THE TREASURY BUILDING FIRE OF 1996: PROTECTING CULTURAL RESOURCES IN A NONMUSEUM ENVIRONMENTPaula A. Mohr

3 3. THE DISASTERThe fire, which started during a roof construction project over the north wing, was located in an unoccupied space under the roof and above the fifth-floor ceiling. While much of the building is constructed of noncombustible materials, the roof has been altered from its 19th-century design, and it was 20th-century wood decking and insulation that caught fire. Because of the inaccessible location of the fire, buried under built-up roofing material, it was difficult to extinguish and burned for approximately six hours. During this period, the D.C. Fire Department flooded the roof with several hundred thousand gallons of water, which passed through the building to the basement. The Treasury Building, which is normally protected by the U.S. Secret Service, was also placed under the control of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) on the evening of the fire. The building was closed while investigators documented the scene and the building was checked for structural stability. Its electrical power had been turned off earlier in the day as a safety precaution. On the evening of the fire, using sketchy and sometimes conflicting information concerning the damage to the building and its contents, the curatorial staff developed plans for addressing the collection on the following day. Although the staff deferred making a decision about the collection until the objects could be examined, a tentative determination was made to remove all objects in the north wing to an off-site storage facility. Staff members anticipated that the building would be extremely humid and that the significant amount of water in the building had made plaster ceilings and heavy plaster cornices unstable. They also anticipated that the recovery operation itself would pose further risk to the collection. The immediate emergency procurement authority given to each principal significantly enhanced responsiveness to the emergency. For the Curator's Office, the ability to quickly obtain the services of conservators, art handlers, storage companies, and other specialists was critical in protecting the collection from further damage and deterioration. On the evening of the fire, contact was made with painting and frame conservators to solicit their assistance. Arrangements were also made with a local fine arts shipper to have trucks and personnel available to remove an undetermined number of objects from the building the following day. The curatorial staff, conservators, art handlers, and volunteers assembled on the sidewalk the next morning. This team's access to the building was delayed until midafternoon, when the building was determined to be safe for limited access. Good working relationships with a number of Washington-area conservators enabled the staff to use individuals who knew the collection and its general condition. Because these conservators needed little orientation to the building and the collection, they were able to quickly perform a preliminary survey of the collection's condition. In consultation with the staff, a course of action was determined and a list of priorities developed. After it was confirmed that the plaster ceilings were indeed wet enough to make them unstable and that humidity levels in the building were excessive, it was decided that objects directly affected by smoke and water damage would be relocated to off-site storage. The secretaries portrait collection, displayed in the third-floor corridor, was the first priority because of the excessive amount of water in this area (fig. 1). These paintings also received the most smoke damage. Approximately half of the portrait collection was taken to a storage facility, where conservators removed the paintings from frames to facilitate drying and vacuumed the reverse of the canvases. The team worked until dark that evening, removing as many objects from the building as possible. Evacuation of the rest of the objects continued the next day.

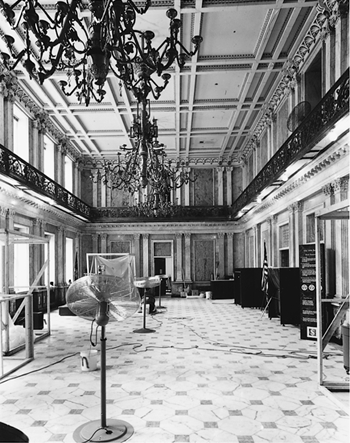

Objects from Treasury's decorative arts collection, which includes large overmantel mirrors and heavy case pieces, were more difficult to remove. Because of their familiarity with the installation details for these pieces, staff from Treasury's Cabinet Shop took responsibility for demounting and disassembling these large objects, which were then turned over to the fine arts handlers, who had staged their trucks on Pennsylvania Avenue. Three mural-size photographic prints from the early 20th century were the only objects that staff members were not able to remove immediately because of their proximity to asbestos, which had been disturbed during the fire. When all of the objects were secured in the storage facility, a thorough examination was made. Fortunately, most of the damage was from smoke and ambient humidity in the building rather than from direct contact with water. One of the biggest challenges for the curatorial staff during the recovery operation was responding to the activity and momentum associated with reopening the facility for occupancy. Although the fire was limited to the north end of this 400,000 sq. ft. building, the corridors and open staircases allowed smoke to permeate the entire structure. HVAC systems throughout the building were also affected and had to be cleaned. Within two days, electricians, abatement crews, and other laborers populated the building, carrying ladders and equipment. A fire recovery contractor was hired to completely clean the interior, a job that included wiping down every surface in the corridors and offices. In the building's restored spaces (fig. 2), where there is a high concentration of objects, fragile decorative painting, and reproduction textiles, the curatorial staff worked with the cleaning contractor to identify gentle cleaning techniques and materials. The contractor recommended use of a commercially made dry sponge for wooden objects that we approved in consultation with the conservators. Fragile finishes such as walls with decorative painting and mirrors with gilded surfaces were not cleaned. Treasury docents and volunteers from the Treasury Historical Association were quickly trained by the curatorial staff in the proper handling of objects and the approved cleaning methods. These individuals, in turn, were assigned to each of the restored rooms to provide supervision for the cleaning staff and to assist with handling objects.

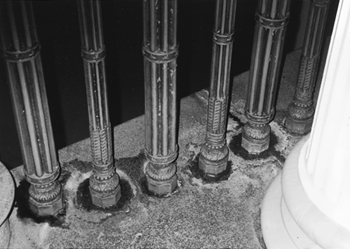

The curatorial staff's second concern was for the remaining 1,500 objects displayed in executive offices throughout the building. In the effort to reoccupy the building as soon as possible, these offices were also slated for thorough cleaning. Again, working with the cleaning company, the curatorial staff determined that the antique furniture would be cleaned with a dry sponge. Artwork and gilded objects such as mirrors were not cleaned. As a further precaution and reminder to cleaning staff working without supervision, gilded objects and works of art throughout offices in the building were tagged. These objects, which remained, and the more severely affected objects in the fire-damaged north wing were later cleaned and restored by conservators. When the collection was stabilized and safe, the staff turned its attention to the building. One of the first action items was to obtain the services of a preservation architect, who helped develop guidelines for protecting the building during the cleanup operation. This task included developing a list of dos and don'ts for workers that were simple, yet important in protecting building fabric. Some consideration was given to having the preservation architect conduct a brief workshop for workers to sensitize them to the building. While the frequency with which these crews were changed made this idea impractical, this idea could be useful for a smaller site. The preservation architect provided the curatorial staff with a priority list for preventive work. All wet carpets and pads were removed to facilitate drying of floors and to help lower humidity levels. All other wet material, including fabrics, acoustical tiles, and papers, was to be removed as well. The staff was advised to slowly lower the humidity in the building to allow materials to respond gradually. Because the central air-conditioning system was shut down for cleaning, window air conditioners were installed in the smaller restored rooms to lower the humidity. The north wing, where the fire took place, has a great deal of structural and decorative cast iron, which was problematic because of the excessive amount of water that seeped through the building. For example, cast-iron pilasters that line the corridors are decorative, but they also conceal chases that are open from the roof to the basement. Two granite staircases in the north wing of the building carried much of the water to the basement during the fire, and water that seeped into the hollow cast-iron balusters of the staircase posed a serious conservation problem (fig. 3). The recovery contractor was instructed to regularly wipe up the water as it wept out of the base of balusters, as well as any other standing water, particularly on cast-iron thresholds, at the base of cast-iron columns and pilasters, and adjacent to iron door frames.

The Cash Room, Treasury's 19th-century banking room, is located two floors under the fire and sustained extensive water damage to the plaster ceiling and marble walls (fig. 4). The preservation architect recommended that small holes be made at regular intervals in the ceiling to facilitate drying. Treasury was also advised to dry the room slowly to minimize stressing the architectural finishes in the room. Portable air conditioners, floor fans, and portable dehumidifiers were brought into the room. Water also seeped into the three large bronze chandeliers that had been recreated for the room in 1987. Treasury's electricians removed the bottom pendants of the chandeliers to drain the water and facilitate drying of the fixtures' interiors. An ornate bronze balustrade located on an iron balcony on the upper level of the room also sustained water damage. Ferrous fasteners in contact with the bronze caused significant corrosion.

The staff also began to plan for the necessary demolition of damaged architectural features such as the roof trusses, the fifth-floor ceiling, and damaged plaster. While removal of damaged building materials did not begin for several weeks after the fire, the preservation architect began to survey the building for the purpose of identifying original fabric so that we could provide the contractor with a list indicating the materials that could be demolished and what needed to be preserved. |