INVESTIGATION, ANALYSIS, AND AUTHENTICATION OF HISTORIC WALLPAPER FRAGMENTSFRANK S. WELSH

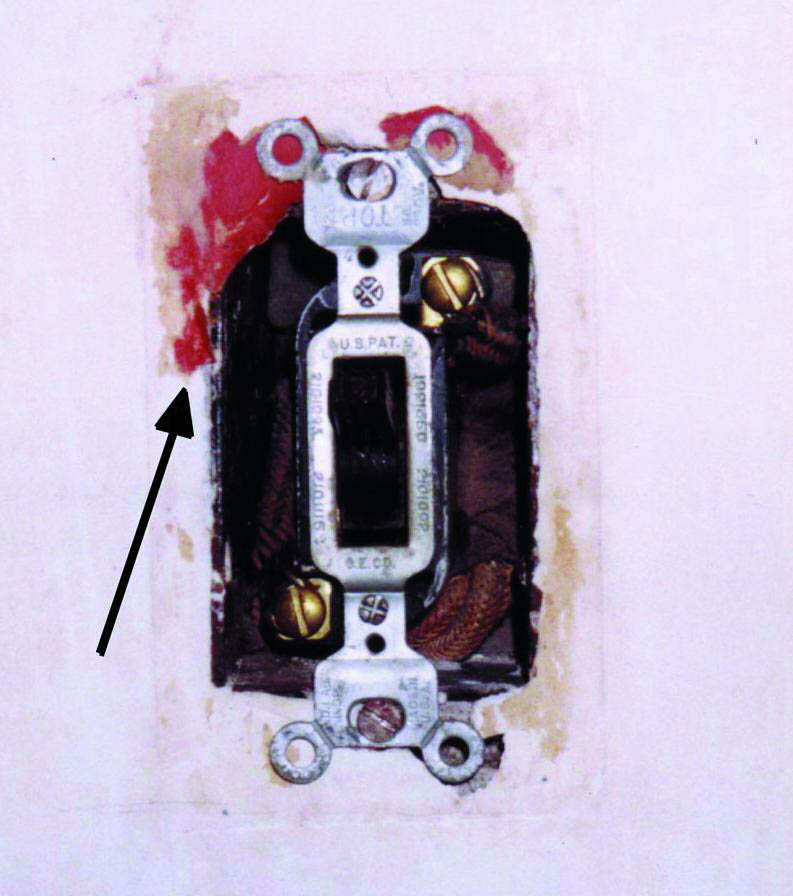

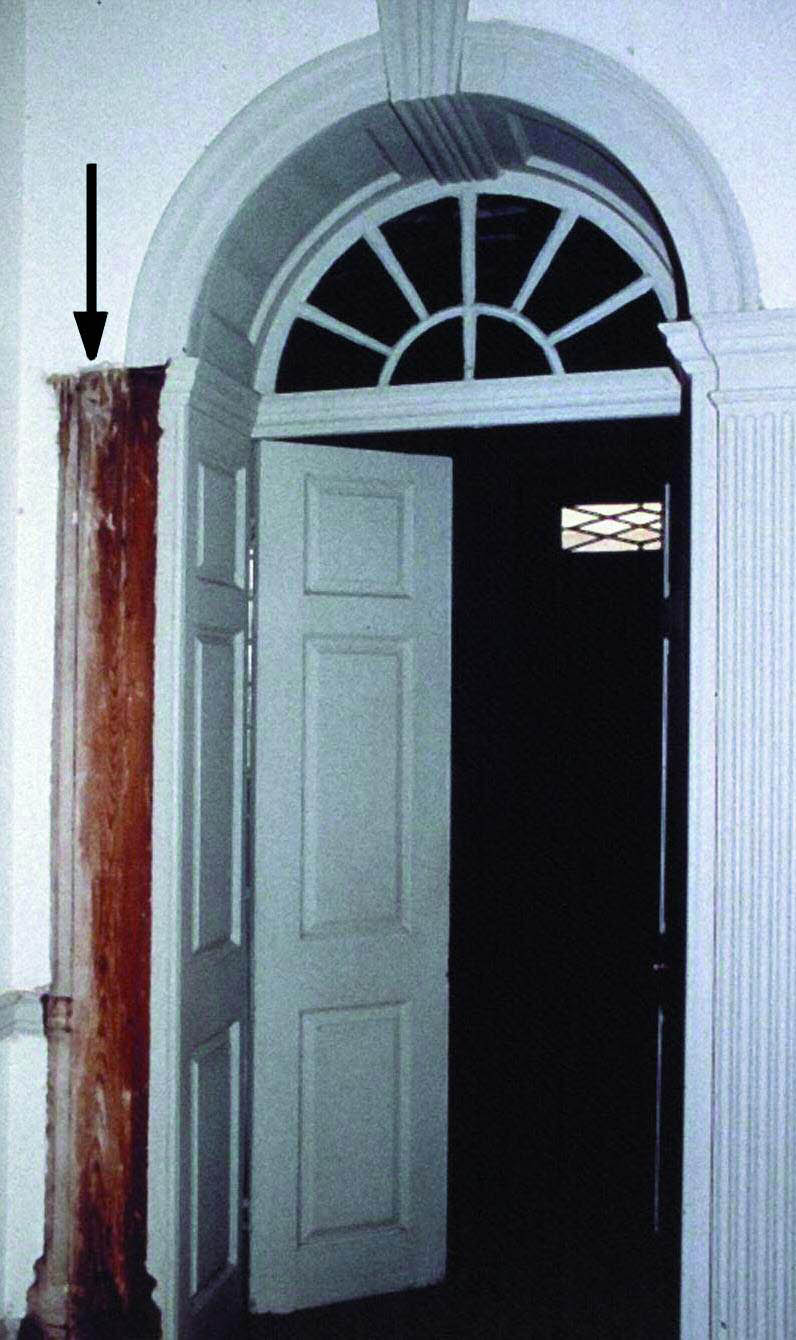

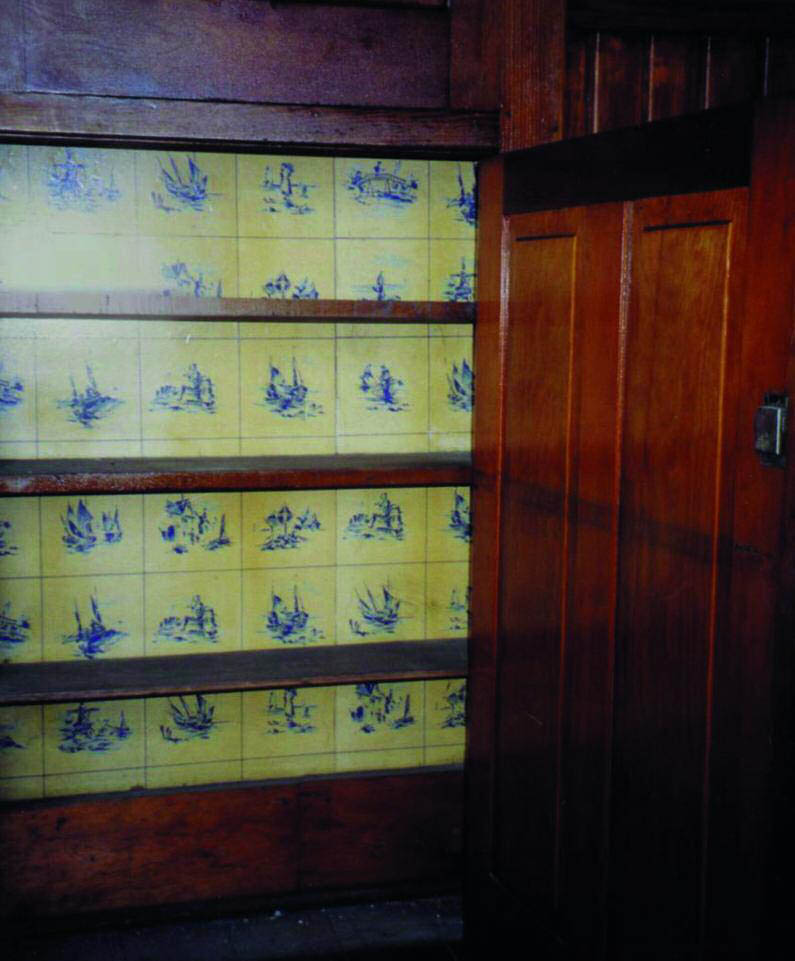

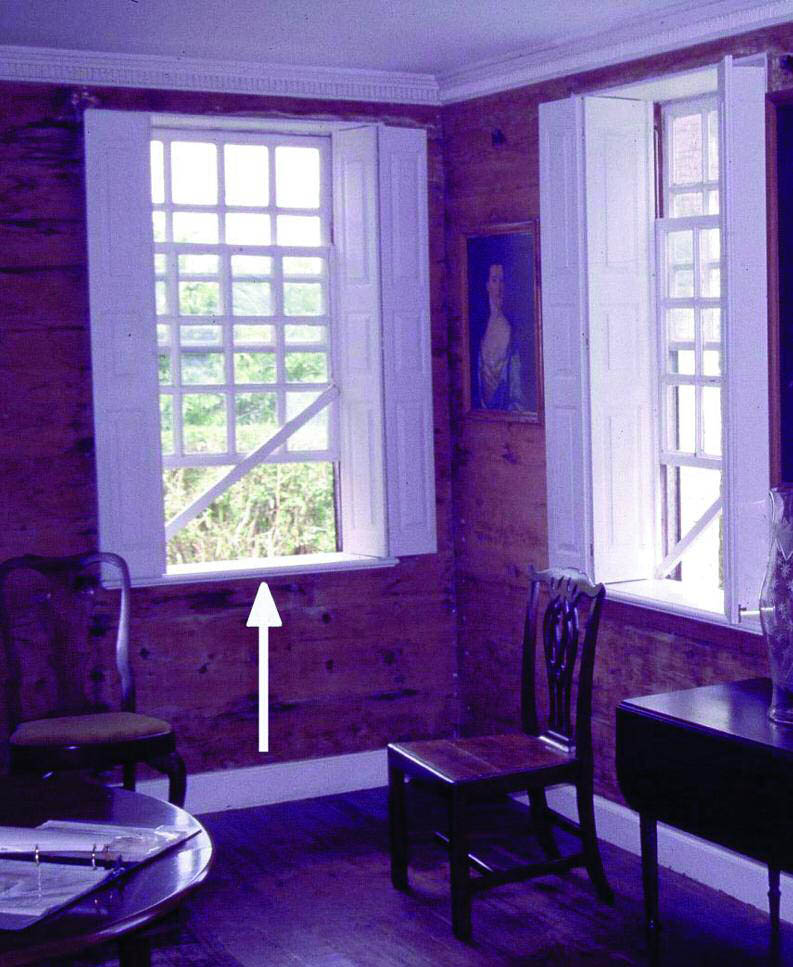

2 SEARCHING FOR EVIDENCEWallpapers, like water-soluble distemper paints, are fragile in nature and can be categorized into a general class of removable decorative finishes. During a redecoration, they may be scraped or washed off the walls with little, if any, trace evidence left behind. Only occasionally did homeowners (or restorers) repaper over existing paper, thereby preserving valuable evidence. Because of the ease and frequency of wallpaper removal, evidence is elusive. Careful attention must be given to identifying and investigating key locations within a house where fragments or fibers of old paper may be found. Examples of such locations include concealed areas behind radiators, light switch cover plates or altered walls, in closets or service passages, inside shutter pockets, and on the top, side, or bottom edges of or behind door and window architraves. The least obvious locations are sometimes the most fruitful. Traces of evidence or even large fragments often remain in these discreet areas and could be overlooked without meticulous examination and repeated sampling. Sometimes the search is as easy as removing a light switch cover plate (fig. 3). At Kenmore (1775) in Fredericksburg, Virginia, a more rigorous investigation was needed to locate two fragments of early wallpaper—one datable to the 18th century and the other to the early-to-mid-19th century.1 In this case, a doorway pilaster was removed, and the fragments were found on a return edge (fig. 4). A similar location bore fruit at Adena (ca. 1807), a mansion designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe for Thomas Worthington in Chillicothe, Ohio, where removal of later door trim revealed a long strip of the original wallpaper encapsulated in ca. 1829 when the doorway was cut through and trimmed out (fig. 5). Closets and wall cabinets may also hide and protect papers that once decorated the walls of a room. At the 1880s home of Paul Laurence Dunbar, renowned African American author and poet, in Dayton, Ohio, the very best surviving evidence was an early-20th-century yellow-and-blue paper patterned to imitate Delft tiles found inside a lower

Sometimes wallpaper can leave a ghost of its pattern, apparent if the paper has been removed, on the bare plaster. During a mid-20th-century restoration of Monticello (1809), under the guidance of Milton L. Grigg, FAIA, a ghosted wallpaper was discovered in the North Octagonal Room. The pattern was so clear it could be compared to a fragment archived in the collection at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, which it matched. That confirmation, coupled with the knowledge that Thomas Jefferson ordered a trellis-patterned paper and complementary border from Paris in 1790, assured restorers and led to the paper's reproduction and rehanging. In 1990, subsequent analysis for color and composition of the paper at Williamsburg led to a second reproduction and rehanging. The pattern of

|