THE EARLY PAINTED ENAMELS OF LIMOGES IN THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM: HISTORICAL CONTEXT AND OBSERVATIONS ON PAST TREATMENTS

TERRY DRAYMAN-WEISSER

1 INTRODUCTION

In his treatise Pirotechnia, the 16th-century master craftsman and metalworker Vannoccio Biringuccio said of enamel and glass: “Considering its brief and short life … it cannot and must not be given too much love, and it must be used and kept in mind as an example of the life of man and of the things of this world which, though beautiful, are transitory and frail” (quoted in Smith and Gnudi 1990, 132).

Many Renaissance enamels survive today in almost pristine condition. Biringuccio undoubtedly would be surprised but pleased to find that these enamels created in his lifetime are still being admired for their beauty 500 years later. However, some Renaissance enamels indeed tend to be “transitory and frail.” A group of these less durable enamels, the early painted enamels of Limoges, are now in the collections of the Walters Art Museum (fig. 1, see page 252). The technology, deterioration, and condition of these enamels are the focus of this study. Since attempts have been made to stabilize these actively deteriorating objects in the past, an evaluation of the success of these treatments will be presented.

Produced in Limoges in central France beginning around 1470, the early painted enamels are vividly colored pictorial images of religious subjects on rectangular copper plaques usually less than 27 cm in height. Often three plaques were created at once and grouped together in a frame to form a triptych. The original frames generally have been lost, and most of the enamels were remounted in the 19th and early 20th centuries in wood or fabric-covered wood and metal frames, probably to increase their salability for the art market. From the time the early painted Limoges enamels entered the Walters collection, they exhibited active deterioration phenomena such as crizzling, weeping, flaking, and salt efflorescence (figs. 2–4; see page 252 for fig. 3). The result has been loss of translucency, cracking, and pitting of the enamel surfaces. Similar deterioration has been noted in early painted Limoges enamels in other collections. 1 Thus the problems appear to be inherent in the enamels themselves, rather than related to poor handling or improper treatment. Philippe Verdier, who cataloged the Walters, Frick, and Taft Museum collections of painted enamels, commented, “Most of the enamels of the 1500s are partly eroded to the point of looking powdery or dusty” (Verdier 1957, 45).

Fig. 1.

Master of the Louis XII Triptych, Pieta with St. Catherine and St. Sebastian, current state. Late 15th century, enamel on copper, central panel 18.8 � 16.9 cm, wings 18.8 � 7.2 cm. Walters Art Museum 44.91

|

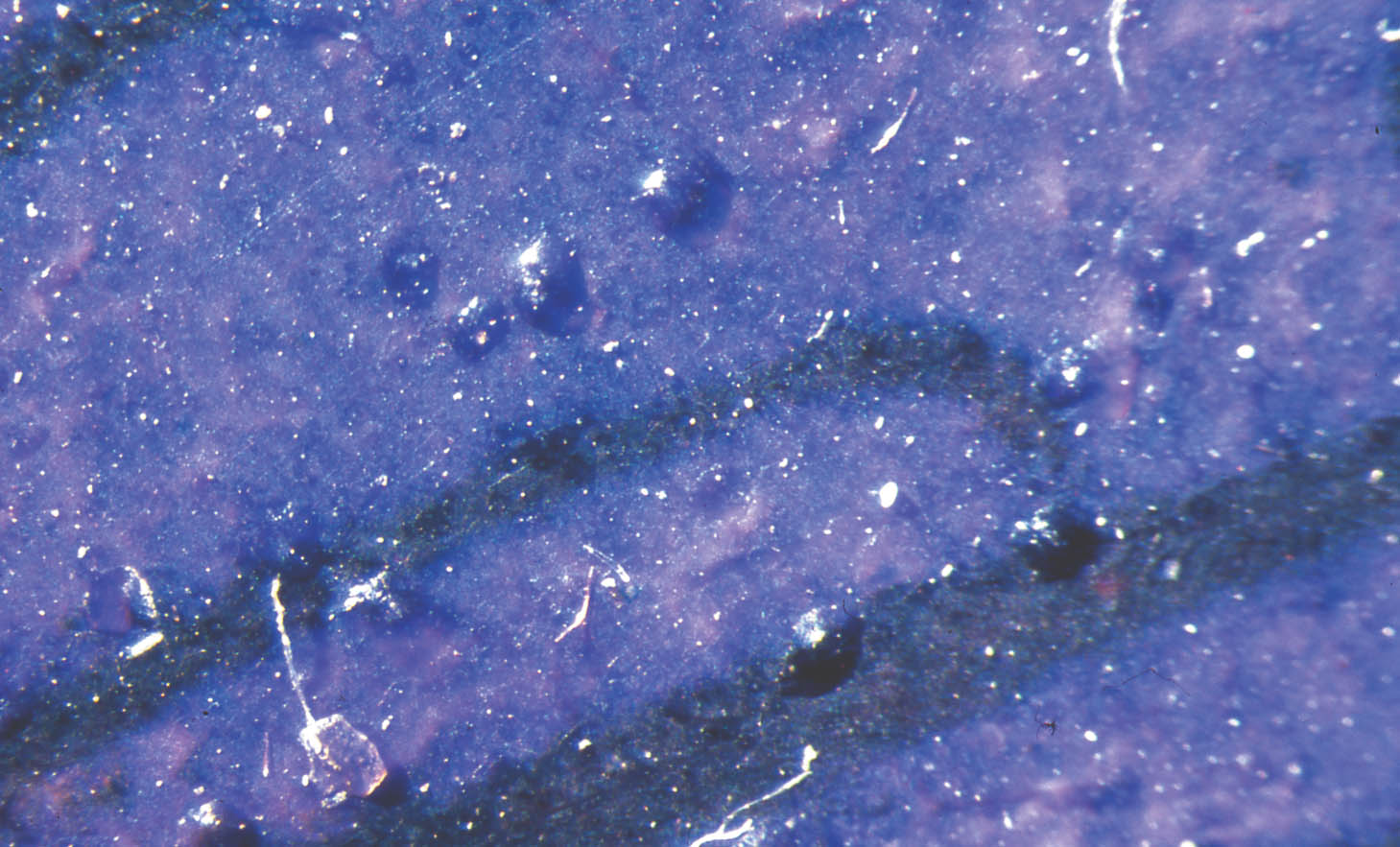

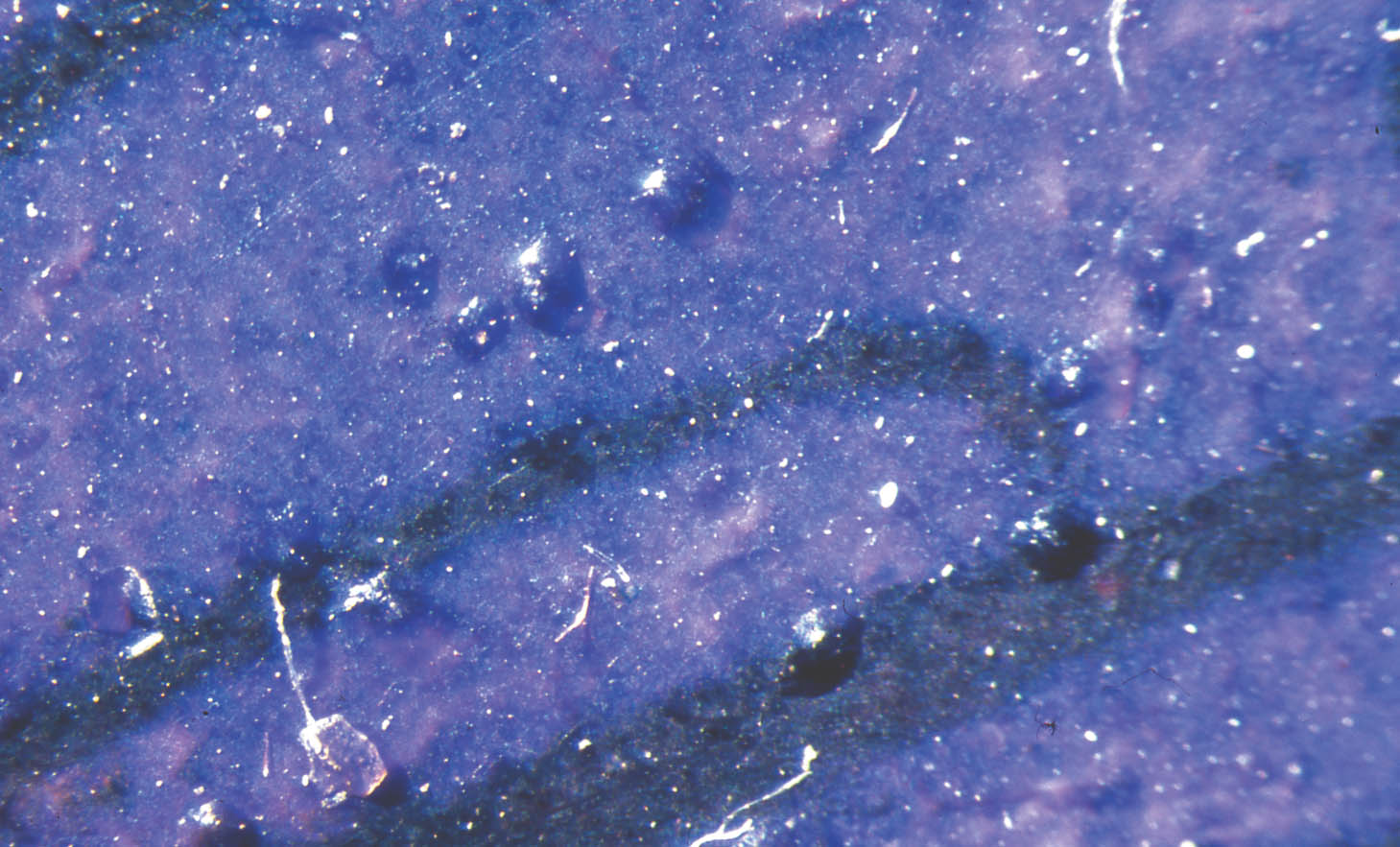

Fig. 2.

Detail, follower of Nardon P�nicaud, Man of Sorrows, showing crizzling in all areas except the white hand and sleeve decorations. Early 16th century enamel on copper, 21.3 � 17.1 cm. Walters Art Museum 44.438

|

The end of the early painted enamel period is generally accepted to be 1530, as several changes took place around that time. Strictly religious themes gave way to a mixture of religious and mythological themes, and the enamels from Limoges, no longer strictly devotional, became increasingly popular as luxury items. Vessels, plates, and other forms, in addition

Fig. 3.

Detail, Man of Sorrows (fig. 2), showing weeping on blue enamel

|

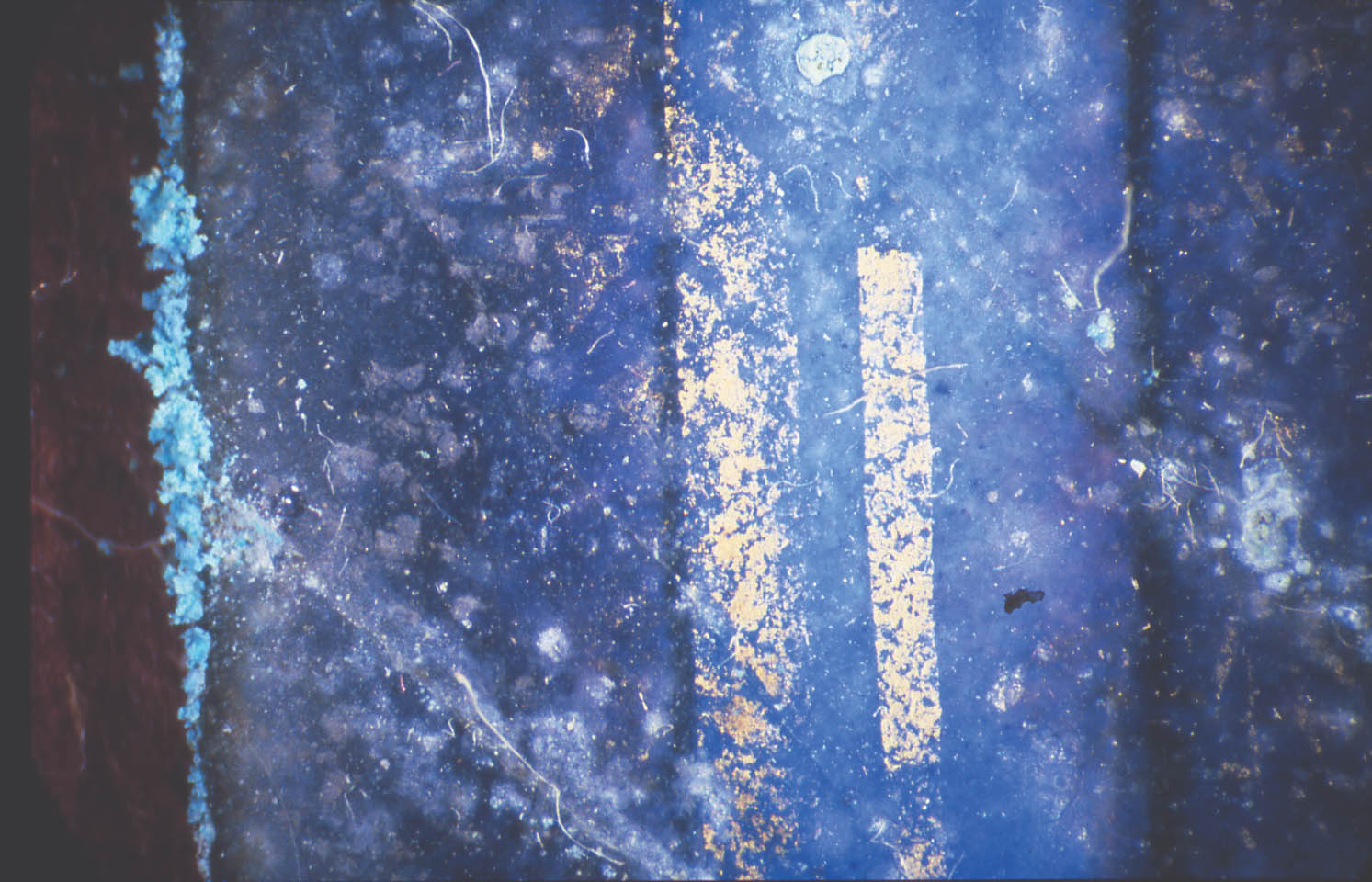

Fig. 4.

Detail, Nardon P�nicaud, Crucifixion, Bearing the Cross, Deposition, showing salt efflorescence that has disrupted the surface. Early 16th century, enamel on copper, center panel 27.3 � 23.5 cm, wings 27.3 � 10 cm. Walters Art Museum 44.149

|

to plaques, were decorated with painted enamel. The enamelers gained recognition as painters rather than craftsmen, often signing their work (Verdier et al. 1977). At the same time there were also changes in enameling techniques and compositions. It is not clear whether the changes in composition were in response to deterioration problems, new sources for raw materials to satisfy the increased demand for enamelwork, or some other influence. As a result of the changes in composition, the deterioration problems characteristic of the early painted enamels disappear, although a few later examples are known, such as an early-17th-century plaque in the Walters collection depicting the Crucifixion (fig. 5).

In the early 1960s Peter Michaels, a conservator at the Walters, developed and carried out a treatment on most of the unstable early painted Limoges enamels in the collection. The treatment generally involved washing the enamels with water followed by coating with a synthetic resin. This treatment restored the translucency of the enamels and appeared to stabilize them. Since that time, our understanding of the deterioration mechanisms in unstable glass and enamel has grown, and current conservation philosophy favors noninvasive treatment whenever possible. Therefore, from today's perspective, Michaels's treatments may seem intrusive, unusually risky, and perhaps more likely to accelerate than inhibit deterioration of the enamel. In an article on the deterioration of painted Limoges enamel plaques, Smith et al. questioned whether past treatments, including those by Michaels, will be effective over time (1987). After more than 40 years, it seems an appropriate time to evaluate the results of Michaels's treatments.

Fig. 5.

Detail, L�onard II Limosin, Crucifixion, current condition showing severe crizzling in the blue areas. Early 17th century, enamel on copper, 13.5 � 10.1 cm. Walters Art Museum 44.136

|

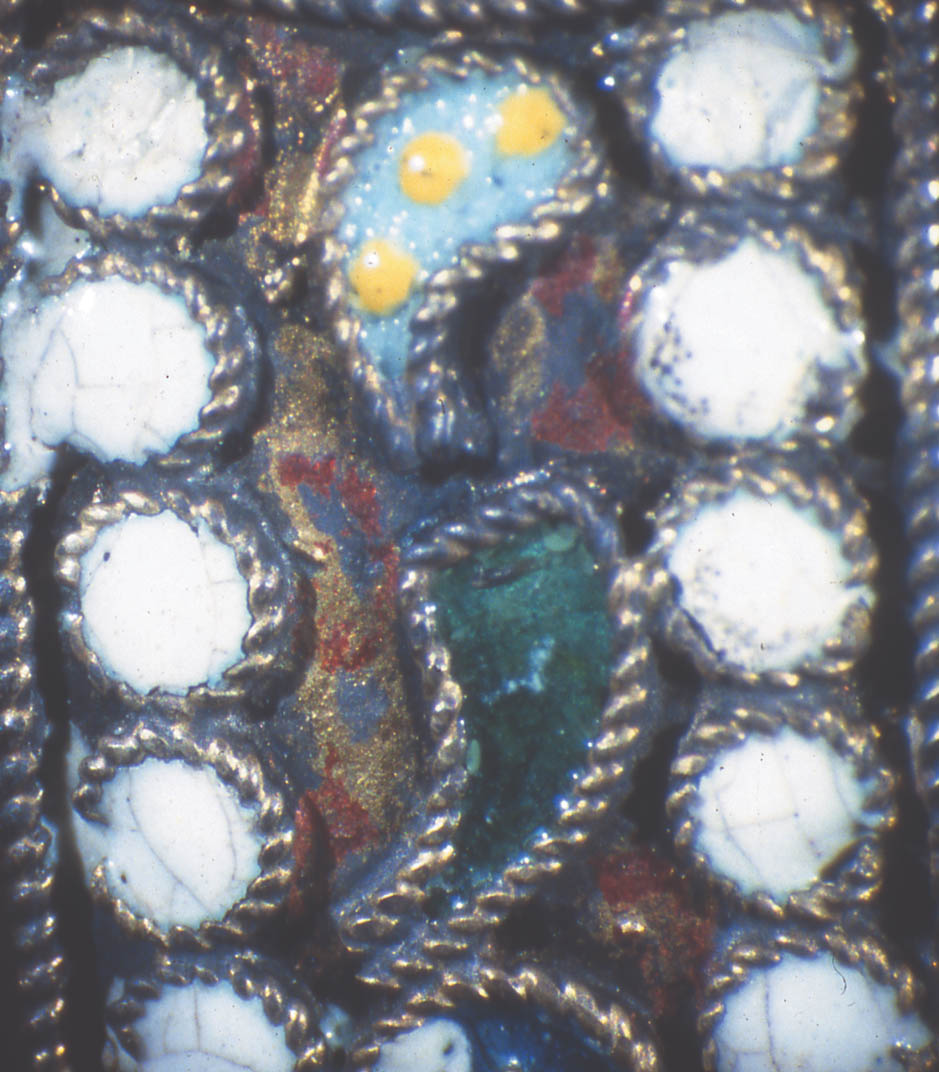

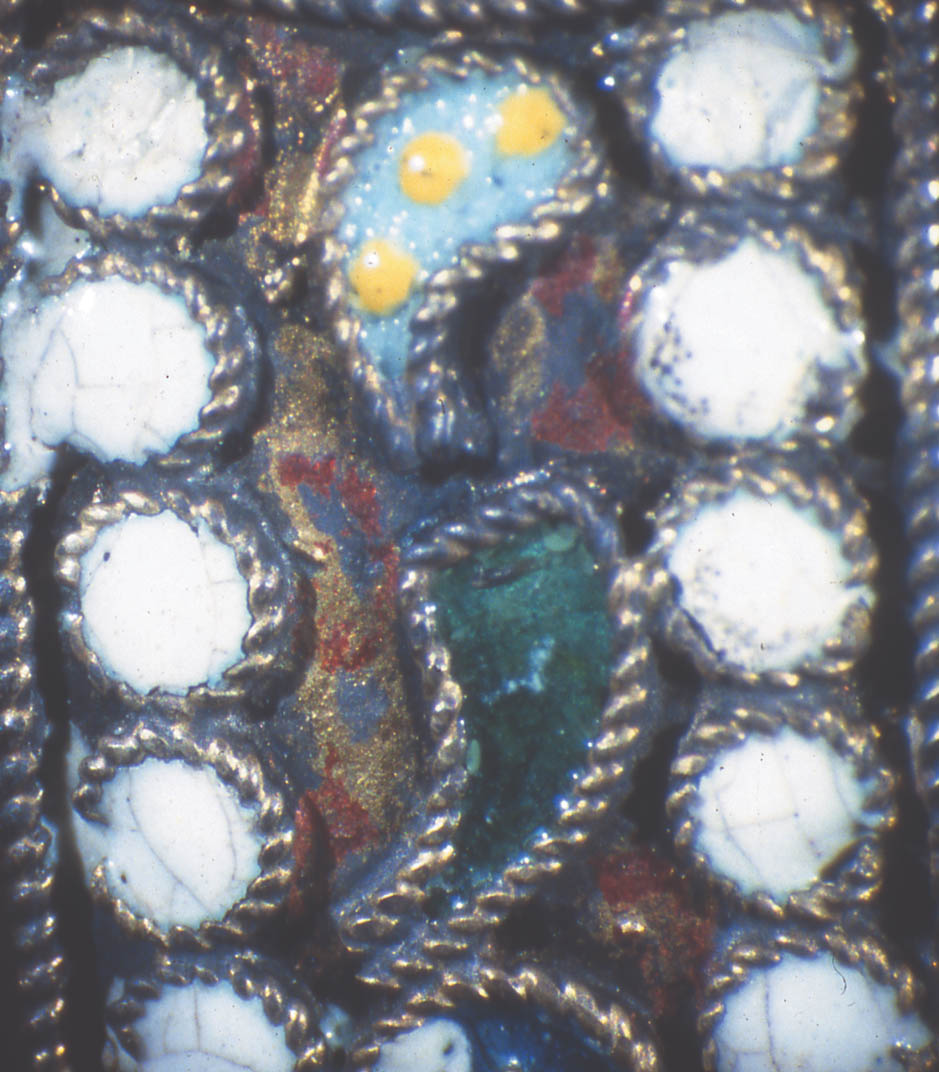

Fig. 6.

Detail, an example of filigree enamel. Russian, Moscow work, cup, 1660–90, coconut shell with enamel on gilded silver, height 11.5 cm. Walters Art Museum 44.194

|

Fig. 7.

Medallion with Christ, an example of cloisonn� enamel. Enamel on gold, diam. 3.9 cm. Walters Art Museum 44. 641. Although likely a Byzantine forgery, this example shows the technique especially in the damaged areas.

|

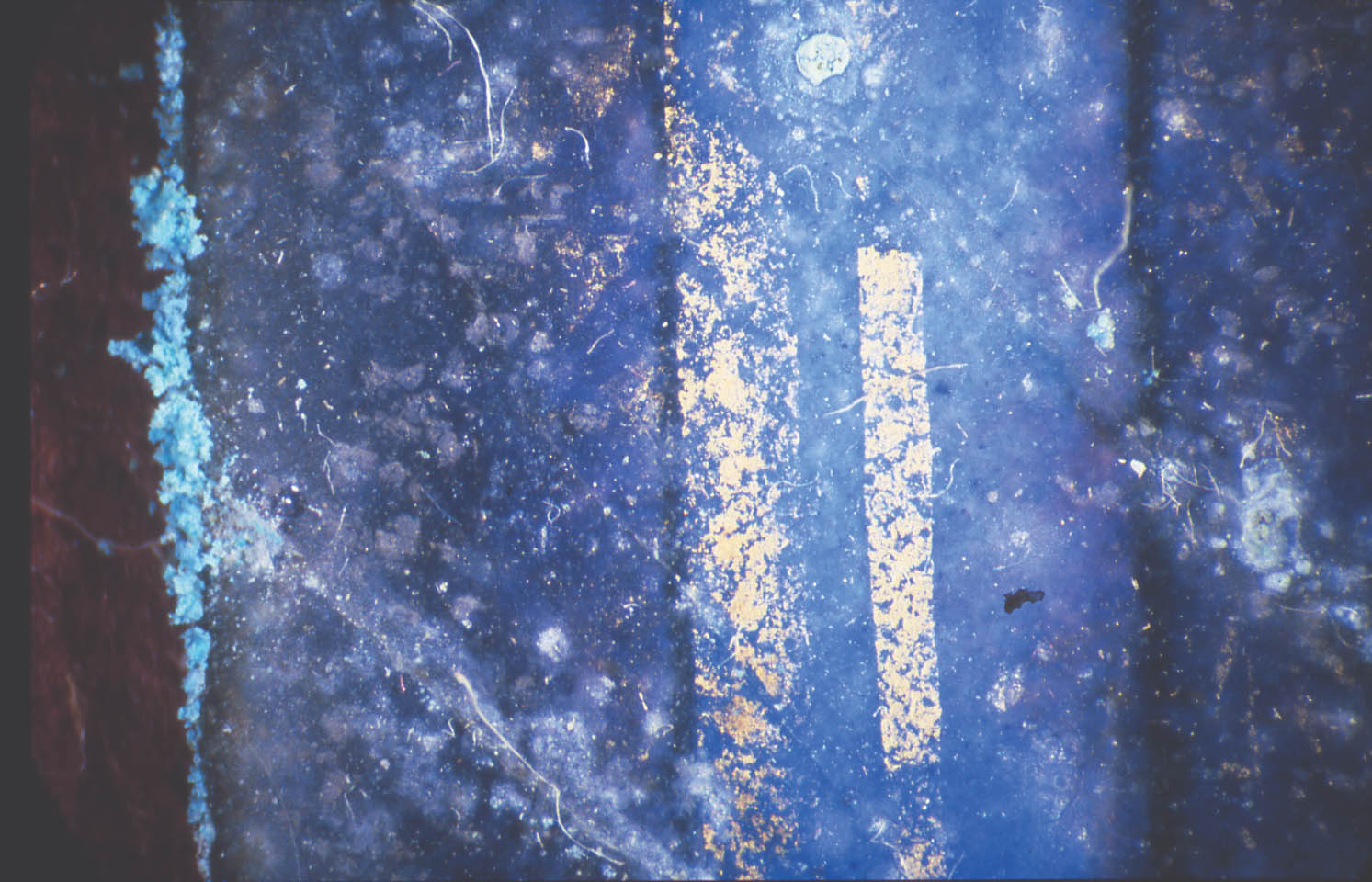

Fig. 8.

Detail, an example of plique-a-jour enamel. Russian, hanging lamp, 19th century, enamel and gilded silver, height 11 cm. Walters Art Museum 44.421.

|

Fig. 9.

Detail, an example of champlev� enamel. French, Limoges, pyx, 13th century, enamel on copper, 9.5 � 6.9 cm. Walters Art Museum 44.252

|

Fig. 10.

An example of basse taille enamel. French, pendant, ca. 1470, enamel on silver in gold case, diam. 3.8 cm. Walters Art Museum 44.590

|

Fig. 11.

An example of en ronde bosse or encrusted enamel. Spanish, pendant, 16th century, enamel on gold, 7.0 � 3.5 cm. Walters Art Museum 44.271

|

|