THE TREASURY BUILDING FIRE OF 1996: PROTECTING CULTURAL RESOURCES IN A NONMUSEUM ENVIRONMENTPaula A. Mohr

ABSTRACT—ABSTRACT—What happens when there is a fire in your building? The inconceivable happened on June 26, 1996, when a fire broke out on the roof of the Treasury Building in Washington, D.C. The result was a destroyed roof, a smoke-filled building, and significant water damage on the six floors located under the fire.The Treasury Building (1836–69) is a National Historic Landmark and was constructed after a disastrous fire in 1833 to provide the nation's finance ministry with a fireproof building. In addition to this important architectural resource, the Treasury retains a significant collection of fine and decorative arts. These objects, which are displayed in public and private spaces throughout the building, include portraits of secretaries of the treasury, historic currency displays, and 19th-century furniture and artifacts.This article will focus on decision making and procedures that were successful in responding to this emergency. A special focus will be placed on response operations in a government office building where numerous bureaus, departments, and competing interests must be addressed in the recovery operation. Gaining access to a highly secured building (and one that had been classified as a crime scene after the fire), procuring services, handling hazardous materials and abatement, and coordination with other recovery operations will be discussed.The response by the Curator's Office was focused on two distinct areas. First was the response relating to the Historic Treasury Collection. Specifically, the evacuation of objects from an unstable, humid environment, relocation to off-site storage, and initial assessment and cleaning of other objects will be discussed. Second, the article will discuss the response required to protect the building fabric. TITRE—L'incendie du b�timent du tr�sor public en 1996: prot�ger le patrimoine culturel dans un contexte autre que celui du monde des mus�es. R�SUM�—Que se produit-il quand le feu se d�clare dans votre b�timent ignifug�? L'inconcevable se produisit le 26 juin 1996, quand un incendie �clata dans la toiture du b�timent du tr�sor � Washington, D.C. Le r�sultat en fut un toit d�truit, un b�timent rempli de fum�e et des dommages importants caus�s par l'eau sur les six �tages situ�s plus bas.Le b�timent du tr�sor (1836–69) est un monument class� qui fut construit � la suite d'un incendie d�sastreux en 1833, afin de pourvoir le minist�re des finances de la nation d'un immeuble ignifug�. En plus de cet important patrimoine architectural, le Conseil du tr�sor maintient une collection significative d'�uvres et d'objets d'art. Ces collections, qui sont expos�es dans les espaces publics et priv�s � travers le b�timent, comprennent les portraits des secr�taires du Conseil du tr�sor, des devises historiques, ainsi que des meubles et des objets datant du 19�me si�cle.Dans cet article, on discutera en particulier de la prise de d�cision et des proc�dures qui furent appliqu�es avec succ�s apr�s le sinistre. Une attention sp�ciale sera pr�t�e aux op�rations d'intervention dans un b�timent administratif o� les conflits d'int�r�t entre de nombreux bureaux et services doivent �tre adress�s pendant les op�rations de sauvetage. L'auteur discutera des points � savoir comment obtenir l'acc�s � un b�timent fortement prot�g� (dont l'incendie avait �t� d�clar� d'origine criminelle), comment obtenir des services, manipuler et enlever des mat�riaux dangeureux, et comment coordonner toutes les op�rations de recouvrement.Les efforts de la part du d�partement de la conservation se sont concentr�s sur deux zones distinctes. La premi�re fut la r�cup�ration de la collection historique du Conseil du tr�sor. L'auteur discutera sp�cifiquement de l'�vacuation des objets d'un environnement instable et humide, leur d�placement vers un autre �difice pour l'entreposage, ainsi que l'�valuation des dommages et le nettoyage initial sur place. En second lieu, l'auteur discutera de ce qu'il fallut faire pour prot�ger le corps du b�timent. TITULO—El incendio del edificio de la tesorer�a (de los EE UU) en 1996: c�mo proteger los recursos culturales en un ambiente que no es un museo.RESUMEN—Qu� sucede cuando en un edificio a prueba de incendios se produce un incendio? Este hecho inconcebible ocurri� el 26 de junio de 1996 al desatarse un incendio en el techo del Edificio de la Tesorer�a en Washington D.C. Los resultados fueron la destrucci�n del techo, el edificio lleno de humo y da�os considerables producidos por el agua en los seis pisos por debajo del piso del incendio.El Edificio de la Tesorer�a (1836–69) es un Monumento Hist�rico Nacional y fue construido luego de un desastroso incendio en 1833, para dotar al Ministerio de Finanzas de la naci�n de un edificio a prueba de incendios. Adem�s de ser una construcci�n arquitect�nica importante, la Tesorer�a alberga una valiosa colecci�n de obras de arte y objetos decorativos. Estos objetos, exhibidos en espacios p�blicos y privados del edificio, incluyen retratos de los Secretarios de la Tesorer�a, exhibiciones de monedas hist�ricas, y muebles y artefactos del siglo XIX.Este art�culo se concentrar� en la toma de decisiones y procedimientos que fueron aplicados exitosamente como respuesta a esta emergencia. Se dar� un enfoque especial a aquellas operaciones realizadas en un edificio de oficinas p�blicas en donde numerosos despachos, departamentos e intereses conflictivos deben ser tenidos en cuenta en la operaci�n de recuperaci�n. Se discutir� el acceso a un edificio de extrema seguridad (que hab�a sido clasificado como la escena del crimen luego del incendio), la obtenci�n de los servicios, el manejo de materiales peligrosos y la coordinaci�n con otras operaciones de recuperaci�n.La respuesta de la Oficina Administrativa se concentr� en dos �reas. La primera estaba relacionada con la Colecci�n Hist�rica de la Tesorer�a. Espec�ficamente, se discutir�n la evacuaci�n de objetos de un ambiente inestable y h�medo, la reubicaci�n en un dep�sito externo y la evaluaci�n y limpieza de otros objetos. En segundo lugar, en el art�culo se discutir�n las acciones requeridas para proteger la estructura del edificio. 1 1. INTRODUCTIONThe Treasury Building fire occurred on June 26, 1996, during a construction project to install a new roof on the building. This disaster caused extensive fire, water, and smoke damage to the historic building and its collection, particularly in those areas located under the fire. This article describes the experience of the curatorial staff in managing the response to the fire and focuses on the effort required to protect cultural assets in a nonmuseum setting. During the aftermath of the fire, the challenge for the curatorial staff was the protection of the historic architecture and the museum collection during an intensive period when recovery operations were directed at returning this federal office building to operational status. 2 2. BACKGROUNDStudents of the history of Washington, D.C., are well acquainted with the federal government's legendary association with fires in the 19th century. The Treasury Department in particular has been plagued with numerous fires during its 200-year history. The first disastrous one occurred in 1814 when the British set fire to Washington's public buildings, including the Treasury. A second and equally devastating fire occurred at the Treasury in 1833, resulting in construction of the present Treasury Building to provide the nation's finance ministry with a “fireproof” building. Begun in 1836 by the architect Robert Mills, the early sections of the building were constructed of sandstone, brick, and quick-setting hydraulic cement. Later additions to the building, constructed in the 1850s and 1860s, employed masonry and segmental arches supported with iron beams. In addition to the noncombustible materials for the structure, the decorative elements in the building, such as door and window architraves, cornices, baseboards, and columns, are made of stone, plaster, or cast iron. The Treasury Building has served as the headquarters for the Treasury Department for more than 150 years. Treasury remains the only one of the four original cabinet-level agencies to remain in the executive complex surrounding the White House. The building's architectural significance is derived from its development as the first large office building in America. When the building was completed, it was a powerful architectural symbol for early Washington, D.C. The Treasury Building was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1972. In addition to this important architectural resource, the Treasury retains a significant collection of fine and decorative arts. Displayed in public and private spaces throughout the building, it includes portraits of secretaries of the treasury, paintings from Treasury's Depression-era art programs, historic currency displays, and 19th-century office furniture. These objects, while they receive museum-quality conservation, are part of a “working” collection and are used by occupants of the building. The restoration program for the building was begun in 1985, and since that time a number of historically and architecturally significant spaces have been restored to their original appearance. These rooms, such as the Civil War–era office of the secretary of the treasury and the space used by President Andrew Johnson as a temporary office in 1865, typically have a high concentration of objects from the Historic Treasury Collection. Other historic rooms, such as the 1869 marble Cash Room, are public spaces and have a high level of interior finish, including marble, decorative bronze work, and ornamental plaster. 3 3. THE DISASTERThe fire, which started during a roof construction project over the north wing, was located in an unoccupied space under the roof and above the fifth-floor ceiling. While much of the building is constructed of noncombustible materials, the roof has been altered from its 19th-century design, and it was 20th-century wood decking and insulation that caught fire. Because of the inaccessible location of the fire, buried under built-up roofing material, it was difficult to extinguish and burned for approximately six hours. During this period, the D.C. Fire Department flooded the roof with several hundred thousand gallons of water, which passed through the building to the basement. The Treasury Building, which is normally protected by the U.S. Secret Service, was also placed under the control of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) on the evening of the fire. The building was closed while investigators documented the scene and the building was checked for structural stability. Its electrical power had been turned off earlier in the day as a safety precaution. On the evening of the fire, using sketchy and sometimes conflicting information concerning the damage to the building and its contents, the curatorial staff developed plans for addressing the collection on the following day. Although the staff deferred making a decision about the collection until the objects could be examined, a tentative determination was made to remove all objects in the north wing to an off-site storage facility. Staff members anticipated that the building would be extremely humid and that the significant amount of water in the building had made plaster ceilings and heavy plaster cornices unstable. They also anticipated that the recovery operation itself would pose further risk to the collection. The immediate emergency procurement authority given to each principal significantly enhanced responsiveness to the emergency. For the Curator's Office, the ability to quickly obtain the services of conservators, art handlers, storage companies, and other specialists was critical in protecting the collection from further damage and deterioration. On the evening of the fire, contact was made with painting and frame conservators to solicit their assistance. Arrangements were also made with a local fine arts shipper to have trucks and personnel available to remove an undetermined number of objects from the building the following day. The curatorial staff, conservators, art handlers, and volunteers assembled on the sidewalk the next morning. This team's access to the building was delayed until midafternoon, when the building was determined to be safe for limited access. Good working relationships with a number of Washington-area conservators enabled the staff to use individuals who knew the collection and its general condition. Because these conservators needed little orientation to the building and the collection, they were able to quickly perform a preliminary survey of the collection's condition. In consultation with the staff, a course of action was determined and a list of priorities developed. After it was confirmed that the plaster ceilings were indeed wet enough to make them unstable and that humidity levels in the building were excessive, it was decided that objects directly affected by smoke and water damage would be relocated to off-site storage. The secretaries portrait collection, displayed in the third-floor corridor, was the first priority because of the excessive amount of water in this area (fig. 1). These paintings also received the most smoke damage. Approximately half of the portrait collection was taken to a storage facility, where conservators removed the paintings from frames to facilitate drying and vacuumed the reverse of the canvases. The team worked until dark that evening, removing as many objects from the building as possible. Evacuation of the rest of the objects continued the next day.

Objects from Treasury's decorative arts collection, which includes large overmantel mirrors and heavy case pieces, were more difficult to remove. Because of their familiarity with the installation details for these pieces, staff from Treasury's Cabinet Shop took responsibility for demounting and disassembling these large objects, which were then turned over to the fine arts handlers, who had staged their trucks on Pennsylvania Avenue. Three mural-size photographic prints from the early 20th century were the only objects that staff members were not able to remove immediately because of their proximity to asbestos, which had been disturbed during the fire. When all of the objects were secured in the storage facility, a thorough examination was made. Fortunately, most of the damage was from smoke and ambient humidity in the building rather than from direct contact with water. One of the biggest challenges for the curatorial staff during the recovery operation was responding to the activity and momentum associated with reopening the facility for occupancy. Although the fire was limited to the north end of this 400,000 sq. ft. building, the corridors and open staircases allowed smoke to permeate the entire structure. HVAC systems throughout the building were also affected and had to be cleaned. Within two days, electricians, abatement crews, and other laborers populated the building, carrying ladders and equipment. A fire recovery contractor was hired to completely clean the interior, a job that included wiping down every surface in the corridors and offices. In the building's restored spaces (fig. 2), where there is a high concentration of objects, fragile decorative painting, and reproduction textiles, the curatorial staff worked with the cleaning contractor to identify gentle cleaning techniques and materials. The contractor recommended use of a commercially made dry sponge for wooden objects that we approved in consultation with the conservators. Fragile finishes such as walls with decorative painting and mirrors with gilded surfaces were not cleaned. Treasury docents and volunteers from the Treasury Historical Association were quickly trained by the curatorial staff in the proper handling of objects and the approved cleaning methods. These individuals, in turn, were assigned to each of the restored rooms to provide supervision for the cleaning staff and to assist with handling objects.

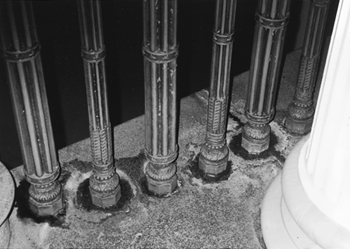

The curatorial staff's second concern was for the remaining 1,500 objects displayed in executive offices throughout the building. In the effort to reoccupy the building as soon as possible, these offices were also slated for thorough cleaning. Again, working with the cleaning company, the curatorial staff determined that the antique furniture would be cleaned with a dry sponge. Artwork and gilded objects such as mirrors were not cleaned. As a further precaution and reminder to cleaning staff working without supervision, gilded objects and works of art throughout offices in the building were tagged. These objects, which remained, and the more severely affected objects in the fire-damaged north wing were later cleaned and restored by conservators. When the collection was stabilized and safe, the staff turned its attention to the building. One of the first action items was to obtain the services of a preservation architect, who helped develop guidelines for protecting the building during the cleanup operation. This task included developing a list of dos and don'ts for workers that were simple, yet important in protecting building fabric. Some consideration was given to having the preservation architect conduct a brief workshop for workers to sensitize them to the building. While the frequency with which these crews were changed made this idea impractical, this idea could be useful for a smaller site. The preservation architect provided the curatorial staff with a priority list for preventive work. All wet carpets and pads were removed to facilitate drying of floors and to help lower humidity levels. All other wet material, including fabrics, acoustical tiles, and papers, was to be removed as well. The staff was advised to slowly lower the humidity in the building to allow materials to respond gradually. Because the central air-conditioning system was shut down for cleaning, window air conditioners were installed in the smaller restored rooms to lower the humidity. The north wing, where the fire took place, has a great deal of structural and decorative cast iron, which was problematic because of the excessive amount of water that seeped through the building. For example, cast-iron pilasters that line the corridors are decorative, but they also conceal chases that are open from the roof to the basement. Two granite staircases in the north wing of the building carried much of the water to the basement during the fire, and water that seeped into the hollow cast-iron balusters of the staircase posed a serious conservation problem (fig. 3). The recovery contractor was instructed to regularly wipe up the water as it wept out of the base of balusters, as well as any other standing water, particularly on cast-iron thresholds, at the base of cast-iron columns and pilasters, and adjacent to iron door frames.

The Cash Room, Treasury's 19th-century banking room, is located two floors under the fire and sustained extensive water damage to the plaster ceiling and marble walls (fig. 4). The preservation architect recommended that small holes be made at regular intervals in the ceiling to facilitate drying. Treasury was also advised to dry the room slowly to minimize stressing the architectural finishes in the room. Portable air conditioners, floor fans, and portable dehumidifiers were brought into the room. Water also seeped into the three large bronze chandeliers that had been recreated for the room in 1987. Treasury's electricians removed the bottom pendants of the chandeliers to drain the water and facilitate drying of the fixtures' interiors. An ornate bronze balustrade located on an iron balcony on the upper level of the room also sustained water damage. Ferrous fasteners in contact with the bronze caused significant corrosion.

The staff also began to plan for the necessary demolition of damaged architectural features such as the roof trusses, the fifth-floor ceiling, and damaged plaster. While removal of damaged building materials did not begin for several weeks after the fire, the preservation architect began to survey the building for the purpose of identifying original fabric so that we could provide the contractor with a list indicating the materials that could be demolished and what needed to be preserved. 4 4. LESSONS LEARNEDAs a result of the fire, a number of important additions have been made to the emergency plan. The plan before the fire focused primarily on emergency situations that related to the public tours. The plan has been greatly expanded to address a range of emergency situations that could impact the building and the collection, including fire, explosion, theft, and power loss. For each emergency, procedures are outlined, assignments and responsibilities are identified, and a list of parties to be notified is provided. During the Treasury fire, access to the building became one of the largest obstacles. As a result, the curatorial emergency plan now includes security clearance information for contractors and their vehicles. The curatorial staff has also placed an emergency cart stocked with rolls of plastic, flashlights, registrarial supplies, disposable cameras, and other items in a nearby building. Finally, once a year the entire collection inventory is printed, and copies are placed in the residences of curatorial staff members. In responding to this emergency, the staff realized the importance of having component parts of objects identified with accession numbers. While this high level of registrarial work is routinely done by most museums, for a collection within a federal building it is unusual. During the Treasury recovery effort, 19th-century bookcases were disassembled quickly and removed from the building. When it came time to reassemble these pieces, matching bookshelves to the proper bookcase and the proper position within the bookcase became a time-consuming effort. During the response, signage became an extremely useful tool, and fortunately the staff had access to a computer. Signs that provided cautions, and requests that fans be left on and doors be left open, were a simple yet effective way for the staff to control the treatment of historic fabric in the damaged section of the building. A visible presence was important, too. The staff attempted to balance attendance at planning meetings with monitoring the activity in the field. While both were important, decisions made in meetings were often transitory and were frequently reversed or modified. Particularly in the beginning, when time was of the essence, it was more valuable to be working with the personnel who were directly involved with the evacuation of the collection and the cleanup of the building. During the cleanup effort, responding to the momentum of getting the building reopened proved to be the most significant challenge. This experience highlighted the reality that in any recovery operation, protecting cultural resources is not done in a vacuum. It may be even more the case in a building that functions as a modern office building and where other issues and goals need to be addressed. A balance of protecting the cultural assets of the building while preserving security and expeditiously returning the building to operational status had to be achieved and maintained. 5 5. CONCLUSIONSIn summary, the factors that enabled the curatorial staff to successfully respond to this disaster were largely dependent upon the availability of trained individuals who assisted in the assessment of damage and developing strategies. Curators responsible for collections and historic buildings should identify conservators, architects, and other specialists and give these professionals the opportunity to learn about the cultural resources at the site prior to a disaster. These are the experts who are critical in supplying technical advice and trained personnel in the event of an emergency. Thinking through possible emergency scenarios and documenting response procedures in a written document is also critical in bringing your curatorial staff together as an effective response team. While it is important to have an emergency plan for cultural resources, it is equally important to understand how that plan fits into the overall emergency plan for the larger organization. The curatorial staff and the specialists who assisted after the fire shared the common goal of protecting the collection and the building, but the most significant challenge was responding to events set in motion by others who were concerned with security and life safety and with making the building operational. AUTHOR INFORMATIONPAULA A. MOHR is curator of the Treasury Building, a position she has held since 1994. She has also held curatorial positions with the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the National Park Service, and the Old Executive Office Building in Washington, D.C. Mohr is a graduate of the Cooperstown Graduate Program in Museum Studies. Address: Office of the Curator, Room 1225, 1500 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20220

Section Index Section Index |