INTERPRETING ARTIST'S INTENT IN THE TREATMENT OF JOHN CONSTABLE'S THE WHITE HORSE SKETCHMICHAEL SWICKLIK

ABSTRACT—John Constable was a landscape painter whose style varied from highly finished to loosely sketched. This article documents the treatment of a painting in which extensive overpaint obscured the artist's goals. It considers how the need to discover the artist's intentions affected the course of the conservation effort. TITRE—L'interpr�tation de l'intention de l'artiste dans le traitement de l'esquisse du cheval blanc (“The White Horse Sketch”) de John Constable. R�SUM�—John Constable �tait un paysagiste dont le style variait entre l'esquisse et le raffin�. Cet article documente le traitement d'une oeuvre couverte de nombreux surpeints qui voilaient le style du tableau. On pr�sente comment la n�cessit� de d�couvrir l'intention de l'artiste �tait au coeur de toutes les �tapes du traitement de cette oeuvre. TITULO—Interpretando la intenci—n del artista en el tratamiento del boceto “El caballo blanco” de John Constable. RESUMEN—John Constable fue un pintor de paisajes cuyo estilo vari� desde el m�s esmerado detalle hasta bocetos indefinibles. Esta investigaci�n documenta un tratamiento donde el exceso de pintura ocultaba cu�l de estos objetivos ten�a en mente el artista. Plantea c�mo la necesidad de descubrir la verdadera intenci�n del artista afect� completamente el rumbo del esfuerzo para su conservaci�n. 1 INTRODUCTIONWhen working with traditional oil paintings, issues of artist's intent rarely are the overriding focus of a conservation treatment. Although such factors as how the artist wanted his painting to look or how it may have appeared when it was finished should always be considered throughout the treatment, it is less common that the conservator needs to consider the painter's precise purpose in producing the work. In painting his landscapes, John Constable (1776–1837) created pictures that ranged from loosely and broadly painted sketches to highly polished and tightly rendered finished paintings, often apparently arbitrarily ending the process at any degree of finish in between. Sometimes he even reworked a painting some years later. Because of these tendencies, it is often difficult to determine whether a work is a less finished exhibition piece or an intentionally roughly worked sketch. Treating Constable's paintings, therefore, often requires a consideration of his objective. The cleaning of a version of The White Horse, 1818–19 (fig. 1, p. 363), in the collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., is a case in point. Treatment was further complicated because the work was painted on top of another painting. This article concentrates on the role of Constable's intentions in creating The White Horse as an impetus and a driving force in its treatment.

2 BACKGROUNDJohn Constable, with J. M. W. Turner among the pre-eminent British landscape painters of the 19th century, was still relatively unknown around 1818–19 when he began painting the National Gallery of Art's version of The White Horse. He painted another version of this painting (of similar scale, approximately 4 � 6 ft) for the Royal Academy exhibition of 1819 (fig. 2, p. 364). This version, dated 1819 and now in the Frick Collection, received critical acclaim and led to Constable's election to associate membership in the Royal Academy.

Although the history of the Frick painting was well documented, the version in the National Gallery of Art had a less certain provenance. It was not recorded in the Constable literature until it appeared in a catalog for the 1872 exhibition at the Royal Academy, which lists it as “118, The White Horse, John Constable, R. A., Canvas, 49 � 70 1/2 in. Lent by John Pender Esq.” It was next recorded as exhibited in 1882 in E. Fox White's gallery in London. The following year a full-page reproduction engraving by O. Jahyer was included as part of an article on Constable in the Magazine of Art (fig. 3, p. 364). In 1893 the picture was purchased from Wallis and Son, London by Peter A. B. Widener. In 1942, his son, Joseph E. Widener, donated it in his memory to the National Gallery of Art (Rhyne 1990).

Although The White Horse was given a prominent position in the galleries upon donation, its appearance, which was somewhat atypical for Constable, gave reason for some discussion. Writing about the painting in 1944, John Walker, then director of the National Gallery, said, “It seems to me a full size sketch

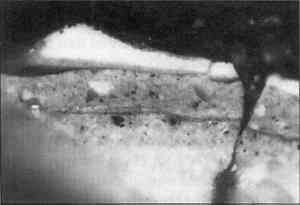

Many issues remained unresolved when conservation treatment was first considered in 1992, including whether the visible composition had been meant as a finished version or as a sketch of The White Horse. If it were a sketch, what could explain its current appearance? Even taking the distortion of the thick, highly discolored varnish into consideration, the painting did not present the visual characteristics of a Constable sketch. The painting was heavy and cumbersome, rather than loose and lively; the paint itself was transparent and liquid, not opaque and thick; the trees were rendered as massive, filled-in, hard-edged shapes, not as Constable's typically brushy, air-filled, irregular forms. In many respects the painting was more like a finished work than a sketch. If heavy repainting explained this look, why had this occurred, and who did it? From the engraving by O. Jahyer in 1883 it was clear that any overpainting would have been in place by that date. Given repainting as an explanation for the painting's appearance, it was not immediately clear whether it had been done by a different person to turn a less 3 EXAMINATIONInvestigation of the painting centered on whether it had been overpainted. The first step was a thorough examination of the paint surface through a binocular microscope. Compensating visually for the heavy layer of discolored varnish, some peculiar features in the upper paint layers were revealed. First, much of this paint had an odd, shriveled appearance. It was also clear that much of the cracquelure in the paint was not caused by the breaking of the paint, but by the shrinking of the upper layers of paint on a surface to which it was not well bound. The shriveling of the A more thorough binocular microscopic examination raised more doubt concerning the upper paint layers. In many areas the opaque, shriveled paint was deposited in cracks in the paint layers beneath it. Although this is usually a concrete indicator for differentiating overpaint from original painting, it was not such a conclusive observation in this case. The x-radiographs showed that there was a painting of Dedham Vale from the Coombs beneath the visible White Horse, but they only suggested that there was another earlier version of The White Horse beneath the obvious one. Therefore, it was difficult to decide if the paint lay in Dedham Vale cracks or in another painting of the White Horse image. In one particularly interesting area of foliage to the left, drying cracks in a layer clearly from The White Horse resulted from being painted directly on top of a thickly painted, bright green field in Dedham Vale that had not yet dried. On top of the cracked White Horse paint and oozing down into its cracks was a somewhat thick, transparent brown paint that covered a good part of the foreground landscape. This layer was clearly later than the layer that formed the initial painting of The Since the investigation of the surface with the binocular microscope indicated that the painting was probably heavily repainted in a hand other than Constable's, scientific analysis was required for confirmation. On the chance of finding more modern paints in these upper layers, pigment analysis in the form of dispersed samples examined with polarized light microscopy was the first method chosen. The results were confirmed with x-ray fluorescence analysis of the elemental compositions. Unfortunately, comparing the results of these tests against a history of Constable's pigment use found primarily earth pigments, lake pigments, white lead, black, and Prussian blue, all relatively common on Constable's palette (Cove 1991). Although mixtures in the trees contained a high propotion of emerald green, a pigment found less frequently in Constable's practice, the evidence clearly was not strong enough to establish that this paint was applied later. These results would seem to argue against the upper layers being overpaint. However, since it was known that any repainting would date prior to 1883, and because all the pigments in Constable's repertoire could have also been used later in the century, finding all common 19th-century pigments was not unexpected. Because simple pigment analysis did not prove helpful in this case, sampling by cross section was indicated. Cross sections from several different areas of the painting were taken, mounted, and analyzed through the microscope. Each sample shares an important feature with the two that are illustrated (fig. 6, p. 365). A heavy layer of varnish is visible between two paint layers, with thick applications of paint above the varnish and thin applications below it. In the thinner lower layers there are two distinct campaigns of painting separated by a thin layer of oil. Figure 6 is a cross section taken from the roof of the cottage in the central area of the foreground. It was hypothesized that the layers beneath the oil layer were from the lower painting, Dedham Vale from the Coombs, and that the similar layers just above the oil layer were from the original painting of The White Horse. One notable feature of both layers is their relative thinness and “neatness”; both

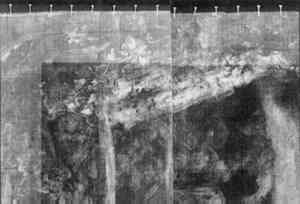

The later overpaint was so heavy as to almost completely obliterate what was beneath it. From the beginning, the study of the x-radiographs, particularly in the area of Willy Lott's cottage in the middleground, suggested that another version of The White Horse existed beneath the visible one. The evident form on the surface depicted only a single gable on the cottage, but Constable had painted this cottage many times from many different angles, always depicting it as it appeared in nature: as an L-shaped structure with two perpendicular wings and two gables in view. Invariably, the misunderstood representation of the house as it appeared was used by those who argued against the painting's authenticity and was itself another indication that the overpaint had been applied by a different painter. But in the x-radiograph it was clear that a properly rendered painting of the cottage existed beneath the one on the surface. Together with the evidence supplied by the cross sections that there were two distinct campaigns of similarly applied paint underneath the surface paint, it was virtually certain that there was some other version of The White Horse by Constable beneath the visible one. The treatment then required that the demonstrably later overpaint be removed to regain the original artist's intention. 4 CLEANINGBecause the overpaint was so heavy, it was not possible to ascertain the precise condition of the original painting prior to its removal. However, some clues were provided early in the cleaning that gave hope for a good result. The painting was covered not only with heavy, opaque repaint, but with a thick layer of markedly discolored varnish. Since it was a relatively simple task to remove this coating from the overpaint without affecting it, the varnish layer was removed first. The painting became brighter, but it did not appear technically any more like a painting by Constable. However, removing this varnish fortuitously revealed two areas where previous attempts at cleaning the painting had removed the overpaint layer to reveal what was beneath it. One area, in the upper right corner, showed the feathery, active brushwork of a Constable sketch in the clear, bright color that this area of the sky in the Frick version also displayed. Although this triangular area measured only 3 Painstakingly, the repaint was removed using organic solvents and the aid of a binocular microscope, one square inch at a time, over several years (1992–97, not working every day). To universal delight, a stunning, fresh, lively, and well-preserved fully realized sketch for the Frick painting was revealed (fig. 8, p. 366).

5 FOCUSING ON INTENT: FURTHER DISCOVERYAfter viewing the cleaned painting, any doubt about the outcome of the overpaint removal disappears. When considering the treatment options, however, the likelihood of success seemed remote. Only through detailed research on the artist's working methods did the hope emerge that this painting could have been by Constable. At every level of the investigation, whether by art historian or conservator, the knowledge that Constable almost always produced a full-sized sketch for a major finished work pushed the research forward. When Charles Rhyne requested a new set of x-rays for his 1984 study he was looking for evidence of Constable's sketchy style beneath the murky surface. To his surprise he found that the canvas had been reused in such a way that the artist's involvement was virtually guaranteed. The conservator's complex efforts to justify the removal of the overpaint were compelled by the likelihood of finding this sketch. The thickness of the overpaint with its variable solubilities; the multiple layers of both original and nonoriginal paint, each with its own cracquelure; and the somewhat solvent-sensitive original paint combined to make the process less than clear. Ultimately, knowledge of Constable's sketchy style of paint application—with its energetic activity, feathery touch, and characteristic skipping of dry scumbles over the tops of the canvas threads—was the guide. The overpaint removal revealed that Constable had originally planned to execute a sketch for The White Horse on top of his painting of Dedham Vale. However, his reasons for obliterating his initial composition and what he had originally hoped to accomplish in painting it was yet another focus of the investigation. It would be of interest to know whether the Dedham Vale painting had also been a sketch, making it the first of the six foot sketches, or whether, as Rhyne proposed, Constable had executed his first large finished composition on this canvas and abandoned it, presumably because he had not worked the details out in a full-sized sketch beforehand (Rhyne 1990). Rhyne provided some interesting evidence supporting this point of view. He focused primarily on details from the x-radiographs that appeared to show the two buildings in the middleground with a connecting bridge as highly finished elements. However, the version of Willy Lott's house as seen in the x-radiograph seems equally polished; as one of the more finished elements in the now-visible sketch it does not appear at all out of place. Other evidence revealed in the treatment opens the possibility that the same could have been true for the painting underneath. A look at the overall x-radiograph shows that there originally had been a large tree mass in Dedham Vale that rose from lower left to upper right almost to the top of the sky (see A detail of the x-radiograph from the lower left of the painting reveals other relevant information (fig. 9, p. 367). In this area there once was a large, left-leaning tree trunk with a leafy vine climbing it, framing the left foreground of Dedham Vale. Although he painted out the tree trunk in creating the White Horse sketch, Constable left the lower part of the vine to meander about the wooden timbers that lead into The White Horse from the lower left. The vine is painted schematically enough that its inclusion into the sketchy White Horse is not at all out of place.

In sum, the quality of the paint that remains from Constable's first attempt on this canvas seems more like that of his sketchy style than that of his finished style. From the broad nature of this visible work, it is clear that had Constable been attempting a finished version of Dedham Vale, he did not get very far along before he realized that he would need to create full-size sketches for his future large compositions. Just as it is clear from removal of the overpaint that Constable had always intended to create a sketch for The White Horse on this canvas, paradoxically, by revealing the painting, an understanding of his purpose to do so seems even more elusive. Basil Taylor (1973, 38) asked about these large sketches: “Were they rejected solutions abandoned early, full scale modelli, or alternative versions kept in progress with the others in which alternative possibilities could be tested?” Or was the problem, as Kenneth Clark (1946, 14) suggested, “to preserve the vigor and integrity of his studies on a 6 ft. canvas?” Looking at a detail of the paint application from the revealed sketch, it is certainly possible that the latter explanation has an element of accuracy (fig. 10, p. 367). This detail from the area of the sky just above the tree at the right shows paint application that is both energetic and complex. Initially, the paint is applied first in an opaque, liquid form with pink and blue tones blended together. Constable then vigorously brushes into the paint with a dry brush to create strong vertical brushstrokes. Scraping with the end of the brush provides horizontal movement just below. Some dark, feathery applications of blue on top give the feeling of wispy storm clouds. Finally, he swipes across with a wide, well-textured, impastoed stroke in white and bright pink, scraping into it again in a fat vertical stripe to create movement and textural interest. The execution is masterful. One has the sense that Constable is pushing his skill in paint application to its limits. It is undeniable that in this detail, and in much of the rest of the sketch, a passion for the process of painting is evoked. Perhaps Constable found it so unsatisfying to be unable to expose this passion in his entries to the Royal Academy exhibitions that the sketches became the more personally fullfilling part of his process.

The changes in composition that occur from the revealed sketch to the more “finished” Frick painting suggest that Taylor (1973) was 6 CONCLUSIONSThroughout the treatment of this painting, concerns associated with Constable's intentions unavoidably surfaced. Exploration of these issues before treatment helped provide the reason for undertaking the task. Throughout the overpaint removal, confusion was alleviated by thinking about Constable's probable purpose and by gaining familiarity with his sketchy style through studying his other paintings. After the treatment was completed, contemplating the details that were uncovered and their implications gave yet another perspective on Constable's intentions. Now that Constable's first completed large sketch is revealed, other insights into his motivations in its production are undoubtedly forthcoming. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSI would like to thank the National Gallery of Art for supporting this project. Particular thanks go to the curators, Nicolai Cikovsky Jr. and Franklin Kelly and the conservation administrators, Ross Merrill, David bull, and Sarah Fisher, for their day-to-day input. The insights of Charles Rhyne, who had studied this painting in depth, were especially vital early in the project. The scientific analysis provided by Barbara Berrie was especially invaluable. Finally, thank you to Carol Christiansen and Mary Sebera for their editorial assistance. REFERENCESClark, K.1946. Hogarth, Constable, and Turner. In Masterpieces of English painting. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago. 14. Cove, S.1991. Constable's oil painting materials and techniques. In Constable, ed.L.Parris and I. FlemingWilliams. London: Cross River Press. 493–521. Hozee, R.1977. L'opera completa di Constable. Milan, Rizzoli. 149. Rhyne, C. S.1990. Constable's first two six-foot landscapes. Studies in the History of Art 24. Washington, D. C.: National Gallery of Art, 112, 120. Rhyne, C. S.1994. Deaccessioning John Constable. CAA abstracts, College Art Association Annual Meeting, New York. New York: CAA. 9–11.

Rhyne, C. S., and M.Swicklik. 1994. Intent in Constable's full size sketch for The White Horse. AIC preprints, American Institute for Conservation 22nd Annual Meeting, Nashville, Tenn. Washington, D.C.: AIC. Taylor, B.1973. Constable: Paintings, drawings and watercolors. London: Phaidon. Walker, J.1994. Letter to Herbert L. Satterlea, Curatorial files, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.. AUTHOR INFORMATIONMICHAEL SWICKLIK received his M. A. in art conservation from the State University of New York, Cooperstown, in 1982. He has been a conservator of paintings at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., since 1984. His other publications concern the techniques of Van Dyck and the use of varnish by French painters. Address: 105 Woodlawn Rd., Baltimore, Md. 21210-2544.

Section Index Section Index |