WALLPAPER AND ITS CONSERVATION—AN ARCHITECTURAL CONSERVATOR'S PERSPECTIVEAndrea M. Gilmore

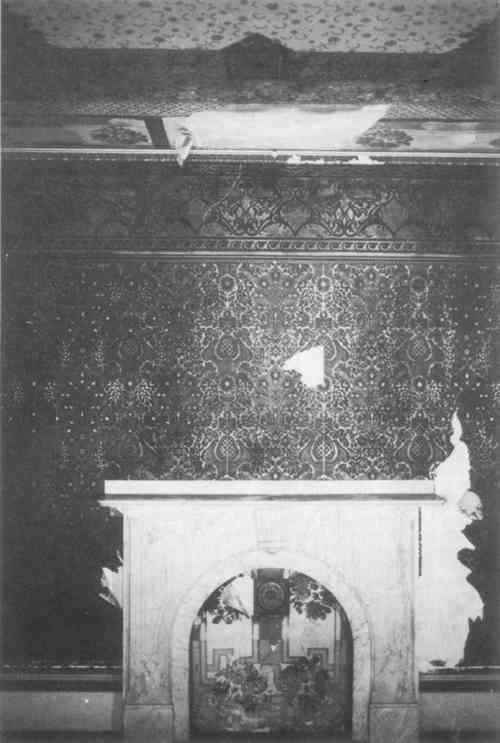

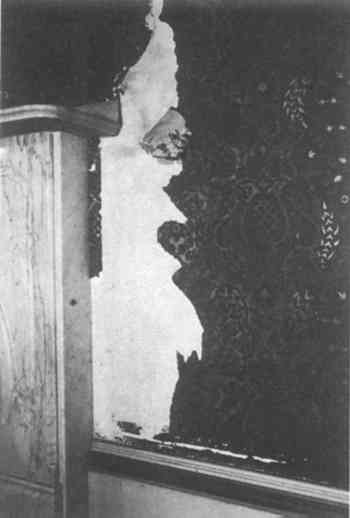

ABSTRACT—A discussion of the objectives and role of the architectural conservator in the task of wallpaper conservation. The interdependent relationship of the historic wallpaper and the structure in which it hangs is described. Criteria for determining appropriate conservation treatments are listed, noting especially the biases of architectural conservators towards various types of treatments. Alterations that can be made to the historic structure by the architectural conservator to improve the environment in which the historic wallpaper hangs are also described. 1 INTRODUCTIONWALLPAPER, from the perspective of the architectural conservator, is an integral part of the interior decoration of a historic building. Used in combination with paint, molded woodwork and plaster moldings, wallpapers are hung to give a room's wall and ceiling surfaces color, texture and a decorative pattern. Most often historic wallpapers are applied directly to a room's plaster walls and ceilings. This direct application establishes the relationship of the wallpaper to the other architectural elements in the room—woodwork and plaster moldings. It also creates a physical bond between the wallpaper and the plaster wall surfaces, so that structural deterioration or environmental factors that result in damage to the substrate also cause damage to the historic wallpaper. Recognition of the interdependency of the wallpaper and the structure in which it hangs is crucial for successful wallpaper conservation. This interdependency requires that architectural conservators and wallpaper conservators collaborate so that conservation treatments to the wallpaper and the structure are compatible.1 Only if the wallpaper is a small fragment that will not remain in, or be returned to, its original location in the historic structure should it be treated as an isolated object. Architectural conservators in their work with historic buildings use early wallpapers in two principle ways—to restore an interior room to its appearance at a specific time in the history of the structure and to help document alterations that have been made to a room. This work involves two levels of wallpaper conservation—the conservation of entire rooms or large areas of historic wallpaper and the conservation of small wallpaper fragments. These levels of conservation have different treatment objectives, raise different practical and philosophical questions, and require varying degrees of interaction between the architectural conservator and the wallpaper conservator. 2 CONSERVATION OF LARGE AREAS OF HISTORIC WALLPAPERWhen entire rooms of historic wallpaper or large portions of a room's wallpaper remain, conservation, rather than reproduction of the historic wallpaper, is the preferred restoration objective. This preference for wallpaper conservation has only The conservation of entire rooms or large areas of wallpaper requires the collaboration of the architectural conservator, the wallpaper conservator, and the historic building curator. Figures 1–3 illustrate some of the problems encountered when conservation of an entire room of wallpaper is undertaken. Working together, they must determine the appropriate conservation treatment for a particular wallpaper based on the following criteria:

The artistic and historical significance of the early wallpapers found in historic buildings vary considerably. These variations should be reflected in the comprehensiveness of the conservation treatments which they receive. Two wallpapers located in National Park Service buildings illustrate this point well. The Zuber scenic “Paysage � Chasse” at Lindenwald, the Martin Van Buren National Historic Site in Kinderhook, NY, is both an artistically and a historically significant wallpaper. Its artistic significance is derived from the fact that it is a rag paper with a complex, block-printed scenic design. It is historically significant because it hung in the primary receiving hall at Lindenwald when it was the residence of the former U.S. President Martin Van Buren, the period to which the house is being restored. It is also one of a limited number of furnishings that can be positively dated to his residency at Lindenwald. This wallpaper is currently receiving extensive conservation treatments described in the presentation by James and Patricia Dacus Hamm. The other paper is located in the southwest parlor of the Narbonne House at the Salem Maritime National Historic Site in Salem, MA. This house is to be preserved as it was when it was acquired by the National Park Service in 1964; therefore, all the wallpapers in the house are to be preserved. This wallpaper is a mechanical wood-pulp paper, machine printed with a colonial revival design. It dates from c. 1930. This paper will receive only basic conservation treatments. It will be treated in situ—its surfaces dry cleaned and readhered to the plaster walls. Determination of the artistic and historic significance of a historic wallpaper is primarily the task of the building's curator.

Establishing the scope of the conservation treatment for a particular wallpaper falls mostly within the domain of the paper and paintings conservator; however, with regard to the decision of whether to treat a paper in situ or remove it from the walls for treatment, the architectural conservator has a definite bias. Since the architectural conservator considers wallpaper to be an integral part of the interior Determining the physical and environmental factors that most directly affect the stability of a historic wallpaper requires that the room in which the paper hangs be carefully monitored. This monitoring should include: structural movement in the plaster walls, the moisture content of the plaster walls, and the temperature, relative humidity, and levels of illumination, with the identification of the proportion of UV, in the room. Ideally, monitoring should be done for a full year so that the complete range of climate-related variations can be recorded. Evaluation of the monitoring data should be done by the architectural and wallpaper conservators. Based on the data, the architectural conservator should make any physical alterations required. For example, plaster walls can be stabilized by replacing rotten wooden sills or by plaster consolidation. The moisture content in an exterior wall can be reduced by repairing leaking roofs, gutters and downspouts and by repointing the exterior brick walls. UV filters can be put on the windows. Evaluating how a proposed wallpaper conservation treatment will affect the other architectural elements in a room is primarily the responsibility of the architectural conservator. The two principal criteria used by the architectural conservator to make this determination are:

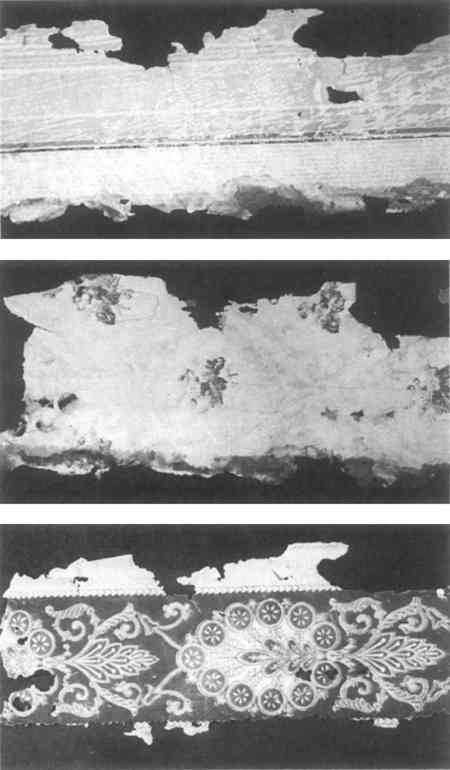

An example of an unacceptable treatment would be to rehang a conserved wallpaper by mounting it on a �″ thick frame, applied to the walls with a high strength bonding adhesive. The thickness of the frame would destroy the relationship of the wallpaper to the other architectural elements in the room—specifically any door and window frames, baseboards or cornice moldings. In addition, the bonding strength of the adhesive would remove a layer of the plaster substrate if the conserved wallpaper had to be removed at a later date. A final consideration must always be the monies available for conservation treatments. The funds available may determine the comprehensiveness of a treatment proposal. Insufficient funds may require that less complete treatments be carried out or that treatments be postponed. Postponement of conservation treatments raises the difficult question of what to do with a room of wallpaper in the interim. For example, how does an architectural conservator or a historic house curator prevent further damage to a torn wallpaper that is pulling away from the plaster walls? 3 CONSERVATION OF SMALL WALLPAPER FRAGMENTSSmall fragments of wallpaper are conserved primarily for documentary purposes—both in situ and in reference collections. The architectural conservator uses these samples to document alterations that have been made to interior rooms and as a basis for reproduction wallpapers. The size of small wallpaper samples enables the wallpaper conservator to treat the sample as a more isolated artifact. The level of collaboration required between the architectural conservator, historic building curator, and wallpaper conservator is greatly reduced. The small fragments of wallpaper found in a historic structure can provide an architectural conservator with a wealth of information, as illustrated by the three layers of wallpaper found when a door casing was removed from a first floor room at Lindenwald (see Figure 4). This information clarified what the original use of the room had been. Two uses had been claimed for the room—one a bedroom, the other a

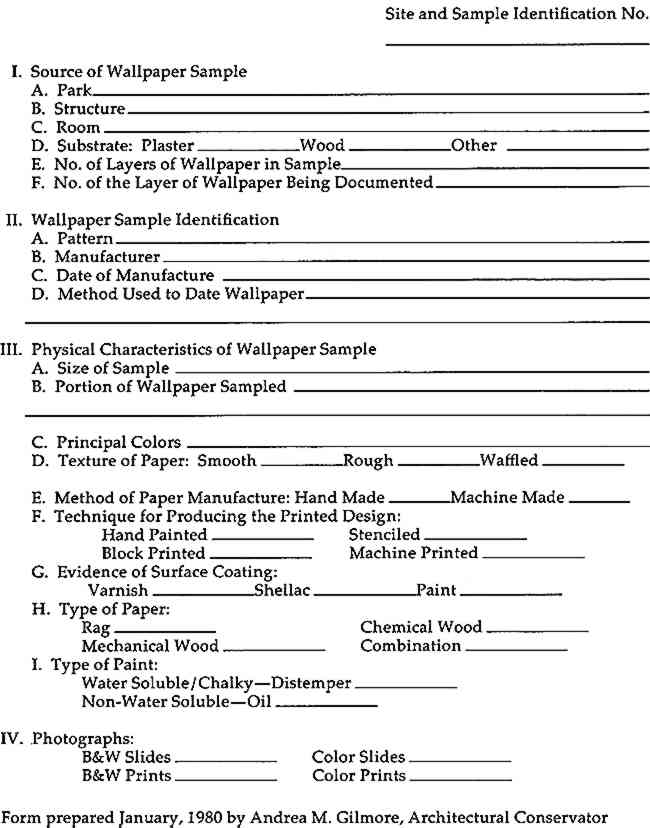

The three layers of wallpaper found under the door casing also confirmed that this exterior door was a later alteration. Since the room was built in 1850 and the kitchen moved into it some time during the late part of the nineteenth century, the addition of the exterior door probably coincided with this use change. The presence of the wallpapers under the door casing further indicated that the ceiling and plaster cornice of the room had not been painted originally. Comparison of paint samples from the plaster walls and the ceiling showed that they contained the same sequence of paint layers. The wallpapers found under the casing clearly indicated that the walls had been unpainted originally, indicating that the ceiling and plaster cornice had been unpainted originally as well. Since this room will be returned to its c. 1850 appearance, the room will be restored as a bedroom. This will entail removing the later exterior door and filling the opening. The three layers of wallpaper found under the casing will be removed and stored in the Park's historic wallpaper collection. The sample of the pink striped wallpaper, layer No. 1, will serve as the basis for a reproduction wallpaper to be used in the bedroom. Conservation of these samples involving cleaning, photographing, encapsulating in mylar and labeling. In the realm of wallpaper conservation, samples conserved for reference collections come the closest to isolated objects for purposes of treatment. Distinguishing characteristics of the wallpaper samples are also recorded on a standardized form (see Appendix A). At the Antram-Gray House at the Roger Williams National Memorial in Providence, Rhode Island, early nineteenth century wallpapers also proved valuable in documenting the evolution of the house. In a small room on the second floor, removal of a baseboard revealed a wallpaper with a border. The border of the wallpaper outlined an earlier set of stairs (see Figure 5). The Antram-Gray House, unlike Lindenwald, will not be restored to a specific period. Rather, the intent is to preserve, in situ, as much of the historic fabric as possible. The sample will require some cleaning, readhering and protection from abrasion after conservation. As with the conservation of entire rooms of wallpaper, measures should be taken to minimize the physical or environmental conditions that might cause damage to the wallpaper. In situ conservation of a small fragment of wallpaper, like the sample at the Antram-Gray House, requires limited interaction between the architectural conservator and wallpaper conservator.

4 CONCLUSIONWallpaper, from the perspective of the architectural conservator, is thus an integral element of the interior decoration of a historic structure. It presents the architectural conservator with the task of its documentation and conservation, and also may provide him or her with valuable information about the structural evolution of a building. The conservation of a historic wallpaper requires the collaboration of both architectural conservators and paper conservators, for the object being conserved and the structure in which it hangs are inextricably connected. Resolving the problems FOOTNOTESThe term “wallpaper conservator” is used in this paper to refer to the paper and paintings conservators who have combined their expertise to conserve historic wallpapers.

Perhaps the most concrete indication of this increased interest in historic wallpaper is the recent publication of Catherine Lynn's excellent book, Wallpaper in America. Ms. Lynn, in her introduction to her book, discusses this phenomenon. APPENDIX1 APPENDIX A1.1 NORTH ATLANTIC HISTORIC PRESERVATION CENTER WALLPAPER SAMPLE IDENTIFICATION FORM

Section Index Section Index |