THE METHODS AND MATERIALS OF MARTIN JOHNSON HEADEELIZABETH LETO FULTON

ABSTRACT—This article presents the results of a study of paintings by the 19th-century American artist Martin Johnson Heade. The project was conducted at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which houses the largest public collection of Heade's paintings. Every major period of painting in Heade's career is represented here: portraiture, genre, land-scape, landscape–still life, and still life. The study included complete photodocumentation and technical examinations of 50 paintings, most from the permanent collection. Paint and ground layers including pigments of 21 paintings of this group were analyzed.Supports, grounds, and paint layers are described in an attempt to follow the progression of the artist's style through the years, including the influences of Heade's contemporaries. Photomacrography and cross sectional analysis were used to confirm and clarify Heade's application of ground and paint layers. Painting methods and materials and a variety of brush strokes and colors are also considered. Particular emphasis is given to pigments, with detailed analytical results presented in tabular form. TITRE—Les m�thodes et les mat�riaux utilis�s par Martin Johnson Heade. R�SUM�—Cet article pr�sente les r�sultats d'une �tude sur les peintures de Martin Johnson Heade, un artiste nordam�ricain du 19e si�cle. Ce projet a �t� r�alis� au Museum of Fine Arts (mus�e des beauxarts) de Boston, qui poss�de la plus importante collection publique de tableaux de Heade. Toutes les p�riodes importantes de l'oeuvre de Heade sont repr�sent�es ici: portrait, peinture de genre, paysage, paysage-nature morte et nature morte. Pour cette �tude, on a r�alis� la documentation photographique et l'examen technique complet de 50 tableaux provenant surtout de la collection permanente. Les couches de peinture et de pr�paration provenant de 21 tableaux appartenant � ce groupe ont �t� analys�es.Les toiles et les couches de pr�paration et de peinture sont d�crites afin d'esssayer de d�terminer la progression du style de l'artiste au fil des ans, y compris l'influence exerc�e par ses contemporains. Des photomacrographies et des �tudes de coupes stratigraphiques ont �t� employ�es pour confirmer et clarifier les fa�ons dont Heade appliquait ses couches de pr�paration et de peinture. Les techniques de travail, les mat�riaux employ�s et la gamme des coups de pinceau et des couleurs ont �t� �galement consid�r�s. Une importance particuli�re a �t� accord�e aux pigments et les r�sultats d�taill�s des analyses sont pr�sent�s dans un tableau. TITULO—Los m�todos y materiales de Martin Johnson Heade. RESUMEN—Este articulo presenta los resultados de un estudio de cuadros del artista americano del siglo XIX Mart�n Johnson Heade. El proyecto se llev� a cabo en el Museum of Fine Arts de Boston, que aloja la colecci�n p�blica mas grande de cuadros de Heade. Todos los periodos pict�ricos importantes en la carrera de Heade est�n representados all�: retratos, genero, paisaje, paisaje con naturaleza muerta y naturaleza muerta. El estudio incluye documentaci�n fotogr�fica completa y ex�menes t�cnicos de 50 cuadros, la mayor�a de ellos de la colecci�n permanente. Se analizaron capas de pintura y de preparaci�n, con pigmentos provenientes de 21 cuadros de este grupo.Se describen los soportes y las capas de pintura y de preparaci�n, en un intento de seguir el desarrollo del estilo del artista a trav�s de los a�os, incluyendo las influencias de los contempor�neos de Heade. Se usaron an�lisis fotocromatogr�ficos y de cortes transversales para confirmar y esclarecer la aplicaci�n de la preparaci�n de las capas de pintura en Heade. Se consideraron tambi�n los m�todos y materiales de su pintura y una variedad de pinceladas y colores. Se di� particular �nfasis a los pigmentos, con los resultados anal�ticos detallados presentados en forma de tabla. 1 INTRODUCTIONThis article focuses on the findings of a collaborative technical research project on 50 paintings by Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904). This study, funded To contribute further criteria for dating paintings and possibly to aid in authentication, the project attempts to describe and document the evolution of Heade's painting technique and to establish a chronology of the materials he used. However, the study involves 50 paintings (see appendix 1), the majority of them from the permanent collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. This body of work is less than 10% of extant paintings ascribed to Heade. The exact number of his paintings is unknown, but to date 630 paintings are documented from his 60-year career. Those that were studied included paintings that spanned his entire career, but primarily from the 1860s and 1870s. In the first half of the study beginning September 1996, paintings were brought into the paintings conservation studio for a systematic examination and extensive photodocumentation, which included infrared reflectography and study under ultraviolet illumination. Thirty-five mm slides were taken of the entire paintings as well as of details. Photomicrographs (also 35 mm) documenting condition and painting techniques were also taken at this time. Once the paintings were examined, reports were written and entered into a database to which conservators and art historians could refer. The second half of the research, which began in March 1998, consisted of review and analyses of 21 of the initial 50 paintings. The 21 paintings were chosen largely because they are dated or are of particular interest; i.e., they are pivotal paintings or anomalies in the normal trend found within a given period. These paintings were analyzed for pigment identification using electron microprobe analysis, Fourier transform infrared microspectrometry (FTIR), x-ray fluorescence (XRF), polarized light microscopy (PLM), and ultraviolet illumination examination (UV). Analytical techniques are discussed in more detail in appendix 2. Media analyses were not conducted in this study. Sample sites for all pigments were chosen largely for their interest or purity of colors to determine overall palette or color mixes in areas of multiple layers. In some cases pigments could not be determined by the above methods, and their results are not published in this article. The results presented in appendix 3 are those that were generally definitive of the group of 21 chosen for analysis. 2 HISTORICAL BACKGROUNDIt appears that Heade used materials for painting that were widely available. Although he probably apprenticed with Edward Hicks (1780–1849) (Stebbins 2000), there is no evidence that he received any formal or academic training. Instead, he learned as he worked, traveling in America and Europe and incorporating into his repertoire the methods he admired most in other artists' paintings. He was a cautious, calculating, and steady painter, if one can judge from his working methods. Although some drawings and approximately two dozen oil studies exist, Heade seemed generally to develop his compositions on the canvas he was painting rather than using separate oil sketches or compositional drawings. He would start with a schematic, simple drawing of the background such as a horizon or a table edge, sometimes adding more detailed drawings of major elements, painting the forms and then adjusting and precisely balancing the composition by modifying the size and shape of the motifs. Once Heade perfected the desired motif, he would add it to his repertoire, using it repeatedly in other paintings. He used this method of repeated motifs most regularly in his flower paintings of apple blossoms, orchids, and, later in his career, Cherokee roses and magnolias. English Pre-Raphaelites, whose work Heade had possibly seen in the English Art in America exhibition in Philadelphia, New York, or Boston in 1857–58, as well as American Pre-Raphaelites, whom he met in the 10th Street Studio Building in New York, had an early and notable influence on him (Stebbins 1975, 2000). His early landscapes, from 1858, demonstrate the influence of both English and American Pre-Raphaelites. We note his “use of high-keyed colors, crisp painting, and equal emphasis of foreground and background detail [that] is characteristic of Luminism Another influence on Heade was the methods and style of artists in the 10th Street Studio, New York City, where Heade lived and worked for a number of years. In this studio-residence building he was in contact with his neighbors Sanford Gifford (1825–1880), James M. Hart (1828–1901), William Jacob Hays (1830–1875), John Henry Hill (1839–1922), William J. Stillman (1828–1920), John F. Kensett (1816–1872), and Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), to name a few (Blaugrund 1997, 133–34). Few records exist indicating Heade's purchase of artist's materials, so most of the following information is taken from the paintings themselves. The materials with which Heade worked were generally those that were produced by American manufacturers. In addition to materials produced in America, such as the F. P. Pfleger patented stretcher on “Heliodore's Woodstar” and a Pink Orchid (ca. 1875–90, S487),1 he also used materials that were imported into the United States from European manufacturers, such as the British manufacturer Winsor & Newton, and distributed in New York and Boston. Examples of Winsor & Newton materials are found in Flowers in an Ornate Vase (1874, S446, Winsor & Newton board), Flowers in a Frosted Vase (ca. 1874–80, S449, Winsor & Newton board), and Cattleya Orchid and Three Brazilian Hummingbirds (1871, S429, Winsor & Newton mahoghany panel). With very few exceptions, Heade used prestretched, preprimed canvases on keyable stretchers. Many of the paintings studied were lined, so canvas stamps were not visible. Although Heade's choice of light-colored, preprimed canvases seems almost conventional given what was available, his understanding of the role that the ground played was quite sophisticated. He was able to take full advantage of the bright, reflective quality of the ground material necessary for imbuing his paintings with light. The only known record of Heade's observations on colors mentions verdigris, lemon yellow, cadmium, emerald green, and Italian pink. His palette changed in the late 1850s and early 1860s when many new pigments became available (Wright 1999, 177). 3 SUPPORTSIn the larger group of 50 paintings examined, eight had original, intact canvas supports, which had never been removed from their stretchers. No canvas stamps were visible. In some cases, in the four corners seen from the reverse, small “tabs” of preprimed canvas were folded over the stretchers and tacked onto the reverse (fig. 1). This method of stretching is not unique to Heade's work. Similar tabs have also been found on canvases of many late-19th-and early-20th-century Boston-based painters, such as Dennis Miller Bunker (1861–1890).

Most of the canvases examined during this study were the medium-weight, plain weave, linen-type canvases most commonly used by artists of the mid-to late 19th century. However, Heade occasionally used a double-threaded, rep weave canvas, as seen in Mary Rebecca Clark (1857, S43). He also used a rep weave canvas with single threads in one dimension and double threads in the other, as seen in The Stranded Boat (1863, S111) and Newburyport Marshes (ca. 1866–76, S142). Twill canvas was found in Rocks in New England (1855, S60) and Becalmed, Long Island Sound (1876, S248). Heade preferred a 1:2 proportioned format—the horizontal panorama—for his landscapes and seascapes. The same format was also found in work by artists such as Francis A. Silva (1835–1886) and Alfred T. Bricher (1837–1908), but not as consistently as with Heade. The 1:2 format was also found in some of Heade's still lifes not only in the horizontal but also in the vertical orientation, as in Orchids and Spray Orchids with Hummingbirds (ca. 1875–90, S497). The landscapes and seascapes examined were painted on canvas typically tacked to four-or five-member, keyable wooden stretchers. In addition to the canvases, a few paintings were painted on artist's board. Although none were included in the study, we have also seen several paintings on mahogany panel. 4 GROUNDSHeade must have been aware of the aesthetic importance of a bright ground in his paintings, as he exploited the effect of reflectance through thin paint layers, rendering brilliant colors in his paintings. The majority of the paintings in this study are painted on smooth, light-colored (off-white, tan, or gray) grounds that were commercially applied in two layers. This two-layer-type ground is probably the type referred to as the “most commonly encountered commercially prepared ground structure in 19th-century American paintings” (Zucker 1999, 6). Both layers contained a mixture of calcium carbonate and lead white, but the upper layer contained a higher percentage of lead white (fig. 2). The apparent reason for this mixture may have been economic: calcium carbonate mixed with lead white in the lower layers was cheaper than pure lead white, which was reserved for the uppermost layer in higher concentrations, where opacity and less absorption played more important roles for artists. Heade in particular

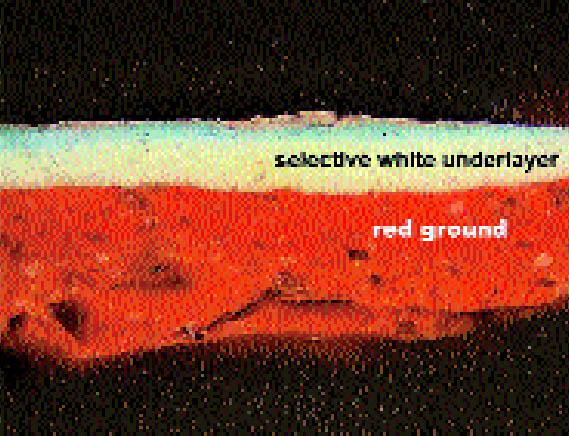

Some of the earlier portraits (Portrait of a Man, 1840, S2; Ruth Scarborough, ca. 1841, S5; and Mary Rebecca Clark) appear to have only one ground layer, a mixture of calcium carbonate and lead white. Of the 21 paintings analyzed, only Portrait of a Man and Ruth Scarborough were possibly primed by the artist. For Ruth Scarborough, a red earth ground received a selective layer of white paint before upper layers of paint were applied (fig. 3). Other materials were also noted in a number of paintings in the study. Electron microprobe analyses of Woodland Sketch (1863, S117) showed zinc white in the ground along with calcium carbonate and lead

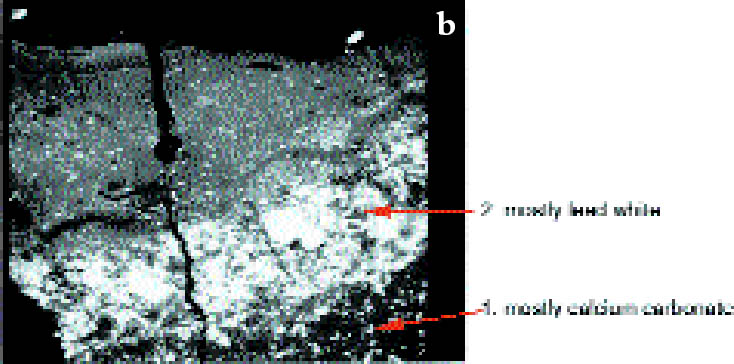

The texture of the two-layer ground is generally smooth and even, with each layer approximately the same thickness. Exceptions are Roses and Heliotrope in a Vase on a Marble Tabletop (1862, S326) and Dawn (1862, S93), in which Heade experimented with a commercially prepared ground that was “pebbly” and reticulated (fig. 4). In other paintings, such as Cloudy Day, Rhode Island (1861, S87), either the ground or underlayer appears to be striated or textured, as detected through upper paint layers when viewed through a microscope. An interesting aspect that appears to have resulted from aging or drying is an “oozing” (fig. 5) originating from the ground or underlayer and coming through cracks of dried, upper paint layers. This effect is seen in early landscape paintings such as The Swing—Children in the Woods (1858, S48), Rhode Island Landscape (1859, S62), Lake George (1862, S95), and “Heliodore's Woodstar”and a Pink Orchid. It appears that the underlayers were not completely dry before the upper layers were applied, making the underlayer susceptible to oozing through cracks in the dried upper layers. A final notable occurrence in the ground layer,

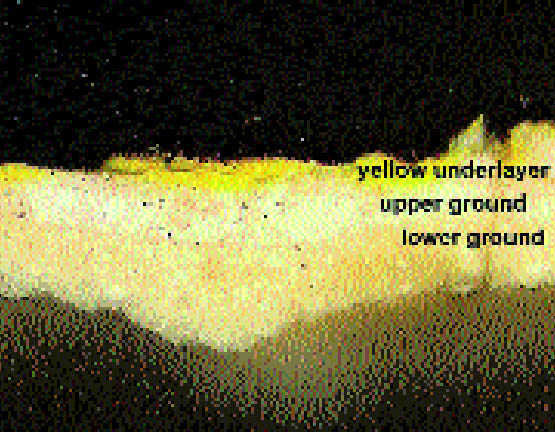

The explanation for the occurrence of ground staining remains unresolved. Zucker has discussed three possible causes: the presence of lead acetate in the ground layer to promote drying; the possible addition of an oily coating on or excess oil content in the lead white upper ground layer that reacted with an inorganic metal (such as lead); and the reaction of lead with any carboxylic acid in the linseed oil paint to form lead stearate, a lead salt that has a lower refractive index than the lead white of the paint (Zucker 1999). Ground staining appears on prominent threads, where the paint is thin, almost transparent, and thus the uppermost threads of the dark, oil-saturated fabric become more visible. 5 UNDERLAYERSImprimatura plays an important role in Heade paintings, setting an overall atmospheric tone in outdoor landscapes and seascapes. In some of his work, Heade chose to use an imprimatura selectively or continuously, depending on the effect he wanted to create. One of the more prominent examples can be seen in the eerie atmosphere created in Approaching Storm. In this painting, cross section sampling was performed on all four edges in search of a continuous undertone. It appears that an acid, greenish yellow imprimatura (fig. 6) was present overall, loading the image with a feeling of tension. The predominant yellow pigment analyzed in this painting is lead chromate yellow. In other paintings, such as Hunters Resting (1863, S114), a warm pink imprimatura imparts a restful feeling of comfort in the glow of autumn sunlight as seen by the subjects after a day of hunting outdoors. In April Showers, Heade employed a prominent, dark gray-brown imprimatura (Wright 1999) to create an ominous atmosphere.

6 PRELIMINARY DRAWINGSince drawing would have been a fundamental part of the training for any formally educated painter, many theories pertaining to methods of sketching and drawing were available to painters of mid-19th-century America. Instruction manuals such as J. G. Chapman's American Drawing Book (1847) and John Ruskin's Elements of Drawing (1857), along with published material on the theory and practice of painting, were widely distributed and may have been studied by Heade. However, with no documentation or records of his owning particular manuals, it is difficult to ascertain whether he actually pursued published instruction on the subject. Relative to the number of extant paintings, few sketchbooks and drawings by Heade exist. One journal Heade kept during a six-month stay in Brazil from September 1863 until the following spring is housed at the MFA, Boston (Brazil-London Journal 1863, S623). Interspersed sporadically in the text (in which he recounts his day-to-day experiences in Heade generally began his compositions with a schematic preliminary drawing on the ground layer. Often he simply suggested the horizon or a topographical profile of the backdrop scene. In many instances he drew motifs within the pictorial scene using varying degrees of detail. Trailing Arbutus (1860, S322), Roses and Heliotrope in a Vase on a Marble Table-top, and Shore Scene: Point Judith (1863, S119) (fig. 7) are relatively rare examples in which Heade used extensive detailed drawing throughout the composition. Although Heade used a variety of media for his preliminary drawings, throughout his career he seems to have preferred dry materials (i.e., pencil, charcoal, chalk, and crayon). When the paintings are examined under the microscope (fig. 8) or with infrared reflectography, these media are occasionally seen near contours or through paint glazes. Where a dry under-drawing medium has been found, it has been difficult to analyze chemically. Occasionally loose, unbound black particles were seen between the ground and paint layers in some of the paint cross sections of the orchids when viewed through the microscope. In the landscapes and seascapes, when a dry medium was used, it is most commonly found in the horizon line and in outlines for hill and mountain silhouettes. In these paintings, with very limited underdrawing, there is an increased number of pentimenti, especially in the upper paint layers of the contours of the various compositional elements. The pentimenti range from very subtle changes in the trees, haystacks, orchids, or heads of the humming-birds to actual displacement of the various motifs. Although the dry underdrawing is more common, Heade sometimes used a wet medium. He would complete underdrawings of specific motifs such as birds or foliage using either a carbon-based ink (fig. 9) or thin, raw umber-colored paint. Observed using infrared reflectography or a binocular microscope, these areas could be characterized as

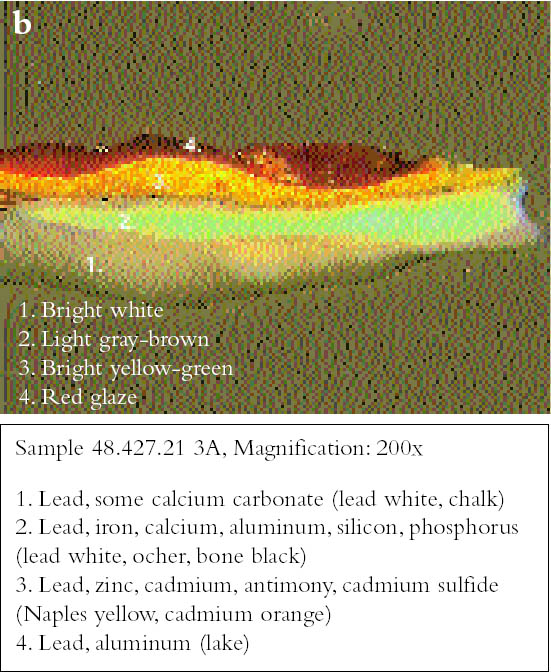

In addition to, or sometimes in combination with, the black underdrawing materials, a red crayon-like material was found below the paint layers in compositions containing apple blossoms, orchids (“Heliodore's Woodstar” and a Pink Orchard), Cherokee roses (Branches of Cherokee Roses, ca. 1883–88, S551), and magnolias (Two Magnolias and a Bud on Teal Velvet, ca. 1885–95, S593). The red material, seen with the naked eye or through the microscope at the edges of the flowers (fig. 10), may be indicative of replication and transfer of the outlines of blossoms from one composition to the next. The red occurs as a line at the edges of flowers that are almost identical in size and shape to the flowers in other compositions. One possible copy method available to Heade was advertised in the popular art journal Crayon as “Magic Impression Paper for … Copying Leaves, Plants, Flowers … will also mark linen. … Each package contains four different colors: Black, Blue, Green and Red, with full printed instructions, for all to use, and will last sufficiently long to obtain five hundred distinct impressions” (Durand 1855, 94). Another possibility is that, as Ruskin suggested in The Elements of Drawing, Heade could have drawn the lines with red crayon material and then modified the drawing to his satisfaction with a more permanent medium, such as graphite. But the possibility remains that Heade could have simply executed the drawings freehand in the red crayon material. Because non-carbon-based drawing between paint layers is very difficult to detect, conclusions remain elusive and hypothetical. Later in his career it seems that Heade used the red drawing as a design element. In certain areas in Like many Victorian artists who kept a collection of props from which to draw or paint, Heade owned skins of hummingbirds. Judging from the infrared reflectograms of the hummingbirds, one could hypothesize that, rather than drawing them completely, Heade was comfortable using cursory underdrawings of the birds, fully defining them in paint. As with the orchids, magnolias, and apple blossoms, the size and shape of the various species are repeated in many paintings. The question still remains whether Heade used a mechanical means of transferring the motifs, traced the motifs, or drew them free-hand with or without the aid of an optical device. 7 PAINTING TECHNIQUESIn the 1840s, in the beginning of his career, Heade painted mostly with a paste vehicular paint in a simple structure. The paint layer from this period is generally smooth with slight impasto in the more thickly painted areas. By the late 1850s and into the 1860s, as Heade became more accomplished, he experimented more with impasto, even becoming almost Impressionistic, as in April Showers(fig. 11). During this period Heade added to his repertoire a vocabulary of technical language not seen in his paintings prior to 1858. His paint structure became multilayered as his style became more sophisticated. In addition, Heade experimented with many unique brush strokes and techniques that would become the hallmarks of his style in the 1860s. One of the most characteristic techniques Heade developed was glazing over bright, reflective impasto to imbue his subjects with light. This technique is well illustrated in Sunset on Long Beach (ca. 1867, S176) (fig. 12). In using this device to paint areas that served the purpose of emanating light, Heade applied a thick underlayer of bright, reflective white paint impasto. On top of this thick white underlayer, he generally applied thin, transparent glazes of red, orange, and yellow (for the clouds, sunsets, sunrises, and throats of orchids); transparent reds, purples, greens, and blues can also be seen in some of the hummingbirds. These Luminist effects work well because the bright white underlayer reflects light through the glazes, much like light passing through stained glass, emitting a luminosity and intensity of color not achievable by opaque paints mixed with white on the palette. This technique was first noted in 1858 in The Swing—Children in the Woods and became further refined, reaching its pinnacle in his sunsets, orchids, and hummingbirds (Wright 1999). The year 1858 was also when Heade was exposed to the Pre-Raphaelites, who were known to work with these “stained-glass” effects (Sheldon 1998) and appears to be the seminal year for this technique that Heade transforms into a device all his own, giving intensity to the clouds, sunsets and sunrises, orchids, and hummingbirds. Heade used other characteristic technical devices to emphasize certain qualities in his paintings. To emulate the feeling of a lowland estuary in his land-scapes, which were extremely horizontal in format, Heade used long, adjacent horizontal brush strokes of complementary colors (usually dull reds and greens) to add interest to otherwise monotonous areas (fig. 13). He contrasted the horizontal, flat middleground with detailed vegetation in the form of stippled or spiked plants, sometimes punctuated with flecks of bright colors, a technique most likely borrowed from Church (fig. 14) (Wright 1999, 175). Heade added these bright flecks to dark or neutral areas, often using complementary colors. This technique is later fully expressed in his hummingbirds and orchids that are also surrounded in the background by muted complements to further intensify the brilliant colors of the subjects. In addition, as April Showers illustrates, a stippling effect fully developed in Heade's blossoming trees, which very often flank the smooth middleground (see fig. 11). Other techniques found in Heade's land-scapes include comma-like brush strokes, subtractive strokes (using something stiff like the brush ferrule to remove paint from the center of the stroke), and distinctive, calligraphic, hooked branches, commonly found in his hummingbird pictures. In many landscapes glazing is often found in the shadows surrounding the base of trees, rocks, or other compositional elements. Scumbling, which plays a

8 PALETTEThe palette Heade used during his early years was limited to what was available in the second quarter of the 19th century. This range is exemplified in Portrait of a Man from the 1840s, in which his palette consisted of lead white, bone black, red ocher, yellow ocher, and Prussian blue. Browns were mixed from these above-mentioned pigments. The greens in the painting, as in other Heade paintings, were a mixture of yellows and blues rather than distinct green pigments. Heade's choice for green may have resulted from a lack of availability of green pigments in the early 19th century, but he often continued the practice of mixing blue and yellow even after a variety of synthetic greens came on the market in midcentury. By the 1850s Heade used a wider variety of pigments. As they became available, Heade used synthetic greens and continued using mixtures of yellows and blues. In our study of Rocks in New England, we detected the relatively “new” pigment emerald green (1820s) as well as artificial ultramarine, introduced to his palette in these early landscapes. Another pigment found in this painting, which Heade started to use by the 1850s, was a transparent, organic, resinous brown. The specific identity of this pigment is unknown at this time. The earliest use of cadmium yellow in our study is found in the gold crucifix necklace in Mary Rebecca Clark, which also contains the earliest use of vermilion as well as a zinc-containing pigment, probably zinc white. As mentioned earlier, Heade began to use new colors and glazing techniques in The Swing—Children in the Woods. In the glazes here, we see for the first time in our study Heade's use of the transparent pigments (fig. 15) such as a red lake as well as an application of Prussian blue. In this painting, we also found evidence of barium chromate. In later paintings, the yellows Heade widely used were barium chromate, strontium chromate, lead chromate, and zinc chromate. Other yellow and green pigments found only occasionally in the study were viridian and zinc yellow. Later paintings, such as “Heliodore's Woodstar” and a Pink Orchid also tested positive for cobalt yellow, which was mixed with Prussian blue to produce the cool green seen in the leaves of the orchid. After the early 1860s, Heade generally did not change his palette. Vase of Mixed Flowers demonstrates the widest variety of pigments in any one painting in our study. In this painting Heade also continued the practice of glazing rather than mixing to produce odd color combinations (fig. 16), as seen in a cross section from the diamond pattern of the purple-brown background, where a dark red glaze was applied over an olive green paint mixture. The results of all the analyses for the pigments are presented in appendix 3. 9 VARNISHES AND FRAMESSince few original varnishes exist on the paintings, and those that do proved difficult to analyze, it was impossible to determine Heade's general preference for varnish. However, results from a painting whose coatings are believed to be original tested as a thin application of a natural resin, most likely a dammar. Several paintings from the early 1860s also seem to have had an original oil varnish, based on solubility tests. It is safe to say that Heade wanted his paintings to be varnished. Several of the paintings studied are in their original frames (Stebbins 2000), and a few of these paintings were displayed in original shadow boxes. 10 CONCLUSIONSThis article presents the results of the first broad study on the materials and methods of oil paintings by Martin Johnson Heade. Heade is unique in that his career began before the industrial and commercial revolution had a major impact on artist's methods. His career evolved through the late 19th to the beginning of the 20th century, painting in all genres: still lifes, portraits, landscapes, marines, and a few As with any project, the most wonderful discoveries are new and better-formed questions. It is our hope that further studies will provide deeper understanding in the following areas of research: media analysis, original varnishes, reasons for ground staining and drying problems in the paint, underdrawing methods, and, specifically, Heade's possible use of mechanical means of transferring motifs from painting to painting, his relationship to photography, the influence of artists such as Thomas and Edward Hicks, Frederic E. Church, the Pre-Raphaelites, and Heade's use of artist's manuals. This research project coincided with the completion of Theodore E. Stebbins Jr.'s grand opus The Life and Work of Martin Johnson Heade (2000) and the exhibition Martin Johnson Heade, which was organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, opened in September 1999 at the MFA, traveled to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., in the spring of 2000, and closed at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in August 2000. In preparation for these projects, we were able to augment and confirm our findings by studying many other paintings by Heade (some newly identified) not in the MFA's extensive collection, including some of his most important and beautiful works. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe authors would like to express their gratitude to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation for having largely funded this research project. The importance of working collaboratively with a team of experienced and knowledgeable conservators, scientists, and curators cannot go without mentioning. From the curatorial Department of Art in the Americas we thank former chair of American paintings Ted Stebbins, who has brought to the study 35 years of Heade expertise in addition to the exhibition catalog and catalogue raisonn�. Many thanks to Karen Quinn and Janet Comey, who were contributing authors to the exhibition catalog and brought their own unique and insightful perspectives to the study of Heade paintings. Additionally, we would like to thank Carol Troyen, curator of American paintings, for her contributions to the editing process. In the Conservation Division, we are grateful to conservation scientist Michele Derrick for her help in the analysis of pigments. Previous to this study, many of the paintings had been analyzed using x-ray fluorescence, an analytical technique performed largely by Kate Duffy with Richard Newman in 1993 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Also in the early 1990s at the MFA, Rita Albertson and others did seminal research into Heade's techniques, especially focusing on the oil sketches and their relation to finished paintings. We would like to acknowledge Leane Delgaizo, collections care specialist, and Andrew Haines, assistant conservator of frames, who were responsible for the transport and framing/unframing of the paintings in the study. We would also like to thank Rhona MacBeth for her technical help with infrared and computer imaging, and Devi Ormond, a visiting paintings conservation intern who assisted in the technical research. We are also grateful to Arthur Beale, chair of conservation and collections management at the MFA, Boston, for his support. NOTES1. The “S” number refers to the catalog number in Stebbins 2000. APPENDIXAPPENDIX 1: PAINTINGS EXAMINED

APPENDIX 2: ANALYTICAL TECHNIQUES FOR PIGMENT IDENTIFICATIONThe techniques utilized for pigment identification in this project were nondestructive energy dispersive x-ray fluorescence (XRF), electron probe microanalysis (EPMA), Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy (FTIR), and polarizing light microscopy (PLM). Nondestructive XRF was used to survey different brightly colored areas of many of the paintings. The custom-built instrument consists of an Ortec Si(Li) detector operated by a HNU System 5000 spectrometer; a 1 mm collimated x-radiography tube (continuum tungsten radiation) is utilized as the excitation source. The XRF system can detect calcium and all heavier elements in the periodic table and is a valuable tool in helping to identify many inorganic pigments. It rarely provides definitive pigment identification, however, since many elements detected can point to more than one specific pigment. Small scrapings were taken from the paintings in order to provide more detailed information on the pigments, and it is these results that are reported in this article and the summary table (appendix 3). A portion of each sample was pressed between the diamond windows of a Spectra Tech “Micro Sample Plan.” One or both of the windows, with adhered sample, were studied by PLM to note the number of different types of pigments present. The PLM permitted some inorganic pigments to be identified with confidence and the presence of organic pigments (such as red lakes) to be noted. The pressed sample was then analyzed by FTIR microspectroscopy utilizing a Nicolet 510P FTIR spectrometer with an attached NicPlan IR microscope. The microscope apertures were adjusted to frame analysis areas that varied from about 20 μm across to 60 μm across. Generally, several areas in each pressed sample were analyzed, with areas containing different individual pigment particles or clusters of particles being chosen. Specific identifications of organic and inorganic compounds are based on comparison of the FTIR spectra with several commercial databases and in-house libraries. FTIR analysis can readily establish the presence of many different kinds of polyatomic anions (such as sulfate, carbonate, and chromate) and can provide specific identifications of individual compounds within these classes. In the case of carbonates, for example, calcite, cerussite (present in many lead whites), hydrocerussite (also found in many lead whites), and numerous others can be positively identified, either alone or in mixtures. To name one other example, the different chromate-containing yellow pigments (zinc, barium, lead, and strontium) can also be distinguished on the basis of their FTIR spectra (an excellent general reference to the utilization of IR spectroscopy for inorganic compound identification is Farmer 1974). However, some pigments do not have IR spectra, for example, the cadmium colors, vermilion, and zinc white. To supplement the FTIR data and provide important elemental information on pigments that do not have IR spectra, a second portion of many of the paint scrapings was analyzed by qualitative energy dispersive x-ray fluorescence in a Cameca MBX electron beam microprobe (Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Harvard University). In some cases, cross sections were prepared, and the micro-probe analyses were carried out on these. This instrument can detect sodium and all higher elements. Individual pigment particles as small as a few μm can easily be visualized by back-scattered electron imaging and then analyzed in the instrument. Finally, some dispersed pigment slides were also prepared in Cargille Meltmount and examined by PLM. These slides were superior to the samples pressed on the diamond window for careful micro-scopic examination, and they also provide a permanent record of the sample. The combination of procedures outlined here, sometimes supplemented by powder x-ray diffraction, It should be noted that, although not discussed here, the FTIR analyses also provide basic information on the paint media. In this study, without exception, FTIR spectra indicated that Heade used oil paints. A more detailed study of the oil, and possible additives such as natural resins, would require chromatographic techniques, which we did not utilize for the research project reported here. APPENDIX 3: ANALYTICAL RESULTS

REFERENCESBlaugrund, A.1997. The Tenth Street Studio Building: Artist-entrepreneurs from the Hudson River School to the American Impressionists. Southampton, N. Y.: Parrish Art Museum. J. G.Chapman. 1847. American drawing book: A manual for the amateur, and basis of study for the professional artist: Especially adapted to the use of public and private schools, as well as home instruction. New York: J. S. Redfield. Durand, A. B.1855. Letters on landscape paintings: Letter 1. Crayon1, no. 6 (Jan. 3):1. Farmer, V. C., ed.1974. The infrared spectra of minerals. London: Mineralogical Society. Ferber, L. S., and W. H.Gerdts. 1985. The new path: Ruskin and the American Pre-Raphaelites. Brooklyn, N. Y.: Brooklyn Museum and Schocken Books. Ruskin, J. [1857], and B.Dunstan. 1991. The elements of drawing, illustrated edition with notes by Bernard Dunstan,ed. B.Dunstan. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. Sheldon, L.1998. Methods and materials of the PreRaphaelite circle in the 1850s. Painting techniques: History, materials and studio practice. Contributions to the Dublin Congress. Dublin: IIC. Stebbins, T. E.1975. The life and work of Martin Johnson Heade. New Haven: Yale University Press. Stebbins, T. E.2000. The life and work of Martin Johnson Heade. New Haven: Yale University Press. Wright, J.1999. The development of Martin Johnson Heade's painting technique. In T. E. Stebbins, Martin Johnson Heade. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. 169–83. Zucker, J.1999. From the ground up: The ground in 19th-century American pictures. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation38:3–20. FURTHER READINGBomford, D., J.Kirby, J.Leighton, and A.Roy. 1990. Art in the making: Impressionism. London: National Gallery Publications Limited. Cash, S.1994. Ominous hush: The thunderstorm paintings of Martin Johnson Heade. Fort Worth, Texas: Amon Carter Museum. Feller, R. L., and R. M.Johnson-Feller. 1997. Vandyke brown. In Artists' pigments: A handbook of their history and characteristics, Vol. 3, ed. E. W.FitzHugh. Washington, D. C.: National Gallery of Art. 157–90. Fiedler, I., and M.Bayard. 1997. Emerald green and Scheele's green. In Artists' pigments: A handbook of their history and characteristics, Vol. 3, ed. E. W.FitzHugh. Washington, D. C.: National Gallery of Art. 219–71. Gettens, R. J., and G. L.Stout. 1966. Painting materials: A short encyclopaedia. New York: Dover Publications. K�hn, H., and M.Curran. 1986. Chrome yellow and other chromate pigments. In Artists' pigments: A handbook of their history and characteristics, Vol. 1, ed. R. L.Feller. Washington, D. C.: National Gallery of Art. 187–217. Newman, R.1997. Chromium oxide greens: Chromium oxide and hydrated chromium oxide. In Artists' pigments: A handbook of their history and characteristics, Vol. 3, ed. E. W.FitzHugh. Washington, D. C.: National Gallery of Art. 273–93. Plesters, J.1993. Ultramarine blue, natural and artificial. In Artists' pigments: A handbook of their history and characteristics, Vol. 2, ed. A.Roy. Washington, D. C.: National Gallery of Art. 37–65.

Stebbins, T. E.1999. Martin Johnson Heade. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. AUTHOR INFORMATIONELIZABETH LETO FULTON is an associate conservator of paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and she also works part-time in private practice. She was assistant conservator of paintings at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum from 1996 to 2001. She has a B.A. in Italian studies, with emphasis in art history, from the University of Connecticut, 1985, and an M.A. and a certificate of advanced study in art conservation from the State University of New York, College at Buffalo, 1994. She started her conservation training in Florence, Italy, where she received certificates from the Universita' Inter-nazionale dell' Arte and the Associazione Fiorentina, 1986. She has completed postgraduate internships in paintings conservation at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1995, and Straus Center for Conservation at Harvard University Art Museums, 1994, and she has worked as a student intern at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, 1993, the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., 1992, and Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut, 1990–91. Address: Paintings Conservation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 465 Huntington Ave., Boston, Mass. 02115. RICHARD NEWMAN is head of scientific research at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He has a B.A. in art history from Western Washington University, 1974, and an M.A. in geology from Boston University, 1983. He received a certificate for completion of a three-year apprenticeship, specializing in conservation science, at the Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, 1980. He worked as both a conservation scientist and assistant conservator of sculpture and objects at the Fogg Art Museum from 1980 to 1986, and since 1986 he has worked at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Address as for Fulton. JEAN WOODWARD is an associate conservator of paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where she has been on the staff since 1975 (working under Elizabeth Jones, 1975–79, and under Alain Goldrach, 1980–87). She has worked extensively on both European and American paintings. In the American paintings collection she has studied or treated in depth many 18th-and 19th-century paintings and has been involved with the Heade project since its inception in 1992. She has a B.A. in art history from Goucher College, 1961, and she completed the three-year apprenticeship program in conservation, specializing in paintings conservation, at the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, in 1964. Address as for Fulton. JIM WRIGHT is the Eyk and Rose-Marie van Otterloo Conservator of Paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and head of paintings conservation, 1992 to present. He was conservator of paintings at the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco from 1987 to 1991 (head of paintings conservation, 1989–91) and held various conservation positions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco from 1982 to 1987 (intern, assistant conservator, and associate conservator). He received a B.A. in art history and philosophy from Saint Louis University, 1977, and an M.A. and certificate of advanced study from the State University of New York, College at Oneonta, New York (Cooperstown Graduate Program in Conservation), 1983. Address as for Fulton.

Section Index Section Index |