PRESERVATION OF 19TH-CENTURY NEGATIVES IN THE NATIONAL ARCHIVESCONSTANCE McCABE

6 PRESERVATION OF COLLODION NEGATIVESBASED ON an understanding of the collodion negative's component materials, causes of deterioration, and research needs, the National Archives developed a large scale program to care for its 19th-century negatives. The primary preservation objectives involved in this project are: cleaning the negatives, removing tape from them as appropriate, duplicating them, rehousing them, and storing them in appropriate cabinets and facilites. Instructions for those engaged in the project are:

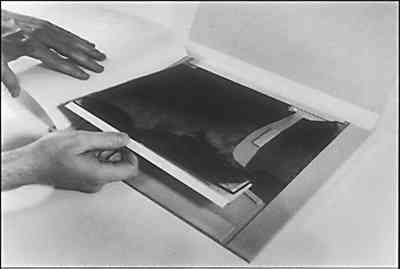

6.1 CLEANINGThe image side of a collodion plate is extremely sensitive to moisture and to organic solvents. Despite claims that collodion negatives may be safely cleaned (Ostroff 1976; Rempel 1987, 84),7 tests carried out at the National Archives indicate that damage is likely to result from attempting to clean tha image side of the plate with water based on with most organic solvent-based cleaners. Washing collodion plates can be very damaging and should not be attempted. Because of the collodion negative's sensitivity to cleaning, only a soft-hair brush may be used to dust the image side of the plates and only when the condition of the plates (no flaking or softening) allows for safe dusting. Surface dirt on the nonimage glass side, if not cleaned away, will be visible in duplicate negatives. Concern has been expressed, however, about the possibility of accelerating deterioration of the glass by the use of cleaning solutions on the glass side of the plate (Moser 1961; Simpson 1959). Tests were made to determine if cleaning the glass side would be safe and, if so, to select a cleaning solvent. A range of solvents, including commercially available glass cleaners, water, alcohol, acetone, and acidic and alkaline aqueous solutions, were tested on both deteriorated 19th-century glass and on modern, comparatively stable, window glass. Samples were aged in a cycling oven (room temperature and RH to 50�C and 95% RH daily for 15 and 30 days). Deterioration was induced in all samples, with more severe deterioration seen consistently in all 19th-century samples. No cleaning solution was isolated as superior, and no cleaning solution performed noticeably better than water. Despite inconclusive test results, a decision was made to clean all nonimage glass surfaces of the negatives with detonized water, since a primary preservation goal is to create duplicates of the highest possible quality with the greatest amount of retained information. Such duplicates can be produced only with negatives that are as clean as possible. By retiring the originals from use and storing them in an environmentally controlled area, it is hoped that further deterioration of the plates will be arrested. In this way the best balance between preservation and the needs of researchers can be achieved. 6.2 TAPE REMOVALBefore these negatives were acquired by the National Archives, a number of broken plates were mended with verious adhesive tapes. Some of these mends apparently date from the 19th century and employed gummed paper tape. Twentieth-century tapes included pressure-sensitive cellophane tapes and several types of opaque masking tapes. Fortunately, only a few plates had adhesive applied to their image side. In order to reproduce as such image information as possible from these taped plates, uninscribed mending tape was removed from the glass side. No labels, masks, tapes, or attachments with potentially historical significance were removed, however, nor were any other original elements of the artifact removed, such as retouching or other unusual components of the negatives. Tape removal was carried out with great care, as this operation usually required manipulation of the plates while placed face down on smooth paper. For plates with binder or varnish deterioration, the edge of the glass was supported while the tape was removed. The procedure for tape removal involved first cutting the tape along the edges of breaks. Once the plate was separated into individual pieces, the tape was mechanically peeled or scraped away. Residual adhesive was removed with an appropriate solvent such as water, ethanol, or acetone, applied locally with a cotton swab. Care was exercised to avoid contact of the solvent with the image side of the plate, since the binder and varnish layers are often readily soluble. Because of this solubility, special care was taken with plates containing tape on the image side. Where the carrier and adhesive of the tapes could be removed from the image side mechanically and without the use of solvents, the tape was removed. More tenacious tapes on the image side have not yet been removed. Problems related to reversibility and optical properties of adhesive repairs of glass have resulted in the decision to assemble the broken negatives in their proper orientation during the duplication step and not to repair them. Adhesives presently employed to repair glass objects are primarily organic polymers, including synthetic polyester, epoxy, polyvinyl alcohol and acrylic resins, and cellulose nitrate. Silicones and silance are also used in glass conservation. However, if a collodion negative were repaired with any of these adhesives and it became necessary to reverse the adhesive, it would be diffcult to do so. Capillary action of liquids between glass joints is difficult to control while applying adhesives or solvents and could threaten to dissolve the image bearing layer. Therefore, rather than repairing the broken negatives, they have been rehoused as described below. 6.3 DUPLICATIONThe image in 19th-century negatives differs significantly from most modern film negatives. They were made to be printed onto a printing-out paper such as albumen paper (Reilly 1979). Negatives used in printing-out systems are exposed in direct contact with the photographic paper. The printing out paper darkens spontaneously when exposed to light, creating a print the same size as the original negative. The negatives employed for the printing-out process are longer in tonal range and often higher in contrast than are most modern film negatives. The characteristics of 19th-century negatives make them capable of producing excellent printed-out prints. Difficulties are encountered, however, when these negatives are printed onto modern developing-out papers. Modern developing-out papers require chemical development to produce an image. When 10th century negatives are printed onto developing-out papers, image detail is often sacrificed. The negatives required for use with developing-out papers have a relatively short tonal range, but because modern negatives and photographic papers have been manufactured to be used together, the results can be comparable to the excellent image quality of printing-out systems. In order to produce prints that retain maximum image quality, a two-step interpositive-duplicate negative system was selected to preserve these negatives photographically (Munson 1982). This two-step process produces two sets of images from the original glass plate: interpositives and duplicate negatives. First, two interpositives are made by contact printing the negative onto film. One sheet is exposed to reproduce all highlight, middle tone, and shadow detail, matching the entire tonal range of the original plates (fig. 33). Another sheet is then exposed to create a positive “shadow mask,” which is a high-contrast rendering of only the shadow detail (fig. 34). The shadow mask is required to create a duplicate negative of complete tonal range and to compensate for factors related to modern film manufacture, exposure, and processing. After processing, these two interpositives are placed in register, and, as the name indicates, the image appears as a positive. These two interpositives are then exposed in register onto another sheet of film. With this system, a duplicate negative of extremely high quality is created (fig. 35).

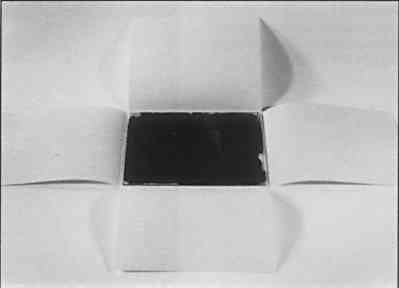

After being processed according to archival specifications, inspected for quality, and jacketed, the interpositives are segregated from the duplicate negatives. The duplicate negatives are stored in the stack area and used by the photographic laboratory as prints are requested. For archival security, the interpositives are stored separately. The interpositives are considered the archival record and are used only when another duplicate negative is needed. The original plates are retired from use. 6.4 REHOUSINGPhotographic negatives must be housed in enclosures that will protect them from physical and chemical damage. For these glass negatives, two types of storage systems have been designed, based on their condition. For plates in good condition, a vertical storage system is used. Plates in poor condition—with flaking, lifting, or softening of the binder of varnish layers of breakage of the glass support—are stored horizontally and protected individually with paper enclosures. The paper enclosures used in this project had to meet rigid specifications to ensure the suitability of the papers and adhesives for housing collodion negatives. Analytical tests were conducted to determine pH, alkaline reserve, reducible sulfur and lignin content, and sizing agent used. Accelerated aging was carried out with modern photographic materials incubated in contact with storage enclosure materials to further aid in the selection of proper storage materials (ANSI 1986). Seamless four-flap paper enclosures have been produce in various standard sizes for the storage of plates in good condition. These enclosures allow the user safe access to the plate by unfolding the flaps rather than by sliding it out of the sleeve while grasping it between finger and thumb. Because deterioration of silver images has been associated with adhesive seams, no adhesive has been used to fabricate these enclosures. It is hoped that these four-flap enclosures will prevent image deterioration associated with adhesive seams (fig. 36).

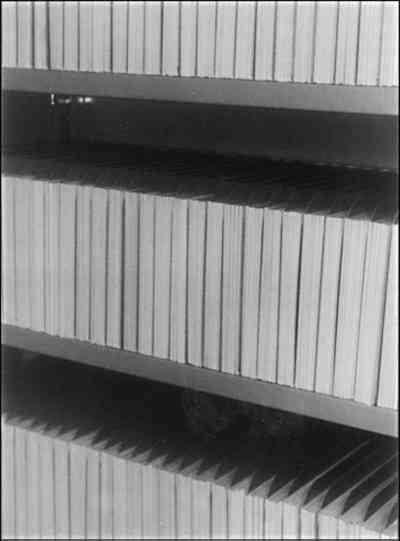

These enclosures are used for plates of standard size, plates slightly smaller than the closest standard size, and those with small corner or edge losses. A sheet of thin rigid paperboard the full size of the enclosure is inserted for additional support for those plates that are smaller than the size of the enclosure. Negatives in good condition are stored vertically, on the longer plate edge, on shelves with metal dividers the full size of the plates. Four to five plates are stored between each pair of dividers (fig. 37).

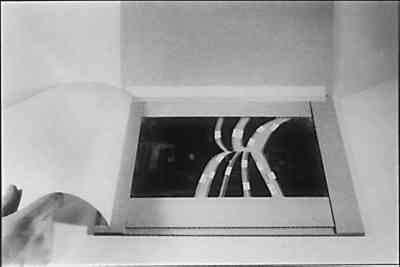

Sink mats have been constructed in several standard outer dimensions for the protection of damaged negatives. These enclosures are made of high-quality materials, including corrugated paperboard, mat board, and smooth bond-weight paper, with acrylic pressure-sensitive tapes used for assembly. Care is taken to assure that no adhesive is applied near the plate. These sink mats are designed to give rigid horizontal support. The high-quality corrugated paperboard cover does not come in contact with the image side of the negative because the walls of the sink mat are built slightly higher than the thickness of the plate within and a paper interleaf is placed between the plate and the sink mat cover. If a negative exhibits softened of flaking binder and varnish layers, the interleaf is attached to the inside cover with adhesive and the sink mat is constructed with extra wall height, thus preventing contact of the enclosure with the vulnerable negative. The broken negatives are assembled in proper orientation for duplication but are housed in sink mats with the components separated with paperboard spacers attached with adhesives to avoid mechanical damage to the glass pieces (figs. 38–39). Each problem plate requires individual attention; its enclosure is constructed to meet its special needs, and each sink mat is custom made.

Negatives housed in sink mats are stored horizontally in stacks of three to six (depending on size and weight) within storage boxes. Boxes are of the drop-front style with metal stays. If safe to do so, two or three boxes may be stacked on each shelf. Each box is marked with the cautionary label, “Coution: Broken Glass. Carry Horizontally” (fig. 40).

A decision was made not to seal broken or flaking negatives within a glass “sandwich” as this kind of protective package, where the glass is tightly enclosed, can produce corrosion in chemically unstable glass (Barger et al. 1989). To avoid the possibility of accelarated deterioration of a glass negative within such an enclosure, unstable plates are enclosed in paper sink mats. 6.5 STORAGEThe preservation of archival records demands that everything meant to protect them be selected cautiously. Not only must the materials that come in close contact with records be of the highest possible quality, but the larger environment must also be regulated to ensure the preservation of permanently valuable holdings. Because of the fragility of these glass plates, and their sensitivity to the environment the stall at the National Archives developed detailed specifications not only for storage enclosures, but for storage cabinets, materials used to renovate the storage room, for fire suppression, and air quality. A major concern was the choice of available paint finishes for storage cabinets. Environmental contaminants, such as volatiles associated with inadequately cured alkyd oil-base paints, have been showen to cause silver image delertoration (Feldman 1981), Steel cabinets finished with baked enamel have long been recommended for storage of photographic materials, since it is commonly believed that the baking process ensures thorough curing of the finish and always eliminates potentially harmful paint volatiles, such as peroxides and organic solvents (Time-Life Books 1972). Thus steel cabinets with a baked enamel finish were custom made for this project. The National Archives had difficulty procuring a type of cabinet with a paint finish that met its specifications. Cabinets in the first shipment arrived with a strong odor of paint solvents indicative of inadequate curing during the baking process. As specifications limited the allowable valatiles, the cabinets were sent back of the manufacturer to be rebaked. This experience alerted the Archives to the possibility of improper curing procedures during the manufacture of painted cabinets. It is critical that the baking process eliminate potentially damaging volatiles and that measures be taken to ensure thorough curing of paint finishes. There is need for further testing of paint films to determine their sultability for storage of archival records. At this time, the Archives is investigating other finishes, such as powder coating, for future use with photographic materials and other permanently valuable records. Two basic cabinet designs have been fabricated, one for horizontal storage and the other for vertical storage. In the vertical storage cabinets full-size rigid dividers are placed at 1 inch intervals. Each space can accommodate several negatives, and each shelf up to 100 plates. Depending on the size of the plates, and the number and sizes of plates to be placed on each shelf, different weight load specifications were required. All cabinets are constructed with locking doors, and six air vents provide for ventilation. The doors and venta of the cableneta are sealed with allcome rubber gaskets. The seals provide assurance that, in case of ceiling leaks, water will not seep into the cabinets Locking devices and shelf brackets are nickel plated. A room was specially renovated for the storage of photographic holdings of high intrinsic value, including these 19th-century negatives. The room has been equipped with a self-contained air-conditioning system that filters and purifies the air and controls the temperature and relative humidity (65�F and 35%–40% RH). Fluorescent light fixtures are equipped with ultraviolet filters. Fire suppressant systems include Halon (a cholorofluorocarbon) with a dry pipe water extinguishing backup. The National Archives is eagerly awaiting development of an environmentally safe substitute for Halon that meets the standards described in the Montreal Accord, an international agreement that will prohibit the use of halogenated hydrocarbons that adversely effect the ozone layer. The walls, cellings, and fixtures in the photographic storage room have been finished with water based latex acrylic paint, and the floor is covered with a nylon carpet. Since no carpet padding was commercially available that met the Archives's requirements for chemical inertness, none was used. The seams of the carpet were attached with a silicone heat seal, and the carpet was tacked to the concrete floor with concrete nails. |