INVESTIGATION, ANALYSIS, AND AUTHENTICATION OF HISTORIC WALLPAPER FRAGMENTSFRANK S. WELSH

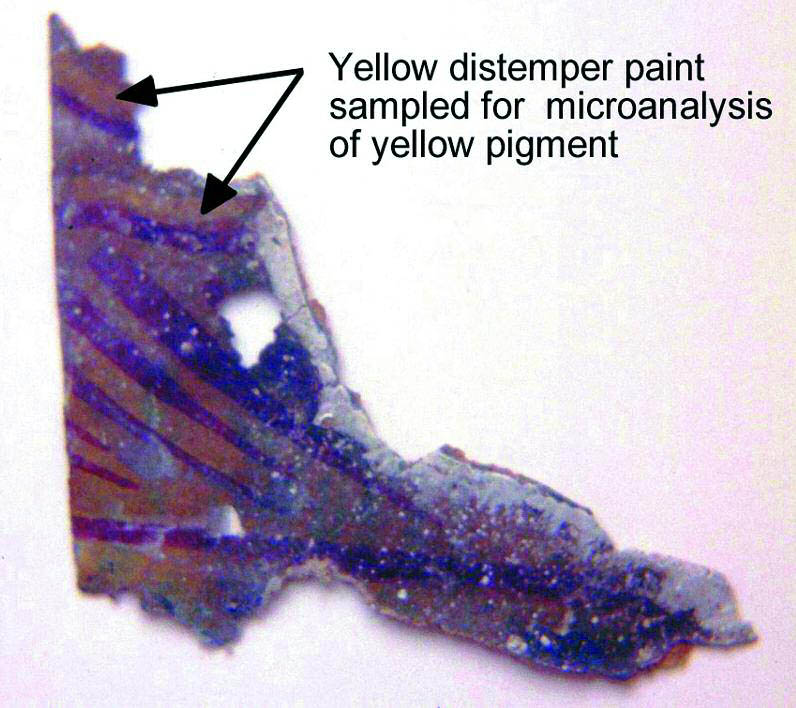

ABSTRACT—Although wallpapers are more ephemeral than painted finishes, they share an equal significance with paint in the investigation of finishes in historic buildings. Ceiling and wall papers were important in a room's overall decorative scheme, but they were often removed as fashion changed. If removed, finding evidence of their use is sometimes as challenging as determining their original colors and patterns. This evidence may include fragments as small as a millimeter or as large as several meters. Whatever the fragment size, microscopical analysis of associated paper fibers and paint pigments coupled with identification of any apparent style or pattern can provide critical information before restoring a room or reproducing a wallpaper. In this article, the process of investigation and analysis is organized into five principal categories that should assist those responsible for the interpretation and restoration of historic surfaces. Numerous examples illustrate the significance of each of these five categories. TITRE—Recherche, analyse et authentification de fragments de papiers peints historiques. R�SUM�— Bien que les papiers peints soient plus �ph�m�res que les rev�tements peints, leur signification est tout aussi importante pour l'�tude des d�cors int�rieurs des �difices historiques. Les plafonds et les papiers peints jouaient un r�le dans l'ensemble du concept d�coratif d'une pi�ce, mais ils ont souvent �t� enlev�s une fois pass�s de mode. Si tel est le cas, il devient alors tout aussi difficile de trouver une preuve de leur utilisation que de d�terminer leurs couleurs ou leurs motifs d'origine. Cette preuve peut �tre un fragment aux dimensions aussi limit�es qu'un millim�tre ou aussi grandes que plusieurs m�tres. Quelle que soit la dimension du fragment, des analyses microscopiques des fibres du papier et des pigments, jumel�es � l'identification de tout style ou motif apparent, peuvent fournir des informations critiques avant de restaurer une pi�ce ou de reproduire un papier peint. Dans cet article, le processus de recherche et d'analyse est organis� en cinq principales cat�gories qui devraient �tre utiles aux responsables de l'interpr�tation et de la restauration des d�cors int�rieurs historiques. De nombreux exemples illustrent la pertinence de chacune des cinq cat�gories. TITULO—Investigaci�n, an�lisis y autenticaci�n de fragmentos de papel tapiz hist�rico. RESUMEN—A pesar de que los papeles tapices son m�s ef�meros que los acabados de pintura, ellos comparten igual importancia con la pintura en la investigaci�n de acabados en edificios hist�ricos. Los papeles tapices para techos y paredes fueron importantes en el esquema decorativo total de un sal�n, pero frecuentemente eran removidos al cambiar la moda. Si fueron removidos, encontrar evidencia de su uso es algunas veces tan retador como determinar sus colores y patrones originales. Esta evidencia puede incluir muestras tan peque�as como un fragmento de un mil�metro o tan grandes como una pieza de varios metros. Cualquiera que sea su tama�o, un an�lisis microsc�pico de las fibras del papel y de los pigmentos de pintura asociados a este fragmento, unido a la identificaci�n de cualquier estilo o patr�n aparente pueden proveer informaci�n muy importante antes de la restauraci�n de un sal�n o de la reproducci�n de un papel tapiz. En este art�culo el proceso de investigaci�n y an�lisis es organizado en cinco categor�as principales que podr�an ser de utilidad a aquellos responsables de la interpretaci�n y restauraci�n de superficies hist�ricas. Numerosos ejemplos ilustran la importancia de cada una de estas cinco categor�as. T�TULO—Investiga��o, an�lise e autentica��o de fragmentos de papel de parede hist�rico. RESUMO—Apesar dos pap�is de parede serem mais ef�meros que os acabamentos pintados, eles partilham um significado id�ntico com a pintura na investiga��o dos acabamentos em edif�cios hist�ricos. Tetos e papel de parede eram importantes no esquema decorativo geral dos quartos e salas mas eram freq�entemente removidos de acordo com a moda do momento. Quando removidos, encontrar 1 INTRODUCTONOver the past two decades, awareness of the extensive use of wallpapers and associated wall coverings in 18th-through mid-20th-century American homes increased dramatically because many historic house restorations included paint and wallpaper analysis. Previously, mid-20th-century restorations of historic interiors often overlooked the cultural and decorative significance of wallpaper evidence. Many of our predecessors removed the original plaster from walls and ceilings and replastered them without recognizing the popularity of wallpapers in the periods they were studying because their primary interest focused on paint colors used on the wood trim. Now the search for the use of wall and ceiling papers is an essential part of the comprehensive finishes investigation of any Colonial, Federal, Greek Revival, Victorian, or early-20th-century building. Frequently, investigation and analysis reveal either trace or fragmentary evidence confirming the use of wallpaper at some time in a building's history, reinforcing the case for wallpapers to share an equal level of significance with paint and other features of interior decoration. Documentary study of historic wallpapers has also enhanced our understanding of their use. By the late 18th century, papers in a wide assortment of styles were available to both the upper and middle classes in urban and rural areas. A hundred years later, they were the standard interior wall finish. Papers were used to add color and pattern to a room or to imitate more expensive materials such as marble, wood grain, textile, and even architectural features. They were integral to the interior decorative scheme. The primary reason for investigating, analyzing, and authenticating historic wallpapers is to verify their use within a particular period of significance at a historic site. Sometimes there is no known wallpaper evidence, and verification of wallpaper's use requires a comprehensive sampling for microanalysis of clues. Search for and analysis of these fragmentary clues are the subject of this article. Written or pictorial documentation can also support wallpaper use, and on rare occasions, large fragments remain intact on the walls or have been removed and stored in collections. Numerous study collections offer a valuable resource for information on patterns and pigments as well as fiber content. Examining papers in these collections also helps refine the dating process, so important in determining when particular papers might have been used. The examination may also increase the accuracy of determining how the colors of a pattern appeared when first manufactured. Two examples demonstrate these points. In the early 1990s, 22 papers in the study collection at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation were analyzed for scholarly purposes before the reissue of the foundation's reproduction wallpapers. One was a yellow, brown, and blue French border dated, based on style, between 1790 and 1820. Microscopical analysis of its fiber composition and paint pigments revealed, however, that its bright yellow distemper paint was tinted with chrome yellow, a pigment not commercially available until the second decade of the 19th century (fig. 1). The other sample, a fragment of an English wallpaper, had been installed in the James Geddy House in the 1960s and was later removed for study. The paper discolored and had a dull brownish appearance where it was exposed to the environment, but a portion at its seam was covered by an overlap that protected the original vibrantly colored verdigris green glaze background (fig. 2). This green background color is one of the best surviving examples of the intended appearance of an 18th-century verdigris pigment resin glaze applied over a painted

To properly understand the significance of a particular wallpaper fragment or evidence of the use of wallpaper within the intended interpretive context, five major avenues of investigation and evaluation must coalesce. By and large, they emphasize the importance of a meticulous search for evidence, a thorough analysis to determine material composition, and a comparative reference to what is known of wallpaper manufacturing processes and, when possible, pattern styles. The five principal points are:

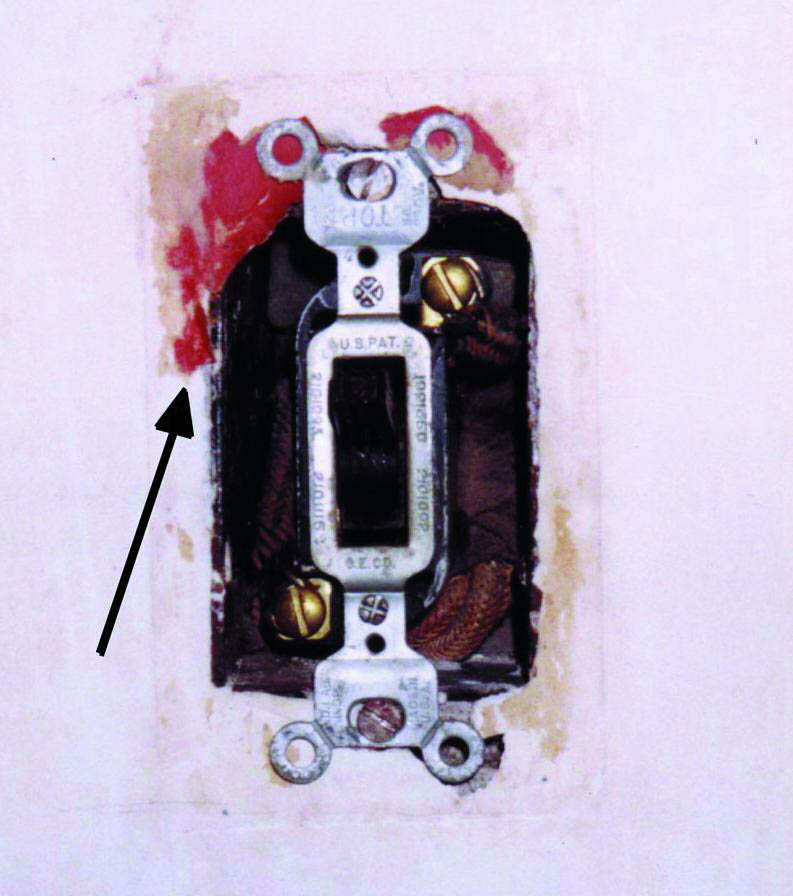

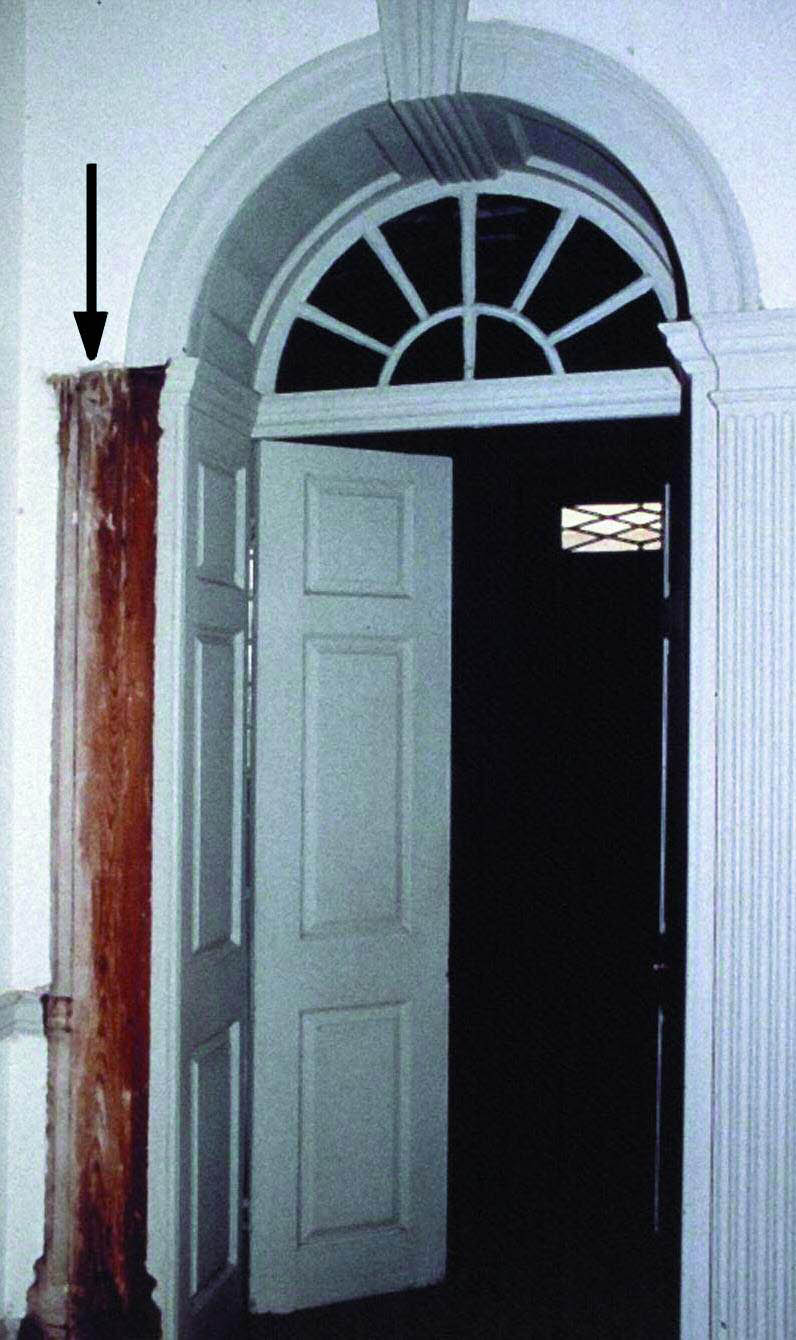

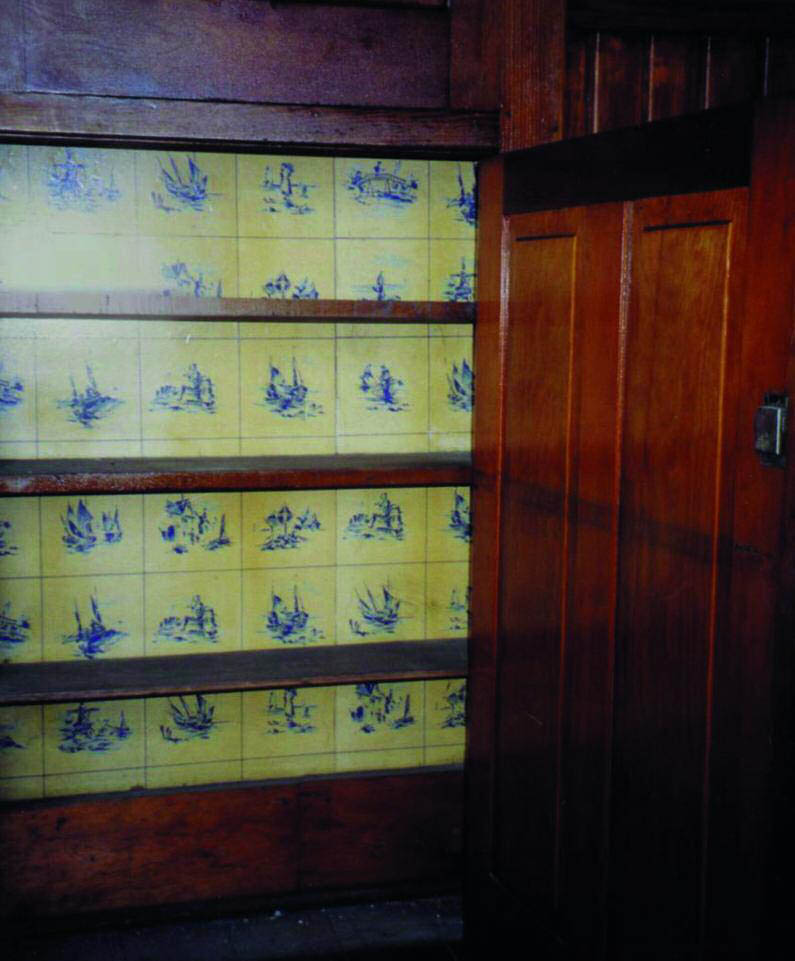

An approach covering all five points of investigation, evaluation, and analysis will more accurately verify wallpaper use, determine pattern and coloration, and authenticate a wallpaper fragment as one made or used within a selected interpretive period. 2 SEARCHING FOR EVIDENCEWallpapers, like water-soluble distemper paints, are fragile in nature and can be categorized into a general class of removable decorative finishes. During a redecoration, they may be scraped or washed off the walls with little, if any, trace evidence left behind. Only occasionally did homeowners (or restorers) repaper over existing paper, thereby preserving valuable evidence. Because of the ease and frequency of wallpaper removal, evidence is elusive. Careful attention must be given to identifying and investigating key locations within a house where fragments or fibers of old paper may be found. Examples of such locations include concealed areas behind radiators, light switch cover plates or altered walls, in closets or service passages, inside shutter pockets, and on the top, side, or bottom edges of or behind door and window architraves. The least obvious locations are sometimes the most fruitful. Traces of evidence or even large fragments often remain in these discreet areas and could be overlooked without meticulous examination and repeated sampling. Sometimes the search is as easy as removing a light switch cover plate (fig. 3). At Kenmore (1775) in Fredericksburg, Virginia, a more rigorous investigation was needed to locate two fragments of early wallpaper—one datable to the 18th century and the other to the early-to-mid-19th century.1 In this case, a doorway pilaster was removed, and the fragments were found on a return edge (fig. 4). A similar location bore fruit at Adena (ca. 1807), a mansion designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe for Thomas Worthington in Chillicothe, Ohio, where removal of later door trim revealed a long strip of the original wallpaper encapsulated in ca. 1829 when the doorway was cut through and trimmed out (fig. 5). Closets and wall cabinets may also hide and protect papers that once decorated the walls of a room. At the 1880s home of Paul Laurence Dunbar, renowned African American author and poet, in Dayton, Ohio, the very best surviving evidence was an early-20th-century yellow-and-blue paper patterned to imitate Delft tiles found inside a lower

Sometimes wallpaper can leave a ghost of its pattern, apparent if the paper has been removed, on the bare plaster. During a mid-20th-century restoration of Monticello (1809), under the guidance of Milton L. Grigg, FAIA, a ghosted wallpaper was discovered in the North Octagonal Room. The pattern was so clear it could be compared to a fragment archived in the collection at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, which it matched. That confirmation, coupled with the knowledge that Thomas Jefferson ordered a trellis-patterned paper and complementary border from Paris in 1790, assured restorers and led to the paper's reproduction and rehanging. In 1990, subsequent analysis for color and composition of the paper at Williamsburg led to a second reproduction and rehanging. The pattern of

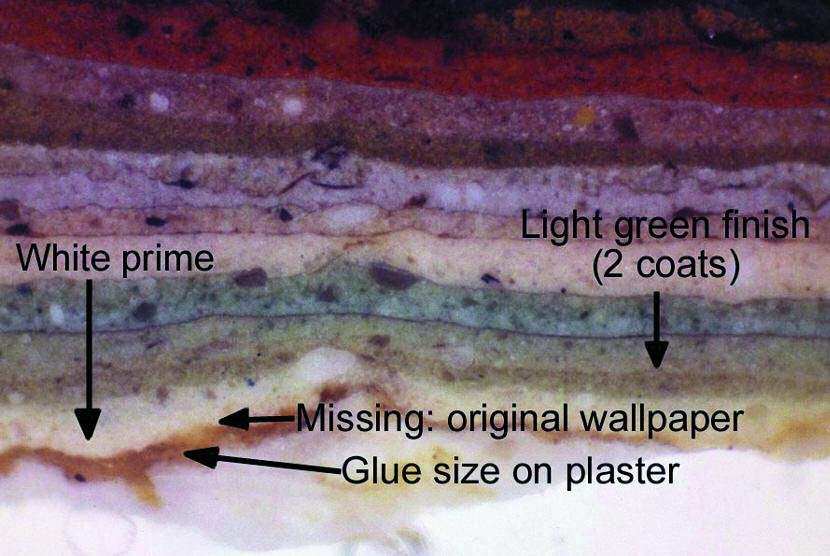

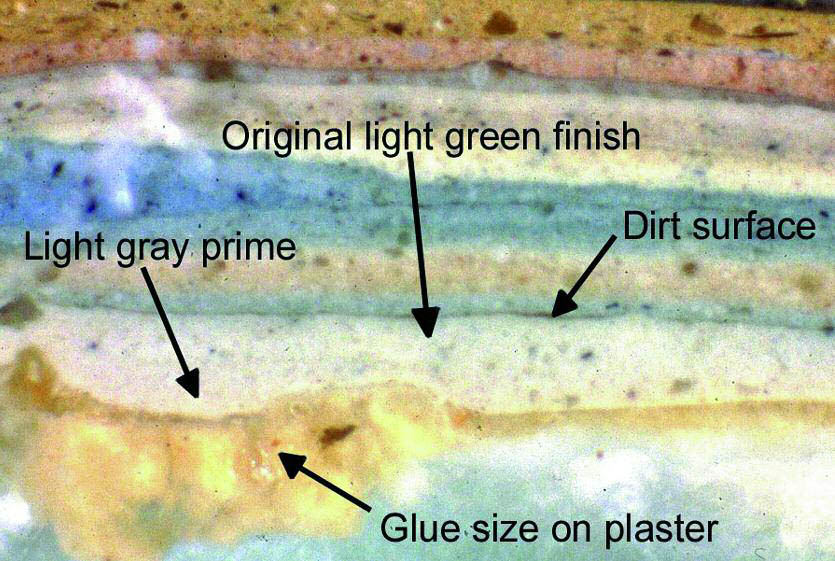

3 EVALUATING THE CONTEXT OF THE PHYSICAL EVIDENCEThe second principal point to consider is an examination and evaluation of the context in which the evidence is found. For a project where the use of wallpaper is unknown, studying the layer structure of the associated coatings and their substrates is essential. If the investigation yields neither paper fragments nor fiber evidence, then the nature of the plaster, size, or even composition of the first and/or second paint layers on the plaster may provide convincing evidence for the use of wallpapers. In 18th-century buildings, the particular paint color used on the wood trim might also suggest the use of wallpaper but is not in itself conclusive evidence of paper use. Conversely, any of these factors could also indicate that the walls were never papered but always painted. One site where paint usage was a determining factor was the Isaiah Davenport House (ca. 1820) in Savannah, Georgia. There the microscopical analysis of paint layer sequence provided substantial evidence of wallpaper use at time of construction. A multi-layered paint cross section from the plaster walls in the first-floor Stair Hall (fig. 8) shows the original glue size on white plaster. The presence of a glue size does not necessarily confirm the use of wallpaper but can suggest its use. In this case, comparative analysis of paint layers on the first-and second-floor Hall walls, combined with analysis of a light green finish, presented convincing evidence that wallpapers were used originally and that the walls were not painted until ca. 1840.2 At Kenmore (1775), in Fredericksburg, Virginia, the paint layer structure contraindicated wallpaper

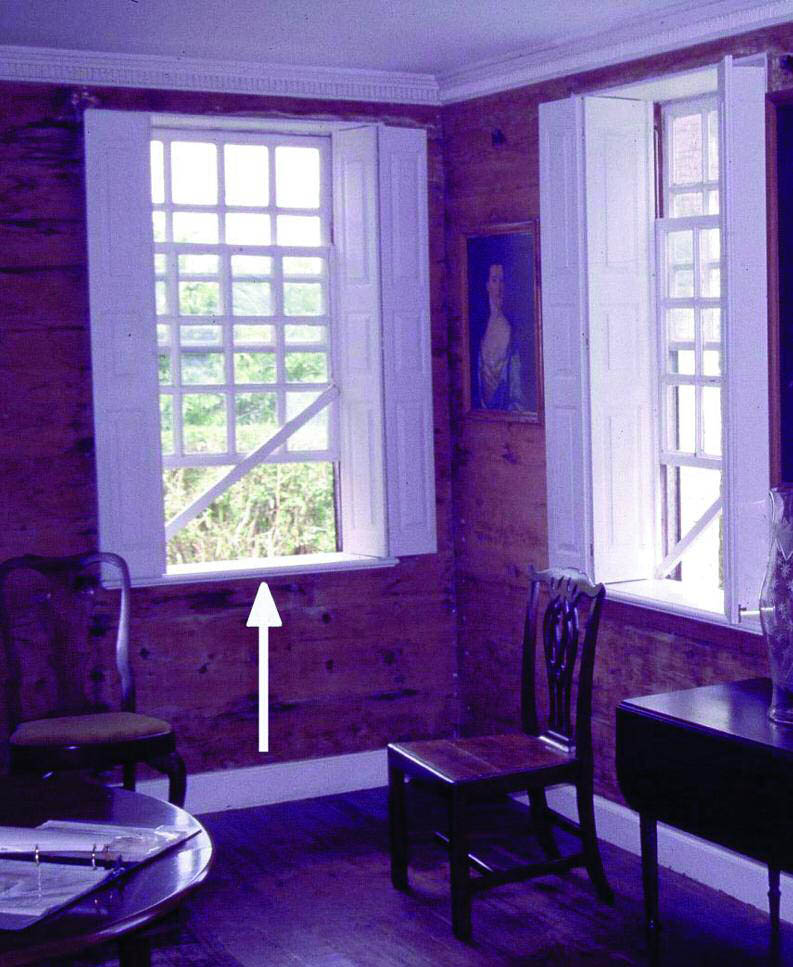

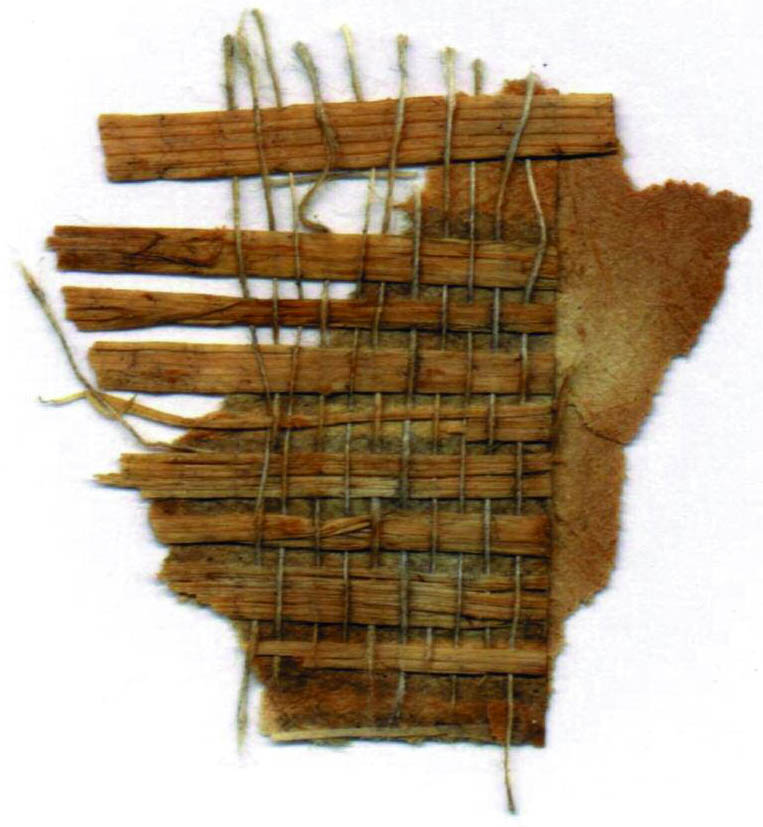

Another example demonstrating the importance of evaluating the physical context is found at Adena, the Latrobe-designed mansion in Ohio. All paint and wallpaper were removed during a 1953 restoration; nevertheless, as thorough as the scraping was at that time, thick areas of accumulated paint remained in the corners and crevices of the moldings around doors and windows. The samples revealed a remarkably extensive decorative palette consisting of 17 different paint colors and evidence of graining and marbling as well as wallpapering. The plaster walls in the six rooms showing evidence of paper were never finished with a white or skim coat of plaster, as were the walls in all other rooms. The rough or brown coat of plaster served as the finished surface, suggesting that the walls were intended to be covered with paper and, consequently, did not require the additional expenditure for a finish coat of white plaster. This interpretation is corroborated by substantial documentary evidence, including an 1821 insurance survey of the house indicating the use of wallpapers and a bill to Thomas Worthington from Thomas & Caldcleugh of Baltimore for the sale of a drapery-patterned paper and border. At the Woodlands (1780s), the Philadelphia country seat of William Hamilton, the first-floor southeast Parlor walls were originally sheathed with large wooden boards much like those at Gunston Hall (1755) in Virginia and Verdmont (early 1700s) in Bermuda. The unpainted board walls in the Parlor at the Woodlands retained many layers of wallpaper. The earliest one had a delicate design on a bright bluish green background.3 It was adhered to a thick linen canvas backing—almost like burlap—that had been nailed, rather than glued, to the board walls (fig. 10). Hanging the paper in this way disguised the imperfections and joints of the sheathed wall and is consistent with the best techniques of wall-paper installation in the period. The context of this paper, on canvas nailed onto unpainted board walls, contributed to the evaluation process and to its authentication as the original finish on the walls.

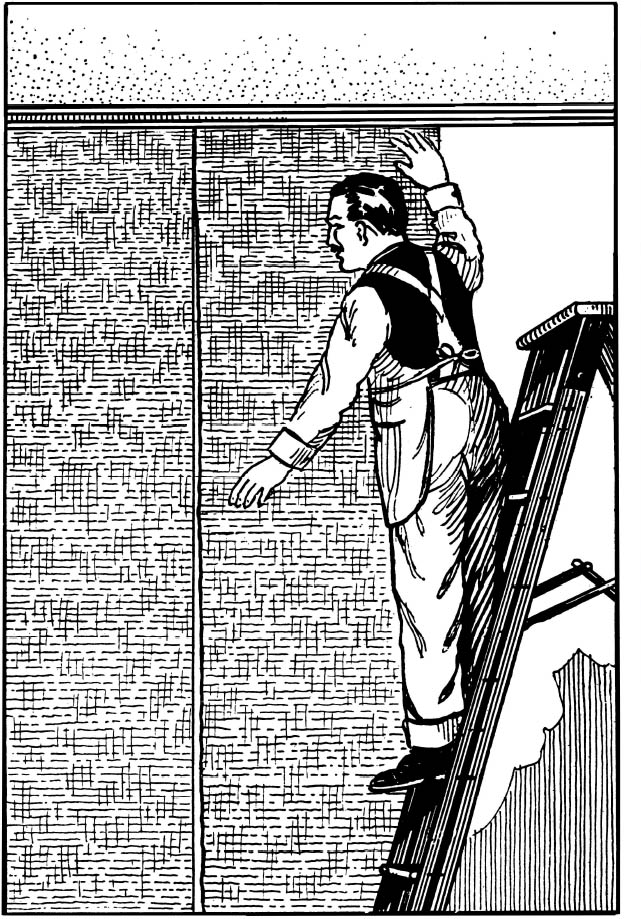

4 IDENTIFYING PATTERN STYLESIf a wallpaper fragment is found and is large enough, the third consideration is identification of the printed or painted pattern. When the style is identified, it can be compared to available information on the popular use of designs in study collections or references like Lynn (1980), which include a host of distinct categories of styles of French, English, German, Chinese, and American wallpapers from the mid-1700s through the early 20th century. This area of study is the domain of wallpaper historians, and the analyst must rely on their research as well as other documentary materials such as photographs, genre paintings, household inventories, or correspondence. Two examples demonstrating the interdependence of historian and analyst are the survival of a photograph in the picture collection of Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, showing the original wallpaper and border in the Drawing Room at Adena (Lynn 1980) and the fact that the French scenic paper “Les Voyages D'Anthenor” (1820–25), used at Piedmont (early 1800s) in Charles Town, West Virginia, and particularly in vogue in the early 19th century, is documented as the work of Joseph Dufour (fig. 11). DETERMINING TYPES OF WALL COVERINGS AND METHODS OF MANUFACTURE If the investigation is successful, yielding large pieces with complete patterns or even tiny fragments with only the suggestion of a pattern, then the fourth aspect of the analysis begins. This is the determination of the types of wall covering and methods of manufacture and pertains not only to the way the paper or covering is made but also to the manner in which the coatings for the patterns are applied. Wall-papers in the 18th century and the early part of the 19th century were printed on handmade paper. The individual sheets of paper varied in size from 56 cm to 81 cm (22–32 in.) square and were usually pasted together to make larger pieces or, in current terminology, rolls. Some papers were made with water-marks, which help with identification, and some of those coming from England between 1714 and 1830 were imprinted with a tax stamp on the reverse side. By 1820, machines were manufacturing “endless” rolls of wallpapers in France. These machines were in use by 1830 in England and by 1835 in America (Frangiamore 1977). In addition, some types of wall coverings are made from distinctive materials. Such papers include ingrains, integrally colored papers, and Lincrusta Walton, a figured, textured, linseed oil–based covering, both popular in the last quarter of the 19th century. Grass cloth, a woven, natural-fiber wallpaper available by the very late 1800s, was used through the early to mid-20th century (Winkler and Moss 1986). A fragment of grass cloth paper was found after a careful search between two abutting doorway architraves of a second-floor bedroom at Cairnwood (fig. 12), the Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania, mansion designed by Carrere and Hastings for John Pitcairn in 1895. The obscure location between the door moldings offered protection from painters' scraping, a find that reinforces the importance of a careful search for evidence. Fabric wall coverings made of canvas were very popular from the late 1890s through the late 1930s (fig. 13) and were typically primed and finished with two coats of oil paint (Vanderwalker 1941). These painted canvas wall and ceiling coverings appeared in

The processes used to apply patterns to the papers have an interesting technological history and are helpful in dating wallpapers. Some 18th-and early-19th-century European and American papers were hand-painted or stenciled, but the majority were block-printed. Block-printing and stenciling might even be combined on one paper, and high-quality papers continued to be block-printed

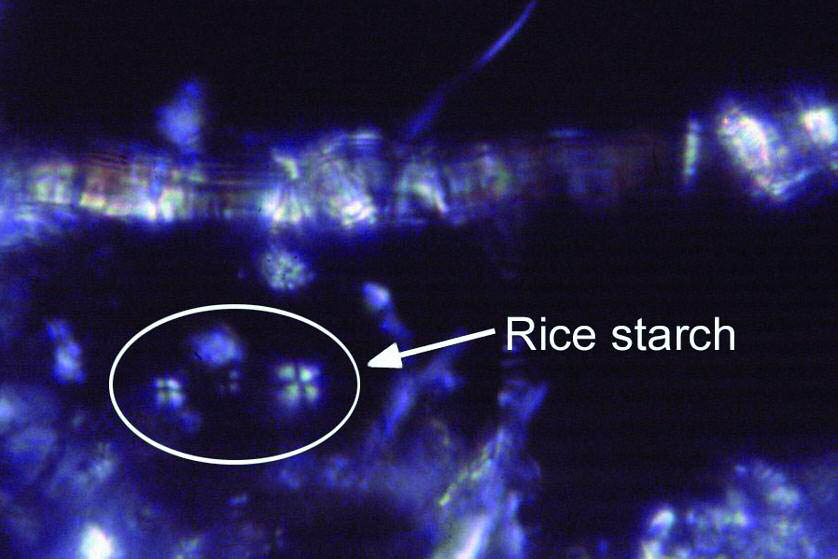

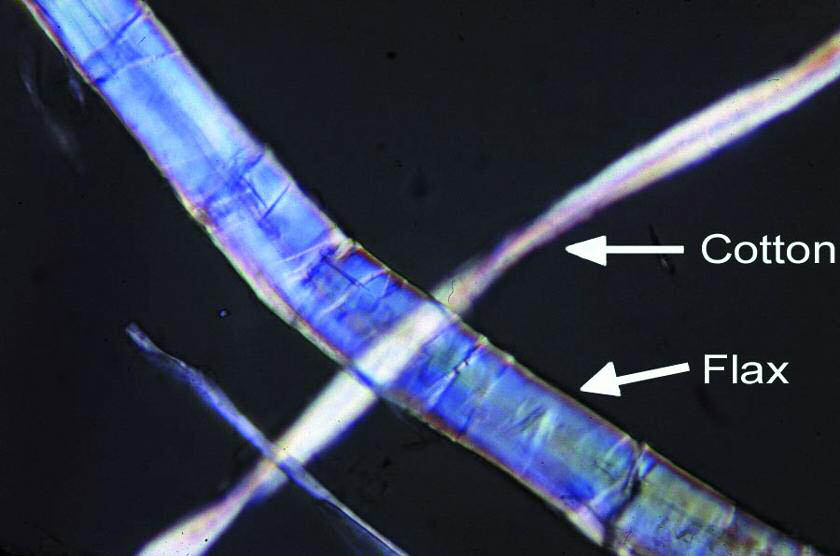

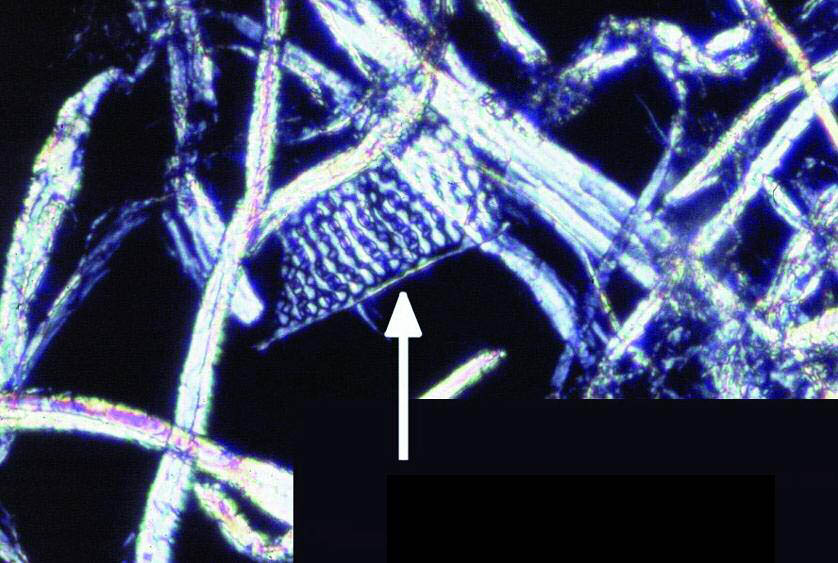

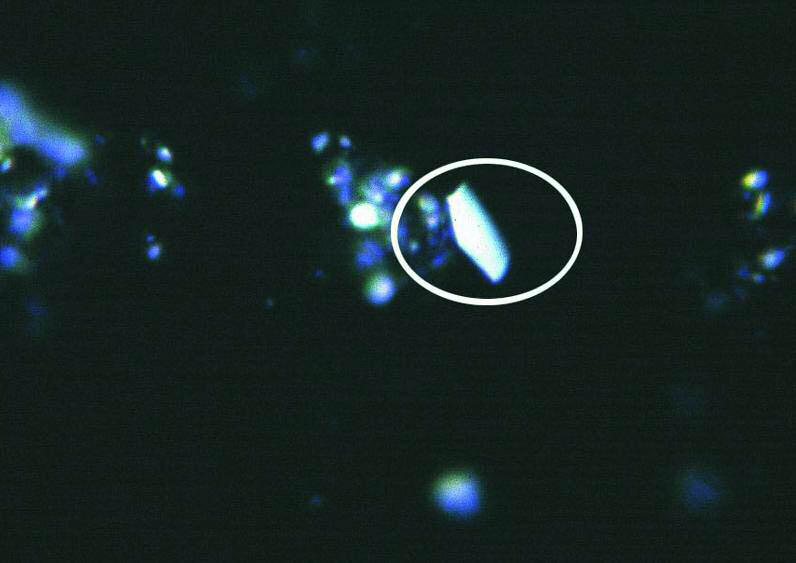

6 ANALYZING MATERIAL COMPOSITION AND EVALUATING ORIGINAL APPEARANCEThe fifth and most important category has two components: microanalysis to determine material composition and the evaluation of original colors and appearance. Fibers can be identified for paper or fabric wall coverings, as can pigments used to make paints and inks used to create patterns. It is also essential to analyze the nature of the binder that holds the paints together. There are extensive technology timelines available for dating paper pulping processes, the material components of wall coverings, and pigments and binding media. Among the The stereomicroscope and the polarized light microscope (PLM) are critical tools used in the analytical process. On occasion, scanning electron microscopy and infrared spectroscopy are also employed. Identifying fibers or pigments not commercially available before specific dates provides critical benchmarks for the process of dating and authenticating papers. PLM is the most useful tool for analysis of these materials. An experienced microscopist can readily distinguish a number of components: paper fibers like cotton, flax, and wood; glue and starch binders; and paint pigments such as calcite, barytes, chrome yellow, and titanium dioxide. Examples from several projects demonstrate the usefulness of fiber analysis. Rice starch in association with flax fibers was identified in an early paper found at Kenmore (fig. 15). Starches were frequently incorporated into the papermaking process as binders (Sindall 1919), and they can be identified microscopically with polarized light because of specific optical characteristics, such as a unique black central cross. At Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site (1842) in Philadelphia, cotton and flax fibers were used in a mid-century green ashlar-patterned wallpaper found intact over a doorway under many layers of paint in the first-floor Hall (fig. 16). Reprocessed rags were the main source for the cotton and flax fibers used in papermaking until ca. 1860, when wood pulp was gradually introduced and adopted by the paper-making industry. A combination of wood pulp, cotton, and/or flax is a variation that is more characteristic of the mid-19th century, when the paper-making industry began the shift between sources. Such variations, like that at the King of Prussia Inn in Pennsylvania, do occur. There, a light brown floral wallpaper was the first of many found on a 19th-century board partition at the 18th-century inn (fig. 17). The pattern style suggests a pre-1850s date, but fiber analysis showed the presence of wood pulp fibers in association with flax, indicating that the paper is post-1860 (figs. 18, 19). Identifying pigments whose initial dates of manufacture are known eliminates some questions of authentication. The most notable early-19th-century pigments are chrome yellow and barytes, which were found in wallpapers at Gunston Hall and Kenmore and in the collections at Colonial Williamsburg. Removal of overdoor pediments in a principal first-floor room with original board walls at Gunston Hall revealed many very small wallpaper fragments showing a partial pattern block-printed in red and yellow

Another pigment with a proven chronology is titanium dioxide (white), one of the most widely

Sometimes, though, dating pigments is more fluid than fixed. The entry on chrome yellow in Gettens and Stout (1966, originally published in 1942), one of the most widely used references for pigment information, states that the pigment was known in 1809 but was not in commercial production until 1818. However, Fodera et al. (1997, 106–7) cite an 1812 advertisement for chrome yellow in Baltimore. Research continues to refine our understanding of the history of pigment and fiber production and availability. Publication of that research is a valuable component of materials analysis. Other materials identified under the microscope also offer clues to a paper's history. One of these is shellac, a varnish coating used in the mid-to-late 19th and early 20th century to protect papers and make them washable, especially those used in bathrooms (fig. 25; see also fig. 6). A recipe for “washable wallpaper varnish” appears in McIntosh (1911, 394): “Shellac or stick lac 30 lb., borax 30 lb., water 20 gallons. Boil til dissolved, filter; when applied on wallpaper with a smooth brush it dries with a fine gloss. Two coats are given.” Shellac generally yellows with age, adding to the challenge of evaluating colors. Other culprits are dirt and grime, which accumulate on wallpaper surfaces and cause severe discoloration. Dirt and grime present a special problem if the wallpaper is a candidate for reproduction. Before embarking on the reproduction process, a thorough examination of the fragment and a search for protected areas are necessary to visually match pattern colors as closely as possible. The 18th-century English floral wallpaper from the study collection at Colonial Williamsburg Foundation discussed in section 1 (see fig. 2) illustrates this point. Another example is from a bathroom in an early-20th-century suburban Philadelphia residence where the original 1939 Sanitas was discolored by accumulation of nicotine (see fig. 14), but cleaning a tiny portion of paper preserved under a light fixture revealed the original color. For a wall covering such as plain painted canvas, a color match of the fabric itself may not be essential; however, the original sample can be analyzed for material composition and thread count. This information

7 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONSBy covering the points suggested in the five-step investigation and evaluation process, experienced conservators and preservationists can confidently recommend and undertake plans for interpretation of different periods at historic sites. Because a thorough on-site investigation often reveals wallpaper fragments, microscopical analysis for fiber and pigment composition can contribute important information to the multidisciplinary effort associated with restoration projects. When wallpapers and fabric wall coverings meet all the criteria of appropriate context, style, manufacturing processes, and composition for the period under study, they become authenticated candidates for reproduction. One such example is a large piece of old wallpaper from the Jonathan Hale House in Bath, Ohio, built in 1826 (fig. 26). A small section of a board from an original partition was discovered in a rebuilt fire-place hearth. The board has several layers of paint on one side and wallpaper on top of the paint (fig. 27). The floral style of the pattern was very popular in the mid-1800s, especially for bedrooms (Winkler 2000). Cotton and flax constitute the paper's fiber content; they were the primary paper fibers until about 1860, when wood pulp fibers were introduced. The paper is machine-made, a process developed in the 1830s, and the four thin-bodied, distemper colors of the pattern—white and pink roses with green leaves and brown stems—were roller-printed onto a light beige ground paint. The green paint used to print the leaves

The accumulated findings demonstrate the value of the five principal categories of comprehensive investigation and analysis of wallpapers and wall coverings. Combined, these findings suggest a date for the paper between the mid-1840s and 1860. This date fits within the 1850–70 period of historic significance chosen by the museum for the interpretation of the house. The colors and chronology of paint layers under the wallpaper on the salvaged board were compared to other collected paint evidence from all rooms in the house to determine the original location of the board. The wallpaper was thus authenticated, and, with carefully matched colors, it can be reproduced and rehung in its original location. Reproduction of the wallpaper will ultimately be facilitated by the fact that the paper sample shows a full repeat of the pattern. Even if a complete historic wallpaper pattern cannot be determined because the evidence is incomplete or circumstantial, the indication of wall-paper use is valuable in and of itself, as it contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of how an interior space was decorated. Authenticated and accurately reproduced wallpapers have the potential to dramatically affect a visitor's experience of a historic space and also offer opportunities for study for both laymen and professionals. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSI would like to thank those who contributed to the research and analysis necessary for this project. The Barra Foundation, for funding Frank S. Welsh's 1990–91 analysis of 22 papers in the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation collection, undertaken for research purposes prior to the reissue of the Colonial I would also like to express my special gratitude to Walter C. McCrone, chemical microscopist, McCrone Research Institute, Chicago, Illinois. Dr. McCrone's death in July 2002 was an enormous loss to me as well as to the many people who came to know him over his long and extraordinary career. Dr. McCrone's genius and foresight, coupled with his unyielding dedication and enthusiasm for the life he enjoyed and the work that he embraced with the polarized light microscope, created a world of inspiration that was admired by and contagious to many people. The 20 years that I knew and worked with Dr. McCrone were enriched beyond measure by the gifts of his teaching and mentoring. NOTES1. Between 1996 and 1998 more than 275 samples were taken from 11 rooms at Kenmore for micro-scopical analysis as part of a comprehensive investigation of historic paint and wallpaper finishes. More than 33 wallpaper samples were found in the form of either fibers or fragments, some painted, some not. More than 53 preparations were analyzed with polarized light microscopy (PLM) for pigment, fiber, or particle (i.e., mold or starch) characterization. The analysis is documented with more than 90 photo-micrographs. Copies of the report (Welsh 1998) are available at Kenmore Plantation and Gardens in Fredericksburg and at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia. 2. At Davenport House, microscopical analysis of the pigments used to make the light green finish on the first-floor Hall walls identified white lead, calcium carbonate, barytes, and chrome green, which was not commercially available until after 1820. Chrome green was made by combining barytes, China clay, and chrome yellow with Prussian blue. The result is a very homogeneous mixture that appears microscopically as a green smear, and it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between the blue and yellow pigment particles (Gettens and Stout 1966). This characteristic is evident on the chrome green pigment from Davenport House. 3. Polarized light microscopical analysis of the Wood-lands Parlor wallpaper's blue-green ground paint revealed that it was tinted with green verditer, a basic copper carbonate. REFERENCESBrowning, B. L.1969. Analysis of paper. New York: Marcel Dekker. Feller, R. L., ed.1986. Artists' pigments: A handbook of their history and characteristics, vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. FitzHugh, E. W.1997. Artists' pigments: A handbook of their history and characteristics, vol. 3. New York: Oxford University Press. Fodera, P. L., K. N.Needleman, and J. L.Vitagliano. 1997. The conservation of a painted Baltimore sidechair (ca. 1815) attributed to John and Hugh Finlay. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation36(3):183–92. Frangiamore, C. L.1977. Wallpapers in historic preservation. National Park Service Publication 185. Washington, D. C.: National Park Service. Gettens, R. J., and G. L.Stout. 1966. Painting materials: A short encyclopaedia. 2d ed. New York: Dover Publications. Harley, R. D.1982. Artists' pigments, c. 1600–1835. 2d ed. London: Butterworth Scientific.

Hoskins, L., ed.1994. The papered wall: History, pattern, technique. New York: Harry N. Abrams. Lynn, C.1980. Wallpaper in America from the seventeenth century to World War I. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., for the Barra Foundation. McCrone, W. C.1997. A history of titanium dioxide pigments. Microscope45(2):41–46. McCrone, W. C., and J. G.Delly. 1973. The particle atlas. 2d ed. Vol. 2 of The light microscopy atlas. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ann Arbor Science Publishers. McCrone, W. C., J. G.Delly, and S. J.Palenik. 1979. The particle atlas. 2d ed. Vol. 5 of The light microscopy atlas and techniques. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ann Arbor Science Publishers. McIntosh, J. G.1911. The manufacture of varnishes and kindred industries. Vol. 3 of Spirit varnishes and spirit varnish materials. London: Scott, Greenwood & Son. Nylander, R. C., E.Redmond, and P. J.Sander. 1986. Wallpaper in New England. Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities. Roy, A.1993Artists' pigments: A handbook of their history and characteristics, vol. 2. New York: Oxford University Press. Sindall, R. W.1919. The manufacture of paper. New York: D. Van Nostrand Co. Vanderwalker, F. N.1941. Interior wall decoration. Chicago: Frederick J. Drake & Co. Welsh, F. S.1998. Kenmore: Microscopical paint and color analysis. Welsh Color & Conservation, Bryn Mawr, Pa. Winkler, G. C.2000. Personal communication. Design historian, Philadelphia. Winkler, G. C., and R. W.Moss. 1986. Victorian interior decoration: American interiors, 1830–1900. New York: Henry Holt and Co. FURTHER READINGAckerman, P.1923. Wallpaper: Its history, design and use. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co. Bivins, J., and J. T.Savage. 1993. The Miles Brewton House, Charleston, South Carolina. Magazine Antiques143(2):294–307. Chappell, E.1995–96John Perry and Williamsburg's wallpaper. Colonial Williamsburg: The Journal of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation28(2):38–41. Cohn, Marjorie B., ed. 1981. Wallpaper conservation: A special issue. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation20(2): entire issue. Entwisle, E. A.1954. The book of wallpaper: A history and an appreciation. London: Arthur Barker. Frangiamore, C. L.1974. Rescuing historic wallpaper: Identification, preservation, restoration. American Association for State and Local History Technical Leaflet 76. History News29(7). Hitch, N. V., and C. J.Lugg. 2002. Wallpaper documentation and reproduction at Adena: The Worthington Estate. APT Bulletin33(2–3):57–64. Hunter, D.1943. Papermaking: The history and technique of an ancient craft. New York: Knopf. Jacobsen, H. N.1994. Hugh Newell Jacobsen, architect: Recent work [1988–93]. Rockport, Mass.: Rockport Publishers, for the American Institute of Architects Press. Kelley, R.1990–98Wallpaper Reproduction News. vols. 1–9. Library of Congress. 1968. Papermaking: Art and craft. Washington, D. C.: Library of Congress.

Long, T. P.1991. The Woodlands: A “matchless place.” Master's thesis, University of Pennsylvania. Maddox, H. A.1945. Paper: Its history, sources and manufacture. London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons. McClelland, N.1924. Historic wall-papers: From their inception to the introduction of machinery. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co. McCrone, W. C.1982. The microscopical identification of artists' pigments. Journal of the International Institute for Conservation—Canadian Group7(1–2):11–34. Nylander, R. C.1983. Wallpapers for historic buildings. Washington, D. C.: Preservation Press. Nylander, R. C.1995. Prestwould wallpapers. Magazine Antiques147(1):168–70. PAHS and DCHS. 1983. Sautter House five: Wallpapers of a German-American farmstead. Papillion, Nebr.: Papillion Area Historical Society and the Douglas County Historical Society. Parham, R. A., and R. L.Gray. 1982. The practical identification of wood pulp fibers. Atlanta, Ga.: TAPPI Press. Pritchard, M. B., and W.Graham. 1996. Rethinking two houses at Colonial Williamsburg. Magazine Antiques149(1):166–75. Sindall, R. W.1910. Paper technology. London: Charles Griffin & Co. Snodgrass, A., and E.Farrell. 1989. The technical examination of an 18th-century wallpaper from the Wentworth-Coolidge Mansion, Portsmouth, New Hampshire. In The Book and Paper Group annual of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. Washington, D. C.: AIC. 8:67–73. Welsh, F. S.1988. Piedmont: Microscopical paint and color analysis. Welsh Color & Conservation, Bryn Mawr, Pa. Welsh, F. S.1992. Prestwould wallpaper collection. Welsh Color & Conservation, Bryn Mawr, Pa. Welsh, F. S.1994. Belle Meade: Microscopical paint and color analysis. Welsh Color & Conservation, Bryn Mawr, Pa. Welsh, F. S.1998. Verdmont wallpaper. www.welshcolor.com/wallpaper (accessed 7/02). Welsh, F. S.1999a. Isaiah Davenport House: Microscopical paint and color analysis. Welsh Color & Conservation, Bryn Mawr, Pa. Welsh, F. S.1999b. Oldfields: Microscopical paint and color analysis. Welsh Color & Conservation, Bryn Mawr, Pa. Welsh, F. S.2001. Dunbar House: Microscopical paint and color analysis. Welsh Color & Conservation, Bryn Mawr, Pa. Welsh, F. S.2002. Adena: Microscopical paint and color analysis. Welsh Color & Conservation, Bryn Mawr, Pa. AUTHOR INFORMATIONFRANK S. WELSH is a conservation microscopist and president of Welsh Color & Conservation, Inc., a consulting firm specializing in the investigation and analysis of historic architectural coatings. He holds a degree from West Chester University and certificates for advanced study at the McCrone Research Institute in Chicago, at Drexel University, and at the University of Pennsylvania. He has served as a visiting faculty member of the Preservation Institute: Nantucket, a summer program in historic preservation sponsored by the University of Florida at Gainesville. He also served as adjunct assistant professor in the Master of Arts in Historic Preservation Program at Goucher College in Baltimore, Mary-land. Awarded a Charles E. Peterson Fellowship for advanced study from the Athenaeum of Philadelphia in 1992–1993, he undertook research on early American paints, colors, and pigments, and wrote a chapter, “The Early American Palette: Colonial Paint Colors Revealed,” for the book Paint in America, published by Preservation Press. His work on historic sites has been featured in both scholarly and popular periodicals, such as Microscope, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, APT Bulletin, Architectural Record, Progressive Architecture, Magazine Antiques, and Colonial Homes. He has written and lectured extensively, drawing on 30 years of experience in the field and work on over 1,400 restoration projects.

Section Index Section Index |