EVIDENCE OF REPLICATION IN A PORTRAIT OF ELEONORA OF TOLEDO BY AGNOLO BRONZINO AND WORKSHOPSERENA URRY

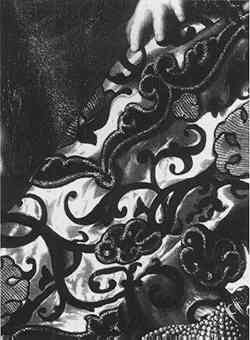

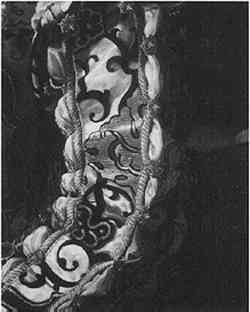

6 QUALITATIVE EVIDENCEDifferences in the quality of the painting are evident when the two portraits are compared. A comparison of the quality of the various hands within the Detroit portrait also proves useful with respect to workshop production. 6.1 QUALITATIVE COMPARISON TO THE UFFIZI PORTRAITThe overall quality of the painting in the Uffizi is superior to that of the Detroit portrait. The difference can be seen even in the handling of the background tones. In spite of the darkened smalt, a certain awkwardness of modulation remains evident in the Detroit portrait. Eleonora's head is surrounded by a U–shaped area of lighter paint. In the Uffizi portrait, the lighter tones of the background fade gracefully off to the sides and behind her figure (see figs. 1, 2). The dress is more believable as a three-dimensional form in the Uffizi portrait, its intricate design securely attached to the undu 6.2 QUALITATIVE COMPARISON WITHIN THE DETROIT PORTRAITMuch of the technical evidence in the Detroit portrait points toward several hands having been involved in its production. It is also evident that these hands were of varying talent. For example, the painter of the background, who may also have painted the landscape, was not particularly attentive. He did not paint the upper portion of the dress, as evidenced by the space he left for the missing linen tag, or Don Giovanni's head, because of the irregularity he left in its contour. The more talented hands in the portrait tend to fall in the visually more important areas of the composition, as would be expected in a workshop production. For example, the clumsiest area of the dress with respect to the handling of the paint is found in the lower left side of the skirt, a relatively unimportant area (fig. 12). The highlights are harsh and virtually illegible with respect to describing the drapery. The small gold-brocaded motifs rest lightly on the fabric, almost as if they could slide off the satin at any moment. The inferior quality of the painting in this area is particularly obvious when it is compared to other, more compositionally prominent, parts of the dress. In Eleonora's proper left sleeve, for example, the highlights in the satin are soft and well placed along the rucked surface of the fabric (fig. 13). The brocaded motif is properly distorted as it undulates. The black design is much more a part of the satin surface. The small linen pouches protruding from underneath are believably rendered in gray and white. The painter of this sleeve was a better artist than the one who painted the lower left skirt.

6.3 QUALITATIVE EVIDENCE OF BRONZINOEvidence that the painter of Eleonora's and Don Giovanni's faces in the Detroit portrait was Agnolo Bronzino is primarily qualitative, though supported by scholarly opinion. As would be expected in a workshop production, the painter of the most important parts of the Detroit portrait, the faces and hands, is superior to all others in the piecework fabrication. The paint has been applied with confidence; no reworking is visible. The lower string of the pearl necklace, painted directly on the finished dress, shows no indication of hesitation on the part of the artist, who at this point was certainly working without an underdrawing. The extreme care with which the other painters kept within the The quality of the painting is characteristic of Bronzino's work. The still expressions are found in most of his formal portraits, as are the off-center gazes which appear to focus on a point behind the viewer. Typical of his technique, paint is built up in thin layers to produce forms of a characteristic impenetrable hardness. Almost imperceptibly applied warm glazes of color and shadow render the forms as polished three-dimensional faces. This luminescent flesh is typical in his portraiture, as is the absence of visible brush strokes. The faces in the Detroit portrait suffer only in direct comparison to the those in the Uffizi original. The Detroit subjects are very slightly less lively. While their quality supports the presence of Bronzino's hand, the somewhat removed effect in their expressions suggests that Bronzino copied Eleonora and her son from the Uffizi portrait rather than painting them from life. This approach would be expected when a replica is being produced. |