CORCORAN AND CODY: THE TWO VERSIONS OF THE LAST OF THE BUFFALODARE MYERS HARTWELL, & HELEN MAR PARKIN

4 TREATMENTToday, the most dramatic compositional difference between the paintings is the absence in the Cody version of a 10 1/4 in. � 8 7/8 in. area (26 � 22.5 cm) at left center, removed at some point in the past. The large standing buffalo at left, seen in the Corcoran painting turning toward the viewer and eyeing the mounted figure at right, is missing in the Cody painting, replaced by a canvas insert that has a much smoother surface texture (fig. 11). The reason for this violent intrusion upon the artist's intention is not clear.

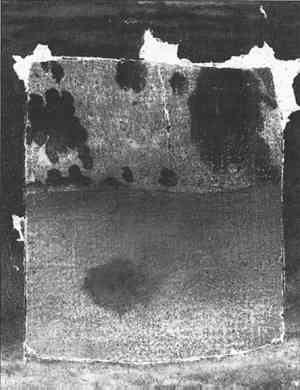

During the treatment of the Cody painting, this missing buffalo presented a challenging inpainting problem. Peter Hassrick, director of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, had expressed a wish that the insert not be removed and that its outline be left visible under certain viewing conditions to document the actual extent of original design and the history of the treatment of the painting. The removal of repaint in this area revealed that the insert had been cut from another painting and depicted part of a crudely painted brown-and-white cow. It had been glued in upside down, then repainted to blend with the surrounding landscape (fig. 12). Upon close inspection, traces (the reddish brown tip of the hump and the long shadows below the hooves) of the buffalo that had originally occupied the space were

Before inpainting could be carried out, however, it was necessary to adjust the surface texture in the insert area so that it would be less noticeable to the viewer. The painting was first given a brush coat of Soluvar Gloss varnish (a proprietary acrylic resin, probably an n-butyl methacrylate/n-butyl acrylate copolymer, made by Binney and Smith for Liquitex). When the varnish had dried completely, an impression was taken of the surface adjacent to the insert area, using a two-part silicone rubber mold material first used by Gregory A. Thomas, painting conservator, to take surface impressions of paintings (Dow Corning RTV 3110). To take the impression, a 1/8 in. (.3 cm) deep dam, slightly larger than the insert, was constructed using strips of four-ply mat board. The liquid mold material was then troweled carefully into the area and smoothed until it entirely filled the dam. It was allowed to cure overnight, after which the finished mold was peeled slowly away from the painting, resulting in a detailed negative reproduction of the surface texture. The mold was placed face up on a large hot plate and warmed to approximately 200�F. Molten microcrystalline wax (Bareco Victory White, melting point 165�F) was brushed thinly onto the mold. Meanwhile, the area of the insert was warmed with an incandescent light held close to the surface, while the surrounding area of the painting was protected from overheating by strips of aluminum foil. The warm, waxed mold was then turned face down onto the area of the insert and pressed into place, using the fingertips, for several minutes until the wax cooled. The mold was then peeled away slowly. The thin wax layer remained on the surface of the painting, transferring the texture to the insert area. The edges of the waxed area were then textured locally with a dental tool to blend with surrounding areas, thereby softening the transition line. A 35mm color slide of the corresponding area on the Corcoran painting was projected onto the textured area and adjusted until it lined up precisely with the remaining original clues of the hump and shadows below the hooves. (In fact, because of the preciseness of this fit, it is tempting to speculate that Bierstadt may originally have used lantern slides to transfer some of the composition elements from the Cody to the Corcoran painting.) The outline of the buffalo was then drawn, and the inpainting was completed using dry pigments ground in poly(vinyl acetate) AYAC (Union Carbide). An 8 � 10-in. (20.3 � 25.4) color transparency of the Corcoran buffalo and a steel plate engraving made after the Corcoran painting were used for reference in the reconstruction. By reintegrating this important design element into the Buffalo Bill Historical Center's Last of the Buffalo, the painting has been returned more closely to Bierstadt's original intention. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe authors would like to express their appreciation to both the Corcoran Gallery of Art and the Buffalo Bill Historical Center for the support of their research, and in particular wish to thank Perry Huston, Nancy Anderson, Franklin Kelly, and the staff of the Scientific Research Department at the National Gallery of Art who carried out the technical analysis of both paintings. |