PRIOR REPAIRS: WHEN SHOULD THEY BE PRESERVED?JEAN D. PORTELL

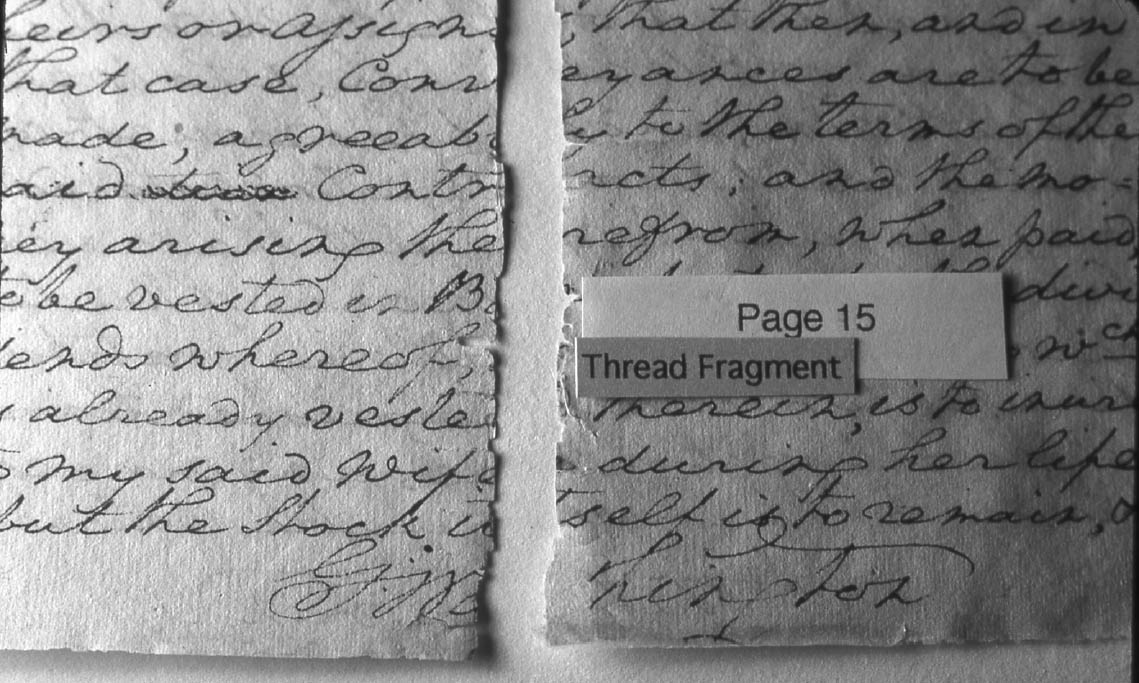

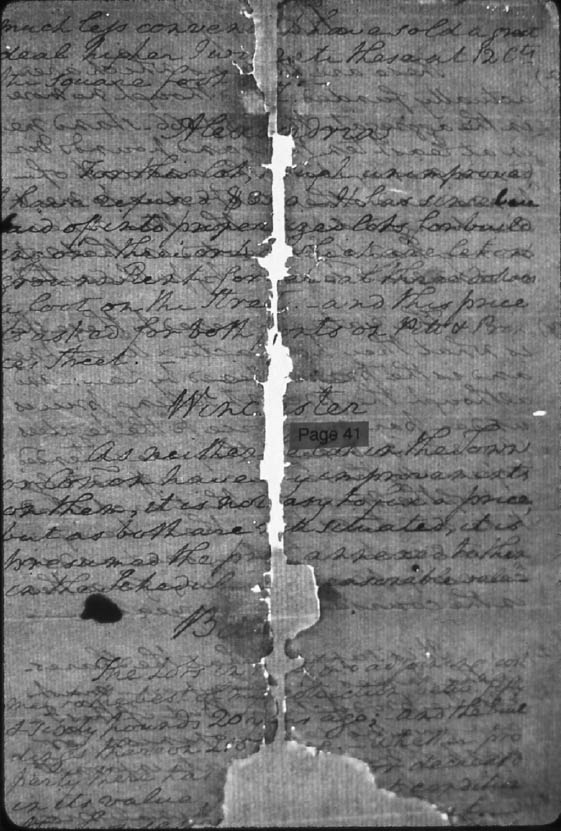

ABSTRACT—If an object that is in need of treatment already has evident repairs or restorations, questions arise about whether to reverse or preserve them. For example, are the prior repairs unstable? Are they causing damage to the object? Do they excessively impair a visual appreciation of the object? Other issues should also be considered, such as whether the repairs are appropriate to the culture of the object's origin, whether they may have spiritual or historical significance, and whether it is possible to know the artist's opinion about the repairs. Electronic media artworks present unique re-treatment concerns. Such issues need to be discussed with the owner whenever new treatment is planned. The author presents the reasons that some prior interventions have been preserved (or not) on a variety of cultural objects and offers a checklist of talking points to guide future discussions. TITRE—R�parations anciennes: quand doit-on les pr�server? R�SUM�—Lorsqu'un objet n�cessite un traitement et qu'il poss�de d�j� des traces �videntes de r�parations ou de restaurations anciennes, on se questionne aussit�t sur l'importance de les pr�server ou non. Par exemple, ces r�parations sont-elles instables? Occasionnent-elles des dommages � l'objet? Sont-elles visuellement g�nantes? D'autres consid�rations sont �galement importantes � savoir si ces r�parations sont appropri�es par rapport � l'origine culturelle de l'objet, si elles ont une signification spirituelle ou historique, et lorsqu'il y a lieu, si le cr�ateur de l'oeuvre objecte � leur pr�sence sur l'objet en question. Quant aux œuvres contemporaines qui int�grent des composantes �lectroniques, elles pr�sentent une probl�matique particuli�re. Au moment de planifier un nouveau traitement, il importe de discuter de ces diverses questions avec le propri�taire de l'oeuvre. Dans cet article, l'auteur pr�sente les raisons qui l'ont conduite � pr�server ou non des restaurations anciennes sur une vari�t� d'objets culturels. Elle fournit �galement une liste des points qui pourront guider d'�ventuelles discussions sur ce sujet. TITULO—Reparaciones previas: �cu�ndo deber�an ser preservadas? RESUMEN—Si un objeto que esta necesitando un tratamiento ya posee reparaciones o restauraciones evidentes, surge el interrogante de si estas debiesen ser removidas o preservadas. Por ejemplo, �Est�n inestables las reparaciones anteriores? �Est�n causando alg�n da�o al objeto? �Dificultan excesivamente la apreciaci�n visual del objeto? Otros problemas que tambi�n deber�an ser considerados, son los siguientes: si las reparaciones son apropiadas para la cultura original del objeto, si tiene alg�n significado espiritual o hist�rico, o si es posible saber la opini�n del artista al respecto. Las obras de arte hechas con medios electr�nicos presentan consideraciones �nicas al ser tratadas de nuevo. Tales problemas deben ser discutidos con los due�os siempre que se planee hacer un nuevo tratamiento. El autor presenta las razones por las cuales algunas intervenciones previas han sido preservadas (o no) en una variedad de objetos culturales y ofrece una lista de temas a plantear que podr�n servir como una gu�a para las conversaciones futuras.TITULO—Reparos anteriores: quando preserv�-los? RESUMO—Se um objeto, que necessita restauro, j� apresenta reparos ou restaura��es evidentes, surgem d�vidas sobre revert�-los ou preserv�-los. Por exemplo, os reparos anteriores s�o inst�veis? Est�o causando danos ao objeto? Eles comprometem excessivamente a leitura visual do objeto? Outros aspectos deveriam ser considerados, tais como: se os reparos s�o adequados �s origens culturais do objeto, se eles t�m significado espiritual ou hist�rico e se � poss�vel conhecer a opini�o do artista sobre os reparos. Obras de arte em m�dia eletr�nica representam uma preocupa��o sui generis no retratamento. Tais aspectos precisam ser discutidos com o propriet�rio sempre que um novo tratamento � planejado. O autor apresenta as raz�es pelas quais algumas interven��es anteriores t�m sido preservadas (ou n�o) em uma variedade de objetos culturais e fornece uma lista de assuntos para orientar futuras discuss�es. 1 INTRODUCTIONThe goal of conservation is to preserve art and artifacts. This article proposes that some repairs made to cultural objects in the past are worth preserving along with the objects themselves, and that it might be helpful to agree upon guidelines that would help owners and conservators to determine which prior treatments to preserve. 1.1 DEFINITION OF TERMSThe following terms will be used as defined here: Treatment: This term refers broadly to the application of any physical or chemical means intended to correct a perceived condition problem on a cultural object. Repair: A repair is the rejoining or reinforcement of components that have (for example) broken, torn, or delaminated. Materials added during repair may or may not be noticeable. Restoration: This term refers to the addition of one or more materials (including paint) to an object, to replace original components that are missing or damaged beyond repair. Substitution or migration: Both terms refer to the purposeful exchange of entire units of original material for new units. Migration in this context refers especially to components of electronic and digital artworks. 1.2 BACKGROUNDRarely does a conservator encounter an artifact that has not already received some form of treatment intended to correct an altered condition. Perhaps a darkened varnish has been removed from a painting, or a broken fragment has been reattached to a sculpture, or a torn document has been mended. Is any of those old interventions significant in its own right, and should it remain evident even after a new conservation treatment? The reasons for retaining old repairs vary, and they may not be obvious, but it is risky to ignore this aspect of preservation. Sometimes the evidence of an old intervention adds value. Reversing a prior repair usually results in yet another “permanent” change in the object's appearance. When a repair that has altered the appearance of an object for a time is reversed, the prior repair can be documented and the removed materials can be stored. However, these pieces of evidence can later become separated from their associated cultural objects. Historic connections may be lost. For these reasons, the decision to reverse a prior repair must be made thoughtfully, with full agreement between the owner and the conservator. If there is a chance that a prior repair enhances an object's intangible or monetary value, it is best to explore this matter before proceeding with conservation. 2 PAST PRACTICEA limited bibliographic search for relevant publications and a query posted to colleagues via the Internet yielded no general protocol for deciding when old repairs should be retained. Owners and the conservators they consult are frequently faced with making such decisions, and some have evolved protocols for how to deal consistently with recurring situations in their own collections. An example of this situation can be found in an article (Podany 1995) concerning the conservation of ancient marble sculptures owned by the Getty Museum. But evidently no one has proposed developing broad general guidelines for how to deal with prior repairs. Articles about the conservation of specific previously treated objects tend to stress the importance of two things: stability and aesthetics. Does the prior intervention make the object unstable? Is the appearance after repair aesthetically acceptable? If an old treatment has not caused new risk or damage to the object, and if it is pleasing to the eye, it will likely be retained. Sometimes a third factor is mentioned: economy. What is the additional cost to replace an old repair? The cost of re-treatment can be a reason not to reverse a stable repair, even when it looks less than perfect. This article explores other considerations besides those three. 3 REPAIRS THAT HAVE HISTORIC VALUESometimes repairs provide eloquent mute witness to the history of a damaged object. The circumstances that led to the repair, or the person who applied it, can be linked with notable historic moments. Even when the origin of an old repair is uncertain, it can attain the status of an essential attribute. In such cases, noticing the prior repair can enhance a viewer's enjoyment of the object. 3.1 GEORGE WASHINGTON'S WILLChristine Smith, president of Conservation of Art on Paper Inc., dedicated more than three years to conserving George Washington's last will and testament, completing her work in 2002. The 44-page will is owned by Fairfax County, Virginia, where it was filed shortly after Washington's death in 1788. During the Civil War, this historic document was folded, moved about, and even buried in a wine cellar. Its pages sustained various damages, including tears that were secured by sewing. Later, in 1910, the will received its first professional conservation treatment from William Berwick (1848–1920), manuscript restorer at the Library of Congress (Ginsberg 2000; Smith 2002). The recent treatment by Smith preserves many of the earlier repairs, such as the thread remnants of sewing mends that date from the Civil War and the fills of fine, well-matched laid paper that Berwick added to the larger losses. The stitching holes and thread remnants (fig. 1) are part of the document's history. They are evidence of the struggle to keep it safe in trying times. Berwick's fillings (fig. 2) are historic for another reason. They reveal that Berwick's work was at the threshold of modern paper conservation in the United States. But Smith reversed other repairs. Silk sheets that Berwick pasted over the front and back of each page to reinforce it eventually stiffened and darkened the sheets, prevented adequate repair of underlying areas, and obscured the writing, so all the silk was removed, as were scattered localized transparent-paper reinforcements that had discolored some pages and caused some to warp. Smith worked closely with the owner and other knowledgeable advisers when she planned the will's treatment. She had specific reasons for deciding which prior repairs to retain, stressing aesthetics and stability and also the desire to preserve the beautifully made fillings that Berwick applied almost a century ago and that have remained in excellent condition. But to this author she spoke of wishing that there were a less subjective way to make such decisions (Smith 2002). 3.2 HOPI KACHINAAn old repair, especially one that may have been made by or for the object's original owners, can gradually become an accepted attribute. The Brooklyn Museum owns a collection of Hopi kachina dolls that were acquired in 1904 by curator Stewart Culin for the museum's new department of ethnology. Culin purchased the lot from Wetzler Brothers, a store in Holbrook, Arizona. Among them (fig. 3) is a kachina that represents Kokopol (an erotic personage sometimes called Kokopelli) that has an obvious break through its right arm. The forearm is secured with a hide thong inserted through horizontal holes on either side of the break and knotted on the inner side of the elbow. The museum's archivist, Deborah Wythe (2002), found no specific reference to the repair in the museum's earliest records of this figure, which are in the 1904 Stewart Culin Expedition Records. A later (undated) departmental catalog card notes the existence of a thong repair. Eventually, as notes were added to the records of this object in the 1980s by research associate Ira Jacknis, they started to refer to a “possible native repair“ (Wythe 2002). Museum conservator Lisa Bruno shared with the author the latest conservation records of this kachina, which include a 1991 treatment report (filed in the Conservation Department, Brooklyn Museum of Art) by conservator Tina Krumrine. Krumrine here notes two prior repairs of breaks through the figure's right arm. She refers to the old visible repair with a thong as a “native repair,” in contrast to another break repair near it, which had been rejoined inconspicuously using a synthetic resin emulsion (fig. 4). Neither break was re-repaired in 1991 when the kachina received

4 REPAIRS THAT HAVE CULTURAL OR SPIRITUAL VALUEDecisions about whether to retain or reverse existing treatments on objects from other cultures are commonly based on the opinions of the present caretakers about the appropriateness of the repairs. Increasingly, owners and conservators are seeking the advice of a responsible member of the originating culture or of a scholar who has studied that culture.

4.1 ZUNI WOODEN WAR GODSIn many cultures there are certain objects that are considered sacred, that is, they serve a religious purpose. One of the earliest American conservation articles to stress the importance of this intangible component of such artifacts states that “we should reconsider the circumstances under which sacred objects undergo modern, scientific conservation treatment, since the very process of handling, documentation and treatment could constitute interference with the integrity of the object and destruction of its functional and spiritual value” (Wolfe and Mibach 1983, 1). The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990 forced owners and conservators to accept that in some cases even simply storing a sacred object indoors might not be acceptable. The year after NAGPRA went into effect, a journalist reported that a group of 13 ancient Zuni wooden war gods being repatriated from the Brooklyn Museum to the Zuni tribe in New Mexico would be placed outdoors and permitted to deteriorate naturally according to tribal custom (Miller 1991). One could interpret this move as an intentional reversal of the previous treatment (preventive care by protection from weathering) based on spiritual exigencies of the originating culture.

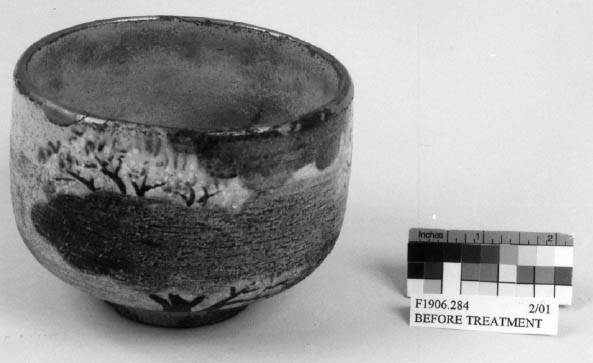

4.2 TWO JAPANESE TEA BOWLSTwo Japanese Kenzan-style tea bowls owned by the Smithsonian Institution's Freer Gallery of Art have old repairs. In preparing these 19th-century

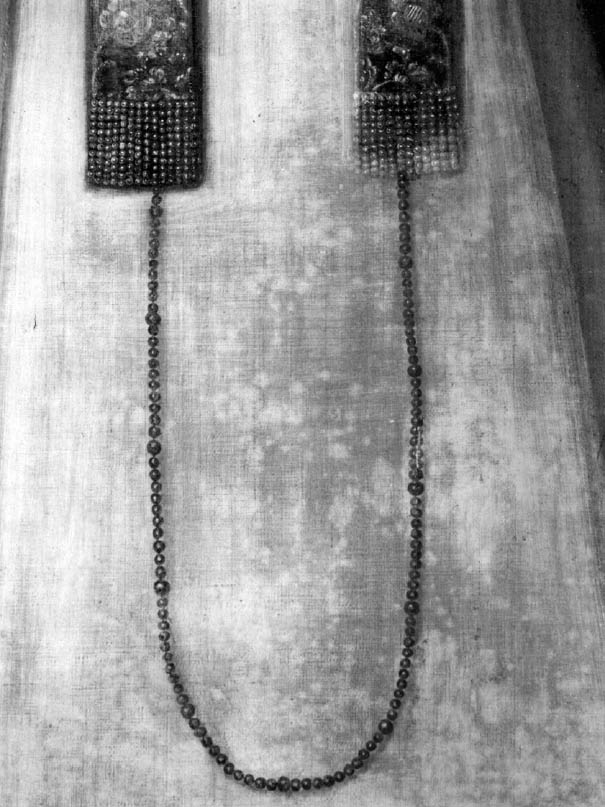

The entire rim of tea bowl no. F1906.284 (fig. 5) had been repaired with red lacquer coated with gold. These old repair materials now have fine cracks, and a few areas of the lacquer have begun to lift away from the ceramic. Because the prior repair was deemed culturally appropriate in both style and materials, the new treatment was limited to stabilizing it by applying a synthetic resin to areas of the lacquer that were cracked or lifting. The old repair of tea bowl no. F1911.509 (fig. 6) was very different. Small chips and large mended breaks in the broken bowl had been painted with an excess of a silver-colored metallic paint that was soluble in organic solvents. In both style and material, this crudely applied repair was at odds with the Asian traditions of ceramic restoration. Therefore the decision was made to re-repair the bowl using modern techniques and materials. 4.3 KIOWA BEADED CRADLEThe Kiowa and Comanche peoples made elaborately decorated cradles for their babies during the reservation period (1860s–ca. 1920). According to Barbara A. Hail, deputy director and curator (now curator emerita) of Brown University's Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, this type of cradle was culturally significant as a marker of earlier times before these peoples were defeated by the U.S. Army and began to lose their cultural identity (Hail 2000, 2002). A particularly fine example is the Kiowa lattice cradle that a woman named Hoygyohodle (1854–1938) decorated for the baby of one of her relatives (fig. 7). This well-documented cradle is constructed of two boards 119 cm long joined in a narrow V shape to support a deerskin and rawhide form for holding the baby. The outside of this form is entirely covered with colored-glass seed beads sewn on in an abstract pattern.

The beading on the Hoygyohodle cradle had been restored more than once, and more beads needed to be replaced before an exhibition that traveled from December 1999 to January 2002. According to Hail (2002), Alexandra Allardt O'Donnell, the Haffenreffer Museum's consultant conservator, contributed to the cradle's conservation by doing some stabilizing work and adding some stuffing, but she neither removed nor added any beads. Rebeading (to fill losses) was done by Vanessa Paukeigope Jennings, a Kiowa cradle maker who was brought to the museum to do this work under O'Donnell's supervision (fig. 8).

O'Donnell explained (2002): “We kept the old beading repairs as they represented a continuum of

5 TREATMENTS PERFORMED BY OR FOR ARTISTSArtists sometimes repair their artworks while they still own them or when they are invited to do so by subsequent owners. Sometimes artists also treat the creations produced by other artists. When an object that needs conservation has been previously repaired by a professional artist, it is prudent to investigate the circumstances thoroughly before proceeding.

5.1 ANDREAS LOPEZ'S PAINTING SOR PUDENCIANAOlana, located near Hudson, N.Y., is the former home of the artist Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900) and is now a New York State Historic Site. On exhibition at Olana are paintings by Church and other paintings that he collected. Among the

When the painting was surveyed at Olana in 1989, Zucker and Olana's site manager and curator jointly arrived at the decision to leave the painting looking much as it must have after Church's treatment. According to Zucker (2002), all three felt that, in the context of its present setting, it was more important to preserve the portrait's appearance as Church had altered it than to inpaint the losses.

An article that describes how Church purchased and then cleaned the painting was found by Gerald L. Carr, an independent art historian, when he was doing research for his Catalogue Raisonn� of Works of Art at Olana State Historic Site (University of Cambridge Press, 1994). This article appeared on the front page of the March 16, 1895, issue of Two Republics, an English-language periodical that was published in Mexico City from 1867 to 1900. Zucker provided me with a photocopy of the microfilmed periodical, which is difficult to read because of bleed-though ink staining.1 (The last two letters of the

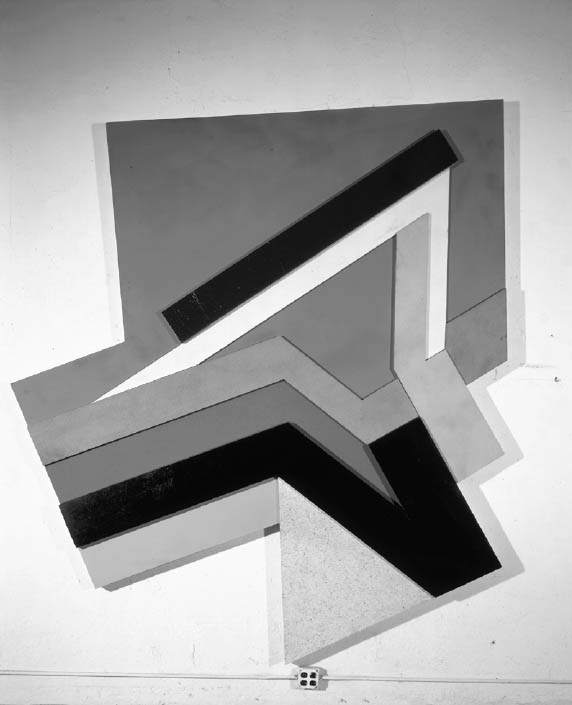

One of the great delights of Mr. Frederick [sic] E. Church, the celebrated landscape artist, when he is in Mexico, is to snoop around the bric-a-brac stores seeking what he may purchase. Sometimes it may be a bit of jade centuries older than the conquest, a proof, may be, of commerce with South-eastern Asia, a statuette of the Virgin by Tresguerras, sometimes a good bit of pottery, occasionally a book with rare engravings. For the first time a week or two ago, he purchased a picture, which though grimy with dirt and discolored varnish revealed to his artistic eye certain qualities which only a good painter could possess. It was a portrait of a young lady in the costume of a novice, and there was a long statement at the bottom, which required to be cleaned before it could be deciphered. The great artist has a passion for mending and repairing things, and he was convinced that if this picture were relieved of its dirt and varnish, it would be of such merit as to make it worth his while to patch up its numerous tears and make it ready for framing. To clean it, he used an invention of his own, a mixture of alcohol and castor oil, which when combined form a gummy grease of the most efficaceous character, innocuous to paints generally, with the exception of one or two earths which disappear with the dirt. For several days he was invisible, and when his friends were admitted they saw the result of his labors, though the picture still remains under the disadvantage of not having been revarnished. It is a life size portrait of Sister Pudencia [sic] Josefa Manuela del Corazon de Maria, … who was born May 19th, 1757, and took the vow of a Nun of the Convent of the Incarnation of this court of Mexico August the 15th, 1781, and made her solemn profession … Sunday August 25th, 1782. Andreas Lopez was the painter according to the signature which the cleaning revealed, and the writer remembered to have seen the name in a list of painters whose works existed in the city of Puebla. The existence of this contemporaneous account influenced the choice not to inpaint losses sustained during the old cleaning of the portrait of Sor Pudenciana. Because the painting hangs in Church's home, and because he was the painting's collector and restorer, the team at Olana considered it more important to preserve the visual evidence of Church's involvement than to preserve the intent of the artist who created the painting. 5.2 FRANK STELLAThe decision to preserve or replace a prior repair must take into consideration the opinion of the artist whenever it is possible to know this. The opinion of the artist is especially important when the artist is living, because he or she may provide important technical information about the object's materials or construction. There is also a legal reason to seek the artist's views: federal law and some state laws protect an artist's right to control the appearance of his or her artwork. The artist Frank Stella, in a telephone conversation with the author on March 7, 2002, said that for many years he avoided the subject of restoration, and now he believes that it might have been better to discuss it openly. For example, he explained that sometimes an owner of one of his pieces tries to persuade him to repair it. “They think it's worth more if the artist fixes it. That's not true. … It's dangerous!” Asked whether he had ever repaired his own work, Stella laughed and said, “I've done it about twice, and I've just ruined it. Fortunately, I worked on pieces that I owned.” He mentioned also that he has made creative changes while restoring one of his artworks from an earlier period. Would Stella want his repair to remain, if an object that he had restored required more restoration later? His response was to emphasize what is most important to him. Referring to a series that he made using felt covers (Polish Village Series, 1970–73, fig. 11), the artist remarked that when the original felt

5.3 GABRIEL OROZCO'S SCULPTURE RECAPTURED NATUREWhen artists work with untraditional materials, conservators may be forced to seek untraditional methods of art preservation. If the artist is living and wishes to cooperate with the preservation of a fragile artwork, the best result may come from a collaboration among the artist (possibly also his or her fabricator), the sculpture's owner (or authorized agent), and the conservator. A case in point is how to preserve Gabriel Orozco's Recaptured Nature (fig. 12). This is an abstract inflated form made of inner tubes of truck tires fused together with vulcanized natural rubber. The object was fabricated for the artist in Mexico City in 1990 in a shop near the artist's studio. When the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA) acquired the sculpture in 1997, the artist had already given specific instructions for repairing leaks in the seams: repairs can be made as long as the patches are oval and made from black rubber. According to Michelle Barger, SFMoMA's associate conservator of objects, the vulcanized rubber that was used to make the original seams has embrittled faster than has the rubber of the inner tube tires. Although the sculpture has been patched by previous owners, new holes continue to develop in the seams (fig. 13). Before this sculpture can again be inflated and exhibited, it will have to be re-treated. Barger explained the museum's point of view:

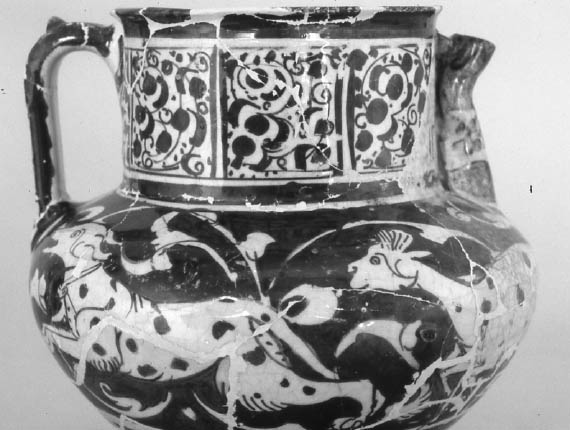

6 RE-TREATMENTS THAT ARE TECHNICALLY CONFUSINGWhen an object has been treated more than once, sometimes the repairs applied at different times are difficult to distinguish. Technical analysis of each applied material may be required in order to determine whether it is appropriate—or even possible—to remove any of them. (In the case of works created with modern electronic media, when documentation is lacking it may be impossible ever to distinguish imposed alterations. See sec. 7, below.) 6.1 AN ISLAMIC EWERSometimes an old restoration is so skillful that it clouds an understanding of the object's true condition, which only becomes apparent upon re-treatment. Conservator Stephen P. Koob discovered this effect while working on a Seljuk luster-glazed ceramic ewer of the late 12th century or early 13th

Koob states in his article about this repair that he and the curator decided to reuse the restoration fragments from the old repair in his re-treatment of the ewer, primarily because “the replacement fragments are well-fired, stable and an excellent match to the original,” but also because reusing them was economical (Koob 1999, 163). There is a third reason to retain these beautifully manufactured fills: they exemplify excellence in ceramic restoration—or deceit!—in a past era. Hence a “joint curatorial/conservation label has been proposed to present the viewer with an understanding of the original and the restoration” (Koob 1999, 164). 6.2 THE CARLOS MUSEUM'S EGYPTIAN COFFINSAncient Egyptian artifacts are among the oldest cultural objects that conservators work on, and they may have repairs that date from widely disparate eras. It is useful to read descriptions of treatment materials and techniques applied in the past that have been observed by modern conservators (Jaeschke and Jaeschke 1988; Norman 1988).

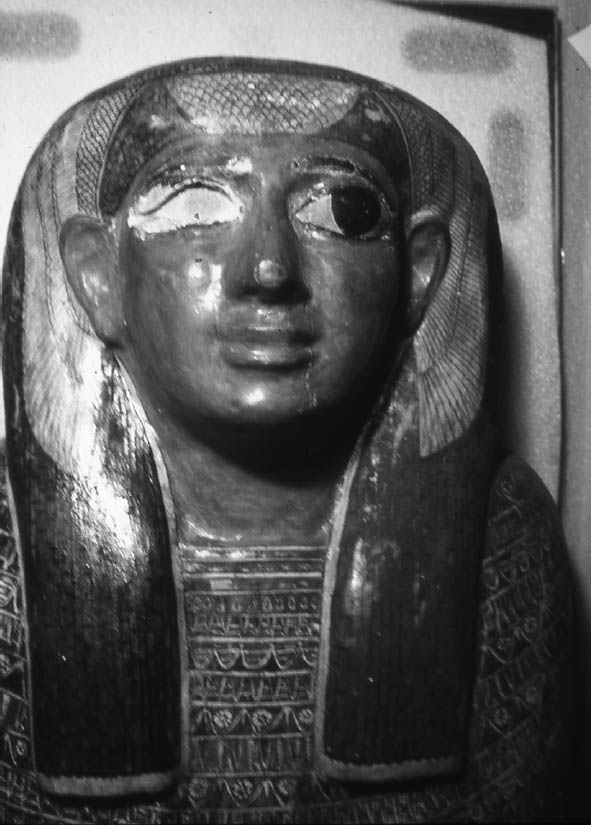

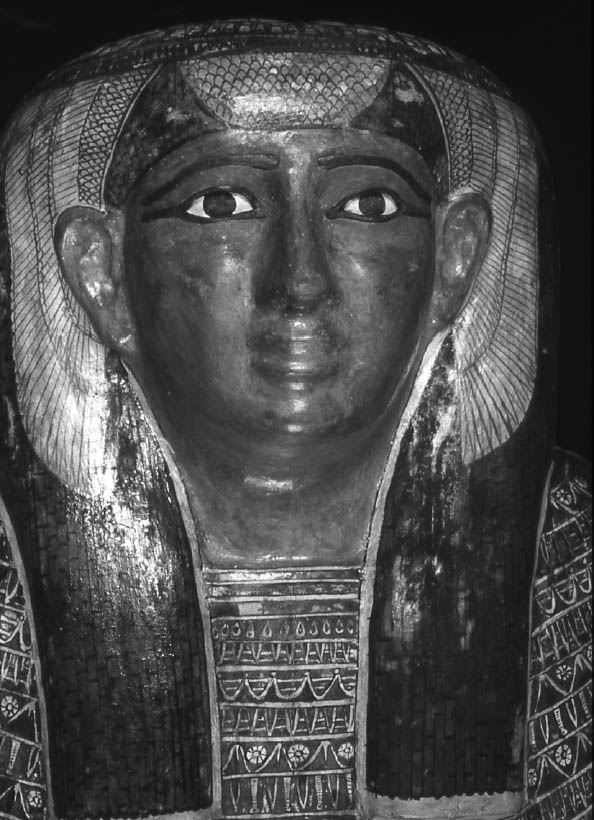

If components of coffins were reused later, or old repairs were modified with newer materials, it becomes difficult to distinguish among the various interventions. Conservators and curators at the Michael C. Carlos Museum of Emory University have been working on a multiyear cooperative effort to conserve some Egyptian coffins (Stein et al. 2002). These coffins had received many modern repairs and restorations during the approximately 150 years that they were part of another collection before the Carlos Museum acquired them in 1999. Structures had been reinforced, losses (both structural and superficial) filled, and restorations added. The coffins had also suffered fire and water damage. As the examination and treatment at the Carlos Museum advanced, traces of ancient damages and repairs also became evident. On a set of two nesting coffins that were built and decorated in the 25th dynasty 760–656 B.C. for the female mummy of Iawttavesheret, modern large yellow eyes made of plaster had been affixed to the

The Carlos Museum team also found evidence of what they believe are ancient repairs and alterations due to reuse of a coffin for the funeral of another person. The lid of a coffin originally made in the 21st dynasty 1075–945 B.C. for a woman named Tanakhtanettahat appears to have been reused in antiquity (accession no. 1999.1.17C). A cracked area across the lower legs seems to have broken and been repaired before the coffin was reused for another mummy. This ancient repair has now been documented and preserved. During this process it was also decided to remove (and save) isolated areas of the extensive ancient overpaint, so that viewers could see that beneath it there is still well-preserved, delicately painted original decoration (Stein et al. 2002).

Work on these coffins has been technically complex. For example, conservator Ren�e Stein explained (2002) that it has not been possible to fully According to Stein, it may be impossible to selectively reverse some kinds of prior treatments. Even if a modern oil were identified on one of the coffins, it would be difficult to remove if the coating had penetrated a porous or chemically similar original layer beneath (Stein 2002). In such cases, the author of this article believes that maybe the best one can do is use the clues provided by analyzed samples to create modified digital photographs suggesting how such artifacts might have looked after the ancient treatment and before modern interventions. 7 RE-TREATMENTS IN A NEW LIGHT: ELECTRONIC AND DIGITAL ARTDuring the second half of the past century, some artists began creating works in electronic media. Conservators are now sharing concerns with librarians and archivists about how to preserve works made in these new formats, the technology of which continues to change rapidly. Discussions about the preservation of such artworks almost always focus on the predicted obsolescence of their components, including the recorded visual and audio elements and the hardware that allows them to produce their intended effects. Replacements for damaged components are also likely to become unavailable. Artists and collectors of electronic artworks have learned to start preparing for their inevitable treatment and re-treatment when they create or acquire them (Vitale 2001). Ethical considerations (Brooks 1998) and general guidelines (Real 2001) for the care of such works have begun to be formulated. To reduce the burden of dealing with cycles of equipment obsolescence and the need to reformat (perhaps more than once) entire collections, it has been proposed that for video imagery a “preservation format must be universally recognized, promoted and adopted” (Messier 1998, 35). Walter Henry's PowerPoint slide series for a course called “Digital Preservation for 121L” is available at Conservation OnLine (Henry 2000). One slide of this series is titled “What Makes Digital Preservation Different?” and it lists two characteristics: a work created in a digital medium will undergo “no benign neglect” (because that is impossible for such materials), yet it “requires perpetual maintenance.” Henry was asked if he thought that concerns about re-treatments might also apply to digital materials. “Sort of,” he replied. “Normally when you work with digital materials, you produce a new ‘object’ and the original object can exist side by side with it.” But it does not always happen this way. Henry said, “If someone does some image enhancement to a digital image, the ‘restorer’ might actually overwrite the original or might save a new copy of the enhanced version, creating two versions of the ‘same’ object. In a perfect world, this would be perfectly documented and both versions would be retained” (Henry 2002). Regarding retreatment, Henry (2002) added, “If someone were to do an [additional] ‘enhancement’ they would normally work not from a previously enhanced version, but from the original master (after which there would now be three versions of the object).” One of the difficulties, he explained, is “the ease with which a digital thing can be presented as something it is not.” For instance, a viewer would have no way of knowing whether someone had changed the bits at a specific Internet address, or URL. Conservator Michelle Barger at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art said in March 2002 that SFMoMA has owned works created in electronic formats for over two decades. As a part of the accession process for electronic media, attempts are made to understand the artists' intent in their work and to understand the essential elements in terms of what can and cannot be modified. In order for such Substituting damaged original television screens and other physical components with comparable but different ones causes an obvious visual change. Much more subtle changes, such as shifts in color, are caused when migrating a work from videotape (in which the image gradually degrades) to digital format (in which the image quality remains the same). Video artist Nam June Paik, during a 1995 interview in Germany, made these remarks about what happens when the work of early video artists is transformed into modern systems in order to make them last:

Some works will remain exhibitable only as long as their owners continue to allow them to be migrated. Thus re-treatments—as one might classify repeated migrations—are crucial for preserving electronic and digital art. So is documentation, for without a record of what has been done, one cannot be sure that a decades-old work of art shown today accurately reflects the artist's intent. With conceptual art, however, whether or not it is electronic, the notion of preservation may be irrelevant. This is because each time that a conceptual artwork is exhibited (for example, a wall drawing by Sol Lewitt), it is created anew according to the artist's directives. In theory, at least, owners and conservators will never have to worry about which prior treatments to retain with this category of art. 8 CONCLUSIONSDeciding to reverse a previous treatment is a step that warrants careful thought. The earlier intervention may add to the object's value in ways that are not immediately apparent. Therefore, on those occasions when doubts persist about whether to remove evidence of a prior repair, it may be best to postpone this action. Current thoughts about the pros and cons for removal can be documented, and the repairs can be stabilized (if necessary) and left in place for another generation to inspect. With cultural objects that are expected to last many decades, there should be no rush to intervene aggressively without clear justification. Owners and conservators might find it useful to refer to a list of possible concerns when discussing the re-treatment of a previously repaired object. Here are some suggested talking points:

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSMany people assisted me during the preparation of this article, which was essentially a collaborative effort. I am especially grateful to the conservators and other people who are named in the text and who generously shared their views and pertinent records and helped me to state these cases clearly. (Opinions not specifically attributed to anyone else are mine, as are any errors in this article.) My thanks go also to the following individuals, whose responses to my initial queries were very helpful: Andrew Hare, Suzanne Hargrove, Helena and Richard Jaeschke, Paul Jett, Caroline Keck, Richard Kershner, Paula Pelosi, and Susan Zeller. I am grateful to Paul Whitmore and an anonymous peer reviewer for their excellent editorial guidance. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the dedication of the AIC Object Specialty Group Publications Committee, whose members proposed and planned this issue of the journal. NOTES1. The newspaper article that describes Frederic E. Church's purchase and treatment of a painting that now hangs at Olana is so pertinent, and so interesting, that my frustration at being unable to read crucial phrases led me to seek another photocopy. (Joyce Martindale, Texas Christian University's librarian, kindly provided one.) Thus, I discovered that this article may survive only as microfilm copies in a few scattered libraries and that all the copies may derive from the same imperfect master film. The thought of losing access to published writings of this kind prompts me to add this note—a plea for the preservation of old periodicals. REFERENCESBarger, M.2002. Personal communication. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Brooks, C.1998. Videotape preservation: Ethical considerations. In Playback: A primer for video, ed. S. J.Fifer, T.Gould, L.Hones, D. H.Norris, P.Ramey, and K.Weiner. San Francisco: Bay Area Video Coalition. Ginsberg, S.2000. Washington's final wishes: Restoring pages of first president's will “humbling” for Va. woman. Washington Post, December 14, B1, B4. Hail, B. A., ed.2000. Gifts of pride and love: Kiowa and Comanche cradles. Bristol, R. I.: Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, Brown University. Hail, B. A.2002. Personal communication. Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology, Brown University. Henry, W.2000. Digital preservation: A conservator's perspective. Paper presented at the Second Annual Stanford-California State Library Institute on 21st Century Librarianship, available at http://cpc.stanford.edu/ppt/henry-digpres (accessed February 26, 2002). Henry, W.2002. Personal communication. Preservation Department, Stanford University Libraries. Herzogenrath, W., B.Otterbeck, and C.Scheidermann. 1997. Nam June Paik: An interview with the artist. Wie haltbar ist Videokunst? How durable is video art? Proceedings of a symposium at the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, November 25, 1995, ed. B.Otterbeck and C.Scheidemann. Wolfsburg, Germany: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg. 103–7.

Jaeschke, R., and H.Jaeschke. 1988. Early conservation techniques in the Petrie Museum. In Conservation of ancient Egyptian materials, ed. S. C.Watkins and C. E.Brown. London: Institute of Archaeology Publications, United Kingdom Institute for Conservation Archaeology Section. 17–23. Koob, S. P.1999. Restoration skill or deceit: Manufactured replacement fragments on a Seljuk lusterglazed ewer. In The conservation of glass and ceramics, ed. N. H.Tennent. London: James & James. 156–66. Messier, P.1998. Criteria for assessing digital video as a preservation medium. In Playback: A primer for video, ed. S. J.Fifer, T.Gould, L.Hones, D. H.Norris, P.Ramey, and K.Weiner. San Francisco: Bay Area Video Coalition. Miller, T. L.1991. Museum to return Zuni statues. Downtown News (now The Brooklyn Paper), Brooklyn, N. Y, 14(15): April 12–18. Norman, M.1988. Early conservation techniques and the Ashmolean Museum. In Conservation of ancient Egyptian materials, ed. S. C.Watkins and C. E.Brown. London: United Kingdom Institute for Conservation Archaeology Section. 7–16. O'Donnell, A. A.2002. Personal communication. ArtCare Resources, Newport, Rhode Island. Podany, J.1995. Flaked, flayed or fractured? Development of loss compensation approaches for antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum. Loss Compensation: Technical and Philosophical Issues. AIC Objects Specialty Group postprints 2. Proceedings of the Objects Specialty Group Session, American Institute for Conservation 22nd Annual Meeting, Nashville, Tennessee, ed. E.Pearlstein and M.Marincola. Washington, D. C.: AIC. 38–56. Real, William A.2001. Toward guidelines for practice in the preservation and documentation of technology-based installation art. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation40:211–31. Smith, Christine. 2002. Personal communication. Conservation of Art on Paper Inc., Alexandria, Virginia. Stein, R.2002. Personal communication. Conservator, Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University. Stein, R., K.Singley, M.Leveque, A.Klingelhofer, and R.Harvey. 2002. Restorations revisited: Ancient and modern repairs encountered in the collection of an ancient Egyptian collection. AIC Objects Specialty Group postprints 8. Proceedings of the Objects Specialty Group Session, American Institute for Conservation 29th Annual Meeting, Dallas, Texas, ed. V.Greene and L.Bruno. Washington, D.C.: AIC. 2–14. Stella, F.2002. Personal communication. Vitale, T.2001. Techarchaeology: Works by James Coleman and Vito Acconci. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation40(3):233–58. Wolfe, S. J., and L.Mibach. 1983. Ethical considerations in the conservation of Native American sacred objects. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation23:1–6. Wythe, D.2002. Personal communication. Archivist, Brooklyn Museum of Art. Zucker, J.2002. Personal communication. New York State Bureau of Historic Sites, Office of Parks Recreation and Historic Preservation. FURTHER READINGFane, D., I.Jaknis, and L. M.Breen. 1991. Objects of Myth and Memory: American Indian Art at the Brooklyn Museum. Exhibition catalog. Brooklyn, N. Y.: Brooklyn Museum.

Native American Art Exhibit. 1992. Transcript of a discussion broadcast on March 4, 1992, on National Public Radio/Morning Edition, Brad Klein reporting. Washington, D.C.: National Public Radio. Accessed at http://www.npr.org. The repatriation of 13 Zuni war gods is mentioned. 379 AUTHOR INFORMATIONJEAN D. PORTELL is an independent conservator of sculptural objects. After receiving her bachelor of arts degree from Vassar College in 1962, she studied easel painting at the former Brooklyn Museum Art School. During this time she also worked as an office volunteer in the museum's Painting Conservation Laboratory, which was then headed by Caroline K. Keck. The museum hired her in December 1962 to assist Anton J. Konrad in creating a new conservation laboratory for the Department of Primitive Art and New World Cultures. During 1964–66, while living in Canada, she was hired by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts to equip and manage its first conservation laboratory and assist the museum's visiting consultant conservators. Returning to New York in 1966, she continued training in sculpture conservation with Konrad at his private studio in Brooklyn. In 1967, when the Museum of Modern Art hired Konrad to open its first sculpture conservation lab, she was hired to assist him. She worked part-time at MoMA (1967–69 and 1971–78) and also at Nelson Rocke-feller's Museum of Primitive Art (1968–70), where she assisted Jeanne Kostich. In 1978 she started a fulltime practice in sculpture conservation based in Brooklyn. For the past several years, she has also been researching the history of art conservation in the United States. Address: 13 Garden Place, Brooklyn, NY 11201.

Section Index Section Index |