REFLECTIONS ON PAINTING, ALCHEMY, NAZISM: VISITING WITH ANSELM KIEFERALBERT P. ALBANO

ABSTRACT—Salient aspects of the artwork of Anselm Kiefer are reported and discussed based on the artist's expressed artistic intentions, social concerns, and technique and use of materials for the fabrication of artworks. Many of the sources for the art's thematic content are identified and described by the artist. The significance of this information is contextualized in light of the artwork's physical makeup and its relationship to long-term preservation. TITRE—R�flections sur la peinture, l'alchimie, le nazisme: un regard sur Anselm Kiefer.R�SUM�—Des aspects caract�ristique de l'oeuvre d'Anselm Kiefer sont pr�sent�s et discut�s en rapport avec les intentions artistiques et les pr�occupations sociales exprim�es par l'artiste, ainsi qu'avec ses techniques et l'utilisation qu'il fait des mat�riaux n�cessaires � la fabrication des oeuvres. L'artiste a identifi� et d�crit plusieurs sources � la base du contenu th�matique de ses oeuvres. L'importance de cette information est mise en contexte et �tudi�e � la lumi�re des constituantes mat�rielles des oeuvres et de leur pr�servation � long terme. TITULO—Reflexiones sobre pintura, alquimia y nazismo: una visita a Anselm Kieffer.RESUMEN—Aspectos sobresalientes del trabajo art�stico de Anselm Kieffer son relatados y discutidos bas�ndose en las intenciones art'sticas expresadas por el artista, su preocupaci�n social, y su t�cnica y uso de materiales para la fabricaci�n de su obra. Muchas de las fuentes del contenido tem�tico de su arte son identificadas y descritas por el artista. El significado de esta informaci�n es contextualizado a la luz de la composici�n f�sica de la obra y su relaci�n con la preservaci�n a largo plazo de la misma. 1 INTRODUCTIONThroughout the 1980s, Anselm Kiefer (b. 1945) produced an extraordinary body of work that earnestly addressed the dense external and internal conflicts and consequences of German cultural and political history, and matters of the human spirit. Kiefer referred to subjects and areas of German identity that had commonly remained only tangentially expressed in painting. He implied that this phenomenon was fostered by a selective historic memory and by the inclination in contemporary German thought to disassociate from the mid-century experience. Kiefer's paintings and studies persuasively attempted communication with the complacency or anxiety latent in selective memory and with the troubled or spiritually atrophied psyche. As this work explored the complex scope of Kiefer's and Germany's collective cultural and historic identity, it focused on the multiple messages and interpretations of history and on the personal concerns of the spirit. The work still retains much of its conscious ambiguity about the past and the artist's personal relationship to it, while providing sufficient references and symbols to generate a growing body of analysis and interpretation; yet, definitive judgments about its intent may continue to remain elusive. With the social turmoil and its associated anxieties in postunification Germany, Kiefer's paintings continue to sustain their relevancy and interest. His work may well be more temporally poignant than when I visited with him in the mid-1980s while I was working for the Museum of Modern Art, for events in Europe in the intervening years have magnified some of his themes. Always relevant are his insights concerning matters of the spirit and their role in art and life, which he has identified in his work and through his process of creating a painting. Particularly revealing to his intent are his perspectives about change and physical evolution in his artwork.1 It is illuminating to revisit the Kiefer of the 1980s before his Wagnerian G�tterdammerung performance of May 1, 1993, as chronicled by art critic Jerry Saltz (1993). This “neo-Baroque” evening performance and Kiefer's last solo exhibition of 1991, during which remaining portions of his oeuvre representing the residue of his fertile 1980s work were to be symbolically destroyed in an art-mound bonfire, may have represented the nadir of his career and the termination of many of his preoccupations of the 1980s. A fallow period followed. He resumed producing paintings in 1995, following a personal transition that included a relocation of his studio from Buchen, Germany, to southern France and a jettisoning of much of his previous environment and historical thematic sources. 2 THE VISITWhen I set out from modern Germany and descended inward, reaching the small village of Buchen huddled in the midst of the Oden Forest, arriving finally at the workplace of Anselm Kiefer, an isolated hangarlike structure in a field, I felt that somewhat of a metamorphosis had occurred. This journey, however, was only the prelude to what awaited there. I embarked on what would be a more challenging journey as the opening door revealed the private domain of Kiefer's farreaching artistic vision and expansive thought process. Kiefer met me with a nearly immediate suggestion to explore his studio without him and view a forest of paintings and sculpture in all stages of progress (fig. 1). This was an inducement to be transfixed, as it would have been difficult to resist succumbing to what I saw and discovered. Kiefer appeared soon after and assured me quite ingenuously that he believed his art would not, or could not, change anything in this world. At that instant, I understandably did not believe him, for the impressions of what I had just seen dominated my sensibilities. In spite of Kiefer's sobering declaration, I felt about his paintings as William Carlos Williams did about poetry: “It is difficult to get the news from poems, but men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there” (Williams 1988, 2:318). Kiefer's work showed a visionary ambition so broad as to call to mind a parallel to Wagner's Ring Cycle. However, Kiefer did not appreciate the comparison because he found the composer to be an ugly man overrun with petty prejudices who could rise above these only through the vocal beauty in his music.

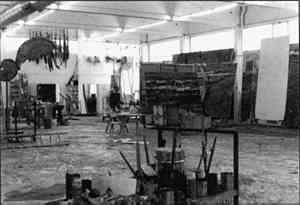

Kiefer made a point of stressing that he did not like to be quoted and found it more interesting to read what others bring to his work. Kiefer initiated conversation by introducing his art in the studio and warning me that only two of all the pictures I was seeing were close to being finished (fig. 2). He wheeled away a large work in progress to reveal the painting on which he was then working. It was a massive image of breaking ocean waves with a large lead sculpture of an open book suspended from its center, Das Buch (1979–85), now in the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution. He began to talk about his interest in the ocean as a source of continual regeneration and, pointing to the horizontal lines forming the repeating shapes of undulating waves, said that the turning of the leaves of a big book were like the shape and movement of crashing waves. He liked the idea of these books representing large medieval incunabula.

“Working itself, for me, is not the hardest part of being an artist, but deciding when the image is complete or knowing when it holds the intent you want is the most difficult and strenuous,” Kiefer explained. He worked on pictures over many years. At my visit, some uncompleted paintings had been with him for as many as 12 years. He explained that he worked only on the painting he felt intuitively drawn to at that moment. “My mind,” he said, “is like a million persons filled with different thoughts and feelings, and in the process of trying to create something you lose one of those people and the associated feelings and thoughts when the work is finished.” All of his ideas were from things he had seen, felt, or known throughout his life. He gave me, as an example, the portions of remembered school-boy poems or stories that he has used in his paintings, such as the verses from Victor Hugo's “Waterloo” or the story of the first-century Roman general, Varus, whose legions were destroyed by a Germanic tribe. Kiefer took thousands of photographs, as readily confirmed by the hundreds that were strewn over the studio floor and numerous work surfaces (fig. 3). He tried to have all of these images readily accessible when he was working and selected whichever image he intuitively related to the painting on which he was engaged. Images and materials often began to fill the space of the entire studio, and

I asked Kiefer why he had changed the lead staff in the painting Departure from Egypt (1984), first exhibited in the Marian goodman Gallery in New York and later bought by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. I had seen that the lead staff suspended from the painting was clearly changed from the photo-reproduction on the gallery announcement. He explained that, while he wanted to include recognizable images in his work, often they become a problem if they start to dominate the picture. This had occurred with the lead staff, and he altered it. I mentioned another work in progress, one that supported an extremely detailed, large lead jet plane (fig. 4). He had originally planned to use more of the lead planes I saw scattered throughout the studio but ultimately decided they were too naturalistic, although he still liked to keep them as objects in the studio. He made many such objects, and each could have a different or more than one meaning for him at any one time. They took on a more specific meaning according to the painting for which they were used and the way he used them. An example he gave me was his repeated use of a snake as a painted image or fabricated lead form, which he said “represented many things.”

Kiefer pointed out that sometimes there is an obvious meaning in one of his paintings; however, that obvious meaning is usually “little,” and there is commonly a “more important, big meaning” that makes the inherent or potential irony of the work more interesting for him. The example he chose to illustrate this point was his Tomb of the Unknown Painter (1983), wherein the irony for Kiefer is that today the artist is anything but unknown. I asked him what the lead propellers and rocks attached to a nearby work in progress meant for him. The lead

I encouraged Kiefer to talk about his thoughts concerning the act of painting and the specific reasons for his choice of such diverse and often unstable materials as straw and shellacs. He chose materials, he said, that contain and/or would give off energy when they were used (fig. 6). He thought he had first used lead in 1974. I asked whether its use was due to an influence from Joseph Beuys, for Kiefer was one of the last students before Beuys left the Dusseldorf Academy in 1972. Kiefer said that, while he very much liked Beuys's work, his own selection and use of lead was not the same as his teacher's. He had intuitively remembered lead as a material many years after seeing it being turned from one physical state to another. He called it a “marvelous, beautiful material.” He later started using it in his own associative meanings without thinking of Beuys.3 In the process of heating and melting lead, he saw many colors in its transformation from solid to liquid to solid again. He saw the color of gold during this process, not that of metallic gold but the symbolic gold sought by the alchemists.4 He liked the oxidation of white on lead and often tried to induce it artificially with acid in selective areas when he did not want to wait six months or more for the look of the natural lead oxidation.5 He told me that it is an ancient material, represented the planet Saturn, and was associated with the alchemical concept of magic numbers. He remarked that this alchemical concept of numbers association was very complex but emphasized that “twelve, of course, as in the apostles” should be clear.6

I asked about the significance for him of the color transformation process. Kiefer responded by explaining how he translated alchemical concepts into artistic terms and talked particularly about how these concepts affected his choice and use of materials like shellac and straw. His feeling about shellac corresponded to that of lead in terms of the color and energy possibilities. He sometimes mixed it to 10 or more different varieties of yellows and selected the one he intuitively felt was the most appropriate for the picture on which he was working.7 He also used clear shellac on occasion (fig. 7, p. 353). He liked shellac's warmth and glow and its hard, brittle quality, even the cracks that develop as the material transforms and hardens.8 He gave the example of its use by furniture makers as a material that, while it is rubbed and polished, takes on energy and becomes warm to the touch. His relationship with straw resonated a similar associative process (fig. 8, p. 353). “I like straw. I am really a farmer,” he said. “It is a material from the earth which is also golden and gives off energy, heat, and warmth when

I asked Kiefer how he developed his complex painted surfaces and what significance this process and appearance had for him. He said that he built up his canvas surfaces starting with large, thick applications of a black-and-white patchwork of paint on the white ground (fig. 9, p. 354). He continued to add more and more paint and then sometimes applied another whole section of canvas to the surface as a patch. At other times, he applied an entire canvas with large holes to reveal painted portions of canvas beneath it. He liked this technique because it is like the layers of a great mountain, with the torn upper sections revealing different stages of growth below. He also saw these different layers of his paintings as symbolic of different phases of existence. After this detailed description, he added, “Exactly how I do art is not so important, but what I am trying to do is.”

Kiefer continued to describe this process. On one large picture he had tried to use a large portion of molten lead, but had been unable to melt and pour this amount successfully onto the surface of a canvas. As an alternative, he chose to burn that area of the painting to simulate the look of the molten lead. He burned the paint and, ultimately, the canvas from the front while it was being wetted from the back, until the surface and paint were transformed to the colors he wanted. He sometimes applied many layers of color and then burned them darker or covered them with black paint to simulate a burned appearance. He transformed, for example, the color blue to green by heating. He also might pour molten lead over the painted surface and then rip off the whole, intimately combined section of lead and paint. He might use these “comets,” as he called them, to put over photographic images to create small studies. If a large section he had cut out of a painting was interesting, he might incorporate it as needed into into another work in progress or work on it as a separate painting. He considered the works on paper, like the ones shown at the Goodman Gallery, New York, in 1985, studies I asked if there was any significance to the large sizes of his paintings. He said the largest size he was then working with was the size of his original studio's wall and the biggest he could do at the time. If he wanted something bigger, he would put paintings together so they could be separated and folded. I mentioned the weight problem of his big pictures with lead appendages attached to the front and their sagging canvases leaning on the stretcher. He told me the stretchers were made in the local village and that anything more solid that covered the back would interfere with his cooling of the canvas when he was burning the surface. We talked further about some of the practical problems his technique presented. I described problems with the stapled-on lead strips in The Red Sea (1984–85), owned by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. He answered that these lead strips forming a rectangle over the bathtub represent a higher or next spiritual level or stage and that the vertical strips are like lightning connecting this above stage to the stage below. He stapled on the lead and put the wood behind it to hold the lead in place, knowing this support was not adequate. He stressed that his process was so spontaneous that he could not plan it out ahead of time by, for instance, building supports on the back of the canvas. When I told him that collectors, dealers, and curators had voiced concern about the stability of his pictures as a consequence of this spontaneity, he said it was silly for people to worry about his pictures changing. Change was part of the process, and their meaning or content would not be essentially Kiefer ended this topic by repeating that he wanted to imply a spiritual meaning to all of these materials we had discussed, meanings that he believed had been lost during the 19th and 20th centuries. He said, “It was like man's use of technology being all quantitative and not qualitative, like the computer. It could do more than man could understand, faster, but it was only horizontal speed. Man' life should be vertical, so that his life would and should exist on many planes. Man could travel in space as fast as he could and go very far, but this was only quantitative. He must elevate himself vertically to different levels, and, until he achieved this, he would not be whole.” Kiefer had started to think independently along these lines, and his ideas were further reinforced, after he had gone to Israel, by his reading of Gershom Scholem's study of the Kabbalah.10 Following this trip, Kiefer began to incorporate some of these concepts concerning different vertical levels into his work by constructing a whole series of objects that he considered his private work and not for public view. He showed me some of these in a smaller room of his studio. I saw other work utilizing these concepts at a second studio. Here, in the middle of the floor, was a forest scene made with dried, fernlike branches. Over this were three 24-in. square pieces of acrylic sheet held at the corners with thin filament, hanging in succession one above the other, slightly tilting at different angles, with large melted puddles of lead lying on them and dripping down over the edges. He believed that most of the people who know of or have read mystical texts like the Kabbalah do not or have not seemed to understand the unconscious significance they offered. “They Kiefer spoke of his work very protectively and reiterated that he did not like giving his pictures out. He stressed that he controlled the distribution of his work. He thought he would keep some of his best pictures or buy some of them back and “when I'm in my sixties, I'll give them to museums.” That is why, he said, he gave out as little work as possible. I then mentioned that, perhaps, museums are the storehouses for the bones of art. He liked this thought and laughed a good deal about it. It reminded him, he said, about the monks he had met in Israel who showed him a coffin filled with bones and told him they were trying to find out which were the bones of saints and which were those of ordinary people. The monks assured him that they would, someday in the future, be able to do so. While he had been raised a Catholic, he thought that Christ was only one of many prophets at the time, although he believed that Jesus believed himself to be the Messiah. I asked Kiefer about the numerous variations of winged palette sculptures then in his studio and what interested him about their imagery (fig. 10, p. 355). He said that the idea of soaring or the image of flying used so much in Johann Goethe's Faust depicted the spiritual sense he wanted to portray in these works. He said that the idea is sometimes antiheroic, like the lead wings of the sculptures he was then making with palettes or books. He said, “The feathers go down. They are a little bit sad, I think.” He talked then of Leonardo da Vinci's dreams of flight and his failed inventions attempting flight. These, he thought, relied on a limited technology as Leonardo could understand it in his own time. Leonardo had a spiritual desire, but he could not transcend his belief in the ability of his limited machines to accomplish his spiritual inspiration. When I asked Kiefer further about his meaning in the Leonardo reflections, he said that “people remembered all of the events in history only linearly and can only see from the vantage point of the present looking back or projecting forward.” He remembered a reference from Friedrich Nietzsche and said, “But they cannot see themselves in the present and interpret what any of these events have meant.” Kiefer also saw the lead wings on palettes as being like pulpits. I had previously noted in his studio many photocopies from books of 16th- and 17th-century pulpits of all types. These were cluttered with those of gallows from concentration camps, which, when I asked, he told me he would not use because they would be too literal for him in his work.

Kiefer had begun buying books on German history during the 1960s, and he said that now he was finished with the Nazis. He added that when he had photographed himself with the heil salute he had done so intuitively and involuntarily, almost mechanically, and did not think about it until after. These artworks had been badly interpreted and misunderstood by many who had not comprehended the irony; he was deeply troubled at being called a Nazi for so long by people who did not understand what he was doing with his art. He said that Nazism's idea of permanence was an illusion. He recounted to me an anecdote he remembered about an artist who told Adolf Hitler that he had invented a permanent ground and canvas, but that eventually, like the Reich, it started to fall apart. He thought Albert Speer was Hitler's alter ego. Hitler Kiefer said that the program The Holocaust (a sensation on both American and German television) had had a big effect on the German mind, but he thought that it was basically kitsch that, to a degree, is “what the average German likes.” The art of the Nazis should not have been shown in Germany, for it was certainly not art at all, and exhibiting it gave it a spurious legitimacy like the recognition of the architecture of the period, particularly that of Speer. Hitler, Kiefer continued, wanted all buildings made of stone so they would become inextinguishable ruins in history. That was part of what Kiefer saw in his paintings of architectural ruins of Fascist classical buildings. He wanted to show the irony of the comparison of Hitler, desirous to be an artist-architect like Speer and planning for such permanence, with the Germans rebuilding Germany as fast as they could after the war and obliterating the ruins of those same buildings so that there are hardly any left to remind them of their past. He saw further contradiction within Germans in their wish to forget the war while their behavior is still based upon the lingering attitudes that contributed to it. He told me that “even General Erwin Rommel's son is the current mayor of Stuttgart and is very popular.” He mentioned his use of bathtubs to allude to this, telling me of the Nazi promise of one in every house. He said that earlier they used to be easier to find when people threw them out. He showed me the first tub he had found on the roof of the house in which he had once lived. He liked ruins and particularly liked the ruins in Pittsburgh of the old, large coal factories, which he had seen on his trip to the Carnegie Museum of Art. Germany, Kiefer said, was divided in half, not the two physical Germanies, but the Germans of order and structure and those who try to react against it. “Germans overreact to any sign of disorder or threats to their bourgeois lifestyle.” The Jew in Germany had given it a different and more varied personality, he thought, for Jews were intelligent thinkers and made Germany have other considerations about itself. Now that all the Jews have been wiped out of Germany, the German people have lost their cultural diversity, and it is easier for the country to think monolithically. He thought that in ways blacks in America were like the Jews in Germany before they were all killed in the war. He said that the prevalent Turkish labor force in Germany was, to a degree, being subjected to prejudices similar to those suffered by the Jews. “The Germans were more efficient at extermination, that's what made them so much better Fascists.” Kiefer also felt that there is too much disorder in America. He ultimately spoke in very ironic terms about the German sense of order. As the long day turned to evening, I had to alert Kiefer to the lateness of the hour and my concern for my scheduled train departure. He sped us confidently through the forest and rain, along treacherously winding, unlit roads until we reached the tiny, isolated station. We arrived at the station less than 10 seconds before the scheduled arrival of the last train to Frankfurt. He rushed along with an efficiency of movement, grabbing my bag and running out to the train platform with me following. He smiled as the train pulled up and said, “See, they are always on time.” 3 CONCLUSIONSKiefer had said after several hours of our This was clearly a suitable anecdote for Kiefer, whose own attitude and sensibilities on the matter resembled in many regards those of Beuys. Those responsible for the stewardship of Kiefer's work, who are alarmingly concerned about its physical alteration, need to consider his compelling motives and vision for what he creates. Too narrow an interpretation of the implications of physical alteration in Kiefer's artworks significantly limits their breadth of communication. Kiefer's stated artistic intentions, encompassing a charged and dynamic view of materiality, history, and spirituality, will not, he believes, be substantially diminished by this aging process.12 His art's altered appearance will, in a sense, influence the future context in which it will be understood. Concomitantly, future viewers will bring both modified opinions of these issues and entirely new criteria to the art's interpretation. If Kiefer's work is understood and accepted as art evolving physically and, then, visually with the advance of time, his audience will perceive one of its many significant components. All art can only be preserved for a parametrical perpetuity, not for an unrealizable eternity. Kiefer's art will endure these dynamic variables, as he anticipates and intends, in contradiction to those who might predict its premature physical demise. As Marcel Duchamp said, “Men are mortal, pictures too” (quoted in Cabanne [1967] 1987, 67). NOTES1. Kiefer's perspectives concerning his choice of materials and the fabrication and alteration of his artwork were communicated to me primarily during two meetings with him, one occurring at his studio in Buchen, Germany on October 5, 1985, and the second on October 11, 1985, at the German Expressionist exhibition held at the Royal Academy in London. As of February 1993, the time of my last request to Kiefer for any additional information or altered perspectives on any material previously communicated to me, he chose not to offer any new insight with the knowledge that his position was eventually to be published. 2. Jung suggests that the principal ideas of philosophical alchemy were shared and freely discussed by the Gnostics, whose analogical thinking is akin to that of the alchemists (Jung [1953] 1967, 147). In alchemy, the spinning wheel is a favorite symbol for the circulating process. The mystical associations for the wheel or its contemporary moral allegories are many. One key interpretation in alchemy, shared by the Gnostics, is that of the circulatio or the ascensus and descensus, which are associated with the moral allegory of God's descent to man and man's ascent to God, or thus are a concept for wholeness (Jung [1953] 1968, 164–66). 3. The concept of the prima materia within the alchemical hierarchy is of singular significance, if not of singular definition. It did, however, carry for the individual alchemist the “projection of the autonomous psychic content.” Of the various substances identified by individual alchemists as the prima materia, lead was one (Jung [1953] 1968, 317–20). Its importance in this respect can be traced back to the Egyptians, who called lead the mother of metals. In the sixth century, Olympiodorus codified the association of metals as they were then understood to the sun and planets, as such restricting their number to seven. Within this hierarchy lead became linked to Saturn (Stillman [1924] 1960, 5–9). 4. Symbolic gold is a key concept in the alchemical process, which is commonly acknowledged in chemical transformation. In this process, four stages are generally distinguished: melanosis (blackening), leukosis (whitening), xanthosis (yellowing), and iosis (reddening). The initial stage in this transformation process is the nigredo or blackness (Jung [1953] 1968, 228–29). The alchemist was using the chemical process only symbolically. The gold that he sought was not ordinary gold, as many alchemical books freely acknowledged, but the “philosophical gold” or the “marvelous stone” or other names suggestive of a more complex objective. Their conceptions of this goal were frequently ambiguous and inconsistent. In fact, Jung ([1953] 1968, 232–43) suggests that a key reward, if not an objective, was a “satisfaction born of the enterprise, the excitement of the adventure.” 5. Kiefer did not appear to have any concern for the issues surrounding the toxicity of lead, either associated with its use or with the handling and exhibition of those artworks in which he utilized lead as a major component. 6. The alchemical concepts associated with numbers mysticism are often diverse and complex. However, according to most modern interpretations, two basic principles are the concept of unity within a Trinitarian character in Christian alchemy and a quaternity character in pagan alchemy, thus a spiritual interpretation or a physical one associated with the ancient concept of the four elements (Jung [1953] 1968, 26–27). Some of the other numbers that held varying associative meanings were 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, etc. It is significant to note that of the varying interpretations of the number 12, one of which is the 12 stages or operations in the course of the alchemical process of material transformation, Kiefer chose that associated with the apostles (Jung [1953] 1968, 212). 7. There are recipes associated with material transmutation attributed to one Democritus (by most accounts not the philosopher Democritus who enunciated the first atomic theory), which describe the coloring of metals to imitate gold or silver by colored mixtures, varnishes, or stains to be superficially applied to give a surface resemblance to gold (Stillman [1924] 1960, 152–53). Again, the yellowing process (xanthosis) is one of the four key stages of the alchemical process for the transmutation of the prima materia. In the 15th and 16th centuries the four-color process was reduced to three, with the xanthosis generally falling into disuse (229). 8. Kiefer was far more interested in discussing the choice and use of a toned shellac for a particular painting on which he was working than receiving the information that the aesthetic results would not likely remain permanent because of the shellac's alteration over time. 9. The back of the canvas in a Kiefer painting graphically outlines some of his working methods. This result, in light of his aesthetic intentions as he has expressed them, is purely 10. As Kabbalah evolved there arose a complex hierarchy of a series of worlds from above to below, which became fully codified in the 16th century. This unified doctrine established four primary worlds. The concept, incorporating Jewish, Aristotelian, and Neoplatonic principles, crystallizes each stage of the process of creation within a separate stage or level. Each stage is a perfect expression of one of the many aspects of the creative power achievable by the creator (Scholem 1974, 116–22). 11. Kiefer has accepted the necessity of readhering variously mounted elements of his pictures once they have become loose or dislodged. This has been done when necessary, particularly during the period of the four-venue Kiefer exhibition held between December 1987 and January 1989. Discreet, slight alterations to the mounting of a precariously attached piece of lead or other material component may be necessary to secure it more thoroughly as a consequence of travel requirements. 12. For a further discussion of Kiefer's position concerning his artworks' conservation in relationship to some of the broader issues of contemporary arts' physical alteration, see Albano 1993, 1995–96, 1996. REFERENCESAlbano, A.1993. M�tier perdu, mauvaises mati�res? De la pr�tendue fragilit� des oeuvres d'art contemporain. Annales d'Histoire de l'Art & Arch�ologie(Free University of Brussels)15:7–24. Albano, A.1995–96. Les fluctuations de l'intention cr�atrice et leurs implications en mati�re de conservation. R�cherches Po��tiques(Sorbonne and the University of Valenciennes, France)3(Winter):38–45. Albano, A.1996. Art in transition. In Historical and philosophical issues in the conservation of cultural heritage. ed.N.S.Price, M.K.Talley, and A.M.Vaccaro, Malibu, Calif.: J. Paul Getty Trust. 176–84. Cabanne, Pierre. [1967] 1987. Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, trans. Ron Padgett. Reprint [original Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp]. New York: Da Capo Press.

Jung, C. G. [1953] 1967. Alchemical studies, trans R.F.C. Hull. Vol. 13 of Bollingen series 20, The collected works of C.G. Jung. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Jung, C. G. [1953] 1968. Psychology and alchemy, trans. R.F.C. Hull. 2d ed. Vol. 12 of Bollingen series 20, The collected works of C.G. Jung. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Saltz, J.1993. Swan song 11. Art in America9(September): 45. Scholem, Gershom. 1974. Kabbalah. New York: New American Library. Stillman, J.M. [1924] 1960. The story of alchemy and early chemistry. Reprint [original title The story of early chemistry]. New York: Dover Publications. Williams, W.C.1988. The collected poems of William Carlos Williams, 1939–1962, ed.ChristopherMacGowan. New York: New Directions. FURTHER READINGCarrier, D.1989. Art criticism and its beguiling fictions. Art International9(Winter):36–41. Gibson, E.1988. Reckoning Kiefer. Studio International201(July):22–25. Gilmour, J. C.1988. Original representation and Anselm Kiefer's postmodernism. Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism46(Spring):341–50. Haxthausen, C. W.1991. The world, the book, and Anselm Kiefer. Burlington Magazine133(December):846–51. Huyssen, A.1989. Anselm Kiefer: The terror of history, the temptation of myth. October48(Spring):25–45. Huyssen, A.1992. Kiefer in Berlin. October62(Fall):84–101. Perl, J.1988. A dissent on Kiefer. New Criterion7(December):14–20. Rosenthal, M.1987. Anselm Kiefer. Chicago and Philadelphia: Art Institute of Chicago and Philadelphia Museum of Art. AUTHOR INFORMATIONALBERT P. ALBANO received a B.A. in art history and graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Hofstra University in 1976. He worked as apprentice with Orrin Riley at the Guggenheim Museum before receiving his certificate in postgraduate studies, art conservation, from Cooperstown Graduate Programs and M.A. from New York State University, Oneonta, in 1980. He has held the positions of associate conservator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, senior conservator at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and director of conservation at the Winterthur Museum and Gardens, Delaware. He is currently executive director of the Intermuseum Conservation Association (ICA), Oberlin, Ohio. Address: 8133 Chagrin Rd., Chagrin Falls, Ohio 44023–4743.

Section Index Section Index |