WALLPAPER AND ITS CONSERVATION—AN ARCHITECTURAL CONSERVATOR'S PERSPECTIVEAndrea M. Gilmore

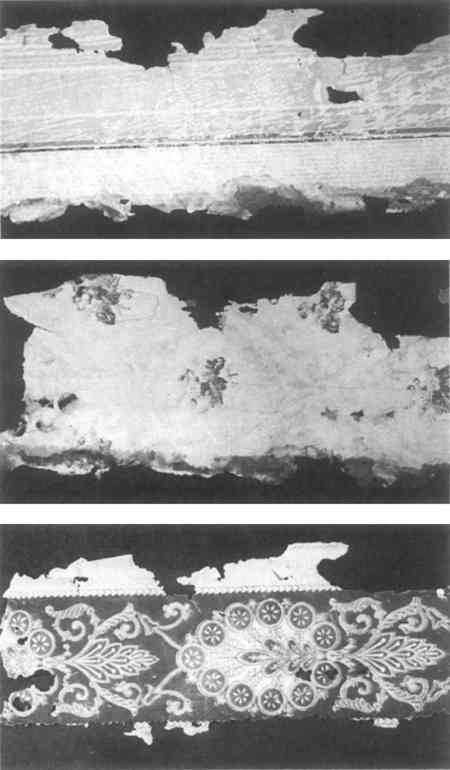

3 CONSERVATION OF SMALL WALLPAPER FRAGMENTSSmall fragments of wallpaper are conserved primarily for documentary purposes—both in situ and in reference collections. The architectural conservator uses these samples to document alterations that have been made to interior rooms and as a basis for reproduction wallpapers. The size of small wallpaper samples enables the wallpaper conservator to treat the sample as a more isolated artifact. The level of collaboration required between the architectural conservator, historic building curator, and wallpaper conservator is greatly reduced. The small fragments of wallpaper found in a historic structure can provide an architectural conservator with a wealth of information, as illustrated by the three layers of wallpaper found when a door casing was removed from a first floor room at Lindenwald (see Figure 4). This information clarified what the original use of the room had been. Two uses had been claimed for the room—one a bedroom, the other a

The three layers of wallpaper found under the door casing also confirmed that this exterior door was a later alteration. Since the room was built in 1850 and the kitchen moved into it some time during the late part of the nineteenth century, the addition of the exterior door probably coincided with this use change. The presence of the wallpapers under the door casing further indicated that the ceiling and plaster cornice of the room had not been painted originally. Comparison of paint samples from the plaster walls and the ceiling showed that they contained the same sequence of paint layers. The wallpapers found under the casing clearly indicated that the walls had been unpainted originally, indicating that the ceiling and plaster cornice had been unpainted originally as well. Since this room will be returned to its c. 1850 appearance, the room will be restored as a bedroom. This will entail removing the later exterior door and filling the opening. The three layers of wallpaper found under the casing will be removed and stored in the Park's historic wallpaper collection. The sample of the pink striped wallpaper, layer No. 1, will serve as the basis for a reproduction wallpaper to be used in the bedroom. Conservation of these samples involving cleaning, photographing, encapsulating in mylar and labeling. In the realm of wallpaper conservation, samples conserved for reference collections come the closest to isolated objects for purposes of treatment. Distinguishing characteristics of the wallpaper samples are also recorded on a standardized form (see Appendix A). At the Antram-Gray House at the Roger Williams National Memorial in Providence, Rhode Island, early nineteenth century wallpapers also proved valuable in documenting the evolution of the house. In a small room on the second floor, removal of a baseboard revealed a wallpaper with a border. The border of the wallpaper outlined an earlier set of stairs (see Figure 5). The Antram-Gray House, unlike Lindenwald, will not be restored to a specific period. Rather, the intent is to preserve, in situ, as much of the historic fabric as possible. The sample will require some cleaning, readhering and protection from abrasion after conservation. As with the conservation of entire rooms of wallpaper, measures should be taken to minimize the physical or environmental conditions that might cause damage to the wallpaper. In situ conservation of a small fragment of wallpaper, like the sample at the Antram-Gray House, requires limited interaction between the architectural conservator and wallpaper conservator.

|