'ombres chinoises appartenant au American Museum of Natural History (mus�e am�ricain d'histoire naturelle), ainsi que leurs mat�riaux et techniques de fabrication. On y discute en outre des rapports entre le th��tre d'ombres et l'op�ra chinois, quant aux aspects de symbolisme et d'utilisation des couleurs et des formes. L'huile de bois de Chine recouvrant les marionnettes de cette collection est demeur�e visqueuse, comme dans bien des cas pour ce genre d'objets. Il en r�sulte de nombreux dommages dus � l'adh�rence des �l�ments de marionnette entre eux et aussi aux mat�riaux utilis�s pour la mise en r�serve. Les d�chirures et les d�formations de la peau animale sont fr�quentes sur les marionnettes, ainsi que les bris donnant lieu � des pi�ces compl�tement d�tach�es. Cet article pr�sente les r�sultats de l'�tude de cette collection et des recherches pour d�terminer les mat�riaux et techniques appropri�s pour le traitement et la mise en r�serve � long terme, incluant entre autres l'utilisation de la pellicule stratifi�e Mylar-silicone. Pour la r�paration des d�chirures, un vari�t� des membranes d'origine intestinale a fait l'objet d'essais, dont la baudruche, le collag�ne reconstitu� et les condoms en peau naturelle, en combinaison avec des adh�sifs tels la g�latine, le BEVA 371, le Paraloid F-10 et les r�sines � base d'ac�tate de polyvinyl. TITULO—Conservaci�n de figuras de sombras chinas: investigaci�n acerca de su manufactura, almacenamiento y tratamiento. RESUMEN—Las figuras de sombras chinas del tipo de Beijing, Ciudad Este, eran cortadas a partir de pieles transl�cidas, pintadas con tintes, y recubiertas con aceite de tung. En este art�culo se describen la historia de la colecci�n de figuras de sombras chinas del Museo Americano de Historia Natural, y los detalles concernientes a los materiales y t�cnicas usados en su manufactura. Tambi�n se tratan las relaciones de simbolismo, color y forma, que hay entre el teatro de sombras y la �pera china. En esta colecci�n, al igual que en la mayor�a de otras colecciones, el recubrimiento de aceite de tung ha permanecido pegajoso, resultando en da�o extensivo, debido a la adherencia de los elementos entre s� y a los materiales de almacenamiento. Otros da�os comunes incluyen: roturas y distorsiones de la piel, y elementos desprendidos. Se presenta un inventario de la colecci�n, y se describe una investigaci�n sobre los materiales y t�cnicas apropiados para el nuevo almacenaje, as� como tambi�n investigaciones sobre el Mylar recubierto de silicona como material para almacenamiento a largo plazo. Se presenta un rango de materiales derivados de tripa intestinal empleados en la reparaci�n de roturas, incluyendo piel de batidores

1 INTRODUCTIONAsian shadow theater is a dramatic art form that has survived centuries to tell historic tales and myths that remain relevant in contemporary cultures and societies. A comprehensive collection of 19th-century Beijing, East City, type shadow figures was acquired for the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) by the renowned sinologist and ethnographer Berthold Laufer (187?–1934). The small skin figures were carved and painted to project vividly colored and detailed images upon the screen. Articulated limbs, detachable heads, and magnificent scenery enhance the fantastic stories and tales (fig. 1). There are similar collections of East City type shadow figures in the United States and Europe.1 The puppets within these collections have comparable condition issues due to a traditionally applied coating that remains sticky over time and to the inherent fragility of the finely carved skin, which is prone to tears and losses. The AMNH archives contain extensive correspondence between the keepers of these collections, primarily concerning the problematic coating. These documents show a clear attempt to resolve condition issues using a variety of materials and techniques, including applying Scotch tape for tear repair, sandwiching puppets between sheets of waxed paper, and completely removing the coating. Once considered acceptable, these methods of treatment are no longer used, as they often left individual puppets as well as whole collections irreversibly damaged. Although the coating is problematic, its historic importance makes its removal unacceptable. Its preservation was considered paramount in this project, and treatment procedures that were compatible with it needed development. Additionally, a storage system that would resolve the problems encountered in the past would also need to be designed. 2 THE ORIGIN OF THE AMNH SHADOW PUPPET COLLECTIONIn 1901, Franz Boas, then a curator in the Department of Anthropology at the AMNH, commissioned the German ethnologist Berthold Laufer to travel to China for field investigation and the collection of artifacts documenting the daily life of the Chinese people. These investigations continued the work of the Jessup North Pacific Expedition, launched in 1897 to research the cultures living along the rim of the North Pacific Ocean, from British Columbia to China and Japan (Stalberg 1983). Laufer was particularly thorough in gathering objects connected with popular performing arts, such as the puppet theater, shadow theater, and local music. He purchased the complete holdings of a 19th-century puppet master of the late Qing (1644-1911) dynasty, including musical instruments, Laufer saw value in studying Chinese shadow theater since he felt it could be the origin of shadow theater around the world. He explained to Boas that many studies published in Germany covered the shadow theater of Turkey, Syria, India, and Indonesia, yet none focused on Chinese shadow theater. Since many of the plots show Buddhist influence, he also considered the material important in understanding the migration of Indian tales throughout East Asia. Unfortunately, Laufer was unable to completely catalog the material he collected before he left for Chicago's Field Museum, which holds another large collection of East City figures. 2.1 DEVELOPMENT OF CHINESE SHADOW THEATERThe first recorded proof of shadow puppetry in China dates to the Song dynasty (960-1279), though references to related activities and events exist prior to that time (Hirsch 1998). A famous story from the Han dynasty (206B. C.-220A. D.) became widely accepted as telling the origin of shadow theater. It describes a time in the life of the Han emperor Wu in which he became despondent over the death of his favorite concubine. To comfort the emperor, a court magician, through the use of shadows and candles, made the image of the concubine appear to the emperor from behind a curtain (Sima 1959). Scholars stress that this unlikely origin for shadow theater became accepted and popularized in the 11th century (Hirsch 1998). The more likely predecessor for shadow theater occurred during the Tang dynasty (618-907), when the art of storytelling was combined with visual components to aid in illustrating the narrative (Hirsch 1998). Buddhist narratives were illustrated with pictures on paper screens or scrolls. Additionally, during the Tang, paper-cuts were pasted on lanterns, screens, and windows with light illuminating them from behind. The images, similar to those created by shadow figures, lead many people to see them as inspiration for shadow puppets. In fact, the earliest Chinese shadow puppets known from the Song dynasty were made of paper. More concrete evidence of the existence of shadow theater occurs in the Song dynasty. The Mengliang Lu (A Record of the Millet Dream) was written about the southern Song capital and gives a descriptive account of shadow theater:

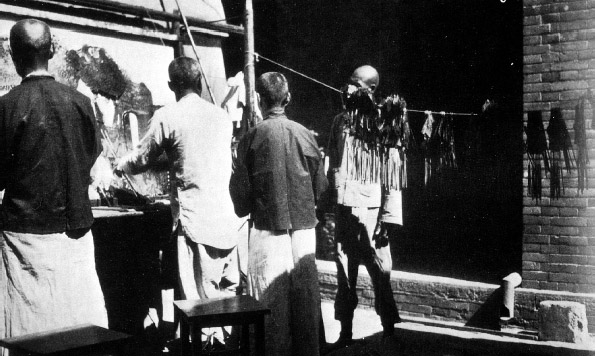

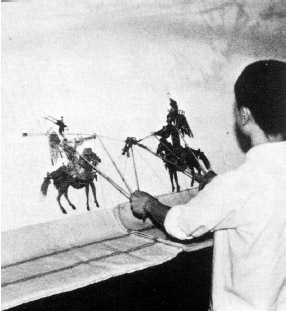

Beginning in the 11th century, the shadow theater tales of battles and myths were performed by itinerant entertainers throughout the countryside and were no longer performed within walled cities or towns. This development was due to numerous decrees by a series of rulers prohibiting ritual and drama. By the early Ming dynasty (1368-1644), a general revival of shadow puppetry took place, and the performances again became part of the culture within the cities and in the countryside (Hirsch 1998). The artistry of the figures had assumed an important and respected role in theater, and several distinct schools of shadow theater emerged. The Luanzhou School in Beijing gained fame and royal sponsorship during the late Ming. Under the Qing dynasty, two branches within this school developed and were known as East City (Beijing) and West City types. 2.2 EAST CITY SHADOW THEATERThe Eastern school, which is the focus of the AMNH collection, is considered by many to be the most refined of the Chinese shadow puppet schools (Erda 1979; Stalberg 1983). It employs very skilled, detailed carving techniques and the thinnest and most translucent skins. The puppets are carved into shapes of human figures, animals, or scenery and are designed to be manipulated by rods in front of a lamp

The theater incorporates elaborate props, furniture, and scenery, creating spectacular and complex compositions on the screen. Dragons, monsters, and flying immortals as well as fires, battles, and bloody deaths are vividly depicted. The advantage of shadow theater is that myths and legends involving fantastic transformations can be performed with great ease and depicted more fully than in other performing arts such as opera, marionette theater, or hand puppetry. The illusion of light and colored shadow allows for flight, decapitation, spurting blood, sudden

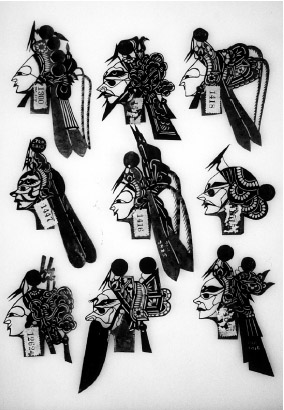

2.3 INFLUENCE BY CHINESE OPERAAs in regional opera, the puppet masters used painted faces, masks, distinctive movements, and elaborate costume design to identify and distinguish the characters. The masks, face painting, and costumes allowed the viewer, familiar with the meanings of each color and form, to recognize the personalities of the characters in a drama (fig. 4, 5). As in the opera, the characters in shadow theater are divided into four major groups: the Chou (male or female comic actors), the Jing (male military characters), the Sheng (scholars or officials), and the Dan (women characters who can be military, educated, or servants, old or young). Immortals, supernaturals, or demons can take any of these roles (Broman 1981). Painted faces and headdresses symbolize the personality traits or rank of the different characters. For example, a fierce and powerful general may wear a red and black mask, the red designating strength and the black loyalty. A female gossip might have an ornate hat and a pockmarked face.

The style and methods used for cutting and carving the skin also help to distinguish personalities or identities. The faces of noble gentlemen and women are usually completely cut away, leaving graceful outlines of eyes, nose, lips, and forehead (see fig. 5), while those of the comic actors, warriors, mythological, and hell figures are most often left solid or

3 TECHNOLOGY: MATERIALS AND MANUFACTUREThe construction of a shadow figure of the East City type begins with soaking a hide in water and then stretching it on a frame. The wet skin, traditionally donkey, is rubbed and scraped, first with a stone, then with bamboo, until it is thinned to translucency. Often, the hide of a young animal or a hide that has been split or skived is used for parts of the figures that require greater translucency. When thicker skins were needed, sheep or cow was used (Erda 1979; Jilin 1988). The outline of the figure is traced or drawn freehand onto the skin, usually by incising, and is cut out using specialized chisels and knives (fig. 6). Most of the puppets depict human figures and are composed of 11 parts. For less important figures, the legs, torso, and even head may be cut from one solid piece of hide. These characters are not required to express multiple personalities and therefore do not need to make the range of movements obtained with the more complex articulated puppets. As mentioned, different parts of the puppet body are made from different sections of the hide. Traditionally, the skin from the belly of the donkey is employed for faces and upper body parts, while thicker sections are more appropriate for the feet, legs, and torso. The thinner skins of the faces transmit more light, creating a sense of illumination, while the weight and rigidity of the thicker skins in the lower body keep the puppet balanced and stable. Often tiny lead plates are attached to the bottom of the pant legs to obtain greater balance and to allow the legs to swing back and forth, simulating a walking stride. The puppet maker cuts joints between the legs, arms, and torso into shapes resembling wheels with spokes. These radial cuts prevent a large dark spot from appearing on the screen where parts inevitably overlap, creating two layers for the light to penetrate. This technique can be seen in the puppet shown in figure 1 at the elbow junctures, at the tops of the legs, and through the center of the figure. Silk, cotton string, or flaps of rawhide hold the parts together, and occasionally metal wire is used to reinforce separate elements. The heads are not attached permanently. Instead, they fit into a collar of parchment, allowing the character to change costume or persona in the course of a performance. Often many heads are needed to show the changing status and emotions of a single character in the course of a play. This construction also allows decapitation, a frequent mode of execution, to be convincingly portrayed. The puppeteer attached iron alloy wires with bamboo handles to the figures for manipulation. Traditionally, the skin was painted on both sides with vegetable dyes. Later, synthetic dyes and paints were used. An application of oil, usually tung oil, was applied in order to saturate the colors, resulting in a more vivid projection as well as greater transparency. Periodically, as part of the regular maintenance of his collection, the puppeteer reapplied the coating. 3.1 CONDITION: INHERENT INSTABILITIESStructural instabilities throughout the collection are mostly related to the manufacture of the puppets, specifically their thinness and intricately cut designs. Common damage resulting from this inherent disadvantage include tearing of the skin, distortion, and detached elements. It was common for the puppet master to manufacture his own figures and to regularly restore damaged figures. Therefore, before any treatment is accomplished, a clear distinction must be made between ethnographic and modern interventions. Ethnographic repairs in the Laufer collection include sewing, pinning, and patching with skin. These repairs have historic importance and should be preserved if possible. Modern attempts at restoration include applying transparent, pressure-sensitive tape to tears and using paper clips to connect detached elements. In most cases, it is appropriate to remove and redo these repairs using more appropriate materials or techniques. 3.2 THE TUNG OIL COATINGThe tung oil coating is the main culprit in creating condition and preservation issues in many shadow puppet collections. In the AMNH collection, old storage facilities in non-climate-controlled environments aggravated these issues. Puppets piled into shallow trays were found stuck to adjacent puppets, to storage materials like brown Kraft paper, or to plastic bag enclosures. Correspondence with other institutions and private collectors indicates that this sticking problem was widespread.3 A 1974 letter to AMNH restorers from a restorer working in a large American museum reads:

The AMNH response to this inquiry suggested either complete removal of the coating using methyl ethyl ketone solvent (MEK) or “if one wanted to preserve the coating then application of Butcher's wax would act to prevent sticking.” The collection Another letter in the AMNH archives describes a different approach. In this case, removal of the coating would cause irreparable changes. Instead, paraffin was applied directly to the surfaces in an attempt to reduce the sticking. When conservators were unsatisfied with the results, the surfaces were rubbed with Vaseline (AMNH 1974). These approaches to the problematic coating either attempted to cover it with another material or to remove it altogether. At the AMNH, we consider both of these options unacceptable. Instead, a lessintrusive treatment involving upgrading storage conditions and developing treatment procedures compatible with these inherently fragile and sticky artifacts needed to be developed. 3.3 TUNG OIL: CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICSAn investigation into tung oil and its drying properties offered some help in understanding the troublesome surface treatment. Most references concerning Beijing shadow figures describe tung oil as the primary coating material. Several oil samples were removed from puppets in the collection. These represented the range of oil types found on the puppets as distinguished by their surface characteristics. All samples were positively identified as tung oil by using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS). George Wheeler accomplished the analysis at the Metropolitan Museum of Art Conservation Laboratory. Tung oil, also known as Chinese wood oil, is obtained from the seeds of the fruit of Aleurites fordii, a tree that has grown in China for centuries (Gettens and Stout 1942). The native method for separating the oil involves roasting the seeds over a flame and grinding them with stones or wooden presses. A coldpressed version of the oil called “white tung oil” is light in color and is mostly exported. The hot pressed oil has a very dark color and is called “black tung oil.” Tung oil contains a large proportion (75-85%) of eleostearic acid, a stereo-isomeride of linoleic acid, which is found in linseed oil. These acids contain two unsaturated double bonds, a property that gives an oil its drying property. However, under normal temperature and humidity conditions, tung oil takes approximately 30 days for a full gain in weight or for drying to be complete, distinguishing it as a slow-drying oil. In fact, tung oil is not recommended as an artist's material since it requires extensive processing to dry to a satisfactory level (Gettens and Stout 1942). Under humid conditions the oil will dry more rapidly, with a resulting film that is wrinkled, cracked, or reticulated. This drying-rate increase in moist air is not “drying” in the usual sense through oxidation and polymerization. Instead it is thought that the oil is coagulating from the high moisture exposure and is therefore thicker and more viscous but not necessarily drier (Gettens and Stout 1942). The reticulated surface texture of the coatings on the puppets is common and could have resulted from application and “drying” in a humid environment. 4 REHOUSING AND SILICONE MYLARSince the oil has ethnographic significance and cannot be altered or removed, choosing appropriate and compatible storage materials for rehousing is a priority. Several attempts at creating safe housing for the collection were undertaken in the past. In spite of good intentions, these campaigns have complicated storage and condition issues. A variety of materials were used as interleaves, including silicone release paper, acid-free tissue, brown Kraft paper, Mylar, and plastic. The figures stuck to all of these surfaces. Requirements for the new storage environment included controlled temperature and humidity conditions as well as storage on a surface that is nonstick, nonreactive, and nontextured. We considered vertical storage, Teflon surfaces, and silicone-coated Mylar surfaces. Vertical storage was impractical due to space considerations. The thought was that the puppets would hang from a horizontal support so that none of their surfaces touched any storage material. An additional concern with this During this investigation, which began in 1994, the Teflon we were considering was in a thick sheet or tile form, and the cost of this product was too high. At the time, we were not aware of the possibilities of using Teflon films. Teflon tape (plumber's tape) was considered but later eliminated as an option due to the narrow strip form in which it was supplied. Since then, we have been made aware of the use of such film supplied in a wider form (Odegaard et al. 1997). The film can be purchased in widths up to 12 in. and is a viable option for long-term storage of artifacts with tacky surfaces. Initial investigation into the material indicates that its release level is not as high as necessary for the high tack of the puppets. At the time of the shadow puppet rehousing project, our focus went to silicone-coated Mylar as a practical choice. During our investigation into this material, we realized that the silicone coating on the Mylar on hand in the conservation laboratory was not permanently “adhered” to its substrate and was readily removed by a range of solvents. For long-term storage, such qualities were unacceptable since the eventual loss of the nonstick properties of this material when in contact with the soft oil seemed too risky. Further research into the range of technologies involved in the manufacture of the product led to the discovery of several interesting facts. Many companies purchase the raw Mylar, using Dupont Mylar A or D, and apply the silicone coatings using several polymerization techniques, the major ones involving UV or heat-curing technologies. Conflicting opinions from the suppliers about the effect of these processes on the final physical qualities of the coating were common. Most claimed there are varying levels of transfer of the coating to whatever material is laid upon it, the UVcured coatings transferring the least and the heatcured coatings having a higher possibility of transfer. Requirements for the storage surface for the shadow puppets included a film with a low transfer potential and medium or high release levels. A coating company named Douglas Hanson uses a UV activation polymerization technique that results in a product that meets these requirements, and both Conservators' Products and Talas distribute this product. Rehousing the collection involved preparation of each shelf by lining it first with acid-free corrugated board and then with the Douglas Hanson siliconecoated Mylar. Puppets were laid onto the Mylar surfaces and pinned in position through preexisting holes in the carvings with map pins that had been coated with an isolating layer of Paraloid B-72. The pins were used to keep the puppets from sliding out of place when trays were pulled out of their cabinets. This event was common on the slick Mylar surface. 5 TREATMENTDuring the rehousing, a survey of the entire collection was conducted in order to prioritize treatment. The survey results were entered into a database created specifically for the collection. It was found that more than 300 of the approximately 1,500 puppets were considered first priority, and most were in need of treatment. These puppets often required the removal of old storage materials stuck in the coating, mending of tears within the skin, or reattaching separated elements. Solubility tests on the coating revealed that it was soluble, in varying degrees, in a wide range of solvents. Acetone and ethanol solubilized the coating readily, toluene, petroleum benzine, and xylene moderately, and Stoddard solvent minimally. In most cases, the coating had saturated the storage material, and separation would inevitably involve some loss of coating. The goal in removal of the storage materials from the puppet surfaces was to retain as much of the original coating as possible along with its original, reticulated texture. By wetting the papers with Stoddard solvent, a scalpel could be inserted at the interface of the coating and the paper, and, in most cases, the paper could be removed with minimal loss of oil. The Stoddard solvent appeared to function mostly as a lubricant enabling separation of the layers while retaining the original surface texture of the coating. 5.1 MENDING TEARS IN TRANSLUCENT SKIN: LINING OPTIONSThe goals in mending were to find a combination of materials that was compatible with the skin and oiled substrate and that would maintain the transparency

The collagens were given primary consideration due to their visual and chemical compatibility with the skin substrate. Several concerns developed when considering the use of the sausage casings in this treatment. The preparation of the collagen in manufacturing a casing involves reducing bits of animal skin (generally cowhide) in hydrochloric acid, spinextruding the gelled product, bathing it in aluminum sulfate, buffering it, and adding plasticizers, consolidants, and tanning agents (Morrison 1986). These steps, especially the acid preparation, reduce the length of the collagen fibers, resulting in a product that has a very short shelf life and quickly becomes brittle upon removal from the package (Woods 1997). Requirements for a stable, flexible mend led to the elimination of this product as an option. The natural skin condoms were more promising. The intestinal material used in their manufacture comes from the cecum of the large intestine of sheep or lamb. The processes involved in its preparation include trimming and defatting of the skin, soaking it in salt solutions, addition of surfactants, light tanning, and coating with a lubricant that can be removed with acetone or ethanol. There is no acid preparation involved, as maintenance of strength and endurance are crucial requirements for such products. Unfortunately, for use on the puppets, the final product is too thick and does not lead to visually acceptable results, but it may be useful for other types of mending that require more thickness or strength.

It was concluded that goldbeater's skin resulted in successful mends that were strong, unobtrusive, and transparent. Talas supplies sheep appendix goldbeater's skin, but other suppliers will carry skin made from the cecum of intestinal material. Before use, it must be degreased using acetone and its surfaces lightly abraded with pumice to reduce unevenness. The final product is much thinner and more transparent than any of the other products considered. It can be toned with dyes in order to achieve desired colors while maintaining translucency. Orasol dyes in ethanol were used for this purpose. 5.2 ADHESIVE OPTIONSSeveral adhesives in both film and solvent form were tested in conjunction with the goldbeater's skin lining. Requirements of the adhesive include compatibility with the skin, the coating, and the lining material, as well as long-term stability, transparency, and flexibility. Included in these categories were gelatin, Beva 371, polyvinyl acetate resins, and Paraloid F-10. After a number of trials, it was found The long-term stability of adhesives in a low pH environment, like that created by skin or oil, is an area that needs investigation and research. Most of the research to date tends to focus on how adhesives age in neutral pH environments. Experiments currently are being developed in the conservation laboratories at the AMNH that will attempt to determine the aging properties of commonly used adhesives for skin repair. 5.3 THE MENDING PROCESSPrior to applying mending materials, the oil in the mend locations was reduced. Since the oil penetrates into the porous skin, it is impossible to remove completely. If necessary, the area to be mended can be relaxed into position using controlled humidification techniques, then dried under pressure. (Humidification techniques involve layering Goretex, slightly dampened blotter, and plastic over the distorted area. Generally, the skin reacts to humidification readily, and this step needs to be closely monitored to avoid wetting the skin.) Often, both sides of a tear will need the reinforcement offered by the mending materials. The final mended tear is strong, clear, and flexible (fig. 7, 8). 6 CONCLUSIONIn the 20th century, especially between 1920 and 1970, shadow puppetry in China went through dramatic transformations. Plastic sheets replaced the fine skin puppets, and synthetic colors supplanted the natural dyes. Combined with cruder cutting techniques, the effect was cheap and represented a sad departure from the tradition of the elegant, older shadow puppets. Communist ideology became a dominant theme for shadow troupes so that content within the dramas changed as well. After the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) ended, village troupes began to perform traditional dramas again, using puppets that were 100 to 200 years old (Berliner 1986). Even with this rebirth, the popularity of this theater has suffered in the shadow of modern film and performance. An interview with an old shadow puppeteer in Beijing in the 1930s concerning the state of the theater reveals his beliefs concerning the future of shadow theater in China:

The current state of shadow theater has been presented to reinforce the importance of preserving these items and was a determining factor in prioritizing the AMNH collection for rehousing and treatment. The rehousing, survey, and treatment of the AMNH Chinese shadow puppet collection demanded resolution of conservation issues that, while focusing on ethnographic artifacts, can be applied to a wider variety of collections. Preservation of the original function and composition of the puppets was considered paramount, and treatments were developed to accommodate the challenging materials that compose them. These treatments were customized for a large-scale collection that is often the focus of research and exhibition. In pursuing an acceptable approach to the needs of this collection, the author was granted the opportunity to research the history and technology of shadow puppetry in China. Simply understanding the importance of color and form within the figures was a determining factor in their subsequent treatment. Investigations into past treatments created focused awareness on the detrimental results that ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSI thank Samantha Alderson and Judith Levinson of the Conservation Lab at the American Museum of Natural History for their continued support and suggestions concerning this project. Thanks to George Wheeler at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for his analysis of the oil samples and to Tracy Power at the San Francisco Asian Art Museum for her input on the history of the treatment of similar collections. Special thanks to Mary Hirsch at the Seattle Art Museum for her editing expertise and her contagious enthusiasm for Chinese shadow theater. NOTES1. Other large collections of the East City type puppets are in the Museum of Folk Art, Hamburg; the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco; the Volkekunde Museum, Leiden, Netherlands; the Ethnographic Museum of Sweden, Stockholm; and the Lederschaft Museum, Offenbach, Germany. 2. In her master's thesis, Mary Hirsch gives a detailed, academic survey of the history of Chinese shadow theater, referring to historic texts and play scripts. Additionally, Hirsch presents detailed distinctions between the different schools of shadow puppetry. 3. Caretakers of similar collections who have noted sticking problems include those at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco and the Museum of Folk Art in Hamburg, as well as various private collectors. REFERENCESAMNH. 1974. Shadow puppets: Conservation. Anthropology Department Archives. American Museum of Natural History, New York. Berliner, N. Z.1986. Chinese folk art: The small skills of carving insects. Boston: Little Brown. Broman, S.1981. Chinese shadow theater. Monograph series 15. Stockholm: Ethnographical Museum of Sweden. Erda, B.1979. Shadow images of Asia: A selection of shadow puppets from the American Museum of Natural History. New York: Katonah Gallery. Gettens, R. J., and G. L.Stout.1942. Painting materials: A short encyclopedia. New York: Dover. Hirsch, M.1998. Chinese shadow theater playscripts: Two translations. M. A. thesis, University of Washington, Seattle. Jilin, L.1988. Chinese shadow puppet plays. Beijing: Morning Glory. Morrison, L.1986. The conservation of seal gut parkas. Conservator10:17–24. Odegaard, N., M.Crawford, and W.Zimmt. 1997. The use of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) film for storage supports. Journal of the American Museum of Natural History36(3):249–51. Sima, Q.1959. Shi ji (Records of the historian). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. Stalberg, R.1983. Berthold Laufer's China campaign. Natural History Magazine92(2):34–39. Wimsatt, G.1936. Chinese shadow shows. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Woods, C.1997. Repairing parchment with collagen. April 16, 1997. Conservation distribution list archive: http://palimpsest.stanford.edu/byform/mailinglists/cdl/1997/0513.html FURTHER READING

Benton, P.1972. Chinese shadow plays. New York: Asia Society. Dolby, W.1961. The origins of Chinese puppetry. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies41(1):97–120. Hsu, T.1984. The Chinese conception of theater. Seattle: University of Washington Press. Laufer, B.1923. Oriental theatricals. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History. Lu, S.1968. Face painting in Chinese opera. New York: DBS. March, B.1938. Chinese shadow figure plays and their making. Handbook 11. Detroit: Puppetry Imports. Stalberg, R.1984. China's puppets. San Francisco: China Book. UCLA Museum of Cultural History. 1963. Asian puppets: Wall of the world. Los Angeles: University of California. SOURCES OF MATERIALSParaloid B-72100% solids, ethyl methacrylate copolymer, manufactured by Rohm and Haas, Philadelphia, Pa. 19105 Conservation Support Systems P.O. Box 91746 Santa Barbara, Calif. 93190-1746 Paraloid F-1040% solids in mineral thinner/Amsco fat solvent ratio 9:1. Solids composed of butyl methacrylate polymer. Conservator's Emporium 100 Standing Rock Circle Reno, Nev. 89511 Beva 371 Solution40% solids in a solution of toluene and naphtha. Solids are composed of ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer (Elvax 150), cyclohexanone resin (Laropol K80), ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer (A-C copolymer), phthalate ester of hydroabietyl alcohol (Cellolyn 21), and petrolatum (paraffin). Conservation Support Systems P.O. Box 91746 Santa Barbara, Calif. 93190-1746 GelatinSupplied in sheet form Kremer Pigments Inc. 228 Elizabeth St. New York, N.Y. 10012 Goldbeater's skinTalas 568 Broadway, #107 New York, N.Y. 10012 Natural skin condomsMost drugstores Orasol dyesManufactured by Ciba-Geigy. Soluble in both alcohol and ketone solvents. Conservation Support Systems P.O. Box 91746 Santa Barbara, Calif. 93190-1946 Polyvinyl acetate resins100% solids Conservation Support Systems P.O. Box 91746 Santa Barbara, Calif. 93190-1946 Sausage casingsYour neighborhood butcher Silicone MylarDouglas Hanson P.O. Box 528 Hammond, Wisc. 54015 Conservators' Products Co. P.O. Box 411 Chatham, N.J. 07928 Teflon FilmPlastomer Products AUTHOR INFORMATIONLISA KRONTHAL received a B.A. in art history from the University of Rochester in 1988 and an M.A. and certificate of advanced study in art conservation from the State University College at Buffalo in 1993. She pursued her graduate internship at the Brooklyn Museum of Art focusing on archaeological conservation, specifically working with ancient Egyptian collections. She began working at the American Museum of Natural History as an assistant objects conservator in 1994 and remains there as an associate conservator in the Anthropology Division, specializing in archaeological and ethnographic objects. She is a Professional Associate of AIC and currently co-chairs the conservation committee within the Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections (SPNHC). Address: Anthropology Division, American Museum of Natural History, 79th St. at Central Park West, New York, N.Y. 10024.

Section Index Section Index |