INTEGRATING PREVENTIVE CONSERVATION INTO A COLLECTIONS MOVE AND REHOUSING PROJECT AT THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIANEMILY KAPLAN, LESLIE WILLIAMSON, RACHAEL PERKINS ARENSTEIN, ANGELA YVARRA MCGREW, & MARK FEITL

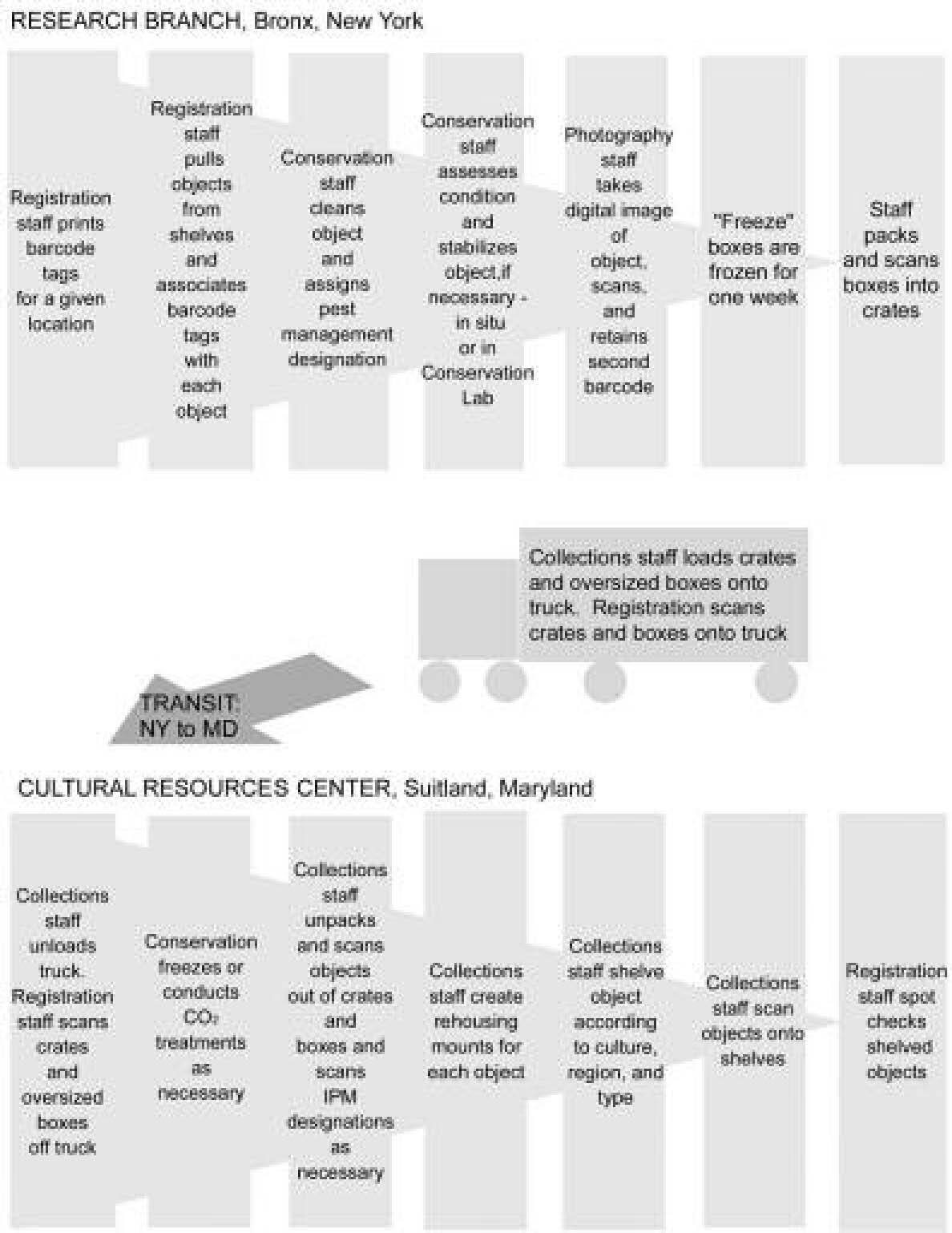

ABSTRACT—In June 2004, the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of the American Indian finished transporting its collection, comprised of approximately 800, 000 archaeological and ethnographic artifacts from native cultures throughout the Western Hemisphere, from the museum's Research Branch in the Bronx, New York to the new Cultural Resources Center in Suitland, Maryland. The project took five years to complete and finished on budget and ahead of schedule. Conservators at the New York and Washington, D. C. venues worked to institute high standards of collections care that were integrated into the move and rehousing process. Collaboration with Collections Management, Registration, and Photography staff resulted in the establishment of preventive care procedures for object handling, pest management, packing, transport, and rehousing. This reduced direct object handling. Interventive conservation treatments were minimal and temporary stabilization measures were used often. This paper describes the preventive conservation procedures developed over the course of the project and assesses the immediate and long-term benefits of these processes. L'int�gration de la conservation pr�ventive au sein du projet de d�m�nagement et de relocalisation des collections du National Museum of the American Indian. R�SUM�—En juin 2004, le National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) (mus�e national des cultures am�rindiennes), un mus�e faisant partie du Smithsonian Institution, compl�tait le d�m�nagement de sa collection d'environ 800, 000 objets arch�ologiques et ethnographiques provenant de cultures autochtones diverses de l'h�misph�re occidental, d'� partir du Bronx, un quartier de New York, jusqu'aux nouvelles r�serves du Cultural Resources Center (centre des ressources culturelles) � Suitland, au Maryland. Ce vaste projet d'une dur�e de cinq ans fut compl�t� avant �ch�ance et sans d�passer le budget allou�. Les restaurateurs de sites � New York et � Washington D. C. ont �labor� un plan d'action en conservation pr�ventive, afin que des mesures pr�ventives suivant les plus hautes normes soient int�gr�es dans toutes les �tapes du projet de d�m�nagement et de relocalisation. Une collaboration �troite fut tiss�e avec le personnel de la gestion des collections, le bureau du registraire, ainsi que le personnel en charge de la documentation photographique, ce qui eut comme r�sultat l'�tablissement g�n�ralis� de proc�dures en mati�re de conservation pr�ventive, plus pr�cis�ment concernant la manutention des objets, le contr�le des insectes, ainsi que l'emballage, le transport et la relocalisation des objets. Ces proc�dures visaient entre autres � r�duire les manutentions directes des objets. Les interventions de traitements furent r�duites au minimum, alors que des stabilisations temporaires furent plut�t fr�quentes. Cet article d�crit les proc�dures de conservation pr�ventive qui furent d�velopp�es durant ce projet et en dresse un bilan positif, � court et � long terme. Integraci�n de la conservaci�n preventiva en un proyecto de mudanza y reubicaci�n de colecciones del National Museum of the American Indian (Museo Nacional del Ind�gena Americano). RESUMEN—En junio de 2004 el Museo Nacional del Ind�gena Americano del Smithsonian Institution (Instituci�n Smithsonian) finaliz� el transporte de su colecci�n, que comprende aproximadamente 800, 000 artefactos arqueol�gicos y etnogr�ficos de las culturas nativas del Hemisferio Occidental, desde la Divisi�n de Investigaci�n del museo en el Bronx, Nueva York, al Nuevo Centro de Recursos Culturales en Suitland, Maryland. Llev� cinco a�os completar y terminar el proyecto, dentro del presupuesto y antes de lo programado. Los Conservadores de las instituciones de Nueva York y Washington, D. C., trabajaron para establecer altos est�ndares en el cuidado de las colecciones que fueron integradas al proceso de mudanza y reubicaci�n. La colaboraci�n con el personal de Administraci�n, Registro y Fotograf�a de las Colecciones tuvo como resultado la creaci�n de procedimientos de cuidado preventivo en la manipulaci�n de objetos, el manejo de las plagas, el embalaje, el transporte y la reubicaci�n. Esto redujo la manipulaci�n directa de los objetos. Los tratamientos interventivos de conservaci�n fueron m�nimos y se emplearon con frecuencia medidas temporales de estabilizaci�n. Este articulo describe los procedimientos de conservaci�n preventiva desarrollados durante el curso del proyecto y eval�a los beneficios inmediatos y a largo plazo de estos procesos. T�TULO—Integrando a conserva��o preventiva ao projeto de mudan�a e re-acondicionamento das cole��es do National Museum of the American Indian (Museu Nacional do �ndio Americano). RESUMO—Em junho de 2004 o Smithsonian Institution National Museum of the American Indian (Museu Nacional do �ndio Americano, do Instituto Smithsoniano), terminou a mudan�a da cole��o de aproximadamente 800 mil artefatos arqueol�gicos e etnogr�ficos de culturas nativas do hemisf�rio ocidental, de seu Research Branch (filial dedicada � pesquisa) localizada no Bronx, Nova Iorque, para o novo Cultural Resources Center (Centro de Bens Culturais) localizado em Suitland, Maryland. O projeto, realizado em 5 anos, manteve-se dentro do or�amento e foi conclu�do antes do prazo previsto. Conservadores de Nova Iorque e Washington D. C. trabalharam na cria��o de padr�es de alto n�vel para a conserva��o das cole��es, integrados aos processos de mudan�a e re-acondicionamento. A colabora��o entre as equipes de Gerenciamento de Cole��es, Registro e Fotografia possibilitou o estabelecimento de procedimentos preventivos voltados ao manuseio de objetos, controle integrado de pragas, embalagem, transporte e re-acondicionamento. Estes procedimentos reduziram o manuseio direto dos objetos. Os tratamentos interventivos de conserva��o foram reduzidos ao m�nimo e as medidas tempor�rias de estabiliza��o foram adotadas com freq��ncia. Este artigo descreve os procedimentos de conserva��o preventiva desenvolvidos no decorrer do projeto e avalia seus benef�cios, tanto imediatos quanto a longo prazo. 1 INTRODUCTIONAt the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) a strong program of preventive conservation was the foundation of a successful collections move project in which objects were moved safely and efficiently. This success was a direct result of collaboration and communication between several departments: Conservation, Collections Management, Registration, and Photography. It need not be, nor should it be, the responsibility of the Conservation Department alone to ensure the preservation of the collection through preventive conservation. The roles and responsibilities of each department are outlined, with the role of the Conservation Department in guiding the preventive conservation program discussed at greater length. The preventive conservation program was so integral to the project that the responsibilities for implementation became less distinctly divided by department and were generally accepted and undertaken by all staff involved in the Move Project. 2 BACKGROUND OF THE MOVE PROJECTDuring the course of the five-year Move Project NMAI transported more than 800, 000 Native American archaeological (607, 089) and ethnographic (168, 622) objects from the NMAI Research Branch, a crowded warehouse in the Bronx, New York, to the museum's Cultural Resources Center, a purpose-built research and storage facility in Suitland, Maryland. For the duration of the project, a truckload of objects was shipped between the two facilities almost every week. One hundred and seventy-seven people participated in the project: 140 staff members and contractors, 25 volunteers, and 12 interns. In order to speed progress, a fine art moving company was hired to pack, rehouse, and shelve the archaeological collection under the supervision of NMAI staff. NMAI staff were responsible for moving and rehousing the ethnographic collection. The project finished in June 2004. Registration, Conservation, Photography, and Collections Departments staff coordinated efforts to prepare objects to travel from the Research Branch, and to receive and rehouse them in Maryland. While the Move was considered a successful project because it was completed safely, on time, and under budget, other long-term benefits were realized at the same time. Every object was cleaned and, if necessary, stabilized. High-resolution digital photographs taken of each object, in addition to assisting in the move, have helped increase access to the collection, and it is hoped, will minimize the need for handling in the future. The Move Project also served as an impetus to upgrade the museum's system for tracking individual objects and facilitated reconciliation of registration and inventory problems. The Move Project represented a turning point in the history of the NMAI collection. George Gustav Heye, founder of the Museum of the American Indian, built the Research Branch specifically to house his Native American collections. For 80 years, the Research Branch served a community of scholars who sorted through textiles, ceramics, beadwork, and the many other objects in Heye's richly varied collection. 2.1 PREPARATION FOR THE MOVEThe implementation of good preventive care methods began in the planning stages of the move. Move preparations consisted of three main elements: a complete registration inventory, a collection-wide condition survey, and a Pilot Move Project. The registration inventory and condition survey were carried out concurrently. Five conservation technicians and twelve registration technicians were hired on a temporary basis for the one-and-a-half-year project. 2.1.1 Registration InventoryThe goal of the inventory was to reconcile discrepancies in the museum's database and record existing storage locations at the Research Branch for each object. The registration inventory and collection-wide condition survey were conducted with one conservator working with two Registration staff. This teamwork ensured that objects were handled only once while both registration and conservation data were gathered. The conservator was able to provide advice on handling problematic artifacts as well as education on materials and deterioration. This type of collaboration became a hallmark of the later Move Project. 2.1.2 Condition SurveyThe condition survey provided an opportunity to anticipate the needs of the collection with the presumption that the Move Project would proceed more efficiently if objects were stabilized ahead of time. The goal of the survey was to identify all objects with condition problems severe enough to require treatment in order to safely transport to Suitland. Objects were ranked on a scale of 1–3. A designation of #1 was given to objects requiring some form of treatment in order to be moved safely. Comments about condition and anticipated needs were entered into a database and the objects reshelved for later attention. Objects with a #2 designation were those that did not require treatment before transport but could benefit from monitoring and/or treatment, which could be done at some point in the future once the objects arrived in Maryland. A #3 designation was given to objects that were stable. Many of the objects assigned a #1 designation were given temporary or minor “triage” stabilization treatments conducted in situ in the storage areas during the survey. Temporary treatments included bagging objects with loose elements or using Teflon tape to secure unstable pieces. Minor treatments included using adhesive to secure loose beadwork or consolidating areas of spalling slip on ceramics. 2.1.3 Pilot MoveA Pilot Move project was undertaken before the official start of the Collection Move. The Pilot Move was designed as a way to work out strategies for data tracking, conservation, packing methods and materials, digital imaging, and staffing in order to make an informed plan for the move of the entire collection, and as a way to make necessary space available for the first of several staging areas for the move of the rest of the collection. Later, it was used as a test for the data tracking system when the objects were unpacked at the Cultural Resources Center. During the Pilot Move, 16, 450 archaeological objects from a discrete portion of the Ecuadorian and Caribbean collections were moved by museum staff to off-site storage; the Cultural Resources Center was still under construction. This segment of the collection was selected because the material was mostly inorganic, relatively robust lithics and ceramics. Sizes ranged from small finds and sherds to 200–300 pound stone thrones from Ecuador. It was anticipated that with this group of objects, packing methods could be easily standardized, the objects would be relatively straightforward to image, and environmental and pest management concerns would be minimized. The Pilot Move was broken down into four essential activities that were executed by members of different departments acting together as a team. First, Several important lessons learned from the Pilot Move influenced the development and procedures of the main Move Project. For example, people from each department worked together as a team during the course of the Pilot Move. Although this seemed like a good idea, it resulted in bottlenecks in the workflow. For example, some objects could be cleaned and imaged quickly but required a great deal of time to pack, and vice versa. The Move Project ultimately was organized more like an assembly line, which improved efficiency and at the same time required more flexibility. For example, in the Pilot Move objects were removed from storage and cleaned first by Conservation staff. This worked well as conservators could address an object's stability problems before it received much handling. During the main Move Project, the Registration team was responsible for removing objects from storage. The change in the work order required that Registration staff receive thorough handling training and assistance from the conservators. Another lesson learned was that the systems that were safest and most efficient for transit were often not practical for storage. The decision for the Move Project to separate packing and rehousing processes allowed the museum to use non-archival packing materials that could save money and be easily recycled during the project. An exception to this was oversize objects for which it was often best to construct a mount that served for both travel and storage. The Pilot Move helped in the initial development of move procedures but could have been even more useful had it included a more representative group of objects such as a variety of organic objects. 3 OVERVIEW OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN MOVE PROCESSES3.1 PROCEDUREThe NMAI Move worked on an assembly line system that created a linear flow of objects through the several departments, culminating in the successful rehousing at the new facility (fig. 1). The handson work flow proceeded in this order: at the Research Branch, Registration staff pulled objects from old storage locations, generated and associated a unique printed barcode tag with each object, and sorted them according to cultural group (ethnology collections) or provenance (archaeology collections). Conservation staff then inspected and vacuum cleaned the objects, stabilized them as necessary, and assigned a pest management treatment. Next, Photography staff took a high quality digital photograph of each object. Collections Management staff packed each object into boxes and then the objects, in boxes, underwent pest management treatment as required. The boxes were then crated and transported by truck to the Cultural Resources Center. There, Collections staff unpacked and sorted the objects, Conservation staff inspected objects and oversaw any additional pest management not carried out at the Research Branch, and Collections staff rehoused and shelved each object. Throughout the process Registration staff managed data from barcode scanning. All of these tasks were necessary and integral to the safety of the objects, and some of the tasks provided crucial information for the museum as well. However, the sheer number of steps and functions involved in the workflow resulted in an enormous amount of handling. In order to make this system safe and efficient, preventive conservation procedures were instituted and staff were crosstrained and flexible so that they could shift between tasks to alleviate bottlenecks formed when more difficult objects were being moved. Flexibility was especially valuable when working with the ethnographic collection, which was relatively varied in material composition and condition compared to the archeological collection. 3.2 STAFFINGStaff within the Move departments, Conservation, Registration, Collections Management, Photography, and Administration,

Administration/Management

Conservation

Registration

Collections Management

Photography

4 THE ROLE OF CONSERVATION IN THE MOVE PROJECTConservators worked during the planning stages of the project to establish preventive care policies and procedures. The goal was to integrate precautions into standard practices so that damage prevention was simply part of doing the job right. From the outset, conservators defined appropriate methods, materials, and techniques. This made it possible for the team to refine and streamline day-to-day work while following sound conservation guidelines. For the duration of the project, Conservation staff at both the Research Branch and the Cultural Resources Center served as a resource for:

4.1 CONSERVATION ACTIVITIES AT THE RESEARCH BRANCHThe daily hands-on work of the Conservation staff at the Research Branch began with evaluating the stability of each object based on the potential for loss and damage during the move. Conservation staff then cleaned each object with a Nilfisk vacuum with variable suction and a HEPA filter to remove evidence of past insect activity, and to remove surface dust and dirt accumulated during storage which might otherwise be ground into the object's surface. Vacuum cleaning also served to remove or reduce potentially hazardous surface contaminants such as lead, arsenic, mercury, and plaster dust from previous treatments or storage. Following cleaning, Conservation staff:

4.2 CONSERVATION ACTIVITIES AT THE CULTURAL RESOURCES CENTER

Hands-on work for the Move Conservation staff at the Cultural Resources Center was less specific than that of the staff at the Research Branch. Each object did not go through the hands of a conservator. Instead conservators evaluated the condition of objects when they arrived at the Cultural Resources Center and throughout the rehousing and shelving process by maintaining a constant presence and working closely with staff. Interventive treatment was minimal, consisting only of repairing some small damages when the object would be more safely housed if repaired, and minor stabilization treatments such as stabilizing a strand of loose beadwork. Objects with limited damage or other problems were documented and will remain in storage until they might become a priority for exhibit. Conservators supervised:

4.3 PLANNING AS PREVENTIONOne of the primary roles of Conservation was to prevent move-related damage to the objects by establishing sound preventive care procedures. This included establishing appropriate handling, packing, and rehousing procedures and materials even before the first object was moved. Given the nature of the collection, Conservation staff realized that handling during the move process would be the greatest potential cause of damage. In order for each department to do its work, the objects would need to be handled multiple times. From the beginning it was considered essential to put procedures in place to minimize handling and make necessary handling as safe as possible. While the preventive methods used varied at the Research Branch and the Cultural Resources Center, the commitment to putting object care first was always primary. It was a tremendous asset to have staff with varied backgrounds and prior experiences. Carpenters, sculptors, artists, archaeologists, teachers, and textile artists as well as collections managers and conservators worked together to improve the efficiency, safety and quality of the systems and to continually integrate new ideas into the process. 4.3.1 Staff Training and Communication4.3.1.1 TrainingConservators conducted mandatory, formal object handling training and periodic refresher sessions for all members of the Move team including contractors, volunteers, and interns. At the Cultural Resources Center this also included all museum staff who would be handling collections, whether for the Move or for other projects. The training sessions emphasized preventive measures, particularly safe movement of objects within the building using carts, lifting devices, and transit supports, along with how to physically handle objects. Training included an overview of the entire move process so that new staff could gain an understanding of the inevitable handling each object would receive. The Conservation Department also worked to educate staff on object material identification and common deterioration problems, and to be aware of the potential for specific problems or conditions that could not be corrected with treatment during the Move. Examples include “glass disease” frequently found on glass trade beads, shredding common to cedar bark, weak old vegetable-tanned leathers, fragile weighted silks, waxy deposits on some plant materials, and some types of copper corrosion. 4.3.1.2 CommunicationGood communication and asking questions were emphasized as important elements in preventing damage. Team members were instructed to alert a conservator immediately with any handling problems, questions about artifact materials or construction, pest management concerns, and damage or potential for damage. Communication between managers at the two facilities was also aided by the use of e-mail messages, often with explanatory digital photographs attached. To assist communication between departments and facilities, conservators and packers at the Research Branch attached notes to crates, boxes, and objects to alert Conservation at the Cultural Resources Center to particular condition concerns, special packing, and new packing systems needing evaluation and documentation on unpacking. Some notes addressed common or recurring

4.3.1.3 Minimizing Handling During Move ProceduresAt the Research Branch, object handling was minimized mainly by using support boards and trays designed and constructed to fit in modular fashion onto multi-tier rolling carts. Some of these systems have been described in detail elsewhere (Arenstein et al. 2003). By placing each object on a board many of the required steps could be accomplished with little or no direct manipulation of the object. The use of trays also facilitated keeping multiple objects together, and assisted in keeping loose barcodes associated with the correct object until they were packed. Die-cut polyethylene foam rings were useful as temporary supports for round bottom ceramics, and Tyvek and polyethylene foam sheet cut to standard sizes were useful lifting sheets for other objects. 4.3.1.4 Minimizing Handling During Rehousing and StorageAt the Cultural Resources Center, the storage areas were designed to be as accessible as possible within the limitations of a compactor storage unit system. An archival storage mount was constructed for each object. The intent was to make the supports safe, functional, unobtrusive, and aesthetically pleasing so that objects would not undergo unnecessary physical handling, and would be visible while still in the mount. Cultural Resources Center staff were trained to inspect each object for any damage, weakness, or inherent instability before designing and constructing the storage mount. This brief examination assisted the staff in choosing the most appropriate materials and method of support construction. Storage supports are described in detail elsewhere (NMAI 2004). Materials used included standard museum supplies such as acid-free corrugated board, Coroplast, Tyvek, closed-cell polyethylene foam plank and cross-linked polyethylene foam sheet (NMAI 2004). Most threedimensional objects were stored in trays, which facilitated handling and contained any detached fragments. Wherever possible, staff used custom die-cut Coroplast and archival paperboard trays, designed in standard sizes to fit the Cultural Resources Center shelving configurations. Many of the artifacts, however, required custom trays. These trays too were The compactor storage units are thirteen feet high, requiring the use of mechanical lifts and ladders to shelve and retrieve objects. Most artifacts were stored in drawers in which any loose objects might shift. Three-dimensional objects therefore required foam blocking to keep them from shifting in storage. Tri-rod, a triangular extruded polyethylene foam backer rod, and Minicel, a cross-linked polyethylene foam plank, both have smooth cut surfaces and so proved especially time-efficient for blocking objects into storage supports. Several types of objects did not lend themselves to placement in storage trays at the Cultural Resources Center but were still housed in standardized systems. For example, ceramics that did not have any loose elements or friable surfaces were placed on Coroplast pallets (rather than in a tray) and supported with foam wedges hot glued to the pallet. The majority of the textiles, basketry mats, and hides were rolled onto acid-free tubes and covered with Mylar, muslin, or Tyvek 1443R. Garments and textiles that could not be rolled for long-term storage were laid flat on a piece of Tyvek 1025D cut to fit the dimensions of the object, and stored flat or with as few folds as possible on a screen. Folds were padded out with backer rod. Custom mounts were constructed for oversized objects such as watercraft and totem poles. Unlike the procedures used for most of the collection, the travel mounts for oversize artifacts were usually designed to serve as a storage mounts as well. 4.3.2 Limiting Transit VariablesA primary concern when a fragile object travels is protecting the object against a worst-case travel scenario. Every decision from the extent of stabilization to the design of packing and crating systems, is made with this concern in mind. The object must be able to withstand handling by untrained personnel, and the packing systems must be able to function well despite any number of variables, including the unforeseen. The key to the NMAI Move was strictly controlling the travel environment so that these variables were limited. NMAI staff carried out the work on both the shipping and receiving ends, which meant that there was little need to vary procedures. As transit procedures and packing methods were designed specifically for the logistics of this particular move (NMAI 2004) systems could be mass-produced and standardized to maximize efficiency, control costs, and ensure safety for both objects and staff. 4.3.2.1 TransportA truck trailer was leased for the duration of the project, and thus was under NMAI control at all times. This allowed staff to develop standardized packing and crating for the majority of the collection, assuring that proper packing, loading, and handling of the collection was achieved with the smallest possibility for error. 4.3.2.2 Controlling the Transit EnvironmentSince the crates were in a predictable and controlled setting at all times, climate control for the collection was predictable and easy to maintain. From the beginning, it was determined that when the objects were packed in boxes, sealed in plastic, then padded and loaded into the standard reusable polypropylene crates, they experienced only very slow and very gradual changes in temperature and relative humidity. The leased trailer had a new, wellmaintained reefer (temperature control) unit and airride suspension, and a controlled environment was maintained in the loading docks of both facilities. Hobo dataloggers were used on each truck shipment to verify the conditions to which the collection was subject and to constantly assess and refine packing to meet climate requirements. Shock bug dataloggers were used periodically to check the amount of shock a packed crate unit encountered during transit. The level of shock registered by normal packing systems was consistently low. This was due partially to the use of air-ride trailers, but mainly to good initial planning for the overall system. 4.3.3 Standardizing Packing and Crating Systems

4.3.3.1 Crating and Cushioning SystemSince project staff had complete control over the various stages of transport and housing, the most logical approach for packing design was from the trailer load down to the object. The most efficient use of space in the trailer was a reusable modular system that fit within the dimensions of the trailer, thus reducing movement during shipping and facilitating easy loading and unloading. NMAI chose a reusable, stackable pallet crate system made by Kiva International. These standard-sized crates are made from molded polyethylene/polypropylene bases with lids made to latch to a 10mm corrugated folding sleeve. They are designed to lock together when stacked and can be easily moved in stacks with pallet jacks. The padding system within the crates was designed to cushion to three specific load ranges that accommodated almost all of the collection: zero to 180 pounds, 180 to 400 pounds, and 400 to 1000 pounds. Research Branch Move staff constructed these cushioning panels by sandwiching polyurethane ester foam between two layers of corrugated polypropylene board. This gave a lightweight yet durable reusable cushioning platform on which to stack the packed boxes. Inner boxes were ordered in nine custom sizes that could be stacked in different configurations to form a cube precisely fitting the interior of the Kiva unit. In order to withstand multiple re-use these boxes were made from durable 275 lb. double wall corrugated cardboard. The packing systems were designed to address shock, vibration, the potential for changes in temperature and relative humidity, as well as the risk of any off-gassing from packing materials. Typically the objects remained packed for approximately three weeks during pest management, shipping, and sorting. The short turn-around time from packing to unpacking allowed for the use of standard, non-acidfree cardboard boxes, eliminating the need for a large investment in acid-free boxes. 4.3.3.2 Packing MethodsWhen staffing the project it was considered essential that the Assistant Move Coordinator for Collections at the Research Branch, who would be in charge of packing, be someone well versed in and committed to preventive conservation procedures. By sharing the responsibility for preventing harm to the objects, the Assistant Move Coordinator collaborated with Conservation staff to streamline and improve upon the procedures used throughout the life of the project. Since the crating and trucking system minimized risks associated with the environment around the objects, the packers were freed to concentrate on the primary concerns of the artifacts themselves. A variety of standardized packing methods designed to isolate and/or stabilize the individual object within the inner box were developed to meet the needs of the majority of the collection. These systems are described in detail elsewhere (NMAI 2004). All of these systems relied on the reusable bottom and side cushioning panels placed between the packed boxes and the Kiva units, alleviating the need to provide individualized padding for each object. 4.3.3.3 Materials RecyclingThroughout the course of the project, packing and crating materials were recycled between the two facilities. Each truck loaded with artifacts for transport to Suitland was returned to the Bronx carrying reusable packing materials. This resulted in tight control over the conditions and quality of storage of the materials used in contact with the collection. 4.4 ENSURING PHYSICAL STABILITY OF OBJECTSAny move usually has time and budget constraints which prohibit full conservation treatment of any but the neediest objects. In planning this Move, it was established that by limiting the transit variables, most minor stability issues could be addressed through packing and crating solutions, and thus, the need for interventive treatments to objects could be reduced. As a result NMAI was able to implement a tiered approach to stabilization treatment that minimized intervention in favor of noninvasive or preventive measures. Even with the best procedures and planning in place the collection was found to have numerous objects with either longstanding or inherent stability problems. In order to safely move these kinds of objects, conservators had to devise a plan to ensure that they arrived at their destination unchanged. 4.4.1 Reassessing Conservation Priorities During the MoveThe pre-move conservation survey was used as the guide for conservation treatment. Once the Move began, the objects that had received a #1 designation, meaning that they required treatment prior to moving, were removed first from the storage vaults. The goal was to stabilize all the #1 priority objects from a particular storage location before the general move of that area started. (The order generally proceeded from geographic locale and then by culture group. ) It was instructive to see, however, that as the Move Conservation team worked through the list of objects that had been given #1 priority by the premove survey crew, a fair percentage were actually recategorized as stable to travel without any intervention, or able to be stabilized with a packing solution. Any savings in time this represented was offset by the significant number of objects that had to be added to the list to receive some sort of treatment. For the most part, these objects were not missed by the survey. Instead, some treatments were added because of damage from handling during the time between the survey and examination by conservators during the Move Project. Other treatments were added to the list because it became evident that predictable damage from handling occurred with certain condition problems. Where possible, stabilization treatment was performed to prevent this type of damage. Overall, the lesson learned was that not all, but many condition problems could be stabilized through good packing, but that any additional or unnecessary handling of fragile objects posed real risks to object stability. In retrospect, the survey looked at the condition of the collection in a general sense. It would have been more helpful if it had been more focused on the kinds of condition problems that would be problematic in moving the collection, such as some types of basketry or other plant fiber objects, damaged featherwork, fragile surfaces, and fragile beadwork. 4.4.2 Scheduling Conservation TreatmentsArtifacts were treated as minimally as possible to achieve stabilization for handling and moving; indepth treatments were done only as necessary. Stabilization actions fell into three levels:

The decision as to which objects would receive treatment and at what level were made by either the Assistant Move Coordinator or the Assistant Manager for Conservation at the Research Branch, often in discussion with the Assistant Move Coordinator for Conservation at the Cultural Resources Center. Communication between conservation managers at the two facilities was important in maintaining the workflow while maintaining confidence that objects were arriving safely at their destination. In addition to the condition of the object, time limitations and lab space were factors in deciding the appropriate level of treatment. 4.4.2.1 Temporary Preventive StabilizationTemporary preventive stabilization was the preferred option. These treatments were not considered permanent, so were not entered into the conservation record, and it was assumed that Cultural Resources Center unpackers would remove Tyvek and Teflon tape unless instructed otherwise. Whenever possible, objects were stabilized at the conservation/cleaning workstation and reintegrated into the move line immediately. Examples of temporary preventive stabilization include the use of cyclododecane on fragile ceramic surfaces, wrapping/binding loose elements with Teflon tape, stabilizing loose beadwork by tying off the end of a loose strand or securing the end of a loose strand with Teflon tape or white cotton thread, and wrapping with Tyvek. Teflon tape was also used to bind a broken area that either could not be readhered or which would travel safely without a more invasive treatment. Teflon was also used to tie fringe or other multiple parts together to aid in safe handling. Where possible, the Photography Department staff took the digital image of such objects before the Teflon tape was applied in order to get the best photograph possible. 4.4.2.2 Minor Stabilization Treatment

If an object could not be protected from further loss or damage during handling and transit using preventive measures, interventive measures were used. Minor treatments were carried out at the conservation/cleaning station in a timely manner to keep objects moving with their associated groups. Examples of these types of treatments include using a drop of adhesive on loose beadwork that could not be tied off, rethreading beadwork, supporting broken feather rachii with a strip of toned Tyvek, and readhering small loose elements. Some repairs to basketry or plant fibers, using wheat starch paste and toned Japanese paper, were also conducted on the move line. These treatments required a short written treatment report entered into the conservation database, and a digital image or drawing but usually no blackand-white or color slide film photography. The tools and materials required to conduct these treatments were kept at the workstations and the use of laptop computers and digital cameras sped the necessary documentation. 4.4.2.3 Treatments in the Conservation LaboratoryStabilization treatments that required more time than could easily be integrated into the workflow at the cleaning station were moved to the Conservation Laboratory. Consideration was given to the amount of time the treatment required and the need to keep the object moving with the rest of its culture group. All such treatments received complete written and photographic documentation. 4.4.3 Preventing and Assessing DamageDespite diligent preventive conservation systems and a fine staff, some damage to collections was considered inevitable with a move of this scale. When damage did occur during the move processes, conservators worked immediately with the staff involved to evaluate what went wrong and to institute changes to prevent similar damage from happening again. Conservation staff documented 217 incidences of major and minor damage to objects during the Move, affecting less than 0. 03% of the objects overall. The number would be even less if instances of damage involving the failure of old repairs were excluded. The vast majority of the damage was caused by handling, and virtually no damage resulted from packing and transport. Damage was documented with digital photographs and a damage report form created specifically for the Move Project. This data is stored in the NMAI Conservation Department at the Cultural Resources Center as hard copies and as electronic files, integrated into the department's standard (non-move) condition and treatment reports and digital image files. 4.5 INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENTIt took considerable time and effort from all staff to coordinate sorting and packing objects based on designated pest treatment methods, and at the same time to keep complete culture groups moving together so they could be efficiently stored together at the Cultural Resources Center. However, the overall cost in time and materials was relatively low when compared to the potential damage to the collection and costs associated with treating an active widespread infestation later. In addition the museum could not afford a shutdown due to an infestation at the Cultural Resources Center because the objects moved from the Research Branch were needed for new exhibits, research, and programs as NMAI prepared for the opening of a new museum on the National Mall in Washington, D. C. in 2004. 4.5.1 Previous InfestationsThe first step in the integrated pest management (IPM) treatment system took place at the Research Branch conservation station, where each object was inspected and old pest evidence such as webbing and casings was completely removed to prevent any confusion between prior and new pest activity. When full removal of evidence of an old infestation was not possible, a tag printed on archival paper was associated with the object, explaining that debris such as frass would still be present. This tag was placed with the object in storage at the Cultural Resources Center for future reference. 4.5.2 IPM StrategiesFive pest management strategies were used during the Move Project: freezing, carbon dioxide, At the Research Branch, conservators associated a label indicating the appropriate pest management procedure with each object. In this way the needs of each artifact were communicated to the people working farther down the move line, as this affected each stage of the process at the Research Branch and the Cultural Resources Center. 4.5.2.1 Low TemperatureFreezing, or more accurately treatment with low temperature, which has been well described in the literature (Carrlee 2003) was the default pest management strategy for all organic materials. Approximately 55% of the collection was treated this way. An exact number is difficult to calculate because freezing, as the default treatment, could not be tracked in the same way other IPM treatments were tracked. NMAI conducted this treatment in accordance with the guidelines recommended by Strang (1992) who plotted temperature with time of exposure to create a graph of the “minimum lethal boundary” necessary to achieve full mortality of insect adults, larvae, pupae, and eggs. Each facility was equipped with a walk-in freezer capable of maintaining −25�C or lower. During the Move the vast majority of the collection was frozen at the Research Branch. Packed boxes of objects were sealed in polyethylene sheet and frozen for one week. Boxes unloaded from the freezer were allowed to acclimate to room temperature overnight and were then packed directly into crates. The objects would not need to be handled again until they were unpacked. 4.5.2.2 Carbon Dioxide GasObjects that were too large to fit in either freezer, and those that could possibly be damaged by a low temperature environment and could not be easily inspected, were treated using a carbon dioxide gas (CO2) environment in a custom-built eight by eight by thirty foot sealed enclosure. Two hundred and seventy-six objects or 0. 03% of the collection received this form of treatment. This procedure and other anoxic environments have been well described in the literature (Burke 1996). Due to space restrictions at the Research Branch, this treatment was carried out at the Cultural Resources Center. While safer for the objects vulnerable to low temperature, the carbon dioxide treatment had several drawbacks. First, it kept objects out of the work flow for up to three weeks as opposed to one week for freezing, and this meant more complex logistical coordination to keep objects from a given culture group together for shelving. The process was also more costly in terms of materials (nine to thirteen gas canisters per run) and labor, for it demanded more maintenance and monitoring by staff. Finally, the environment in the CO2 chamber undergoes a drop in relative humidity and unlike the sealed boxes placed in the freezer, boxes undergoing CO2 treatment were open, removing the protection of a microenvironment. To counteract fluctuations in humidity extra buffering material was added, and no damage was noted. 4.5.2.3 VikaneVikane, or sulfuryl fluoride, was used several times at the Research Branch over the five-year Move for objects such as totem poles and watercraft too large for either the freezer or the CO2 chamber. A total of 506 objects or 0. 06% of the collection were treated with Vikane. The fumigation was done in the trailer used for the regular shipments. A licensed operator sealed the trailer door with plastic and pumped the gas in through the drain. The gas must be flushed out at the end of the treatment with the aid of fans into the open air; thus, this treatment is best done during seasons with stable relative humidity. The treatment is also more appropriate for large or dense objects that react relatively slowly to unfavorable changes in the outdoor environment. During the course of the Move Project it was imperative to plan ahead for these treatments in order to identify and prepare objects with appropriate crates or mounts and maximize the use of space in the trailer. For example, the truck trailer used for the watercraft and house-posts contained four levels of objects and the decking was fitted as it was loaded. Although the application of a Vikane treatment takes 4.5.2.4 Inspection and Bagging and MonitoringObjects that might possibly be damaged by low temperature treatment were flagged at the Research Branch with a label for inspection by conservation upon unpacking. If the object appeared uncompromised, with no recent frass or insect-related damage, and thorough inspection was possible, it was identified as inspected and deemed pest-free. A total of 9, 762 objects or 1. 2% of the collection fell into this group. If the condition was at all questionable, the object was placed in a sealed bag for monitoring over time. A total of 204 objects or almost 0. 03% of the collection were bagged and their condition monitored at the Cultural Resources Center. Because these treatments were tracked with barcode scanning, the registration database could periodically be searched for bagged objects and their respective locations in storage. As these numbers might suggest, as the Move progressed and staff became more familiar with object types and conditions and increasingly skilled at discerning which objects needed to be monitored, fewer items were bagged and more were simply inspected. Pest management treatments were tracked by a system of barcodes and labels, described in detail in Williamson and Kaplan (2001). At the Cultural Resources Center, Registration staff created barcodes for each IPM treatment category so that the strategy used for each object could be quickly and easily entered into the collections database. In this way an ongoing record of CO2, Vikane, inspection, and bagging and monitoring treatments was created. However, it was necessary to reach a compromise between increased efficiency and complete documentation. Due to time constraints, it was not possible to scan barcodes for the vast majority of objects in the collection, which received the default pest management treatments of freezing for organic objects and inspection for inorganic objects. In the end, a combination of institutional memory and electronic data serve to record pest management strategies for individual objects. 5 CONCLUSIONSThe success of the National Museum of the American Indian Move Project was due largely to preventive conservation strategies, control of variables, and flexibility on the part of staff and management. Early planning ensured that a sound structure of preventive conservation procedures and guidelines became universally ingrained in day-to-day work. In turn this allowed the team the flexibility to meet new challenges without compromising the safety of the objects. Conservators found that interventive treatments were needed on a relatively small number of objects and that stabilization treatments required for transit were fewer and less complex than expected. Many of the condition problems that had been expected to need treatment were instead dealt with through creative packing solutions. This allowed the Move to proceed rapidly without compromising the safety of the objects. Communication between the two ends of the Move, the shipping end at the Research Branch in the Bronx, New York, and the receiving end at the Cultural Resources Center in Suitland, Maryland, was crucial. Procedures were refined throughout the project as staff learned through experience, and many innovations were instituted thanks to the creativity and dedication of the staff. Open communication ensured that problems were dealt with quickly, and resulted in the most efficient practices and safest environment for the objects. Good communication throughout the project ensured that preventive conservation strategies remained central to everyone's work in this multifaceted project. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe authors wish to express their gratitude and appreciation to the dedicated and talented staff of the Move team, too many to mention in one paragraph, in New York and Maryland over the entire course of the project. Thanks are also due to NMAI Management: Scott Merritt, Move Manager in New York, Patricia Nietfeld, Supervisory Collections Manager in Maryland, and Marian Kaminitz, Head of Conservation in Maryland. REFERENCES

Arenstein, R. P., C.Brady, N.Carroll, J.French, E.Kaplan, A. Y.McGrew, A.McGrew, S.Merritt, and L. Burke, J.1996. Anoxic microenvironments: a simple guide. Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections Leaflets1(1):1–4. Carrlee, E.2003. Does low-temperature pest management cause damage? Literature review and observational study of ethnographic artifacts. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation42:141–166. National Museum of the American Indian Move Office. 2004. NMAI Move manual. Suitland, Md.: National Museum of the American Indian. Strang, T. K.1992. A review of published temperatures for the control of pest insects in museums. Collection Forum8(2):41–67. Williamson, L., and E.Kaplan. 2001. The role of conservation in the move of collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. Objects Specialty Group postprints. American Institute for Conservation 29th Annual Meeting, Dallas. Washington, D. C.: AIC. 8:106–111. SOURCES OF MATERIALS AND EQUIPMENTCarts—wire, multi-tier, rolling Nexel Industries www.nexel.com Coroplast—corrugated polypropylene board Coroplast Inc. www.Coroplast.com Hanwell Shockbug shock and tilt events datalogger Hanwell Inc. www.hanwell.com/conservation-products.html Hobo Pro relative humidity and temperature datalogger Onset Company www.onsetcomp.com Hot-melt glue (ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer) Low temperature (3M Jet-melt Adhesive 3792LM Q) for paperboard and foam High temperature (3M Jet-melt Adhesive 3748Q) for polypropylene board 3M Corp. www.mmm.com Hot-melt glue applicators 3M Polygun LT Applicator for low temperature 3M Polygun TC Applicator for high temperature 3M Corp. www.mmm.com Kiva-Pak—reusable, collapsible, stackable selfpalletized shipping and storage container system Kiva Plastics Inc. www.kivaplastics.com Minicel—cross-linked polyethylene foam plank Voltek LLC www.voltek.com Nilfisk variable suction vacuum with HEPA filter Nilfisk-Advance America, Inc. www.pa.nilfisk-advance.com/index.html Nylon mini-rivets 27MRF12—two part 27MRM125187 ratcheting action Microplastics Inc. www.microplastics.com Polyester batting Bonded Fibers Midwest www.bondedfibers.com Rings—die-cut polyethylene foam Hibco Plastics, Inc. www.hibco.com. Teflon (polytetrafluoroethylene sheet) film DuPont Co. www.dupont.com/teflon Trays—custom die-cut tab and slot corrugated polypropylene Coroplast Inc. www.Coroplast.com Tri-rod—triangular polyethylene foam backer rod Nomaco Inc. www.nomaco.com Tyvek—high-density spunbonded olefin sheet 1443R and 1025D DuPont Co. www.dupont.com/nonwovens/ap/tyvek.html Vikane—sulfuryl fluoride gas DowAgroSciences LLC www.dowagro.com/ppm/vikane AUTHOR INFORMATIONEMILY KAPLAN received a BA in Studio Art and Art History from the University of Massachusetts Boston in 1984, and an MAC in Art Conservation from Queen's University in 1993. Following graduate school she was a postgraduate fellow at the Smithsonian Center for Materials Research and Education and then at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of the American Indian, Research Branch. She has served as objects conservator at the National Museum of the American Indian, from 1996 to the present and was assistant move coordinator for Conservation from 1999 to 2004 at the Cultural Resources Center. Address: National Museum of the American Indian, Cultural Resources Center, 4220 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD 20746. kaplane@si.edu LESLIE WILLIAMSON received a BA in Art with a minor in Chemistry from Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas in 1988, and an MS in Art Conservation with a major in paintings from the University of Delaware/Winterthur Art Conservation Program in 1992. Following graduate school, she was a postgraduate fellow at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. She served as objects conservator for the National Museum of the American Indian Research Branch in the Bronx, from 1993 to 1999, then as assistant move coordinator for conservation at the NMAI Research Branch through 2004. Address: as for Kaplan. RACHAEL PERKINS ARENSTEIN received a BA in Archaeology and Near Eastern Studies from Cornell University in 1992 and her conservation degree from the Institute of Archaeology at the University of London in 1997. Following graduate school, she completed internships at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum, and the Israel Museum. She served as objects conservator at the Harvard Peabody Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology in Cambridge, Massachusetts and exhibits conservator at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. She was objects conservator and assistant manager for conservation for the National Museum of the American Indian Move Project at the Research Branch in the Bronx, from 2001 to 2004. Address: 1 Rectory Lane, Scarsdale, NY 10583; rachaelarenstein@hotmail.com ANGELA MCGREW received a BA in Anthropology from the University of California Santa Cruz in 1992 and an MA in Anthropology and Museum Studies from California State University at Chico in 2002. She served as a conservation technician and museum specialist at the National Museum of the American Indian Research Branch in the Bronx, from 1996-2004. She is currently associate conservator at the Autry National Center. Address: 4700 Western Heritage Way, Los Angeles, CA 900271462; amcgrew@autrynationalcenter.org MARK FEITL received a BA in Zoology from Miami University in 1994 and an MA in Museum Studies from George Washington University in 1998. He was employed for four and a half years in the Collections Management Department of the National Museum of the American Indian's Cultural Resources as a museum technician and as the Assistant Manager for the move of the ethnology collection. He is currently museum specialist for conservation project support and Native American/Native Hawaiian Museum Services Programs. Address: IMLS, 1800 M St. NW, ninth floor, Washington, DC 20036-5802; mfeitl@yahoo.com

Section Index Section Index |