THE IN-SITU CONSERVATION TREATMENT OF A NINETEENTH-CENTURY FRENCH SCENIC WALLPAPER: LES PAYSAGES DE T�L�MAQUE DANS L'ILE DE CALYPSODoris A. Hamburg

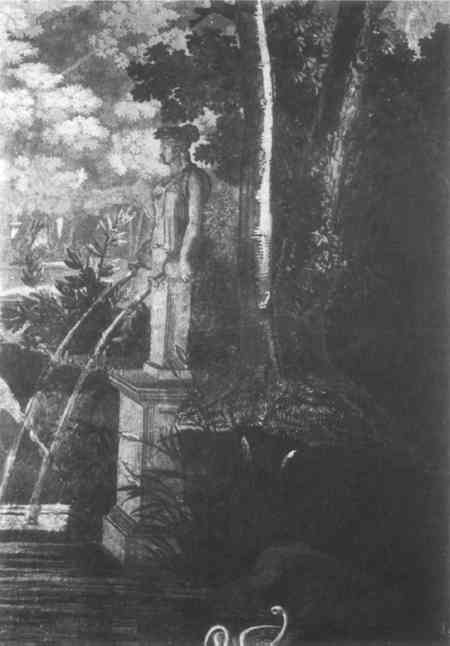

ABSTRACT—A conservation project to preserve the Dufour French scenic wallpaper Les Paysages de T�l�maque dans l'�le de Calypso was undertaken in situ at the Hermitage, President Andrew Jackson's home near Nashville, Tennessee. Historical background to the early nineteenth-century wallpaper is given, as well as an explanation of the treatment undertaken to clean, consolidate pigments and paper supports, and inpaint the deteriorated wallpaper. Stabilization of the environmental conditions was effected in coordination with the wallpaper treatment. 1 INTRODUCTIONIN 1836 PRESIDENT ANDREW JACKSON (1767–1845) purchased the French scenic wallpaper Les Paysages de T�l�maque dans l'�le de Calypso1 to decorate the grand stair-central hallway of his Tennessee home the Hermitage. The wallpaper remains in place today, providing a vivid link to the history of the house and its owner as well as an example of nineteenth-century decor and taste. The wallpaper was the subject of a major preservation effort during the summers of 1978 and 1979.2, 3 The Hermitage retains the original floor plan typical of many large Southern homes. A long and wide grand hallway (54 feet by 11 feet) served as entry way, reception room, and occasional ballroom. Doors at the north and south ends, when opened, allowed for cross-ventilating breezes. To the sides of the central hallway are the parlor and bedrooms. The winding stairway leads to the second floor and more bedrooms. 2 LES PAYSAGES DE T�L�MAQUEThe distinctive scenic wallpaper Les Paysages de T�l�maque was designed between 1815 and 1820 by Xavier Mader for the French wallpaper firm of Joseph Dufour.4 Adapted from a philosophical tale written in 1699 by Francois F�nelon (1651–1715), the paper depicts the mythological adventures of Telemachus searching for his father Ulysses. Twenty-five panels, approximately 21 inches wide by 7 feet high,5 comprise the narrative cycle illustrating Telemachus' stay on the island of Calypso. The panels are hung one adjacent to the next, giving the appearance of a unified panorama. Upon closer examination, however, the various chapters become evident as the same characters reappear in different scenes, e.g., Telemachus is always shown wearing a red cloak over a white toga. The wallpaper was elaborately designed and executed. In manufacture the paper was first brushed overall with a light blue paint, probably having a hide glue binder. The images were then built up with vivid colors transferred by numerous woodblocks to the paper; 2,027 different blocks with 85 colors were used to print the Telemachus wallpaper cycle.6 More than one edition of the Telemachus cycle were printed, and dating is difficult. The Dufour business and blocks were sold several times during the nineteenth century. For early impressions, rectangles of laid paper, approximately 18 inches by 22 inches, were pasted together to make long panels ready for printing. At an unspecified later date the design was printed onto continuous roll paper. This change in manufacturing process is very noticeable at the Hermitage: the East Wall design is printed on small sheets, whereas the West Wall design is printed on long, continuous roll paper. Fiber analysis indicated that the laid paper on the East Wall is composed mostly of linen fibers with some cotton, a mixture typical for paper prior to the mid-nineteenth century. Analysis of the West Wall's continuous roll paper revealed rag fibers with an admixture of groundwood or straw. This combination did not appear until after 1850.7 Pigment analysis offered no conclusive evidence in dating the Hermitage wallpaper. The circumstances of installation of the paper currently on the West Wall are uncertain. It presumably replaced an earlier paper of the East Wall vintage. In the central hallway the full Telemachus cycle is shown one and one-half times. Under the stairs, it is apparent how the leftover panels were pieced to fit an awkward space. 3 HISTORY OF PRESERVATIONAs indicated above, the central hallway extends the full depth of the house with doors at either end. Tour visitors continued to use these doors regularly until 1978. Over the many years fluctuations in humidity and temperature caused severe deterioration in the condition of the friable paints and paper. There were also some leaks in the ceiling. Photographs from the end of the nineteenth century depict the already deteriorated condition of the paper, with portions detached and flapping in the breeze. Visitors have often touched the wallpaper as well as taken souvenirs. The stair area particularly suffered from abrasion due to visitors passing against the wall. Documentation regarding early care of the wallpaper is minimal. Throughout the years several people have retouched deteriorated areas. In 1930 James B. Wilson directed the removal of the paper from the walls, at which time it was lined with a wood pulp paper secondary support and then canvas and reattached to the walls. A cross-section of the layers would reveal plaster wall, canvas backing, secondary backing support, original primary support printed image, and/or overpaint. In an effort to reduce abrasion damage to the wallpaper, non-glare plexiglas was installed following structural restoration of the mansion in 1971. However because the plexiglas was installed directly against the paper (omitting an air space for proper air circulation), condensation, waterstaining and mold growth on the paper resulted. The plexiglas was removed and upon examination in 1978 the plaster was found to be dry and the mold no longer active. The Telemachus wallpaper has suffered substantially over the years. In choosing the most appropriate action for preserving the hallway's appearance, reproduction of the wallpaper or removal of the paper for treatment would have proven too costly and impractical. After discussion among curators and conservators,8 it was decided to treat the Telemachus wallpaper in situ. The dado, which is thought to have been installed since Jackson's death, was not to be treated as little original paint remains following a complete overpainting in the 1960's. 4 CONDITIONThe first task at the Hermitage was to prepare a detailed condition evaluation, which provided both the necessary familiarity with the wallpaper as a physical material and an in-depth knowledge of its problems. Major design areas of each Telemachus panel were outlined and diagrammed according to various types of deterioration: tears, losses and cleavage in the paper supports, cracks in the plaster walls, flaking paint and overpaint. Tears and complete loss of primary support were found throughout the hallway. Panel edges were often lifting and there was blind cleavage between the supports and wall. The latter could be detected by lightly tapping suspect areas. The binder in the paint had deteriorated and the paint proved very friable. Paint was flaking in major portions, both in original and restoration paints. The sky was particularly abraded. The distinction between original block-printed areas and later painted additions is readily visible in normal and ultraviolet lights. Previous inpainting and overpainting was considerable in some panels. Discernible evidence of several different artists' work indicates that some of the early restoration painting was quite competently executed, even if a little creative in design. Painting in other areas was sloppy, irreversible and ill-matched, even given the possibility that colors have altered with time. The restoration media appeared to include poster paints, tempera and casein. Along with the diagrams, black-and-white 35 mm photographs were taken of each section of the walls, as were 35 mm color slides for detail views. 5 TREATMENTThe treatment involved several main steps which might be broadly categorized as cleaning, consolidation, filling and inpainting. Paper and canvas which covered cracks in the plaster were peeled back to expose the crack and lightly secured with masking tape. In some areas it was necessary to cut carefully through the paper and canvas to reveal the entire crack. A professional plasterer repaired the wall cracks. Thereafter the canvas, secondary support and original paper were readhered using wheat starch/methyl cellulose paste with thymol fungicide. In some areas a small amount of poly (vinyl acetate) emulsion Jade 4039 was added to the paste for extra strength. Cleaning followed. Loose surface dirt was minimal except in a few areas which were lightly cleaned using a soft brush. Testing revealed that only the poster-paint variety of overpaint could be removed safely from the wallpaper and this had to be accomplished before consolidation of the paint. Gentle rolling with cotton swabs dipped in distilled water, to which a fractional percentage of wetting agent10 had been added, removed much of this paint. Parts of the original design that the overpaint had hidden became evident. In many areas, however, removal of the restoration paint revealed large areas of abrasion in which no original paint remained. The West Wall continuous roll paper was more reactive to water than the earlier vintage East Wall paper. More tenacious paint had to be left on the West Wall rather than endanger the original paint and primary support. The West Wall was also swabbed with heptane, an organic solvent, to remove surface grime and aid later penetration of the consolidants.

Consolidation proceeded in two steps. First the water sensitive paint layers were relaxed and lightly reattached to the paper by the application of a solution of 2% methyl cellulose in distilled water. This was applied with one-inch watercolor brushes. On the East Wall the application was followed by a soft three-inch brayer rolled over paper towelling against the wall to absorb the excess moisture and to apply gentle pressure. It was found that this process cleaned the paper somewhat as evidenced by the dirt on the paper towels and a generally brightened appearance. On the West Wall it proved unsatisfactory to roll over the paint through the towelling due to a higher reactivity to water and weak adhesion between wallpaper and paint. Paint flakes would adhere to the towel, however gently it was applied. Thus in order to remove excess methyl cellulose from the West Wall, each area upon drying was gently swabbed with cotton dipped in 1:1 ethanol/distilled water. At this point, a second adhesive, 5% v/v poly (vinyl acetate) resin AYAA in toluene was applied by brush overall, with the exception of the sky, to provide a stronger bond and to counteract the effects of humidity. Due to the toxicity of toluene the application was done in the evening, when visitors and staff had gone home. Fans were in operation and the conservators wore respirator masks. During the second summer, ethanol was available as the solvent for PVA AYAA, which reduced the toxicity problem. In some areas the use of low heat, provided by a tacking iron through silicon release paper, aided adhesion in severely flaking areas, as did a second coat of PVA AYAA in other sections. In the sky portion of the design it was noted that some color intensification resulted from application of PVA AYAA. Therefore during the first summer, the sky was consolidated only with methyl cellulose. Re-examination of the sky section during the second summer indicated, however, that consolidation with only methyl cellulose was insufficient. Also, that area was extremely difficult to inpaint due to its continued reactivity to water. Further testing showed that after consolidation with the AYAA the hue and intensity better approximated other areas of original paint and blended more satisfactorily with the blue paper border above the sky. After curatorial and conservation discussion, it was decided to consolidate the sky throughout the wallpaper, brush-coating it with the 5% v/v poly (vinyl acetate) resin AYAA. To attach cleaving paper, wheat starch/methyl cellulose paste was introduced with a syringe or brush as appropriate. The paper was then held in place briefly or rolled over with a brayer on a paper towel. Losses in the primary support paper, where inpainting would be required, were filled with Permalife acid-free bond paper attached with the wheat starch/methyl cellulose paste. Inpainting was the most time-consuming aspect of the treatment. A cosmetic procedure, the inpainting was geared to the general restoration of the original design. An essential aid in evaluating the images was a set of color photographs of another example of the Telemachus wallpaper. The wallpaper used as a reference is in excellent condition.11 The colors of the reference set, as shown in the photos, were somewhat different from those at the Hermitage, so inpainting colors were determined through a comparison of related areas of the original on the Hermitage wallpaper. Liquitex acrylic polymer emulsion paints were used to inpaint the areas of

Working on site involved logistical considerations in planning the treatment; throughout both summers of the conservation work visitors continued to tour the central hallway as it was the only access to the parlor and the main staircase. Scaffold and equipment added to the disruption. Via a poster, guides' explanations and personal conversations, a concerted effort was made to thwart the myriad conclusions arrived at by the visitors regarding the unfamiliar activity in the central hallway. The scale of such a wallpaper project must not be underestimated; by the completion of the treatment the more than 580 square feet of wallpaper had been covered seven different times, rarely using any tool larger than a one-inch brush. 6 FUTURE PRESERVATIONTo insure preservation of the treated wallpaper, it was necessary to curtail fluctuation of the relative humidity levels in the house. In 1978 air conditioning was installed to help regulate temperature and humidity. Visitors have been rerouted in order to keep the exterior doors to the central hallway closed at all times. Plexiglas panels, spaced one half inch from the wall for air circulation, were reinstalled at the sides of doorways and along the stairs to avoid wall abrasion by visitors. Future periodic evaluations of the wallpaper's condition are warranted. 7 CONCLUSIONThe conservation treatment—cleaning, consolidating paint, and reattaching paper supports—stabilized the deteriorated wallpaper. Inpainting helped to recall the original vivid appearance of the lively adventures of Telemachus. Fundamental to this treatment was the stabilization of the wallpaper's environment—through air conditioning, visitor rerouting, and protection against abrasion through a few strategic plexiglas panels. While a very major project, this preservation effort made possible the continued appreciation of a valued artifact of nineteenth-century history and culture. FOOTNOTES

A manuscript bill in the Jackson papers, Hermitage, TN 1/2/1836 indicates that the President first ordered three sets of the Telemachus wallpaper in 1836 from George W. South of Philadelphia at $40 per set. As the shipment was not received, a second order was placed with Robert Golder of Philadelphia, whose billing price was $29 per set (bill 10/25/1836). The variation in price is not understood at this time. (Catherine Lynn, Wallpaper in America (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1980), pp. 225, 505.) The treatment proposal was designed by Anne F. Clapp, Print and Paper Conservator, Winterthur Museum. Treatment was carried out by Elizabeth H. Court, Doris A. Hamburg, Kristin Hoermann, Debbie Hess Norris, and Lois Olcott Price, with assistance from Christine King Young, Graduate Fellows in the Winterthur/University of Delaware Art Conservation Program. Mildred B. McGehee, formerly Curator, the Hermitage, coordinated the project for the Ladies' Hermitage Association. Miss Clapp provided the fiber analysis and Donald K. Sebera, Conservation Scientist, Winterthur/University of Delaware Art Conservation Program analyzed the casein paint. An earlier discussion of this project appeared in: Lois OlcottPrice and Elizabeth KaiserSchulte, “Conserving the Paper Stainers' Art: The In Situ Treatment of Two Historic Wallpapers,” Art Conservation Training Programs Conference (Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, 1979), pp. 5–24. Lynn, Wallpaper, in America, pp. 503–4. When printed the scenic wallpapers generally measured eight to ten feet high. Often they were trimmed at the top, in the sky area, to accomodate the dimensions or interior decor of the room. A light blue border currently hangs over the Telemachus wallpaper; it appears to have been installed when the wallpaper was treated in1930. Paris, Mus�e des Art Decoratifs, Trois Si�cles de Papiers Peints (Paris: Mus�e des Arts Decoratifs, 1967), p. 47. Grant, Julius, Books and Documents: Dating, Permanence and Preservation (London: Grafton & Co., 1937), p. 16. In addition to the conservators mentioned above, Caroline Keck, Professor, Cooperstown Graduate Programs, and Marilyn Kemp Weidner, currently Director, Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts, provided early assistance to the Hermitage in this project. Sources for the materials were as follows: poly (vinyl acetate) emulsion Jade 403 obtained from TALAS, 140 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10011; poly (vinyl acetate) resin AYAA (beads) manufactured by Union Carbide Corporation, Chemicals & Plastics Division, 270 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017; Methyl Cellulose Paste Powder marketed by Process Materials Corporation, 301 Veterans Boulevard, Rutherford, NJ 07070; Permalife paper obtained from Conservation Resources International, Inc., 1111 North Royal St., Alexandria, VA 22314; Liquitex acrylic polymer emulsion artists' colors marketed by Permanent Pigments, Inc., Cincinnati, OH 45212, available in artist supply stores. A drop of Igepal CO-630 or Kodak Photo Flo 200 was added to approximately 300 ml distilled water. Occasionally a drop of ammonia was substituted for the wetting agent. Igepal is available from TALAS, 140 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10011, and Kodak Photo Flo may be purchased in photo-supply stores. This example of the Telemachus wallpaper is owned by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, Boston, MA.

Section Index Section Index |