THE METHODS AND MATERIALS OF MARTIN JOHNSON HEADEELIZABETH LETO FULTON

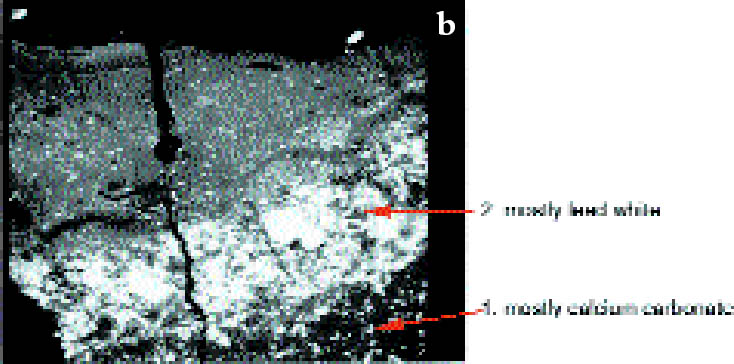

4 GROUNDSHeade must have been aware of the aesthetic importance of a bright ground in his paintings, as he exploited the effect of reflectance through thin paint layers, rendering brilliant colors in his paintings. The majority of the paintings in this study are painted on smooth, light-colored (off-white, tan, or gray) grounds that were commercially applied in two layers. This two-layer-type ground is probably the type referred to as the “most commonly encountered commercially prepared ground structure in 19th-century American paintings” (Zucker 1999, 6). Both layers contained a mixture of calcium carbonate and lead white, but the upper layer contained a higher percentage of lead white (fig. 2). The apparent reason for this mixture may have been economic: calcium carbonate mixed with lead white in the lower layers was cheaper than pure lead white, which was reserved for the uppermost layer in higher concentrations, where opacity and less absorption played more important roles for artists. Heade in particular

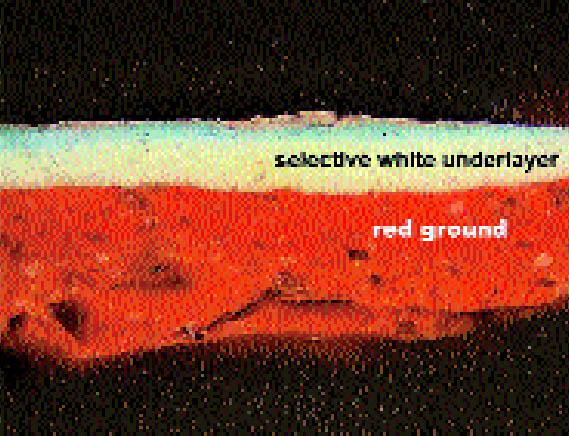

Some of the earlier portraits (Portrait of a Man, 1840, S2; Ruth Scarborough, ca. 1841, S5; and Mary Rebecca Clark) appear to have only one ground layer, a mixture of calcium carbonate and lead white. Of the 21 paintings analyzed, only Portrait of a Man and Ruth Scarborough were possibly primed by the artist. For Ruth Scarborough, a red earth ground received a selective layer of white paint before upper layers of paint were applied (fig. 3). Other materials were also noted in a number of paintings in the study. Electron microprobe analyses of Woodland Sketch (1863, S117) showed zinc white in the ground along with calcium carbonate and lead

The texture of the two-layer ground is generally smooth and even, with each layer approximately the same thickness. Exceptions are Roses and Heliotrope in a Vase on a Marble Tabletop (1862, S326) and Dawn (1862, S93), in which Heade experimented with a commercially prepared ground that was “pebbly” and reticulated (fig. 4). In other paintings, such as Cloudy Day, Rhode Island (1861, S87), either the ground or underlayer appears to be striated or textured, as detected through upper paint layers when viewed through a microscope. An interesting aspect that appears to have resulted from aging or drying is an “oozing” (fig. 5) originating from the ground or underlayer and coming through cracks of dried, upper paint layers. This effect is seen in early landscape paintings such as The Swing—Children in the Woods (1858, S48), Rhode Island Landscape (1859, S62), Lake George (1862, S95), and “Heliodore's Woodstar”and a Pink Orchid. It appears that the underlayers were not completely dry before the upper layers were applied, making the underlayer susceptible to oozing through cracks in the dried upper layers. A final notable occurrence in the ground layer,

The explanation for the occurrence of ground staining remains unresolved. Zucker has discussed three possible causes: the presence of lead acetate in the ground layer to promote drying; the possible addition of an oily coating on or excess oil content in the lead white upper ground layer that reacted with an inorganic metal (such as lead); and the reaction of lead with any carboxylic acid in the linseed oil paint to form lead stearate, a lead salt that has a lower refractive index than the lead white of the paint (Zucker 1999). Ground staining appears on prominent threads, where the paint is thin, almost transparent, and thus the uppermost threads of the dark, oil-saturated fabric become more visible. |