EVOLVING EXEMPLARY PLURALISM: STEVE MCQUEEN'S DEADPAN AND EIJA-LIISA AHTILA'S ANNE, AKI AND GOD—TWO CASE STUDIES FOR CONSERVING TECHNOLOGY-BASED INSTALLATION ARTMITCHELL HEARNS BISHOP

2 EXAMPLES OF TECHNOLOGY-BASED INSTALLATION ARTUnder discussion are Steve McQueen's Deadpan(fig. 1) and Eija-Liisa Ahtila's Anne, Aki and God (figs. 2–3), both on display in Seeing Time: Selections from the Pamela and Richard Kramlich Collection of Media Art at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) in 1999–2000 (for more on the artists, see References and Further Reading). Steve McQueen was present for the discussion of his work during the TechArchaeology Symposium. Also present were Colin Griffiths, a media arts specialist who oversees the installation of James Coleman's (b. 1941) works and works of other artists; Robert Riley, the curator of media arts at SFMOMA when the show was mounted; and Michelle Barger, conservator of objects at SFMOMA. Neither McQueen nor Ahtila was satisfied with installations in Seeing Time. The reasons for their dissatisfaction will be explained, but the causes will be explored only briefly and not definitively. SFMOMA has done a great deal to try to create dialogues and procedures to prevent problems (Sterrett and Christopherson 1998), but with the best of intentions, things can go wrong, and we can only learn from the problems. 2.1 STEVE MCQUEEN'S DEADPANDeadpan is described in the catalog for the exhibition as follows: When viewing the piece, viewers find it difficult not to wince, anticipating a rush of air or sound that would accompany the collapsing wall. One tends to share an almost visceral sympathy with the artist after viewing the piece for any length of time.

A disturbing discovery by the artist proved to be extremely useful for purposes of discussion during the symposium and for this article, as it highlights the difficulties associated with technology-based installation art. Deadpan was squeezed during installation so that it was 5 in. narrower and 15 in. higher, creating an overall effect of elongation. The reasons for this problem were discussed at length, and in the end, it seemed that perhaps due to conflicting instructions or the exigencies of fitting a complex show into the galleries, the work was squeezed during the installation process. A conflict appears between the instructions provided by McQueen's gallery and SFMOMA's registration records. Instructions provided by Steve McQueen's gallery were as follows:

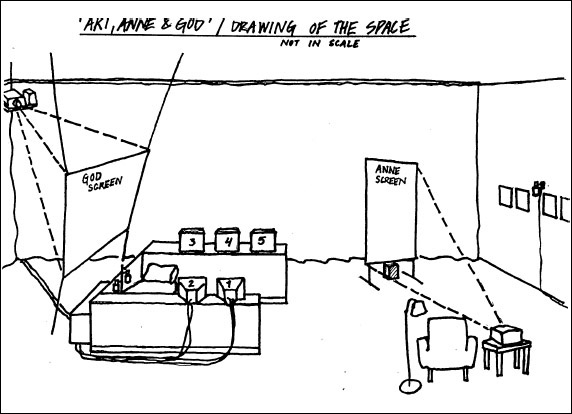

However, the notes field in SFMOMA's database entry for the piece (PK1998.05) state the following; “At MOMA: SONY 1271 three-gun video projector, not included with work of art. Room size: 13'9” Wide x 23'10” Long; but depends on the projector and lens, image variable but size to fill wall. ” It is also possible that the usual metric conversion demons that plague Europeans in the United States were at work. A precise conversion of 6 m to feet and inches on World Wide Metric Company's website (www.worldwidemetric.com/metcal.htm) works out to 19.585 ft. (236.220 in.) and 4 m to 13.1234 ft. (157.480 in.), or shall we say 19 x 13 ft.? What seems perfectly clear and simple in one country is not necessarily simple or clear in another, even when two countries appear to speak the same language. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration's $12 million Mars Climate Orbiter was lost in 1999 due to metric conversion errors. Understandably, this fact was no comfort for Steve McQueen when he discovered the problem. The artist would also have preferred a ceiling height just above the screen, as described in the instructions, but SFMOMA was unable to provide this height due to fire codes that mandated a clear spray area for fire sprinklers. Unlike some of the artists with pieces in the show, Steve McQueen was not present to monitor the installation and was unable to have a representative present to do so. McQueen felt that this problem detracted from the installation to such a degree that he would have preferred it not be shown as it was installed at SFMOMA. The following questions guided discussion during the symposium. 1. What types of procedures are most effective when examining the work? With Deadpan, examination procedures required that those responsible for the work ensure that the aesthetic experience specified by the artist is in place at installation and maintained. The equipment specified for the piece is either a Barco 808 or a Sony VP 2. What is essential to determining origins and authenticity of the work? The authenticity of Deadpan depends on fidelity to the artist's aesthetic intent for the installation. Fidelity to intent requires careful attention to details of the installation and the functioning of the equipment. McQueen had felt that he had “locked down” the specifications for the piece and made it very clear exactly what was to be done. In the course of our discussions, he realized that more could be done. While the specifications for McQueen's installation are really quite simple, it was surprising how much could go wrong given that the artist wanted a high degree of fidelity. Thus more detailed documentation presented in a clear manner and on-site installation oversight are a necessity, especially considering that SFMOMA is a very sophisticated venue for a work of this sort and other potential venues and staff expertise will likely vary. 3. What is the artist's intent for conservation (for those artists present), and how is this determined in the absence of the artist? Like many artists, McQueen had assumed that many preservation issues were self-evident, and he had not anticipated the issues or difficulties that arose. Artists are rarely involved in this sort of discussion about their work and are often taken by surprise. Bill Viola (b. 1951) had to deal with these issues on the occasion of a survey of his work (Viola 1999), but his experience is not typical. In the absence of the artist, documentation must be relied on to explain the artist's intent for conservation (Roosa 1998), and it is not always readily comprehensible. We asked Steve McQueen whether there were any inherent qualities to the video projector that he found aesthetic. I posed this question: If it were possible to substitute a high-density and very high-quality image and a very small piece of equipment in the future for the existing technical configuration, would this somehow compromise the aesthetic of the work? McQueen had no objection to such a substitution and was not attached to the characteristics of the video projector. He felt that the limitation was the quality of the video or the film it was copied from and that the closer the fidelity to the original film, the better. 4. Where is the “heart” of the work? (i.e., what are the essential aesthetic and technological elements that absolutely need to be preserved if the piece is to retain any integrity into the future?) The “heart” of Deadpan is a sequence of visual images that should proceed at a certain pace in a space carefully designed for them to take place in. Clearly, there is a “story” or narrative, but it must take place within an exact three-dimensional space that can be characterized in detail. It can also be characterized in terms of its visual qualities—i.e., it must be in black-and-white and not have any elements of color entering into it (such as the blue flash briefly introduced when the settings on the video projector were set incorrectly, mentioned earlier). A certain degree of brightness must be maintained that could be compromised by dirty walls or poorly performing equipment. In the case of Deadpan, there are no sound levels to maintain, but sound entering from outside should be kept to levels that constitute nonintrusive background noise. 5. How does the conservator determine what components will need preventive conservation? In the case of Deadpan, the equipment, such as the video projector, simply facilitates the work and is not a part of it. The laser discs contain the actual content but are derived from masters, which in turn are copied from the original films. Maintenance and preservation of this material have been addressed elsewhere (Roosa 1998). Unlike traditional art forms, works like Deadpan are plugged in and experience a kind of acceleration of the law of thermodynamics compared to traditional art forms. Accordingly, Roosa (1998) has suggested that preventive conservation should be emphasized through regular maintenance of equipment, the use of surge protectors, and so on. In short, when economically feasible, anywhere a preventive approach can be applied it should be applied. 6. When does intervention change the work of art? (i.e., remastering of a videotape to laser disc or replacing a tube television with a chip model) McQueen is not attached to the format and is open to migration to better technology that would be more faithful to the original film. McQueen has no aesthetic attachment to the video projector. 2.2 EIJA-LIISA AHTILA'S ANNE, AKI AND GODAnne, Aki and God involves an installation described as follows in the exhibition catalog: It should also be pointed out that the actress chosen to play “Anne Nyberg” was present in the Kiasma, Helsinki, exhibition and at the Grasser and Grunert installation in New York (Reinola 2000). The actress sat in the chair and answered audience questions. It was not possible to have the actress present in all the installations.

Eija-Liisa Ahtila was not present at the TechArchaeology Symposium, but the curator of Seeing Time, Robert Riley, was available to discuss the work. One of the monitors was removed from the show because of technical problems. Apparently one of the seven DV discs did not work and could not be repaired before the opening. It seems the problem could not be resolved, and the monitor was pulled from the show (Reinola 2000). When informed of the problem, Ahtila expressed concern and was disturbed to learn it was not resolved and the monitor not replaced. Once again, we will examine the discussion questions in regard to the piece. 1. What types of procedures are most effective when examining the work? This is a fairly complex installation that involves the fabrication and assemblage of virtually all the components of the installation. Seven submasters were provided by the artist to serve as collection archive masters. The issues described for McQueen's piece (see sec. 2.1) also hold true, with the added complication of caring for the props (see appendix 1) as if they were museum objects, at least during the installation. During the exhibition the installation appears to be a kind of decorative arts gallery. Once again, highly detailed documentation could be used to record and monitor the room's physical characteristics, light levels, and sound levels. These could all be examined and monitored on a regular basis. In works such as Anne, Aki and God, for which props are fabricated or bought in stores, the museum faces a dilemma. If the items are treated as disposables, an unclear message is sent to museum visitors, who may not be able to readily understand why the props are not art but exhibit pieces, while in other areas of the museum pieces that may look the same to them are art and cannot be touched, handled, or sat upon. However, treating props made for the show or furniture bought for the show as art objects—accessioning them as part of the installation and maintaining them in accordance with that status—presents other problems. Gathering and construction of props are laborious, and there is a strong temptation to keep this material or ship it for other installations when possible. Similarly, the electronic equipment is specified but not provided. As mentioned before, even though these pieces are not classified as actual art, they should be examined regularly, cleaned, and adjusted, and the state of the hardware should be assessed for degradation (Roosa 1998, 43). 2. What is essential to determining origins and authenticity of the work? For Anne, Aki and God, the artist has a very definite spatial arrangement in mind and specific ideas 3. What is the artist's intent for conservation (for those artists present), and how is this determined in the absence of the artist? Viola's approach is to require a careful and very thorough documentation of the installation and of maintenance procedures, with explicit statements regarding the artist's desires in regard to these issues (Viola 1999). Ahtila recommends the same approach, and she is in fact striving for more careful documentation and a greater degree of involvement with each installation and is working with a technician on her installations (Reinola 2000). However, a concern for the artist was a loss of control after the installation was completed, when the museum must take over maintenance. In the absence of the artist, the museum or collector has to make the best choices when dealing with conservation concerns, such as equipment failure, as they arise during the exhibition. The choices are, of course, based on their understanding of the artist's wishes, and the museum's or collector's ability to carry out these instructions. 4. Where is the “heart” of the work? (i. e., what are the essential aesthetic and technological elements that absolutely need to be preserved if the piece is to retain any integrity into the future?) As with Deadpan, Anne, Aki and God is a narrative, or in this case seven, or possibly more, visual and audio narratives taking place in a carefully defined environment. This abstract, ideal, or Platonic conception of the piece is the heart of the work, and a faithful physical manifestation is the form it should take. A computer model could be constructed that would include textures and lighting and stream the video through virtual monitors, but it would still not enable the viewer to actually experience the space. The computer model might be useful as documentation of the work but would in itself present problems of preservation, conservation, migrating media formats, and technological platforms. Works such as Anne, Aki and God or Deadpan challenge the conservation profession because they are not simply material objects but also involve the energy source to power the machines that makes the narrative unwind in a repeating one-hour loop, so they also have a temporal aspect as well as a physical one. It is quite possible that in the future, recreating this installation may involve emulation of the power source as well as the technology. It has become impossible to anticipate technical evolution over even relatively short periods of time. Accordingly, I think we have to think of the “heart” of the work as a portfolio of intellectual descriptions in various forms— text, graphic, and audio documentation—and hope that these will be migrated into viable formats that will enable people to recreate the installation in the future in a form the artist would recognize and accept. 5. How does the conservator determine what components will need preventive conservation? For Ahtila's piece, the only things provided by the artist other than information are the seven submasters used to serve as archive masters. These need to be |