THE CONSERVATION OF GEORGE WASHINGTON'S REVOLUTIONARY WAR CAMPAIGN MARQUEESFonda Ghiardi Thomsen, & Louise Cooley

ABSTRACT—The paper describes the treatment and preparation for exhibit of two large pieces of tenting used by General George Washington during the Revolutionary War Campaign. The techniques employed are fairly standard. The tremendous size and value of the objects involved required some practical and innovative application of these techniques. 1 INTRODUCTIONIn July 1974, the National Park Service, Division of Museum Services, received two pieces of tenting, believed to be part of George Washington's Revolutionary War Campaign Equipment. The tenting had been on exhibit since 1955 at the Colonial National Historic Park, Yorktown Visitors' Center. The tenting was examined and recorded for further research and identification. Conservation treatment was performed. The fabric was prepared for exhibit, then reinstalled in the new Yorktown Visitors' Center, July 1976. 2 HISTORYThe origin and history of ownership of the tents, which were known as marquees during the Revolutionary War Period, were researched.3 The reports concluded the objects in question were the inner sleeping chamber of the marquee used by General Washington as a private office and for sleeping, and the inner lining of the dining marquee for the Headquarters area. This was confirmed by the finding of an original order delivered to Plunket Fleeson, May 18, 1776, which called for “making a large Dining Marquee with Double Front,” and for “making another large Marquee with a Cham = (sic) out of ticken, Arch'd.” Possession of the marquees eventually fell to George Washington Park Custis of Arlington. They were pitched for the annual sheepshearing events at Arlington Springs, at Baltimore during Lafayette's visit of 1824, at Yorktown, and on numerous other occasions. During the Civil War, the Washington relics were confiscated and placed in the United States Patent Office. They were transferred to the United States National Museum in 1883. Mary Custis Lee appealed to President Johnson for the return of her personal goods. Finally, under President Taft, the Washington relics were returned to her. In August 1909, the Valley Forge Historic Society purchased the private office and sleeping marquee. In 1955, the National Park Service purchased the dining tent and equipment from the heirs of Mary Custis Lee. Currently, the Smithsonian Institution exhibits the dining marquee in their History and Technology Museum. The Colonial National Historic Park exhibits the inner sleeping chamber and dining tent roof lining discussed in this paper. The Valley Forge National Historic Park is preparing an exhibit of the private office and sleeping marquee. The marquee is on a ten-year loan from the Valley Forge Historical Society. The entire story of the marquees and what was received by the original purchasers is still not clearly established. 3 DESCRIPTION3.1 Inner Sleeping ChamberThe chamber was constructed of off-white, linen fabric, woven with “Z” twist, single-ply yarn, using a 2/2 broken, reverse, twill weave. The thread count was 19 threads/cm warp, 13 threads/cm weft. The total area of fabric was approximately 226 square feet. The mud flaps and ridge pole sleeve were constructed of plain woven, linen fabric, using the same yarn, with 12 threads/cm warp, 12 threads/cm weft. Grommet holes, where present, were hand bound with linen thread. Twelve fragments of hemp rope still hung from some of the grommets. Two well-oxidized remains of a small hook and eye were present on the top seam of the left side piece. Throughout the fabric were occasional patches of varying quality, made with an identical linen fabric. Other damaged areas were drawn together and sewn rather than patched. 3.2 Dining Marquee LiningThe main fabric was a plain woven wool, with a 22 thread/cm warp, and a 19 thread/cm weft. It was woven with very loosely hand spun, “Z” twist yarns of a non-uniform size. This caused the material to have a slightly seersucker appearance. The total area of fabric was 626 square feet. Examination of the fabric inside the French seams revealed a green color although the body of the fabric now appears mustard brown. The top side of the seams were reinforced with two-inch wide, heavy linen strips. Remnants of twelve wrought iron hooks remained on the linen strips. The ridge pole sleeve was a plain woven linen as on the sleeping chamber. 4 CONDITION4.1 Inner Sleeping ChamberThe main fabric was weak and riddled with holes, as shown in Figure 1. Fibers around the perimeter of the holes were colored dark brown. Microscopic examination of these brown fibers revealed a lighter tan color inside the fibers. These dark fibers were more brittle than the lighter fibers of the main fabric. Chemical tests conducted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation Crime Laboratory indicated the brown coloring was not due to an applied substance (such as tar, paint, etc.), fungus, or singeing. A test conducted at the laboratory with iron detection papers4 indicated a high concentration of iron. Some of the holes around the side sections appeared in a regular pattern. We know the chamber sides were attached to the top by a series of iron hooks and eyes. The fabric was rolled and stored for years. There was ample opportunity for ferrous degradation of the fabric to occur from the decomposing hooks and eyes.

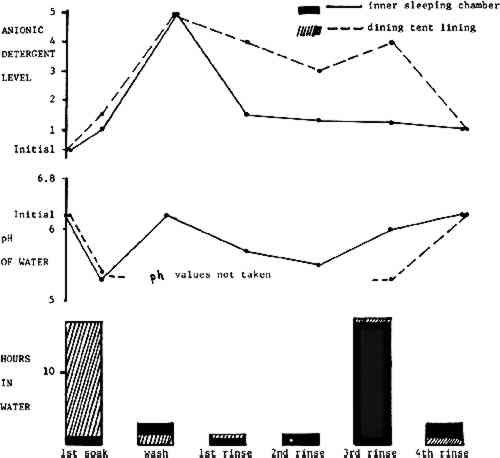

4.2 Dining Marquee LiningThere were numerous small rips and tears (less than one inch) throughout the woolen fabric. The fibers were brittle from age. Two large sections of fabric were completely missing. Discoloration of the fabric was most likely due to light damage. 5 TREATMENT5.1 WashingThe same procedure was used for washing both fabrics. Because of the immense size of the pieces, washing was done in a twelve by sixteen foot by six inch, polyethylene-lined plywood tank on the front lawn of the laboratory, as shown in Figure 2. The fabric was sewn between two, twelve by eighteen foot sheets of polypropylene screening5 for handling.

5.2 DryingTwo criteria governed the drying of these unwieldy pieces of fabric: (1) elimination of the weight of the water, and (2) drying of the fabric as rapidly as possible. There was no area within the building large enough to dry the fabrics completely opened out. Therefore, on a clear day, after the final rinse, each was laid out on six mil black polyethylene sheeting, on the sloping portion of the lawn to provide rapid drainage. This procedure gave the staff the opportunity to straighten warps, wefts, and seams, and remove as much additional water as possible with a neutral blotting paper, as shown in Figure 4. The fabric was refolded onto the washing screen, carried into the building and suspended on the screen from the ceiling of one of the laboratories, as shown in Figure 5. Dehumidifiers were used to reduce the relative humidity to fifty-five percent. Two large fans were run to circulate the air. The inner sleeping chamber was outside during drying about one and one-half hours. Complete drying inside was accomplished within six hours. The thinner dining tent lining was outside about forty-five minutes. Drying was completed inside within two hours. It is considered that the benefits derived from this outdoor drying far outweighed any theoretical damage which might have accrued by this somewhat unorthodox method of drying.

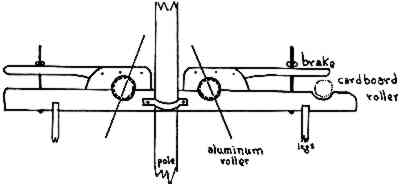

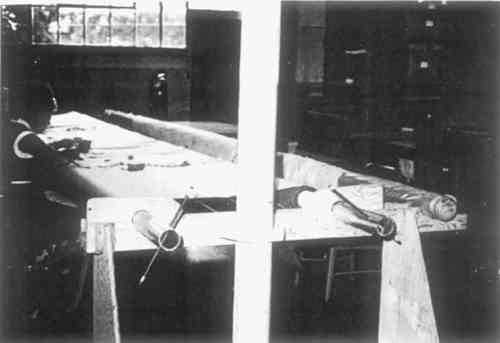

5.3 BackingThe fabrics were in a weakened condition. It was mandatory that they both be supported on the underside before rehanging on exhibit. 5.3.1 Inner Sleeping ChamberA one hundred percent linen fabric7 of approximately the same weight as the original, but with a plain weave, was purchased. Even though the original fabric was a twill, a twill backing would have permitted diagonal stressing to occur to the original fabric. A plain weave was selected to give uniform support in both the horizontal and vertical directions. One hundred percent cotton thread was used for the stitching. The backing fabric was washed and ironed at a commercial laundry, under the supervision of the conservators, to preshrink and remove size. 5.3.2 Dining Marquee LiningA two hundred count/square inch, one hundred percent cotton,8 plain woven sheeting, one hundred twenty inches wide, in the greige (unbleached), was obtained for the backing. Even though the original fabric was a lightweight wool, a stronger fabric was needed to support such a large area. The cotton provided the strength yet was lightweight enough to match the body of the original fabric. After washing to remove size, the cotton was dyed commercially9 to a mustard green color compatible with the present appearance of the original fabric. Three, thirty-foot lengths of linen were sewn together along their selvage edges to form the backing for the sleeping tent. Four, twenty-foot lengths of cotton were sewn widthwise for the dining tent backing. A framework, similar to tapestry repair frames used by the Mobilier Nationale at Gobelins in Paris, was constructed to permit the backing to be smoothly attached to each tent. The frame consisted of two, twenty-six foot long, parallel, friction-braked, aluminum rollers10 for holding the stretched backing, and a third roller of cardboard for supporting the historic fabric, as shown in Figure 6. With the backing tensioned between the two rollers, the historic fabric was unrolled a little at a time, laid across the stretched backing, and fixed into place by sewing, as shown in Figure 7. Four women were trained and supervised in this work by Mrs. Cooley. Heavy duty, one hundred percent cotton thread was used for stitching. All holes were sewn to the backing around their inner perimeters with a span stitch. The entire surface of the historic fabric was sewn into place

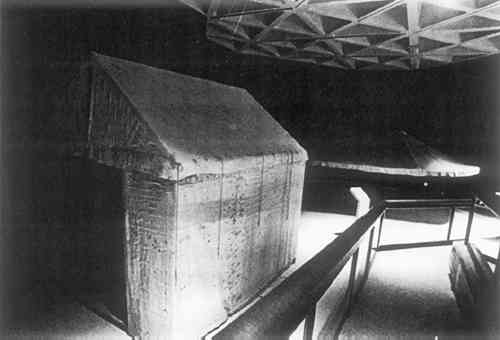

6 EXHIBIT PREPARATION6.1 Inner Sleeping ChamberUnfortunately, the conservators do not have final say in exhibit preparation. During the backing process, the sides were separated from the top, as was the original state of the marquee. A wooden frame, with two coats of shellac on the outside surfaces, was constructed to support the reinforced fabric from underneath. The backing fabric of the roof section was extended one inch beyond the edge of the historic fabric. This permitted the backing fabric to be stretched over the frame and fixed into place with nichrome staples without intruding on the historic fabric. A two-inch wide cotton tape was fitted with brass hooks every six inches and fixed to the frame around the edge of the roof. Cotton rope was stitched to the backing allowance left on the top of the side panels. The sides were hung on the frame in whatever position necessary. This arrangement simulated the historic hook and eye method which allowed the door to be placed wherever desired. 6.2 Dining Marquee LiningReproduction brass hooks were made and sewn to the linen tape where the originals were missing. The remaining iron hooks were degreased and waxed with 180� F microcrystalline wax. An oval frame was constructed from aluminum tubing, then covered with cloth tape. The oval frame was suspended from the ceiling. The historic lining was laid over this frame and held in place by stitching with linen thread over each hook, then around the frame. Tentative plans were made to put a mock outer marquee over this lining. The new visitor center was opened on March 28, 1976 (Figure 8).

7 CONCLUSIONSIt was felt the foregoing process was beneficial in stabilizing the two historic artifacts. The fabrics were much softer when treatment was completed. Decomposition products had been removed. The added backing supported the historic fabric and reduced the stress produced from hanging the fabrics on exhibit. The entire conservation process is reversible. REFERENCESConservator, National Park Service, Harpers Ferry Center, Division of Museum Services, Harpers Ferry, West Virginia 25425 Textile Conservator, 6506 Wilmett Road, Bethesda, Maryland 20034 Brown, William, Dr.LeeWallace, FrancesWard, National Park Service, Harpers Ferry Center, Division of Reference Services, Harpers Ferry, West Virginia 25425 Eisen-test papier, Fe++ and Fe+++, available from Gallard-Schlesinger Chemical Manufacturing Corporation, 584 Mineola Avenue, Carle Place, Long Island, New York 11514 No. 6951000, 15 mil polypropylene mesh 24 � 20 plain weave, Chicopee Manufacturing Co., Cornelia, Georgia 30531 OrvusW. A.paste (sodium lauryl sulphate), Procter & Gamble, Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 Linen No. 3151, 84″ wide, brown, Ulster Weaving Co., Ltd., 118 Madison Avenue (at 30th St.), New York, New York 10016 Type 200 100% cotton, 120″ wide, style #X7121, J. T. Stevens Company, 1185 Avenue of the Americas, New York, New York 10036 Kimtex Labs, 108 N. 7th Street, Patterson, New Jersey 07522 3–1/4″ outside diameter .25 inch thick aluminum pipe, A. B. Murray Corp., Bristol, Pennsylvania

Section Index Section Index |