AMERICAN IMPRESSIONISM, MATTENESS, AND VARNISHINGLANCE MAYER, & GAY MYERS

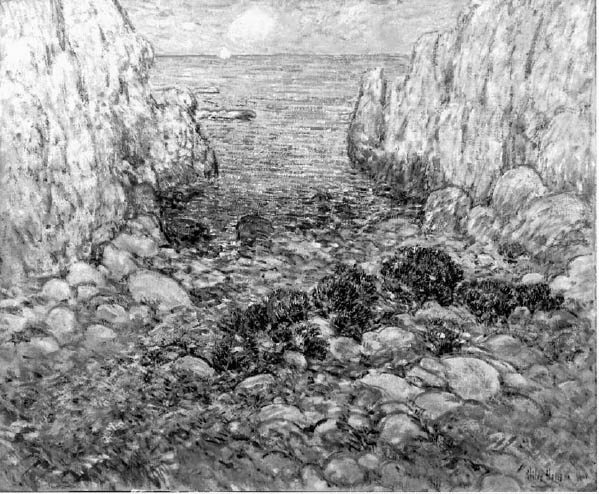

6 VARNISHING PRACTICES OF THE FIRST GENERATION OF AMERICAN IMPRESSIONISTSIt has been possible to compile information about the varnishing practices of several members of the first generation of American painters who came under the influence of French Impressionism. The evidence is sometimes indirect and circumstantial—these were painters who did not talk or write a great deal about technique—and it may not always be possible to make generalizations based upon the limited evidence that is available. Given the caveats discussed above, Childe Hassam, William Merritt Chase, Thomas Wilmer Dewing, and Maria Oakey Dewing (1845–1928) can be documented as having varnished some of their paintings. On the other hand, there is evidence that John Twachtman, Willard Metcalf, and Theodore Robinson preferred unvarnished surfaces on at least some of their paintings. Information about the practices of other American Impressionist painters can be found in Mayer and Myers (1993), and new evidence about the preference for varnish of Dixie Selden and Wilson Irvine, and the nonvarnishing preferences of Charles Ebert, Frederick Frieseke, and Theodore Wendel (1859–1932), is given in the present article. 6.1 CHILDE HASSAM (1859–1935)A letter from Childe Hassam to his dealer in August 1919, in which the artist says that he will not let his flag paintings go anywhere until he has varnished them all that fall or early winter, is an important document because it offers a very rare There is evidence that Hassam wanted at least some of his other paintings to be varnished. A painting dated 1901—Gorge, Appledore (private collection)—was varnished with a medium-thick layer of natural resin varnish, and the artist then completed the painting by applying a number of strokes of paint on top of the varnish layer (fig. 2). The added strokes have the character of artist's paint rather than restorer's paint, outlining and defining rocks and other parts of the landscape in a freely applied manner consistent with the artist's style and technique in the rest of the painting. These strokes prove that the painting had varnish on it while it was still in the artist's hands. Whether or not Hassam actually applied the varnish himself (since varnishing was often done by professional varnishers, from early times until the 20th century), he presumably approved of the fact that the painting was varnished when he applied his final strokes of paint. In fact, the artist's retouching has a considerable amount of varnish mixed in with the paint, so the gloss of the retouching would harmonize with the varnished surface.

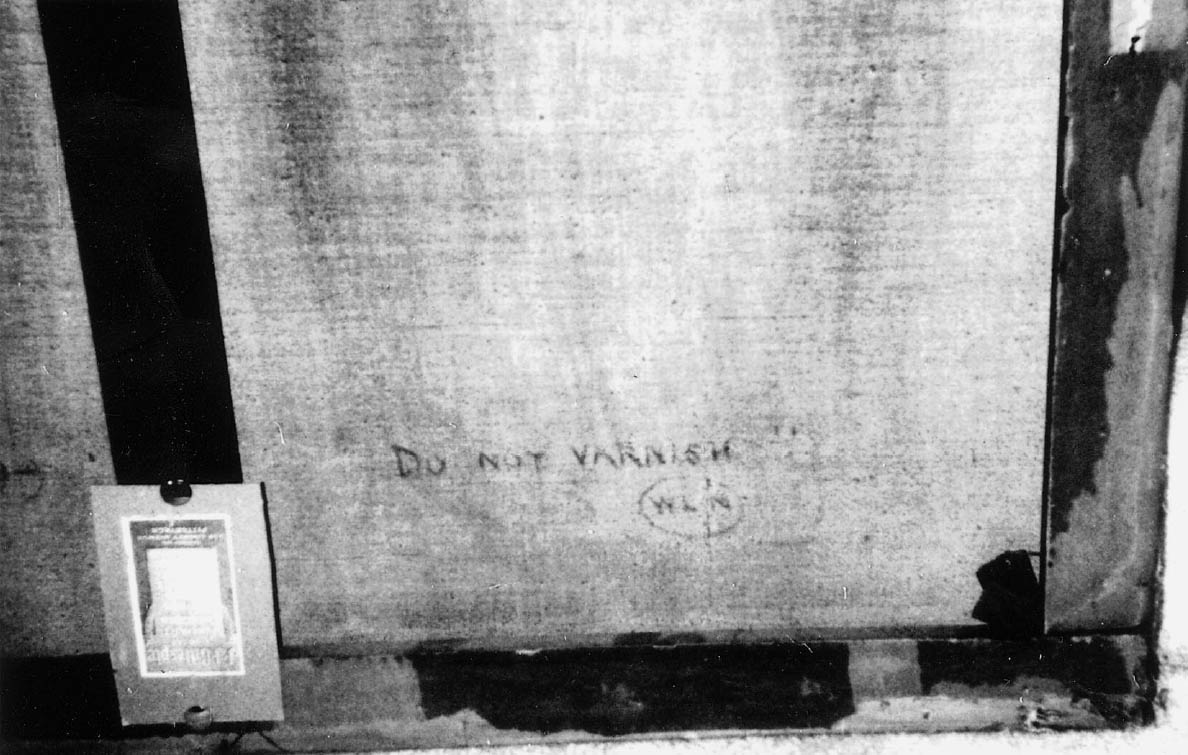

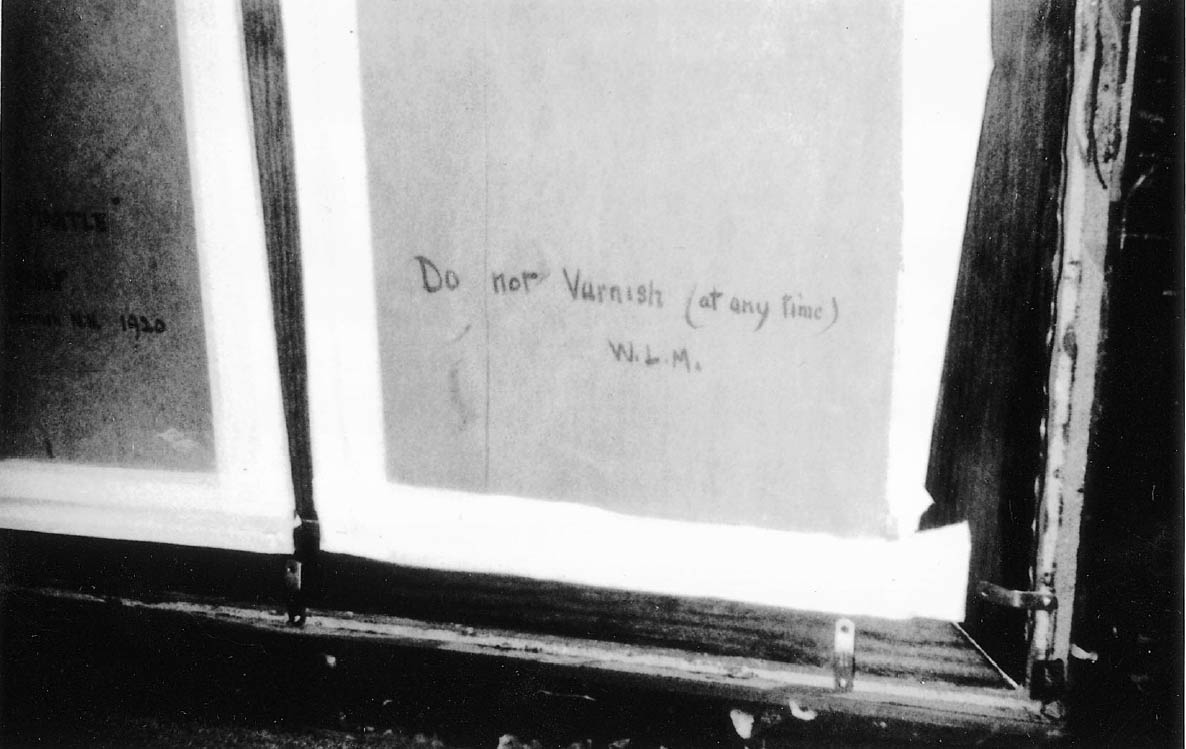

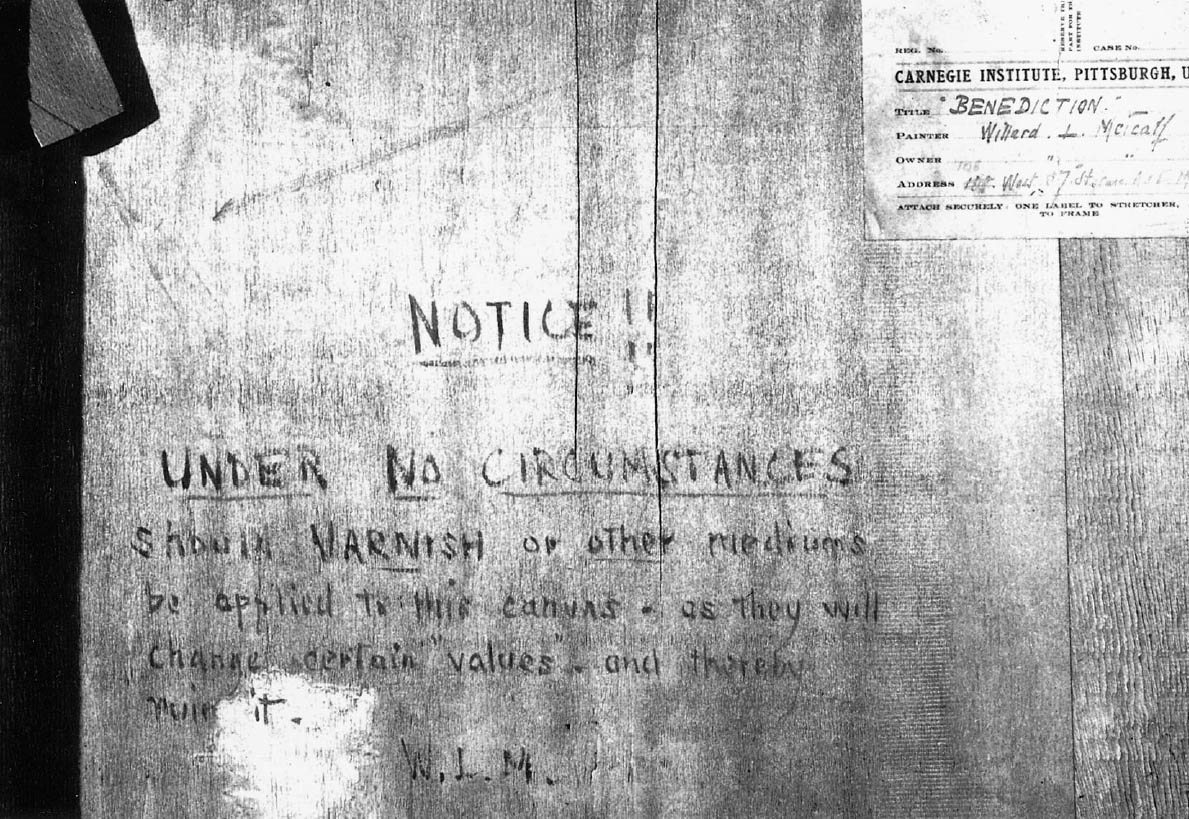

6.2 WILLIAM MERRITT CHASE (1849–1916)The egg tempera painting by Chase described above (sec. 2.2) that was called distemper in 1886 should probably be considered as a separate case from Chase's oil paintings, since it was exhibited at the Water Color Society. Although Chase never converted completely to an Impressionist style, the park scenes that he painted in New York during the 1880s are considered some of the first Impressionist paintings done on American soil. One of these paintings, Lilliputian Boats in the Park (ca. 1888, private collection), has extensive reworking by the artist, including major changes to the principal figure and the painting out of a subsidiary figure. As in the case of the painting by Hassam described above, it is clear that the artist did his retouching on top of a layer of varnish. Old photographs show the painting in its previous state, before the alterations were made. If there was any question about whether the changes were made by the artist or by a later hand, an old installation photograph from the Chase memorial exhibition in 1917 shows the painting in its second (final) state. The natural resin varnish on Lilliputian Boats in the Park could be characterized as being of medium thickness. Another painting by Chase, The Old Road, a sketchy scene on panel done on Shinnecock, Long Island, in Chase's most Impressionistic manner, probably during the 1890s (private collection), had an old, very thin varnish layer. The Old Road appears to have never been treated by a conservator, and the thin layer of natural resin found under a heavy accumulation of grime must have been applied early in the painting's history, although (given the caveats discussed above in sec. 4) it is impossible to determine whether or not the varnish was actually applied by Chase or under Chase's supervision. 6.3 THOMAS WILMER DEWING (1851–1938)Thomas Dewing was a member of “The Ten,” the group of American painters who were among the first to come under the spell of Impressionism, A letter from Maria Oakey Dewing (1845–1928), Thomas Dewing's wife, underscores the point that dealers sometimes had paintings varnished at the request of an artist if and when it was felt that the painting needed it. Maria Oakey Dewing was a painter who collaborated with her husband on a number of projects. She once wrote to her dealer that a potential customer had admired one of her paintings when it was on display in the gallery but told her: “It looked charming but wanted varnish. He begged me to varnish it. Could you do this for me if you are not too busy?” (Dewing n.d.). 6.4 JOHN H. TWACHTMAN (1853–1902)John Twachtman is the best-documented of the American Impressionists in terms of his varnishing preferences. Twachtman began his studies in Munich with Frank Duveneck (1848–1919), who liked medium-rich paint and glossy surfaces (Mayer and Myers 1993). However, Eliot Clark, who knew Twachtman, wrote that beginning about 1890 Twachtmen “deliberately avoided an unctuous, varnishlike effect and would frequently expose his pictures to sun and rain to relieve the pigment of superfluous oil and thus produce a uniform mat or dry surface” (Clark 1979, xx). Twacht-man's son confirmed the story of his father leaving paintings out in the sun and rain, although it is difficult to believe that his paintings would have survived if they were actually allowed to get wet outdoors (see further discussion in Mayer and Myers 1993, 136–37). Many paintings by Twachtman remain unvarnished, and many of them are fairly matte, although paintings by Twacht-man sometimes have glossier passages as well, perhaps attributable to the mastic varnish that the artist was said to have added to his paint. 6.5 WILLARD LEROY METCALF (1858–1925)Many paintings by Willard Metcalf have remained unvarnished, but four recently discovered inscriptions on paintings by Metcalf give much more specific evidence about his objections to varnishing. The dealer John Hagan found an inscription on the reverse of the painting A Summer's Night (1917–18, private collection), which reads, in the artist's hand: “DO NOT VARNISH / W L M” (fig. 3). This is the first case that we knew of in which an American Impressionist did the same as Camille Pissarro when he wrote on the back of a painting at the Mus�e d'Orsay: “Please do not varnish this picture” (Bomford et al. 1990, 101; Callen 2000, 210). Another inscription makes Metcalf's intentions even more clear. On the back of The Enveloping Mantle (1920, private collection), Barbara MacAdam, curator at the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, found an inscription by the artist that reads: “Do not Varnish (at any time)/W. L. M.” (fig. 4). With this inscription, Metcalf is making it absolutely clear that he does not want it varnished at any time; he does not mean, for instance, that it should dry for a year and then it could be varnished. This sentiment is echoed in a third inscription found by conservator Thomas Branchick on the reverse of Hauling Wood (February) (1920, Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy) which adds a prohibition against applying medium as well as varnish:“Do not VARNISH—or at any / time apply any medium / W.L.M.” In a fourth example, Benediction (1920, private collection), the authors found an inscription on the back of the original paneled stretcher in which Metcalf explains his feelings in even more detail (figs. 5, 6). He wrote: “NOTICE!! / UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES / should VARNISH or other

When Metcalf refers to “values”—which he put in quotation marks, as if he knew it had a specific meaning that he was not sure others would understand—he is most likely using the term in the sense of the relative lightness or darkness of parts of a painting. Benediction is a dark evening scene, and on a dark painting, the ways in which different areas might be saturated by varnish can make a very noticeable difference in the values of the dark colors. (Of the three other Metcalf paintings that bear inscriptions, A Summer's Night is also a night scene; Hauling Wood (February) and The Enveloping Mantle are snow scenes that are mostly light in value, but they are similar to the other two paintings in that much of their effect depends upon subtle differences within a limited range of values.) On a dark painting, the reflections from a glossy varnish could also interfere with the reading of the design, but Metcalf's wording makes it seem less likely that his concern was with reflections. Bruce Chambers, who is working on a catalogue raisonn� of Metcalf's works, reported that he knows of no inscriptions about varnishing on any other Metcalf paintings, although other inscriptions may possibly exist but have simply not been noted (Chambers 2002). This point raises the question: why are there inscriptions on only four paintings? It is possible that the artist had a strong opinion against varnishing these paintings in particular, since they have a narrow range of values. However, the sequence of the inscriptions, in which the rhetoric heated up between 1917–18 and 1920, could point toward another scenario in which the artist may have been annoyed by a specific case or cases of paintings having been varnished against his wishes and felt that he needed to use ever stronger language to try to get his wishes carried out. Metcalf's fears about changes in value on Bene-diction also relate directly to the printed labels that were applied by Esther L. Pissarro to paintings by members of the Pissarro family, in which Lucien Pissarro (1863–1944) and Camille Pissarro were said to have worried that if their paintings were varnished against their wishes,“the values were all changed and the picture spoilt—the harm increasing as the varnish darkened” (label illustrated in Callen 2000, 210). 6.6 THEODORE ROBINSON (1852–1896)Theodore Robinson had a more direct link to French Impressionism than most of the other Americans. During the years that he spent in Giverny he developed a close relationship with Monet (made possible because Robinson spoke French), and he continued to exchange letters with Monet after returning to America. Robinson's unpublished diaries (Robinson 1892–96) give a tantalizing glimpse into the working methods of an American disciple of Monet, although the evidence they provide about varnishing practice is in most cases indirect. In fact, Robinson is an interesting case study of the ways in which documentary evidence can be sifted, interpreted, and combined with other evidence gained from the treatment of paintings

Robinson offered opinions about the appearance of Monet's paintings on several occasions. For instance, in 1895 Robinson reported that another man (“Roland”) thought some of Monet's cathedral series “annoying from the amount of pigment, crummy, dry.” Robinson added:“I have felt the same myself, in some of [Monet's] later work.” On a later occasion Robinson amplified upon his conflicting opinions about Monet's cathedrals:“They are bewil-dering at first, but the more one looks, the more of beauty and charm is disclosed; but the painting is so novel that it shocks even the faithful … And I always have found it hard to like the painting, never so sincere and successful as it may be, that is crummy and like masonry … But one gets to like and appreciate the later, wrought-out, elaborate visions” (Robinson 1892–96, entries for December 8, 1895, March 10, 1896). The unusual thickness and “crummy” character of Monet's paint (having a bumpy texture, like crumbs?), more than its matte-ness, seemed to have been the initial obstacle to Robinson's liking Monet's cathedrals. Robinson himself tended to apply his paint much more thinly. In terms of his own painting technique, although Robinson writes about his paintings and his painting process in some detail in his diaries, he never once mentions varnishing any of his paintings (or having them varnished by others). This lack of mention could be seen as a kind of negative evidence. The diaries also make it clear that Robinson was very close to Twachtman and saw him often when he was back in America, probably as often as he saw any other painter. This close association with an American artist who wanted his paintings to be matte is yet another indicator that Robinson could have been influenced by these ideas in his own practice. The diaries demonstrate that Robinson was also closely associated with the painter Theodore Wendel

Robinson once reported in his diary that a New York art critic, writing about the Society of American Artists exhibition in 1896,“refers to the ‘adobe painters’ I suppose in allusion to chalky, dry painting” (Robinson 1892–96, entry for March 26, 1896). The exhibition included paintings by most of the leading American Impressionists as well as some more conservative painters. The exhibition catalog shows that Robinson was among the best represented artists that year, having five paintings on exhibit, while Metcalf had six, Hassam four, and Twachtman two ([Society of American Artists] 1896). Robinson, unfortunately, did not go on to tell us what he himself thought about “chalky, dry painting” on this occasion. In terms of secondary sources that discuss Robinson's technique, Eliot Clark's 1979 book on Robinson contains the statement, “No picture by Robinson should be varnished” (Clark 1979, 32). Although the book was published in 1979, Clark had actually written the manuscript in 1918–20, much closer to Robinson's lifetime. Eliot Clark was too young to have known Robinson before the artist's death in 1896, but he interviewed people who knew him, and Clark was a painter himself as well as our primary source for the information that Twachtman wanted his paintings to be matte, so his opinion carries some weight. A number of paintings by Robinson have never been varnished. When paintings that have been varnished are compared to those that have remained unvarnished, the varnished paintings often show dark strokes of paint that look like they are too dark and do not fit in with the way that the space works in the rest of the picture. This appearance can lead one to suspect that Robinson's paintings suffer from changes in values when they are varnished, exactly as Metcalf had predicted in the long, admonishing inscription on the reverse of Metcalf's painting Benediction. For instance, Robinson's painting Seaside Village (n.d., private collection) was coated with what appeared to be a later varnish when it came to the authors for treatment. In its varnished state, the very dark green and reddish brown strokes in the tree and on the hillside seemed obtrusive, and the space did not work very well (fig. 7). When the varnish was removed, and the darkest strokes became less saturated and consequently more matte, these strokes became lighter in value. In their unvarnished state, the strokes appeared to fit better with the colors and values in the rest of the picture, and when these strokes become less prominent, the recession of space works more logically, especially on the hillside (fig. 8). In another painting, The Little Bridge (n.d., private collection), removing a later varnish made a subtle but noticeable improvement in the appearance of the face of a woman by reducing the contrast between the dark spots of paint that defined her features and the rest of her face, consequently making her facial expression less cartoonlike. The authors have at this point removed varnishes from six paintings by Robinson, often finding that varnish removal makes an improvement in the way that the space in the painting works and keeps individual dark strokes from being too prominent. In none of these paintings was the surface completely If we return once more to written evidence to help interpret the evidence of the paintings themselves, the overwhelming testimony of Robinson's diary is that—in spite of Robinson's qualms about the “crummy” paint application in Monet's cathedral series—he admired Monet more than any other artist and hung on every word of Monet's advice. Robinson himself often compared his work unfavorably to Monet's. He wrote about Monet's paintings vis-�-vis his own: “They are so vibrant and full of things, yet at a little distance, broad tranquil masses are all one sees. They are not spotty or unquiet” (Robinson 1892–96, entry for May 10, 1893). It seems difficult to believe that Robinson would not have carried his admiration of Monet to the point of emulating the unvarnished appearance of Monet's paintings as well. And if we consider the appearance of some of Robinson's paintings—before and after varnish removal—it may not be too much of a stretch to imagine that the paintings, after their varnishes have been removed, look more like what Robinson admired in Monet: less “spotty” and “unquiet.” |