ALFRED STIEGLITZ'S PALLADIUM PHOTOGRAPHS AND THEIR TREATMENT BY EDWARD STEICHENDOUGLAS G. SEVERSON

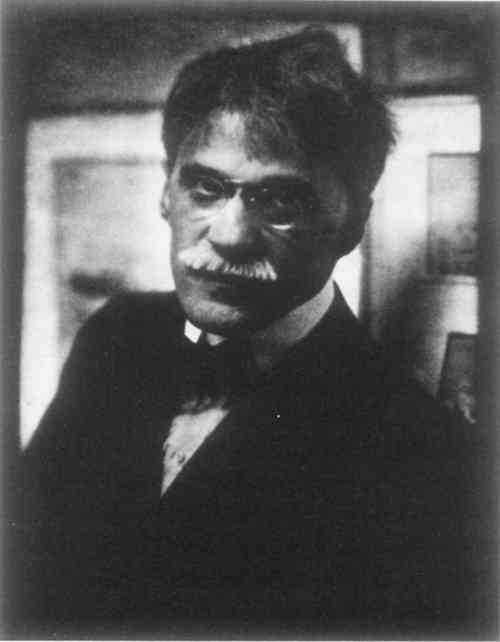

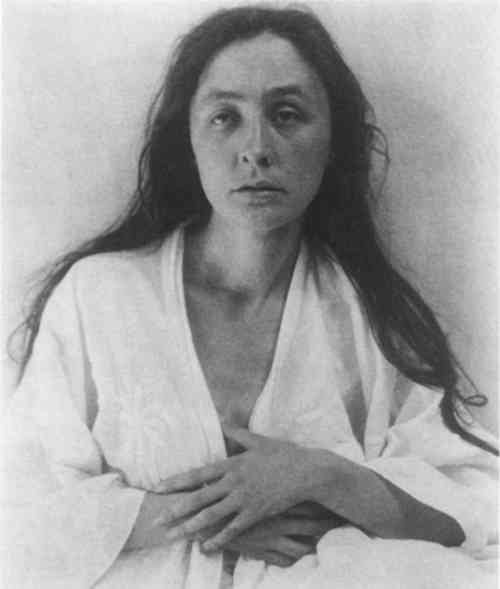

ABSTRACT—The majority of Alfred Stieglitz's palladium photographs were treated after his death by fellow photographer Edward Steichen. The exact nature of the treatment is uncertain, but now, decades later, it may be having an adverse impact on the photographs. This paper summarizes historical and experimental investigations undertaken to clarify this issue. The platinum-palladium process is briefly described, as is a chronology of Stieglitz's use of particular processes and techniques. Events of 1946–51 are related, including the examination and distribution by Georgia O'Keeffe of Stieglitz's lifework and the treatment of more than 230 of his palladium prints by Steichen. Densitometric studies of treated palladium prints in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago are summarized. The observed effects of the treatments are described, and the possible nature of Steichen's procedures is hypothesized. 1 INTRODUCTIONThe photographs of Alfred Stieglitz have inspired, mystified, provoked, and illuminated viewers for more than a century. Stieglitz was born during the Civil War, but his images and ideas are often central to discussions of the most contemporary photography (fig. 1). Stieglitz's portraits of his wife, Georgia O'Keeffe, made over a period of nearly 20 years, are perhaps his most celebrated and timeless images (fig. 2). The prints were executed with a variety of photographic techniques and styles. A hand on an automobile may be rendered in silver for greater contrast, while a softly lit neck or torso is printed with platinum salts to emphasize the subtlety of tonal gradation. Stieglitz's use of the palladium process, by itself or in combination with platinum, is the primary focus of this investigation.

The vast majority of Stieglitz's palladium prints were treated shortly after his death by his fellow photographer Edward Steichen. The exact nature of this treatment is uncertain. The following passage from a letter written by Georgia O'Keeffe in January 1950 (O'Keeffe 1950) to Daniel Catton Rich, director of the Art Institute of Chicago, is the most explicit reference yet found to the procedure. It refers to untreated prints that were already in the Art Institute pending acquisition:

Decades later, this mysterious treatment may be having an adverse impact on these photographs. It is hoped that a discussion of the changes that have occurred in these palladium prints will contribute to our understanding of the stability of these objects and enable us to make better-informed decisions about their storage and exhibition. 2 STIEGLITZ'S TECHNIQUESAlfred Stieglitz began photographing in 1883 as a student in Berlin, where he quickly developed a fondness for the British-made platinum papers. Years later, he claimed to have used platinum “exclusively for the first 35 years of [his] career” (Stieglitz 1934), but this claim is not entirely correct. His first Berlin student pictures were printed on silver gelatin paper, and he often made enlarged carbon prints for exhibition in the photographic salons at the turn of the century. As a partner in the Photochrome Engraving Company in New York City in the 1890s, he learned the subtleties of the photogravure process, which he would later use to make masterful gravure prints for exhibition and for Camera Work. He also made many lantern slides and experimented with other techniques that were popular at the time, such as gum bichromate (Thompson 1993). Stieglitz's technical curiosity and reputation for problem solving are well documented. He published many notes and articles in the photographic journals of his day, describing a variety of processes and procedures (Greenough 1973). But the platinum and palladium process most attracted Stieglitz and held his loyalty for nearly 40 years. He wrote (Stieglitz [1898] 1905, 122):

From 1917, the year that he closed his 291 gallery and began to photograph Georgia O'-Keeffe, until the mid-1920s, Stieglitz explored the capabilities and limitations of the palladium Stieglitz had continued to print certain images in silver throughout this period, and when he began in earnest to photograph clouds, his famous Equivalents, in the early 1920s, he moved away from the platinum and palladium process (Bry 1965). Nearly all of his sky pictures and portraits made after 1923 are silver gelatin prints. In fact, even when he found 22 old negatives in his attic in Lake George in 1934 and reprinted them for a show at his gallery An American Place, he did so with commercially available silver gelatin paper. Due primarily to his declining health, he stopped photographing in 1937, and made his last few prints in 1939. 3 THE PLATINUM AND PALLADIUM PROCESSThe platinum process was patented and introduced to the marketplace under the name Platinotype by the Englishman William Willis in 1873. One of its earliest and most skilled practitioners was Peter Henry Emerson, who was much admired by Stieglitz for his efforts on behalf of photography as an art form and who in 1887 awarded Stieglitz the first of his many medals and prizes in photography. Emerson expressed his admiration for the platinum process in his textbook, Naturalistic Photography (Emerson 1899, 135–36):

Making a platinum or palladium print involves the sensitization of paper with ferric oxalate and platinum or palladium chloride. Light exposure reduces the ferric salts, and the exposed paper is then immersed in potassium oxalate, which catalyzes the reduction of the platinum or palladium salts to the final metallic image material. Unwanted iron salts remain in the paper, however, and must be eliminated by several baths in dilute hydrochloric acid and a final water wash. (For more detailed information on the chemistry of the platinum and palladium process, see Gottlieb 1993, 1995.) The resulting print is made up of finely divided metallic platinum or palladium embedded in the fibers of the paper surface. That surface is completely matte and can therefore be viewed from any angle, as there is no emulsion or subsequent gloss. A variety of papers can be used, and contrast can be varied by dilutions of the sensitizer and other manipulations (Reinhold 1991). But the primary advantage of the platinum or palladium process in comparison to the silver process, which preceded and succeeded it, is that it can reproduce a much longer tonal scale. A full-scale platinum or palladium print from a properly rendered negative has an unmatched tonal beauty. Platinum and palladium have been described here interchangeably because both are based on the light sensitivity of iron salts, and the printing and processing procedures are nearly identical. They can even be mixed together in the same sensitizer. However, there are some differences between the two metals that are of considerable significance for this investigation. While palladium appears in Willis's original patent specifications (Willis 1880), it was not widely used until 1916 when the British government forbade the use of platinum for photography because it was needed for the war effort. In June 1916 the Eastman Kodak Company also Until recently, both platinum and palladium prints have had an excellent reputation for stability and permanence, primarily because the metallic platinum or palladium that forms the image is more resistant than silver to attack from peroxides and other oxidants. However, acidity introduced by the clearing bath can threaten the paper support, and it now appears that palladium prints in particular may be more prone to staining or discoloration than was previously expected. 4 STEICHEN'S TREATMENTHaving survived a number of heart attacks, Alfred Stieglitz finally succumbed to a massive stroke on July 13, 1946. Georgia O'Keeffe had hastily returned from New Mexico and was at his side at the Doctors Hospital in New York when he died. She buried his ashes near the water at Lake George and then returned to Abiquiu until the end of November, perhaps to gather energy for the daunting task ahead: in 1937 she had been named Stieglitz's executrix. The estate included roughly 850 paintings, drawings, and sculptures, at least 2,000 photographs, and some 50,000 letters and papers, all of which were designated for donation to nonprofit institutions. To assist with the sorting and distribution of the works she engaged Doris Bry, who became indispensable as O'Keeffe's assistant and representative for the next 30 years. Bry is described by one O'Keeffe biographer as “meticulous, hardworking, and reliable; she had an excellent eye; most important, she was tough enough to represent her employer's interests in New York while O'Keeffe was in Abiquiu” (Eisler 1991, 481). According to Bry, the Stieglitz Collection was housed and sorted at An American Place over a period of three years. The work was spred throughout the closed gallery space during the winters when O'Keeffe was in town (Bry 1993–94). Selections were made for exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in 1947, with the assistance of James Sweeney, and at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1948, with the assistance of Daniel Catton Rich (O'Keeffe 1949). Edward Steichen (fig. 3), MOMA's new director of the Department of Photography, soon became involved as well. According to Bry, O'Keeffe felt that Steichen was “about the only photographer around who knew the old palladium and platinum printing processes as Stieglitz knew them, and who also had enough regard for Stieglitz that he would take on such a chore” (Bry 1993–94).

Steichen had first met Stieglitz at the urging of Clarence White at the New York Camera Club in 1900. They spent only an hour together before Steichen was off to Paris, but it was enough to establish a rapport (Steichen 1963). When Steichen returned to New York in 1902, he opened a portrait studio at 291 Fifth Avenue, which soon became the legendary Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession. Stieglitz is widely credited with introducing to the American public the work of Rodin, Matisse, C�zanne, Rousseau, Picasso, and Toulouse-Lautrec. Often lost in the shuffle is the fact that Doris Bry's recollection is that Steichen came to An American Place sometime during the sorting and distribution process, probably during the winter of 1949. They focused their attention on the palladium prints, which, according to Bry, were “very, very yellow and gave you a feeling of disturbance” (Bry 1993–94). Arrangements were made for Steichen to treat them, and “they came back looking clear and fresh … newly made again” (Bry 1993–94). As it generally fell to Bry to transport the prints to and from Steichen for treatment, she recalls asking him a number of times to specify the procedure, but he always remained secretive. She is not at all surprised that no written record of the treatment method seems to exist. Fortunately she was a methodical record keeper and placed the notation “Treated by Steichen” on the original mats of all treated pictures, along with treatment dates, which range from May 1946 to June 1950. While not every collection has been examined, 232 treated photographs have so far been found, listed below:

Although a concerted effort has been made to discern patterns among these photographs, many factors make this attempt exceedingly difficult. An unmanipulated platinum or palladium

Add to these factors Stieglitz's known history as a great experimenter and technical pioneer, and the absence of specific records or printing procedures, and the challenges in making positive process identifications become evident. Stieglitz's copious correspondence with his peers provides tantalizing but usually inconclusive or contradictory clues about his techniques. Given the uncertainties of the palladium process itself, the manner in which it was manipulated by Stieglitz, and the contradictions of the written record, any assessment of the condition of the treated prints before and after treatment must be imprecise and largely hypothetical. Still, their assessment must be attempted if responsible decisions are to be made in caring for these photographs. 5 EXHIBITION AND PRINT MONITORINGAttention was first focused on Steichen's treatment of Stieglitz's photographs in 1984 when one of the Art Institute of Chicago's treated palladium portraits of O'Keeffe changed noticeably while on loan to an exhibit in Japan. This change was determined by monitoring the print before and after the exhibit with a reflection densitometer, which bounces a controlled beam of light off any selected 3 mm diameter spot on the image. The light is measured through four colored filters to produce a set of numbers that constitute the reflection density of that particular spot at that particular time. By carefully marking location on a polyester overlay sheet, the precise location can be measured again to determine change. Representative highlights, midtones, and shadows, along with any suspect areas, such as a stain, are monitored in this manner so that future loan decisions can be based upon actual stability data from previous exhibitions (Wilhelm 1981). When the National Museum of Art in Osaka chose to mount an exhibition in 1984 of 180 photographs from the collection at the Art Institute of Chicago, densitometric monitoring as a museum conservation technique was in its infancy. It was decided to conduct a pilot study, and 38 prints were selected to be monitored. Most of these were chosen because of some suspected instability or processing inadequacy. A Stieglitz palladium portrait of Georgia O'Keeffe (fig. 4) was monitored primarily as a standard for comparison, since it was assumed at that time that platinum and palladium prints were extremely stable. However, readings made upon the print's return to Chicago showed significant yellowing at all density levels (Severson 1986).

A number of possible explanations were offered for the changes that occurred in this and several other monitored prints. Reliable data about light levels in the exhibit galleries were not available but may have been quite high, according to the Art Institute curator who acted as courier for the loan. During the exhibition, the gallery temperature was unusually low, which by itself would be beneficial for the photographs but could also result in higher humidity levels that could accelerate deterioration. Based upon this study, and subsequent revelations of the lack of information about Steichen's treatment of the palladium portraits, restrictions were placed on the loan and exhibition of these photographs pending further investigation. The prints were kept in the Art Institute's refrigerated storage vault (at 60�F and 40% RH) and monitored periodically. No further changes were found in figure 4 or any other treated palladium print. Then in 1988, 19 of the O'Keeffe portraits by Stieglitz (including 12 palladium prints) were exhibited under very carefully controlled conditions in the Art Institute's Photography Gallery. No changes were found in the monitored prints after exhibition, including figure 4. Since that time treated palladium prints have been exhibited in carefully controlled conditions at the J. Paul Getty Museum and included in a traveling exhibition organized by the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. Extensive monitoring, in some cases with a colorimeter and a spectrophotometer as well as a densitometer, has indicated that no further significant tonal changes have occurred in these prints during exhibition. 6 EFFECTS OF STEICHEN'S TREATMENTAs O'Keeffe sorted through the photographs of Alfred Stieglitz in the late 1940s, she selected the best mounted print of each image for what she called the “key set” of his work, later given to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Given the historic importance and value of these photographs, and the many unanswered questions surrounding Steichen's treatment of them, the National Gallery organized and hosted a colloquy on the subject in May 1993. Steichen-treated palladium prints were brought from the Getty Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago, and matching untreated prints were brought from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. These photographs and their counterparts in the key set were analyzed with x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy by Lisha Glinsman at the National Gallery to ensure positive identification of the predominant metallic elements present in each print (Glinsman and McCabe 1995). The prints were then visually examined, compared, and discussed by the assembled curators, conservators, and historians, and the following observations were made:

To illustrate the effects of some known treatments for discoloration of platinum and palladium photographs, a series of experimental samples were presented at the colloquy by Constance McCabe, consulting photograph conservator at the National Gallery of Art (McCabe 1993). Sample prints had been fabricated and aged, several different treatment protocols applied, and the treated prints re-aged. Results indicated that the commonly recommended technique of reclearing discolored prints in hydrochloric acid had little effect, but a calcium hypochlorite bleach reduced discoloration noticeably. McCabe's study illuminates the possibilities for Steichen's treatment and invites some tentative explanations for the observations that were made about the original photographs. It may be that when examining the prints for distribution of the collection in the late 1940s, Georgia O'Keeffe, an accomplished painter and colorist, determined that many of them seemed darker and yellower than when first made. This finding induced her to contact Steichen, who treated the prints chemically, perhaps with a calcium hypochlorite bleach or equivalent. Original surface coatings and retouching may have been removed by the treatment and in some cases reapplied by Steichen. If this scenario of events 40 years ago is accepted as likely, then current custodians of these prints should be well aware of their unique history. They may have a heightened susceptibility to physical deterioration, such as surface cracking or weakening of the paper support, and the utmost care should be exercised in handling, housing, and exhibiting them. 7 CONCLUSIONSThe undocumented treatment of this significant body of work presents an intriguing puzzle to conservators, curators, and historians alike. It may never be solved. It is always possible that a reliable written record of the treatment exists, but the probability of locating such a document is dwindling. It is also possible that some analytical technique that does not require unacceptable sampling of originals will be found to solve the riddle. But at present we can only gather the clues available in existing sources and offer informed speculation. While one print suffered measurable change during one exhibition, subsequent monitoring of similar prints on exhibit has shown no reoccurrence

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSI would like to specially thank Constance McCabe and Nancy Reinhold for their key contributions to this research. Thanks also to Roy Perkinson, Nora Kennedy, Jill Sterrett, and Sarah Greenough for sharing insights about the Stieglitz prints in their collections, and to Sylvia Wolf for her critical review of this manuscript. Finally, I want to publicly express my appreciation to Doris Bry, who has been extremely generous to me with her time and her recollections. REFERENCESBry, D.1965. Alfred Stieglitz: Photographer. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. Bry, D.1993–94. Personal communications. New York, N.Y. Crawford, W.1979. The keepers of light. Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Morgan and Morgan. Eisler, B.1991. O'Keeffe and Stieglitz. New York: Doubleday. Emerson, P. H.1899. Naturalistic photography for students of the art, 3d ed.London: Dawbarn and Ward. Glinsman, L., and C.McCabe. 1995. Understanding Alfred Stieglitz's platinum and palladium prints: Examination by x-ray fluorescence spectrometry. In Conservation Research, Studies in the History of Art, vol. 51, Monograph Series II. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. Gottlieb, A.1993. Chemistry and conservation of platinum and palladium photographs. Senior thesis. Princeton University, Princeton, N.J. Gottlieb, A.1995. Chemistry and conservation of platinum and palladium photographs. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation34:11–32. Greenough, S.1973. The published writings of Alfred Stieglitz. Master's thesis, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, N.M.

Greenough, S.1992. Stieglitz in the darkroom. Exhibition brochure. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. McCabe, C.1993. Reclearing treatments used for aged facsimile palladium prints. Unpublished report for Curatorial/Conservation Colloquy V: Alfred Stieglitz's Palladium Portraits of Georgia O'Keeffe. National Gallery of Art, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Washington, D.C. Nadeau, L.1986. History and practice of platinum printing, 2d rev. ed.Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada: published by the author. O'Keeffe, G.1949. Stieglitz: His pictures collected him. New York Times Magazine, December 11, 24–30. O'Keeffe, G.1950. Letter to Daniel Catton Rich. January 30. Archives of the Art Institute of Chicago. Reinhold, N.1991. An investigation of the aging of platinum and palladium photographs. Unpublished report. Art Institute of Chicago. Severson, D.1986. The effects of exhibition on photographs. Topics in Photographic Preservation1:38–42. Steichen, E.1963. A life in photography. New York: Doubleday. Stieglitz, A. [1898] 1905. Platinum printing. In Picture taking and picture making. Rochester, N.Y.: Eastman Kodak Co. Reprinted In The modern way of picture making. Rochester, N.Y.: Eastman Kodak Co., 1905. 122–28. Stieglitz, A.1934. Alfred Stieglitz: Exhibition of photographs. Exhibition brochure. New York: An American Place. Thompson, J.1993. Processes and techniques used by Stieglitz, 1886–1940. Unpublished chronology. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Wilhelm, H.1981. Monitoring the fading and staining of color photographic prints. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation21:49–64. Willis, W.1880. Improved materials and processes for photochemical printing. British Patent #1117. Reprinted in Nadeau 1986. FURTHER READINGAlfred Stieglitz Archive, Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Danzing, R.1990. Alfred Stieglitz: Photographic processes and related conservation issues. Topics in Photographic Preservation4:57–79. Greenough, S., and J.Hamilton. 1983. Alfred Stieglitz: Photographs and writings. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. Lowe, S. D.1983. Alfred Stieglitz: A memoir/biography. London: Quartet/Orl Books. Stieglitz, A.1978. Georgia O'Keeffe: A portrait. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Ware, M.1986. An investigation of platinum and palladium printing. Journal of Photographic Science34:13–25. AUTHOR INFORMATIONDOUGLAS G. SEVERSON has been the conservator of photographs at the Art Institute of Chicago since 1981. He holds an M.S. in photography from the Institute of Design at Illinois Institute of Technology and an M.F.A. in photography from Rochester Institute for Conservation Photographic Materials Group. Address: Photography Collection, Art Institute of Chicago, Michigan Ave. at Adams St., Chicago, Ill. 60603.

Section Index Section Index |