THE FIRE AT THE ROYAL SASKATCHEWAN MUSEUM, PART 1: SALVAGE, INITIAL RESPONSE, AND THE IMPLICATIONS FOR DISASTER PLANNINGSARAH SPAFFORD-RICCI, & FIONA GRAHAM

1 1. INTRODUCTIONOf the many disasters that can strike a museum, a fire is among the most destructive. In Canada, there were at least 27 museum fires between 1970 and 1990. The 1990 fire at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum was one of the most severe (Baril 1990). 1.1 1.1 THE MUSEUMThe Royal Saskatchewan Museum (RSM) is the provincial museum of Saskatchewan located in Regina, Canada (fig. 1). The museum dates back to 1906, and the collection mandate includes First Nations (native Indian) objects, natural history material, paleontology materials, and some local history objects. The museum has occupied its 51,000 sq. ft. building since 1955. The building is of simple design, with a center block for the lobby, gift shop, and administrative offices. The center block is flanked by two wings: one wing consists of two levels devoted to exhibition galleries; the second wing houses, on the main level, an auditorium and boardroom, and, on the lower level, natural history storage rooms and museum education areas. The remaining storage areas and staff offices for curatorial, conservation, and exhibit personnel are in a building across the street, referred to as the Museum Annex. At the time of the fire, there were 40 staff members, including 3 conservators, at the RSM.

In the late 1980s, the museum began the considerable task of updating all the exhibits in the gallery wing. The original exhibits, constructed during the 1950s, consisted of long aisles flanked by dioramas and display cases. The new galleries were designed in a winding layout with objects and didactic materials in exhibit cases, in open and sealed dioramas, and on pedestals. By 1990, the museum had opened an Earth Sciences Gallery on the lower level and was in the midst of construction for a First Nations Gallery, also on the lower level. The Life Sciences Gallery on the upper level was next in line for renovation. 1.2 1.2 THE FIREThe fire occurred on Friday, February 16, 1990, in the partially finished First Nations Gallery, lending support to an adage in conservation that fires occur most often during construction. The first large display in the gallery was a replica of a rock wall (15 � 20 � 2 ft.) constructed of polyester resin and fiberglass and decorated on the wall face with pictographs. An outside contractor had been brought in to inject a typical two-part polyurethane foam insulation behind the wall to add strength to the structure. After the contractor and a museum technician left the building for the evening, a fire began in the gallery. Although no official cause of the fire was ever determined, the fire was presumed to have started when the insulation foam self-ignited. Heat had begun to build up due to the exothermic reaction of the two-part foam, which was sandwiched between the resin and fiberglass rock wall and the fire separation gallery wall. The foam, and eventually the materials surrounding it, proceeded to burn until an ionization smoke detector in the central return air duct registered the presence of smoke and triggered an alarm connected by a radio link to the fire station. The alarm sounded at 10:26 p.m. Six units and 14 firefighters arrived at the rear of the building within two minutes. Looking through the windows, they could see no evidence of fire. Then, only seconds later, thick billows of smoke appeared. Immediately the firefighters broke through the windows to enter the smoke-filled lobby. Because of the incredible speed of the black smoke buildup, in combination with several other factors, the firefighters conducted an hour-long search of the building before they were able to locate the source and extinguish the fire (Usherwood 1991). The fire completely gutted the 900 sq. ft. area represented by the room that held the rock wall but was mostly contained within it, and only 1,000 gal. of water were used in the firefighting effort. While modern construction materials in the gallery prevented the flames from spreading and protected the structure of the building from serious damage, the smoke produced from the smoldering hour-long fire spread throughout the museum, depositing soot on every surface. The smoke traveled down aisles and stairs and was circulated to every corner of the building by the museum's highly efficient fan system, which had failed to shut down. The rapid and intricate spread of this thick, black, sticky smoke proved to be the greatest tragedy of all. The museum had no disaster plan and was caught completely off-guard. In the First Nations Gallery, where the fire had started, the contents of the room—drywall, the rock wall and insulation, the partially constructed diorama, and exhibit supplies—were almost fully incinerated. Metal ducts and construction equipment were deformed by the intense heat (fig. 2). The products of incineration—i.e., the airborne soot—filled the First Nations Gallery, where the white, freshly plastered curving walls and empty cases were now covered with a thick layer of soot. The lower half of the walls had turned from white to gray, and the upper portion had blackened from the accumulation of the soot-filled air near the ceiling (fig. 3). The soot took on a different appearance depending upon its distance from the fire: in the immediate area of the burn site, the soot on the walls formed weblike filaments up to an inch long (fig. 4); in the galleries farther from the burn site, soot covered the surfaces with a black powdery mat (fig. 5).

Smoke generated by the smoldering fire followed the predominant air current through the First Nations Gallery and then up through ducts—left open during the construction—into a Life Sciences Gallery located on the floor above. This gallery was covered with a very thick soot layer (see fig. 5). The exhibits contained birds and animals on natural foregrounds in dioramas. The diorama shells, which were composed of acrylic paint on plastered forms or commercial tempera paint on primed canvas marouflaged to drywall, were pushed tight but not sealed to glass fronts. The fine soot easily penetrated this small air space, depositing in such an even fashion that the full extent of damage was not always apparent until a portion of the area was cleaned to provide a comparison (fig. 6).

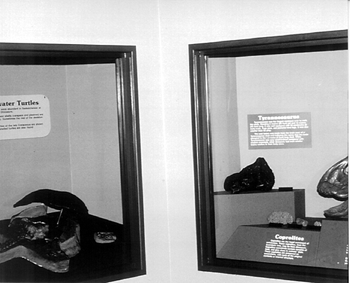

The fire separation wall and a temporary construction door at the burn site had prevented the fire from penetrating the neighboring Earth Sciences Gallery. In this gallery the soot deposition was somewhat less than in the gallery on the upper level since it was naturally at a slightly lower pressure. Moreover, the doors to the Earth Sciences Gallery had remained closed for most of the fire, and the smoke had a tendency to rise rather than move laterally. However, some soot did travel through the ventilation system and also through the temporary construction doorway separating the First Nations and the Earth Sciences Galleries when it was opened during the fire search. A thicker mass of smoke traveled above the suspended ceiling tiles, which bulged with black soot. A replica of a turtle skeleton, enclosed in a display case, was blackened from soot dropping down through a quarter-sized hole made for lighting the case (fig. 7).

Bird specimens, stored in closed but not sealed wooden cabinets on the lower level, farthest from the burn site, did not escape without harm. Soot entered the cabinets through minute gaps, leaving a light dusting on the approximately 1,500 mounted specimens (fig. 8). A similar deposition was left on the mammal mounts and furs stored on open shelving in another room that had been opened during the fire search. In the administration areas on the third level, soot penetrated behind closed office doors, between papers in closed filing cabinets, in desk drawers, cabinets, storage boxes, and through all other imaginable crevices.

The degree of soot coverage varied throughout the building. It was apparent that the thickest soot coverage occurred on the upper floors and in spaces that allowed free passage of soot down aisles, through open ducts, and above ceilings. Soot deposition was less in areas with closed doors, negative air pressure, and little ventilation (particularly since the ventilation system had failed to shut down). There was also less soot penetration in rooms that were not opened during the fire search. The only portions of the building resistant to the penetration of soot were the walk-in freezer and fully sealed units such as display cases with windowed fronts sealed with gaskets. |