CONSERVATION POLICY AND THE EXHIBITION OF MUSEUM COLLECTIONSNATHAN STOLOW

ABSTRACT—The author notes the increasing tendency for museums to place their collections on exhibition and travel, as part of an overall drive to decentralize and democratize collections. The conservation profession should recognize the shift of musuem priorities and devote more time to defining and researching problems associated with exhibitions and travel. A new category of Exhibition Conservator is proposed for dealing with the wide variety of conservation problems associated with buildings, their environment, exhibitions, and movement of works of art. The relationship between such a person and other specialists in the exhibition program is described.Among the problem areas cited are condition report standards, building surveys, and relative humidity levels for collections. Emphasis is placed on the need to maintain a suitable environment for objects at all times. 1 INTRODUCTIONThe traditional ordering of museum priorities are acquisition, conservation, and interpretation of collections. In more recent times the second and third priorities have been interchanged as more and more attention is paid in our society to the educational role of museums. There is increasing pressure to bypass (or minimize) conservation and preservation considerations in order to make collections more visible and accessible to the general public. Even storage is no longer sacrosanct. Few museums can retain the policy to keep 80% or more of their collections in storage. Such areas are rapidly becoming secondary exhibition areas. De-accessioning is now employed to remove deadwood from storage and to revitalize the collections. The museum can no longer be likened to an iceberg with only the tip showing. This is too expensive. As government and political authorities focus on the museum they see it increasingly as an educational instrument. It is not surprising to see the shift towards exhibitions and interpretation in the drive towards democratization and decentralization of collections.2 It is well for the conservation profession to accept this tendency and accordingly to adjust its own priorities. Efforts should be made to critically review existing methods and technology employed in the conservation of exhibitions and, where possible, develop newer approaches and standards. In the past decade, a significant proportion of the money and manpower resources available to the conservation profession has been devoted to essentially curatorial research; e.g. analytical studies and the characterization of materials of museum objects. This is, of course, very important, but thought should be given to reassigning our specialists to the present museum priorities. It should not be too difficult to redeploy some of the energy and manpower to focus on the various museological problems generated by a policy of democratization of collections. Thus newer and improved methods must be found to prepare objects for exhibition and travel. At the same time, it is necessary to restudy the question of environmental effects upon such objects and, on the basis of improved knowledge, arrive at more objective guidelines for the care of collections. In this context there must be closer study of such environmental factors as relative humidity, temperature (and their variations), airborne pollutants, light, and vibration. The reopening of this field of study will likely result in the development of the “exhibition conservator,” a professional conservator

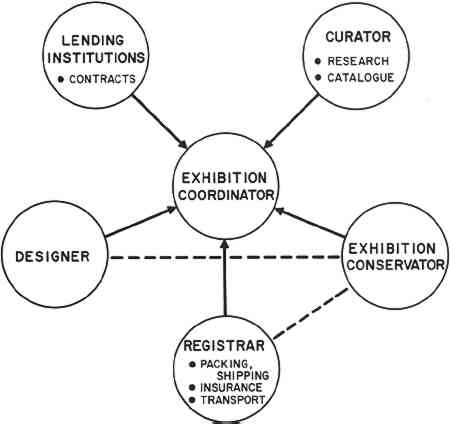

A certain amount of research has been carried out in the past on the environmental factors affecting collections. The “state of the art” of this field was described in 1967 at the IIC Congress on Climatology.3 Some significant work has been reported by various authors, more specifically on the subjects of environmental controls and conservation protection during exhibition and travel, and in the employment of the silica gel technique for microclimate control.4–15 There are many unanswered questions and voids in our knowledge of the effect of the environment upon collections. Likewise existing guidelines for control of environmental factors have to be reshaped in the light of new knowledge. For example, what is the rationale for a particular level of relative humidity for collections. What does ultimately happen to objects so exposed. Can panel paintings, under certain conditions, go out on loan? Does relining (or lining) a painting ensure greater safety from the vigors and hazards of travel? Further work has to be done to make more precise and meaningful condition reports. Efforts have been made to establish working vocabularies to describe condition.16,17 Nevertheless, it is not clear what are the actual relationships between environmental stresses and the resultant strains upon museum objects and works of art. There is the intriguing possibility even of delayed action, or fatigue. The whole area of preventative care remains vague. There are no reliable methods to anticipate the onset of a dangerous strain upon an object. What are the “fragility indicators” for paintings, drawings, sculptures, before the first appearance of their respective defects, e.g. cleavage, embrittlement, or corrosion. This paper is intended to stimulate greater interest and effort in the area of exhibition conservation—necessitating the reassignment of existing conservation priorities. 2 EXHIBITION PLANNING AND CONSERVATIONThe conception and planning of an exhibition originates at the top administrative level of the museum. This can have a major impact upon the conservator and his staff. It may be necessary for him to reschedule his work to meet the precise deadlines that exhibitions impose. As regards input at the planning stage the conservator can be called upon to ascertain that the items selected are in good condition. The condition criteria might vary from one conservator to another. There may be a feedback of this information to the exhibition organizers who have the option to choose objects of better physical condition or to arrange for conservation work to be done on the objects found to be fragile. More often it is the policy to keep to the original exhibition list and expect the necessary conservation measures to be taken in time for the opening. In relatively few museums does the conservator, or his equivalent, form part of the decision-making team on the selection of works for a particular exhibition program. Where this is done, the conservator may have useful input too on the physical and environmental

An excellent model of desirable conservation input into exhibition planning was in the organization of the International Exhibition at Expo 67 in Montreal,9 and more recently in the Chinese Archeological Exhibition.14 Naturally, in very large exhibitions the budgets and human resources are generous, allowing for elaborate precautionary procedures. In most museums the works on permanent display, and those in storage, are subject to more or less regular examination by the conservator. He evolves a priority list for treatment based on condition. Usually consultation takes place with the curators concerned. The workload may however be upset by more urgent requirements for assistance in a loan or circulating exhibition program. The deadlines imposed by these situations have to be met, and as a result, the basic conservation of the permanent collection suffers. In this context, too, it is difficult to carry out systematic research over a period of time. The conservator, therefore, spreads himself too thin to meet all the various demands for his services. A particular problem, and a challenging one, is that of the condition report. This report, which is normally written, with accompanying photographs or diagrams, is intended to describe, at a particular time, the actual physical state of the work or object in question. The difficulty is that no two conservators or curators agree precisely on the description of condition. The author recollects vividly remarks made by prominent specialists involved in the organization of certain major international exhibitions that particular objects were in “good” condition. The condition reports included such laconic descriptions. On closer examination by other equally prominent specialists, serious defects in condition were found that could give rise to cracking or losses. The situation is even more confusing in travelling or circulating exhibitions where the diagnosis of condition is successively delegated to the participating museums. It is extremely difficult, often impossible, to establish when a particular damage or condition arose as the individual entries in the report vary in detail and quality. Ideally for such exhibitions there should be one person responsible for assessing conditions at all points. This policy has been implemented in large, very important loan exhibitions where there are accompanying conservators or curators. However, even in this case there have been differences of opinion between the travelling conservator and the local museum conservator over assessment of condition or environmental control factors. A variety of forms have been developed over the years to record condition. Glossaries, or vocabularies have been devised to put more precision into condition reports.16,17 However, improvement can be made by publishing together with such glossaries, illustrative examples. Photographs are very useful to describe a particular condition difficult to record otherwise. There are pitfalls here too in that photographs may be slightly out of focus or taken in such a way as to minimize a particular defect. There clearly must be improvement in condition reporting so that there is common understanding of the terms used. It is not often that the conservator has any input into the handling and packing of exhibitions. In the past the conservator had little responsibility for this, as it is traditionally in the domain of the registrar, foreman of the shops, or the carpenter/shipper. If it is the policy to assign to the conservator total care, then it is difficult to see the logic in not involving the conservator also at the handling and packing phase of the exhibition. Regrettably, much of the packing in museums is still in a primitive stage. While the packaging industry has made much progress (through economic necessity), many museums, even the largest, are still in the “steam age.” The question of maintaining a suitable physical environment for exhibitions during the travel mode is a very difficult one to resolve. This matter has been researched upon, and in a few exhibitions humidity controlled cases have been successfully devised.10,14,15 It is as yet unclear what are the detailed effects of relative humidity and temperature variations, combined with vibration (or shock) upon the structure of museum objects. The basic principle remains to maintain the accustomed environment around the object at all times. It is difficult, however, to ascertain the “proper” environment that should be applied. Efforts have been made to develop loan procedures and criteria that safeguard collections from the conservation point of view.16,18 It would be worthwhile to canvass all major institutions to compare their procedures and criteria. These could very well be at variance with acceptable conservation policy. For example, on many restricted loan lists, panel paintings are not recommended for loan. Yet in such museums the existing environmental conditions are hazardous for hygroscopic objects, such as panel paintings. If consideration is given to the internal variations (microclimate) within “controlled humidity buildings” the hazards to collections can be appreciable. Hygroscopic objects remain dimensionally stable when their moisture contents remain constant. The protection of such objects lies in enclosing them in constant humidity environments until stability is achieved. Presumably a panel painting or hygroscopic sculpture can travel if it is stabilized within its constant humidity envelope. Traditionally, canvas paintings have been considered to be safe to lend, particularly after lining. There may be certain categories of such paintings that should not travel. It is difficult to estimate the effects of vibration and climate variation upon paintings with well-developed crack systems or of large format. A very concerted effort must be made to prepare conservation guidelines and criteria for exhibitions incorporating recent knowledge. Gaps in knowledge can be filled only by investigation and research. 3 ENVIRONMENT PLANNING AND CONSERVATIONEnvironmental factors have been referred to in the previous section, but will be elaborated upon in relationship to museum buildings, and their component parts. It is perhaps redundant to emphasize that the condition of an object is the result of the sum total of all its exposures to deterioration factors: during storage, conservation treatment, exhibition, and movement (travel). The housing of collections has therefore an important bearing on conservation. Museum architecture is a rather specialized field that does not have a long enough history or experience to offer guidelines and specifications for conservation. While progress has been made in developing newer approaches to exhibition halls, lighting and storage; humidity control, air movement, and filtration still pose great difficulties for the architect and the mechanical engineer. The conversion of older structures for museum use is a complex matter; likewise is the upgrading of the physical environment of museums built years ago. The concept of collaboration between architect and conservation specialist is rather recent. This new approach was incorporated in a number of the conclusions reached at the ICOM-UNESCO Symposium on Museum Architecture, Access, and Circulation, Mexico City 1968.19 Relevant conclusions are extracted:

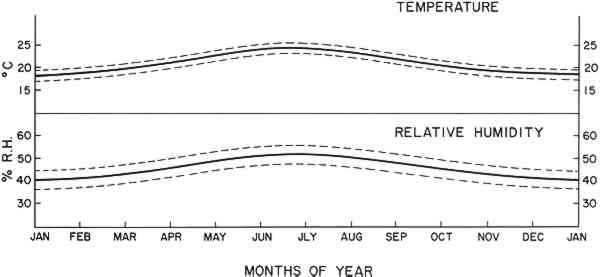

In some institutions surveys are conducted of museum buildings to establish their conservation-worthiness. Such surveys tend to be detailed, including records of humidity and temperature, and light intensity readings. The American Association of Museums embarked on a Museum Certification Program, a number of years ago, in which among a number of factors, environmental stability is assessed. In Canada, the National Gallery, many years ago, categorized art museums A, B, C, or D in descending order of professional and technical excellence. Building and environmental surveys are not only very important to the occupants and the collections housed, but also to other institutions who wish to lend or borrow objects. An inventory of building survey reports, including reliable historical data on relative humidity, temperature, air quality, and light levels would be very valuable to conservators and exhibition organizers. The weak point is the reliability of the instruments used in surveys, and the selection of locations for measurement of the various factors. The matter of level of relative humidity to be maintained for collections is still unsettled. It is generally agreed upon that constancy with narrow variation is essential for maintaining dimensional, or geometric stability for hygroscopic objects. It is also accepted that the temperature factor is less critical in these considerations. In 1960, ICOM carried out an international survey7 on desirable norms for relative humidity and temperatures. The answers were forthcoming from 3 archival institutions in Europe, and 29 major museums and galleries in Europe and America. The desirable levels varied considerably from highs of 60–70% to 45–50% for relative humidity, and from 15–22� C for temperatures. Obviously, there should be another survey, more detailed in nature, covering many more institutions and, this time, segregating the norms for classes of objects; e.g., paintings, works on paper, archival objects, sculptures (hygroscopic or otherwise), textiles, leather, ethnographic objects, ceramics and metals. Permissible variations should also be included, along with external climatic data for each reporting institution. In the author's experience with Canadian museums,20 there has been flexibility in the control levels over a twelve-month period to take into account the preservation of the building in a difficult climate. Thus in the winter time, the relative humidity can be set at 40 � 5%, and permitted to rise to 50 � 5% in the summer. The temperatures can likewise be programmed

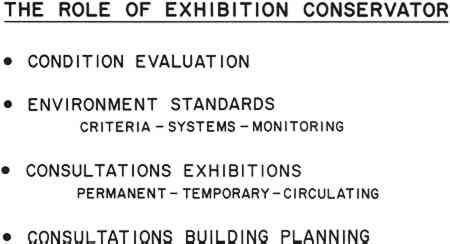

As regards lighting not much has been written on the conservation side since 1964.8 Generally, works on paper and textiles are being displayed at recommended low levels of ultraviolet-free light, 150 lux and lower, the fluorescent lamps and daylight sources protected with ultraviolet absorbing filters. There appears to be however a return of natural lighting to museums, partly as a reaction to the “dead” and unchanging aspect of artificial light. A compromise solution to this can be the location of windows or skylights remotely from the works of art, offering a psychological relief to the viewer. Architects find this solution attractive. The remaining factor of dust and dirt control can be resolved with filtration systems designed to eliminate dust and dirt particles down to certain levels (e.g. below 1 micron diameter). Atmospheric pollutants, e.g. sulfur dioxide, can be largely removed in filtration/wash system. However, in an industrial environment such pollutants can gain access through doors, windows, etc., and affect works of art. Thus careful attention must be given to the design of all building openings. 4 THE EXHIBITION CONSERVATORThe need for specialist conservators for the field of exhibition conservation is obvious. The responsibilities for such a person should include:

The person meeting these requirements should have practical conservation training at an acceptable institution and, additionally, some background in mechanical engineering, physics, meteorology, or similar disciplines. He should also have well-developed communication skills. Some conservators or museum scientists are already filling the role of exhibition conservator. It is far better, however, to develop this expertise in one person. The matter of the reporting relationship is somewhat difficult to resolve. The Exhibition Conservator should report to the Exhibitions Director, or failing that, to the Museum Director and should have a close functional relationship with the Conservation Department. 5 RECOMMENDATIONSThe following are recommendations for further development of the field of conservation of exhibitions:

6 CONCLUSIONSArguments have been put forward to develop a new awareness of the need to democratize museum collections on the part of the conservation specialist. The museum is moving rapidly forward as an educational institution, and the conservator must recognize the changing priorities. The policy of conservation in museums should be to assist in the realization of museum goals and determine newer and safe measures to give the public greater access to collections. The author himself is fully involved in this task and intends after a period of time to publish a definitive work on the subject of exhibition conservation. Any help from colleagues in the conservation and allied fields would be gratefully acknowledged. REFERENCESStolow, N., Ph.D., F.I.I.C., F.C.I.C.; Special Advisor (Conservation), National Museums of Canada, Esplanade Laurier, 22 NW, Ottawa, Canada K1A 0M8. Pelletier, G. “Museums and Government. Democratization and Decentralization. A New Policy for Museums.” ICOM News 25 (1972): 219–222. Thomson, G., ed. “Contributions to the London Conference on Museum Climatology 18–23 Sept. 1967.” p. 237. London: International Institute for Conservation of Artistic and Historic Works, 1968 (Revised). Toiski, K. “Humidity Control in a Closed Package.” Studies in Conservation4 (1959): 81–87. Thomson, G. “Relative Humidity—Variation with Temperature in a Case Containing Wood.” Studies in Conservation4 (1964): 153–69. Buck, R. D.Private Communication Regarding the Transit of Masterpieces of Flemish Art: Van Eyck to Bosch, Detroit and Bruges, 1960—in which a constant R.H. of 50% was maintained. Plenderleith, H. J., and PhilippotP. “Climatology and Conservation in Museums.” Museum13 (1960): 202–289. Feller, R. L. “Control of Deterioration Effects of Light Upon Museum Objects.” Museum17 (1964): 57–98. Stolow, N. “The Technical Organization of an International Art Exhibition.” Museum21 (1968): 182–240. Stolow, N. “Fundamental Case Design for Humidity Sensitive Museum Collections.” Museum News February 1966: 45–52. Stolow, N.Controlled Environment for Works of Art in Transit. p. 46. London: Butterworths, 1966. Beale, A. “Materials and Methods for the Packing and Handling of Ancient Metal Objects.” Paper Read at 10th Annual Meeting of International Institute for Conservation of Artistic and Historic Works—American Group, May 31–June 2, 1969, at Los Angeles, California. Lefeve, R., and Goorieckx, T. “Le transport de las chasse de St. Remacle de Stavelot a l'exposition de Montreal.” Bulletin, I.R.P.A.10 (1967–68): 183–88. Leech, B.Private communication regarding use of preconditioned silica gel for Chinese Archeological Exhibition in Toronto, Canada, Oct.–Nov. 1974. Also on the subject of the technical organization of this exhibition. Toiski, K.; Nishikawa, K.; and Washizuka, H.Unpublished paper prepared July 1975 for Meeting of Experts on Care of Works of Art in Loan Exhibitions between United States and Japan. Dudley, D. H., and Wilkinson, I. B., et al. “Museum Registration Methods.” Revised. Washington, D.C.: AAM and Smithsonian Institution, 1968. Buck, R. D.Museum Registration Methods, loc. cit. 16. The Inspection of Art Objects and Glossary for Describing Condition, pp. 164–70. Fogg Art Museum. “Loan Procedure and Criteria.” Duplicated. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University, 1974. Symposium on Museum Architecture, Access, and Circulation. Organized by ICOM-UNESCO, Mexico, December 8–14, 1968. Reported in ICOM News March 1969: 39–42. Private communications and consultations—Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto); International Fine Arts Gallery—Expo 67 (Montreal); Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Montreal); National Museums of Canada (Ottawa); in the period 1966–76. Private communications and consultations with Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Ill. 1973–74.

Section Index Section Index |