EVIDENCE OF REPLICATION IN A PORTRAIT OF ELEONORA OF TOLEDO BY AGNOLO BRONZINO AND WORKSHOPSERENA URRY

ABSTRACT—Portrait of Eleonora of Toledo and Her Son in the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts, attributed to Agnolo Bronzino, was recently cleaned and consolidated. Nearly identical to a portrait by Bronzino in the Uffizi Gallery, the Detroit portrait had long been judged by scholars to be a replica, a copy by the artist. Material, compositional, technical, and qualitative evidence collected during treatment supported, wholly or in part, identification of the Detroit portrait as a contemporary copy of the Uffizi portrait, as the product of a workshop, and as the work of Bronzino himself. Art historical research established replication to be a part of Bronzino's practice. Compositional and qualitative comparisons were conducted between the Uffizi and Detroit portraits. Analysis included x-radiography, x-ray fluorescence, infrared reflectography, visual and cross-sectional analysis, and polarizing light microscopy. TITRE—Portrait d'�l�onore de Tol�de par Agnolo Bronzino et son atelier: Mise en �vidence d'une r�plique. R�SUM�—Un portrait d'�l�onore de Tol�de et de son fils, de la collection du Detroit Institute of Fine Arts et attribu� � Agnolo Bronzino, fut r�cemment nettoy� et consolid�. Presque identique � une autre oeuvre de Bronzino qui se trouve � la Galerie des Offices Uffizi, celle de D�troit a �t� longtemps consid�r�e par les experts comme une r�plique, soit une copie par l'artiste lui-m�me. Lors du traitement, l'information recueillie sur les mat�riaux, la composition, la technique et les analyses qualitatives confirme en grande partie l'identification de l'oeuvre de D�troit comme une copie contemporaine � celle de la Galerie des Offices Uffizi, comme une oeuvre produite � l'atelier et comme l'oeuvre de Bronzino lui-m�me. En fait, selon des recherches en histoire de l'art, Bronzino produisait en effet des r�pliques de ses oeuvres. Une comparaison de la composition et des r�sultats d'analyse qualitative fut men�e entre les deux oeuvres. Les diff�rentes m�thodes d'analyse utilis�es incluent la radiographie, la fluorescence de rayons X, la r�flectographie dans l'infra-rouge, l'examen � l'oeil nu, l'analyse de coupes transversales sous microscope, et enfin la microscopie en lumi�re polaris�e. TITULO—Evidencia de replicaci�n en un retrato de Eleonora de Toledo de Agnolo Bronzino y su taller. RESUMEN—Recientemente fue limpiado y consolidado un retrato de Eleonora de Toledo y su hijo, de la colecci�n del Instituto de Bellas Artes de Detroit, atribuido a Agnolo Bronzino. Este retrato es casi id�ntico a un retrato de Bronzino que se encuentra en la Galer�a Uffizi. El retrato de Detroit desde hace tiempo ha sido considerado por los eruditos como una replica, o sea una copia hecha por el artista. La evidencia material, de composici�n, t�cnica y cualitativa recolectada durante el tratamiento apoy� total o parcialmente la identificaci�n del retrato de Detroit como una copia contempor�nea al retrato de la Galer�a Uffizi, como el producto de un taller y como obra del mismo Bronzino. La investigaci�n de historia de arte estableci� que la t�cnica de replicaci�n era una costumbre de Bronzino. Fueron llevadas a cabo comparaciones cualitativas de composici�n entre los retratos de la Galer�a Uffizi y de Detroit. Los an�lisis incluyeron radiograf�as, fluorescencia de rayos X, reflectograf�a infrarroja, an�lisis visual y de secciones transversales, y microscop�a de luz polarizante. 1 INTRODUCTIONPortrait of Eleonora of Toledo and Her Son(fig. 1) entered the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1942 after having been there on loan since 1923. Its provenance extends only to the mid-19th century, when it appeared in Britain in the Hamilton Collection. Its conservation records list minor treatment for flaking in 1930, revarnishing in 1948, cleaning in 1955, and treatment for additional flaking in 1974 and 1977. In 1994, serious local cleavage was observed in the portrait. It was removed from the gallery to the Conservation Services Laboratory for treatment.

The Detroit portrait is a copy of the Portrait of Eleonora of Toledo and Her Son by Agnolo Bronzino in the Uffizi Galleries (fig. 2). It had always been judged by scholars to be a replica, a copy of the original made by the artist. However, the degree to which it is autograph has been disputed. Some scholars believed it to be wholly by Bronzino (Berenson 1963) and others wholly a workshop piece (McComb 1928).

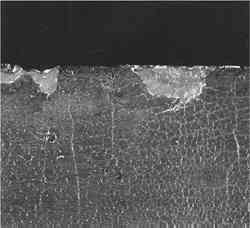

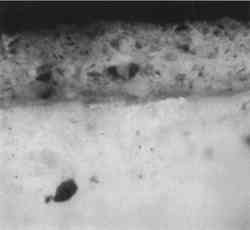

Visual and material analysis conducted on the occasion of the conservation treatment addressed the issue of autography. The evidence garnered during treatment was material, compositional, technical, and qualitative in nature. It variously addressed the hypotheses that support identification of the Detroit portrait as a replica. These hypotheses are (1) that the Detroit portrait is a contemporary copy of the Uffizi portrait; (2) that it was produced by a workshop; and (3) that it was painted at least in part by Bronzino. 2 HISTORICAL BACKGROUNDAgnolo Bronzino (1503–72) was court painter to Cosimo de'Medici, the duke of Florence from 1537 to 1574. Close to 100 extant portraits of Cosimo have been attributed, at one time or another, to Bronzino. There are 25 versions of Cosimo in armor alone. While certainly not all the portraits are autograph, Bronzino was known to have executed copies commissioned by Cosimo. The following exchange is recorded between artist and patron: “As soon as [Cosimo] saw Bronzino's finished portrait, he ordered it sent off to the emperor. And when Bronzino offered to paint another, still better, he replied, ‘I don't want another more beautiful. I want one done exactly the way it is already’” (quoted in Cochrane 1973, 52). The Portrait of Eleonora of Toledo and Her Son in the Uffizi, one of many portraits Bronzino painted of Cosimo's wife and their eight children, was completed around 1545, when Eleonora was 23 and the child, generally believed to be Don Giovanni, was 2. It is the best known of the portraits of Eleonora, not least because of her magnificent dress. It is characteristic of Bronzino's official portraiture in its polished surface, perfect rendering of texture, richness of the color, static quality of the sitter, and slightly off-center gazes of both subjects. Eleonora is presented as an icon, the duchess of Florence, wife of the reigning duke. She is reserved, distant, encased in a veritable fortress of a gown. The presence of Don Giovanni, however, adds an emotional element. Eleonora curves her proper right hand protectively around her son's shoulder. He leans slightly against her, resting his proper left hand on her lap like a plump starfish. His rucked collar suggests a fidgety little boy trying to stand still. Eleonora's gown is a powerful presence in the picture. There are several other portraits of Eleonora wearing this garment. Some scholars have theorized an iconographic significance to it, suggesting that it represents the wealth she brought to her marriage to Cosimo in the form of a dowry of Spanish textiles (May 1965). There is an apocryphal story that she was buried in the gown. In fact, Eleonora was buried in a red satin and velvet gown, which was less richly embroidered. According to the account of the disinterment of her tomb in 1857, she was found to have been buried wearing the gold and pearl hairnet seen in the portrait, which may account for the misunderstanding (Arnold 1995). It has also been suggested that Bronzino was merely given a piece of fabric with which to create the garment for the portrait (Landini 1995), though this seems unlikely given the number of portraits showing her in the gown. The Museo Nazionale del Bargello possesses two textiles manufactured in mid-16th-century Florence that are remarkably similar to the fabric of the gown. However, the pieces are described as silver and white silk, with a design in green cut velvet, and gold and silver brocades.1 At this point it is not known if Eleonora's magnificent gown ever existed, at least in the colors shown in the portrait. 3 MATERIAL EVIDENCEThe material evidence primarily addresses the date of the Detroit portrait. It appears to be contemporary with the Uffizi portrait. The panel's material, construction, and condition are typical of 16th-century Italian painting. The paint displays the crackle and patina characteristic of a painting of this age. No nonperiod pigments were found. The most visible material difference between the two portraits is the background color. The background of the Uffizi portrait is a rich deep blue. Conservation records from 1960 in the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence list the pigment as ultramarine, though there is no indication of analysis having been performed. It certainly appears to be true ultramarine. In fact, one scholar has recently linked a letter from Bronzino to the Uffizi portrait. The letter, written in the summer of 1545, is to Riccio, Cosimo de'Medici's majordomo. Bronzino is painting a In contrast to the Uffizi portrait, the background of the Detroit portrait is a gray green. The paint is extremely degraded. The medium has discolored to a light brown, and the pigment seems only to exist as discrete islands in the degraded medium. Severe traction crackle presents a leathery texture, which is particularly evident in the dark areas. At the top edge of the painting, where the rabbet has protected the paint, a less degraded area shows that the background had been blue (fig. 3). After cleaning, a previous repair to the panel at the upper right corner was exposed. The surface of the painting had been planed, and a layer of lavender pigment was revealed under the originally blue background. The blue and the lavender were identified by x-ray fluorescence and polarizing light microscopy. The upper layer is smalt mixed with lead white, and the lower is a red lake mixed with lead white. A cross section taken from a light area of the background shows the layering and the darkening of the degraded medium at the top of the sample (fig. 4). The degradation of the background paint is noticeably less advanced in areas where more lead white is present.

The background of the Detroit portrait is a textbook example of degraded smalt, the pigment discoloring to “a curiously unpleasant greyish green, slightly mottled with brown” (Plesters 1969, 65). The smalt, known to have been used in 16th-century Italian painting, has aged in the Detroit portrait over a significant period. It is clear, however, that the initial layering of cool pale blue smalt on lavender was a deliberate attempt to mimic the deep rich blue background of the Uffizi portrait without going to the expense of true ultramarine. Thus the Detroit picture is literally less valuable in terms of the costs of the pigments, which supports the idea that it is a copy of the more expensive Uffizi portrait. Another difference in color is found in Don Giovanni's costume. In the Uffizi portrait it is a rich violet shot with gold highlights. In the Detroit portrait the costume now appears as a light brown shot with gold. Initial analysis by x-ray fluorescence of the brown and gold suggests the presence of smalt and vermilion, along with lead-tin yellow and earth pigments. If the gold 4 COMPOSITIONAL EVIDENCEThe Detroit portrait is painted on a larger panel than the Uffizi portrait, though both are poplar. Preliminary investigation suggests that neither have been trimmed. The Detroit panel is 6.5 cm higher and 4.0 cm wider. The vertical joins in the panel fall awkwardly, each running through one of Eleonora's arms. In the Uffizi portrait, the center panel appears to be wider, with the vertical joins in the background to either side of her figure. The larger panel in the Detroit portrait has resulted in an extension of the image on the right and left sides and at the bottom of the composition. Preliminary measurements of the figures in each portrait demonstrate a close correspondence in dimension. The measurements of the Uffizi portrait were taken through the glazing; therefore a certain percentage of error is presumed. However, overall there was a close correspondence between the sizes of the faces and torsos of Eleonora and Don Giovanni in the two portraits. Most of the measurements were identical or within one centimeter of each other. For example, the distance between the top of Eleonora's head and the bottom of her proper left cuff is 47.3 cm in each portrait. The measurements support the use of a cartoon to produce the Detroit portrait, though no underdrawing was found with infrared reflectography, perhaps because of the extensive use of carbon black in the dress. An exact-size cartoon of the sitters was most likely made by the workshop, perhaps from the Uffizi portrait. The copyists did not bother to trim the panel to exact size, which would seem to have been an easier proposition than expanding the image. This decision implies a certain confidence in the copying process, which would more likely be found when a replica was being produced by the original artist's workshop. In fact, Bronzino's use of a cartoon to execute an expanded copy of a portrait of Cosimo de'Medici has been proposed elsewhere (Simon 1983). 5 TECHNICAL EVIDENCEThere are a number of technical indications that the Detroit portrait was painted by more than one hand. These include evidence of piecework fabrication, areas of misunderstandings in the division of labor, limited overlaps of paint, errors in extending the image, and simple copying errors. 5.1 PIECEWORK FABRICATIONOn close examination it is evident that the Detroit portrait was painted one section at a time. There are burrs, or small walls of dried paint, between the separate parts of the composition (fig. 5). Found throughout the Detroit portrait, these burrs are most visible at the intersections of the costumes with the faces or hands. The burrs of paint surrounding the heads of Eleonora and Don Giovanni, and especially their hands, are the most pronounced. These areas were carefully outlined and left absolutely in reserve as the rest of the composition was painted. The burrs were not disturbed by the slight overlap of paint from the reserved areas, indicating that enough time had passed for the paint on the initial parts of the composition to dry. Where there is a slight overlap of paint the underlying

5.2 BORDER MISUNDERSTANDINGSThat the various pieces of the composition were painted by different hands is indicated by two visible misunderstandings between the painters of separate areas. One of these areas is around Don Giovanni's head (fig. 7). The background painter left a reserve area for the head but along one side produced an irregularity in the contour. This irregularity now appears as a lump above Don Giovanni's ear, which the painter of the head has sparsely covered with fine strands of hair. The contrast to the hair painted on the background, above the irregularity, gives Don Giovanni the appearance of a bald spot on one side of his head. No doubt it is now more pronounced because of the darkening of the background.

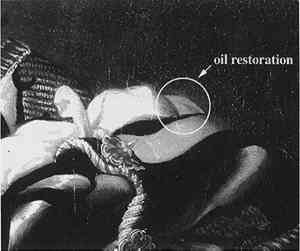

The second border misunderstanding is at Eleonora's proper left shoulder. In the Uffizi portrait a small linen tag from her underblouse twists and loops over at the top of her shoulder (see fig. 2). The blue background is visible under the loop. In the Detroit portrait, the background painter has left a blank space for the loop, but the sleeve painter did not fill it (fig. 8). An old, irremovable oil restoration, a wedge of medium gray, now occupies the blank area, but the original light brown can be seen around it. Again, the area is more prominent because of the darkening of the background.

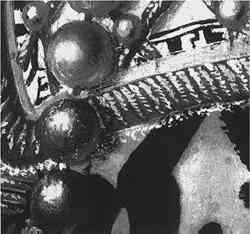

5.3 OVERLAPPED PAINTOf the several contributors to the Detroit portrait, the painter of the heads and hands was the only artist to impinge on other areas of the painting, as shown around Eleonora's proper left hand (see fig. 6) and at the side of Don Giovanni's head (see fig. 7). In addition, an x-radiograph of the Detroit portrait shows that the lower string of Eleonora's pearl necklace was painted on top of the dress, while the upper string was painted at the same time as her throat (fig. 9). Under magnification, the impasto of the dress's gold trim appears through one of the pearls in the lower string (fig. 10); in the same manner the overlapping paint around Eleonora's hands covers adjacent impasto. No overlaps of paint are found in other areas of the composition in the Detroit portrait.

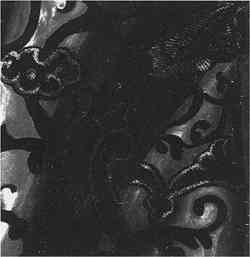

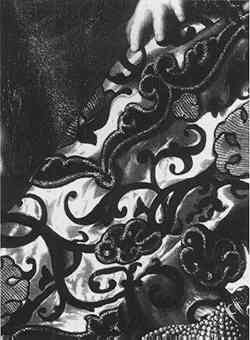

5.4 ERRORS IN THE EXTENSION OF THE IMAGEThe Detroit portrait is on a larger panel than the Uffizi original, meaning that parts of the image had to be created rather than copied. The 6.5 cm expansion of the dress at the bottom of the Detroit portrait is one such area. At the bottom left corner of the skirt in the Uffizi portrait, the top of one of the large gold brocades shows at the very edge of the panel (see fig. 2). These motifs appear regularly over the fabric. Examination of the fabric pattern shows that the brocade at the bottom edge is a duplicate of the motif on Eleonora's torso. At the bottom left of the Detroit portrait, however, it dissolves into a lumpy chevron where it has been extended to fit the larger panel (see fig. 1). It is unlikely that the skirt painter ever saw the fabric or the dress itself but was working directly from the Uffizi portrait. By inference, it is unlikely that this painter was Bronzino, who demonstrates a good understanding of the fabric in the original portrait. 5.5 COPYING ERRORSSimilar misinterpretations of the original occurred in copying directly from the Uffizi portrait. For example, the landscape at the center right of the Uffizi portrait shows a river curving around the green shore on the right side (see fig. 2). In the Detroit portrait the river and shore have been transformed into an amorphous whirlpool (see fig. 1). Simpler misinterpretations of the original design are also present. In the vertical fold of the skirt at the lower right, beside the red bench, a black line of cut velvet jumps over two folds rather than following the contours of the satin (fig. 11). The same general effect of the black design lying on top of the draped satin can be seen throughout the skirt in the Detroit portrait, particularly when it is compared to the handling of the design in the Uffizi portrait.

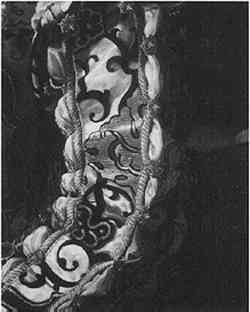

6 QUALITATIVE EVIDENCEDifferences in the quality of the painting are evident when the two portraits are compared. A comparison of the quality of the various hands within the Detroit portrait also proves useful with respect to workshop production. 6.1 QUALITATIVE COMPARISON TO THE UFFIZI PORTRAITThe overall quality of the painting in the Uffizi is superior to that of the Detroit portrait. The difference can be seen even in the handling of the background tones. In spite of the darkened smalt, a certain awkwardness of modulation remains evident in the Detroit portrait. Eleonora's head is surrounded by a U–shaped area of lighter paint. In the Uffizi portrait, the lighter tones of the background fade gracefully off to the sides and behind her figure (see figs. 1, 2). The dress is more believable as a three-dimensional form in the Uffizi portrait, its intricate design securely attached to the undu 6.2 QUALITATIVE COMPARISON WITHIN THE DETROIT PORTRAITMuch of the technical evidence in the Detroit portrait points toward several hands having been involved in its production. It is also evident that these hands were of varying talent. For example, the painter of the background, who may also have painted the landscape, was not particularly attentive. He did not paint the upper portion of the dress, as evidenced by the space he left for the missing linen tag, or Don Giovanni's head, because of the irregularity he left in its contour. The more talented hands in the portrait tend to fall in the visually more important areas of the composition, as would be expected in a workshop production. For example, the clumsiest area of the dress with respect to the handling of the paint is found in the lower left side of the skirt, a relatively unimportant area (fig. 12). The highlights are harsh and virtually illegible with respect to describing the drapery. The small gold-brocaded motifs rest lightly on the fabric, almost as if they could slide off the satin at any moment. The inferior quality of the painting in this area is particularly obvious when it is compared to other, more compositionally prominent, parts of the dress. In Eleonora's proper left sleeve, for example, the highlights in the satin are soft and well placed along the rucked surface of the fabric (fig. 13). The brocaded motif is properly distorted as it undulates. The black design is much more a part of the satin surface. The small linen pouches protruding from underneath are believably rendered in gray and white. The painter of this sleeve was a better artist than the one who painted the lower left skirt.

6.3 QUALITATIVE EVIDENCE OF BRONZINOEvidence that the painter of Eleonora's and Don Giovanni's faces in the Detroit portrait was Agnolo Bronzino is primarily qualitative, though supported by scholarly opinion. As would be expected in a workshop production, the painter of the most important parts of the Detroit portrait, the faces and hands, is superior to all others in the piecework fabrication. The paint has been applied with confidence; no reworking is visible. The lower string of the pearl necklace, painted directly on the finished dress, shows no indication of hesitation on the part of the artist, who at this point was certainly working without an underdrawing. The extreme care with which the other painters kept within the The quality of the painting is characteristic of Bronzino's work. The still expressions are found in most of his formal portraits, as are the off-center gazes which appear to focus on a point behind the viewer. Typical of his technique, paint is built up in thin layers to produce forms of a characteristic impenetrable hardness. Almost imperceptibly applied warm glazes of color and shadow render the forms as polished three-dimensional faces. This luminescent flesh is typical in his portraiture, as is the absence of visible brush strokes. The faces in the Detroit portrait suffer only in direct comparison to the those in the Uffizi original. The Detroit subjects are very slightly less lively. While their quality supports the presence of Bronzino's hand, the somewhat removed effect in their expressions suggests that Bronzino copied Eleonora and her son from the Uffizi portrait rather than painting them from life. This approach would be expected when a replica is being produced. 7 CONCLUSIONSMaterial evidence supports a date for the Detroit portrait contemporary with the Uffizi portrait. The materials and panel construction are typical of the period. The condition of the painting is in keeping with its age. The use of smalt, red lake, and lead white demonstrate that the background of the Detroit portrait was once similar to that of the Uffizi picture, though executed in less costly materials. The use of a cartoon to create the Detroit portrait is supported by the similarity of the dimensions of the subjects. Art historical research established replication and the use of a cartoon for a larger replica as a part of Bronzino's studio practice. The Detroit portrait as a collaborative product is supported by technical and qualitative evidence. Piecework fabrication, border misunderstandings, limited overlaps of paint, and errors in extending and copying the design indicate the presence of several hands. The more talented artists painted the more important parts of the portrait, as would be expected in a workshop. Qualitative evidence supports the identification of Bronzino's hand in the most important parts of the Detroit portrait, the faces and hands. The superior quality of the painting is commensurate with that found in Bronzino's known portraits. While none of the material, compositional, technical, and qualitative evidence garnered during the recent treatment of the Detroit portrait proves by itself that the portrait is by Bronzino and his workshop, the evidence taken as a whole is quite persuasive. The cumulative effect of this evidence concerning the degree of autography, along with scholarly opinion, led to the reattribution of Portrait of Eleonora of Toledo and Her Son in the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts from Agnolo Bronzino to Agnolo Bronzino and Workshop. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe author would to thank the Detroit Institute of Arts, in particular Paul Cooney for the photography and x-ray and infrared imaging; Dr. Leon Stodulski for the x-ray fluorescence and cross sections; Alfred Ackerman, Iva Lisikewycz, Julie Moreno, and George Keyes for their professional support; Dott.ssa Caterina Caneva and Giovanna Giusti at the Gallerie degli Uffizi; Gianni Marussich, Marina Marussich, and Stefano Scarpelli for their assistance in Florence; Claudia Lazzaro at Cornell University and Ann Vasaly at Boston University for their editorial comments; and the Rockefeller Foundation. NOTES. Firenze, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Collezione Carande, nos. 2402 and 2402/C. “Teletta d'argento con velluto, Fondo di teletta d'argento; disegno di velluto tagliato e REFERENCESArnold, J.1995. Cut and construction. In Moda alla corte dei Medici: Gli abiti restaurati di Cosimo, Eleonora e don Garzia. Florence: Centro Di della Edifimil. 49–73. Berenson, B.1963. Italian pictures of the Renaissance. London: Phaidon Press. Cochrane, E.1973. Florence in the forgotten centuries, 1527–1800. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Landini, R. O.1995. L'amore del lusso e la necessita della modestia Eleonora fra sete e oro. In Moda alla corte dei Medici: Gli abiti restaurati di Cosimo, Eleonora e don Garzia. Florence: Centro Di della Edifimil. 35–45. May, F.1965. Spanish broacades for royal ladies. Pantheon23:8–16. McComb, A.1928. Agnolo Bronzino: His life and works. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Plesters, J.1969. A preliminary note on the incidence of discolouration of smalt in oil media. Studies in Conservation14:62–74. Santi, B.1976. Neri di Bicci Le Ricordanze. Pisa: Edizioni Marlin. Simon, R. B.1983. Bronzino's portrait of Cosimo in armour. Burlington Magazine. 125:527–39. AUTHOR INFORMATIONSERENA URRY received a B.A. in art history from Tufts University and an M.A. in art history and diploma in conservation from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Since 1989, she has worked at the Detroit Institute of Arts, where she is currently an associate conservator of paintings. In March 1997 she was a scholar-in-residence at the Rockefeller Foundation's Bellagio Study and Conference Center, where much of this article was written. Address: Detroit Institute of Arts, 5200 Woodward Ave., Detroit, Mich. 48202.

Section Index Section Index |