TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AFTER THE BOMB: MAINTAINING CLEVELAND'S THE THINKERBRUCE CHRISTMAN

ABSTRACT—The Cleveland Museum of Art's The Thinker has a unique history in relation to the other original casts supervised by Rodin. In 1970, the museum's Thinker was blown up by radical protesters. This article will explore some of the complex ethical and practical issues surrounding its treatment. Of equal interest is the history of protective coatings that have been used on the sculpture. The records available at the Cleveland Museum of Art show early concern over changes in The Thinker's patina by the museum's first director, who sought advice on its care. In the past, wax and two commercial oil preparations were applied as protective coatings. Currently The Thinker has been stabilized with an Incralac coating and is washed and waxed twice a year. TITRE—Vingt-cinq ans apr�s la bombe: l'entretien du Penseur de Cleveland. R�SUM�—Le Penseur du Cleveland Museum of Art poss�de une histoire unique par rapport aux autres moulages originaux cr��s par Rodin. En 1970, un groupe de manifestants radicaux fit exploser la statue. Cet article examine quelques-uns des aspects d�ontologiques et pratiques complexes qui survinrent pendant la restauration du Penseur. Un aspect int�ressant du travail fut la mise � jour de l'histoire des couches protectrices qui furent appliqu�es sur la statue. Des archives du Cleveland Museum of Art montrent que le premier directeur du mus�e s'inqui�ta du changement survenu dans la patine du Penseur et chercha conseil pour sa pr�servation. Dans le pass�, de la cire et deux pr�parations commerciales � base d'huile furent appliqu�es comme couches protectrices. Actuellement, Le Penseur a �t� stabilis� avec une couche d'Incralac; il est lav� et cir� deux fois par an. TITULO—Veinticinco a�os despu�s de la bomba: el mantenimiento de “El Pensador”. RESUMEN—La estatua de “El Pensador” del Museo de Arte de Cleveland, cuya fundici�n fue supervisada por Rodin, comparada con otras, tambi�n supervisadas por Rodin, tiene una historia singular. En 1970 una bomba puesta por elementos radicales la hizo explotar. Este art�culo se dedica a explorar algunos de los complejos asuntos �ticos y pr�cticos relacionados con el tratamiento de conservaci�n de la escultura. De igual inter�s es la historia de las capas protectoras que se han usado sobre la escultura. Los documentos en los archivos del Museo de Arte de Cleveland demuestran la preocupaci�n temprana del primer director del Museo en cuanto a los cambios observados en la p�tina de “El Pensador”, quien solicit� consejo sobre el cuidado de la escultura. En el pasado, capas de cera y dos preparaciones comerciales en base de aceite fueron aplicados como agentes protectores. Actualmente, “El Pensador” ha sido estabilizado con una capa de Incralac y se lava y se encera la obra dos veces al a�o. 1 INTRODUCTIONThe history of The Thinker at the Cleveland Museum of Art is unique in relation to the other original casts supervised by Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) (see appendix). Shortly after the sculpture was acquired in 1917, the director of the museum sought advice about its maintenance outdoors from Frank Purdy of the Gorham Company. Purdy, a prominent expert, also gave advice to other museums and collectors during the early years of this century, so it is likely that many outdoor bronzes in this country The museum's records on The Thinker are of interest to conservators not only as they document early conservation practices for outdoor bronzes but also as they explore complex ethical and practical issues surrounding the treatment of damaged art. 2 HISTORY OF TREATMENT, 1916–1970Records about the care of The Thinker come from three sources—the museum's archives, the curatorial records, and Conservation Department records. As might be expected, over a halfcentury these records are uneven and often sketchy. In the early years, day-to-day records and correspondence document the treatment the sculpture received during the administration of Frederick Whiting, the museum's first director (May 1913–August 1930). Records of treatment stop in 1925. The museum's Conservation Department was established in 1958, and before that date conservation work was undertaken by a number of outside conservators, notably William Suhr and Rostislav and S. N. (Nicky) Hlopoff. Information presented here also comes from personal communications with the late Frederick Hollendonner, former chief conservator, and with Superintendent Victor Kavosic, Cleveland Police Department, and from direct observation of coating procedures carried out at the museum. The Cleveland Museum of Art acquired The Thinker in 1917 (1917.42), one year after the museum opened its doors, as a donation from Ralph King. First displayed inside in the rotunda (fig. 1), within several months the sculpture had been moved outside to the south entrance of the museum (fig. 2). In a letter dated February 2, 1918, to Miss Anna Seaton-Schmidt, a pupil and friend of Rodin, Whiting explained this move.

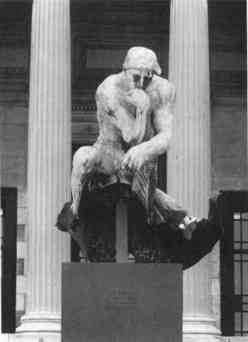

Anna Seaton-Schmidt replied on February 7, 1918, expressing her delight that the museum had been fortunate enough to acquire The Thinker. As to the sculpture being placed outdoors, she wrote: She emphasized in another paragraph: “Above all it must be high. Even the one in front of the Pantheon is not high enough, but that could not be helped.” Once the sculpture was outside, Whiting noticed problems with the patina almost immediately. Two letters provide insight regarding the appearance of the original patina. In a letter dated October 9, 1917, to Malvina Hoffman, another student and friend of Rodin, Whiting wrote: Whiting went on to ask what Rodin would have wanted under the circumstances. Unfortunately, Malvina Hoffman's reply does not exist in the archives. The color of The Thinker is again mentioned in a letter to Purdy of the Gorham Company, dated October 22, 1917. “The large bronze replica of ‘The Thinker’ by Rodin which Mr. Purdy would become a key player, advising the museum on care for the sculpture. Letters between him and Whiting, from 1917 to 1921, are the earliest records regarding the care of the sculpture. On October 24, 1917, Purdy recommended: Whiting's reply, on November 2, sheds some light on this hand rubbing method: On October 31, Purdy instructed:

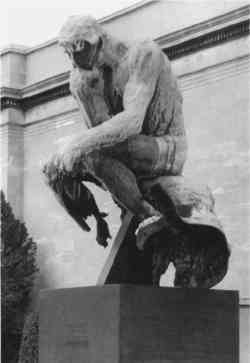

By June 1920, Purdy had changed his thinking on the care of outdoor bronze sculptures and advised the museum to apply wax to The Thinker. On June 10, Whiting described the new stone pedestal for The Thinker as already somewhat discolored by the bronze figure and asked if the wax would stop the staining of the stone base. He also complained that the figure looked dull. Could the wax be buffed? In Purdy's reply, dated June 24, Purdy asserted: “The wax coat should prevent further discoloration By April 1921, Whiting asked if Purdy would be in Cleveland in the near future “as there seems to be a constant running of the color, despite the treatments with the wax preparation, and the artificial stone base is fast becoming a greenish color from this cause. We do not object to the discoloration of the base, but it seems to indicate a deterioration of the bronze, which may be disastrous in time, if allowed to continue.” In 1921, Whiting inquired about purchasing more wax from Gorham Company and was reassured by Purdy that applying another coat of wax would cause no harm. After 1925, there are no records on the routine care of The Thinker in either the archives or the curatorial files. It is not clear why the records suddenly stop at this point. Frederick Whiting remained as director until August 1930 and it is unlikely that problems with The Thinker stopped suddenly or that Whiting's concern was any less. Perhaps Purdy retired from Gorham Company, or more likely the written correspondence was replaced by the telephone. In any case, at some later date the art handlers were sent outside with Gorham Company's AB Mixture—a petroleum-based product—and instructed to coat the sculpture with this material.1 This treatment was certainly being carried out from the 1950s onward. The museum's second director, William Milliken (August 1930–March 1958), may have started this practice, perhaps advised by the Gorham Company, which was marketing a new product. It is not clear how often the oil was applied to the sculpture. By the late 1970s the application of the AB Mixture was somewhat sporadic. The product applied to the sculptures was also changed at this point because AB Mixture was no longer available. Birchwood-Casey's Sheath Rust Preventive was used and is a similar, although more sophisticated, product containing corrosion inhibitiors.2 The results of these past treatments ranged from little to moderate protection for The Thinker. The earliest treatment recommended by Purdy—rubbing the sculpture with the hands and a cloth–seems to have been more aesthetic than truly protective. Purdy did not elaborate on how this rubbing treatment would stop corrosion. It seems that several things—both aesthetic and protective—may have happened with this treatment. The rubbing of the bronze surface may have removed dirt and pollutants as well as any residual patination chemicals not carefully washed from the bronze. The oil from the hands would help saturate the surface, thus making it appear more visually integrated. Oil from the hands may also have imparted some protection from water. However, this treatment would also have introduced salts and acids that, over the long run, could not have been beneficial. One can only speculate that Purdy had observed areas of bronze sculptures that had developed a lustrous patina from constant handling and formed the opinion that rubbing with the hands was good for the bronze. The composition of Purdy's wax was not given, but it must have provided more protection from the elements than the hand and cloth rubbing. He recommended that it be applied twice a year but did not recommend heating the wax or the sculpture. The protection given by It is evident that as long as the oil stayed in place, it did provide a modest amount of protection for the bronze. Unfortunately the various protective coatings do not seem to have been applied in a routine and systematic way. So, the protection of The Thinker from weathering has been uneven. It is clear that The Thinker would have been better preserved if it had been attended to on a more regular schedule. Purdy's influence on the treatment of outdoor bronze sculptures should not be underestimated. From the references in the correspondence, he was obviously concerned about preservation and was influential at several levels. He described his methods at a Metropolitan Museum of Art conference in the spring of 1917. While little is known about this meeting, it seems likely that representatives from many of the major museums in this country attended. Purdy was also involved in a project with Colonel Harts of the Bureau of Weights and Measures to preserve public monuments. At this time they were promoting the hand-rubbing method. Purdy also seems to have been speaking to artists, specifically to Auguste Rodin. It is not known if he expressed his views on preservation to Rodin, but he had close ties to the sculptor as he essentially acted as a dealer for him. 3 EXPLOSION, MARCH 24, 1970In the early morning hours of March 24, 1970, dynamite was placed between the legs of The Thinker. The results were devastating (fig. 3). The base and the lower part of the legs were annihilated, and the remaining sculpture was knocked off of its pedestal. The Thinker lay face down, apparently contemplating Hell much more directly. The blast sent pieces of bronze flying, causing damage to the building approximately 20 yards away. The bronze doors of the museum were dented, and the marble columns were chipped. This damage can be seen to this day. Pieces of bronze were even found on the roof. According to the Cleveland Police Department, this act of terrorism was conducted by a radical Weatherman group operating in Cleveland. Members of the group later moved to New York City, where they were killed making explosives.

The sculpture sustained considerable trauma. The obvious damages mentioned above were the loss of the feet and lower areas of the legs. The seat supporting the figure was severely distorted. The sculpture also sustained damage not so easily seen. The explosion caused much of the lower half of the sculpture to expand and to be A number of treatment options were examined and contemplated by Edward Henning, curator of modern art; Frederick Hollendonner, objects conservator; and Sherman Lee, third director of the museum (April 1958-June 1983). Noted experts, both art historians and conservators, were consulted on the issues surrounding The Thinker. Again, the archives and the curatorial files contain a wealth of information. A number of opinions were expressed, ranging from mounting the object as it was to obtaining a new cast from the Rodin Museum. One of the more knowledgeable and reasoned letters came from Professor Albert Elsen, Stanford University, to Sherman Lee, dated June 18, 1971:

Essentially, the museum studied three treatment options: (1) take molds from other original Thinkers and make a replacement cast; (2) make a cast from molds and cut the newly cast sculpture up to replace damaged areas of the Cleveland sculpture; or (3) mount the damaged sculpture and essentially do no restoration. Joseph Ternbach, a conservator in private practice specializing in metal conservation, acted as a consultant to help study the practicality of the options. Considering the extent of damage and the difficult ethical issues there was no obvious or perfect solution. The making of a new cast after the death of an artist is always problematic. Casting sculptures in bronze is a technique that lends itself to accurate multiple reproductions. The original Thinker owned by the Cleveland Museum of Art was one of the few that had been cast and patinated under the supervision of Rodin. A number of other Thinkers were cast shortly after Rodin's death, and the Rodin Museum continues to make sculptures for sale. At what point does a recast become a reproduction? In Sherman Lee's opinion casting a new sculpture would lack the quality of either the original or even those cast shortly after Rodin's death. It was felt a recast in this situation would in essence be a reproduction. Cutting and welding a new cast to the original were fraught with technical problems. The whole reproduction process of taking a new mold, making a wax model, and casting a new bronze sculpture generally results in significant shrinkage of 5–10%. Matching up parts with different proportions would result in parts that There was also significant distortion of the lower parts of the sculpture, because the explosion expanded the metal in some areas. Even if an exact match in size could be achieved the pieces would not have aligned well due to the changes in the sculpture's dimensions. The other option would have been to cut away the expanded areas of the sculpture in order to achieve a better fit, but significantly more of the original sculpture would be lost. Perhaps less than half of the sculpture would remain. Even if all the technical problems were overcome and the new pieces were matched up to the original sculpture, other ethical issues developed. How far does one take the visual integration of the two parts? Should the new areas be patinated a slightly different color from the original so that viewers could differentiate the original sections from the made-up sections? Would Rodin have approved of the aesthetics of a two-toned sculpture? The last option of mounting the sculpture in its damaged state also had significant ethical implications. This option would preserve what was left of the sculpture directly supervised by Rodin but sacrifice some of the artist's original intent. While Albert Elsen states that Rodin did accept happy accidents in the creative process and used partial sculptures to edit his students' works, there is no clear evidence that he would have been happy leaving the sculpture in its damaged state. It is interesting to reflect that ever since the British Museum mounted the Elgin Marbles as fragments in the 19th century, we have come to accept the concept of a fragment from a sculpture as being a complete work of art. For most classical sculptures we do not know what the original complete sculptures looked like, and doing any type of restoration would be both impossible and unethical. However, the original form of Cleveland's Thinker is well known. The mounting of the sculpture in its damaged state turns The Thinker from being purely an art object into a historical document. For better or worse, an antisocial statement had been made and has now become part of the history of this particular sculpture. As the correspondence in the curatorial files and the archives show, these issues were explored with curators, museum directors, conservators, and artists. After discussing the implications of the three options, the third was selected for a number of reasons. First and foremost, this option preserved what was left of the original sculpture. The first option (making of a new cast) was rejected because it would be a replica and not a cast personally supervised by Rodin. The sculpture had become so distorted by the expansion of the metal during the explosion that the second option could not be seriously considered. Sherman Lee summed up the museum's final position in a letter to Professor Albert Elsen, dated June 15, 1971: The sculpture was then mounted on a bronze armature and placed on a tall granite pedestal with the inscription “The Thinker / by Auguste Rodin / Gift of Ralph King / (and in smaller letters) Damaged 24th of March 1970.” There was little emotional reaction from the press and public to the museum's decision to place the damaged sculpture on view outside the museum (fig. 4). Nearly all of the newspaper

4 TREATMENT SINCE 1980In 1980, the museum began a program to maintain all of its outdoor sculptures—including The Thinker—on a more regular basis (fig. 5). The previous treatments of oil had left a fairly thick film, which had trapped a great deal of dirt, in the protected and lower areas of The Thinker. In order for any treatment to be successful, it was imperative to remove the oil.

The Thinker was first washed with Orvus anionic detergent and water. This successfully removed much of the dirt but not much of the oil. Acetone and cotton swabs were used to remove the oil. The application of acetone was repeated several times until there was no evidence of oil coming up in the cotton. Two thin brush coats of Incralac were applied followed by two spray coats. The Thinker was then given a final layer of wax. The Thinker now receives routine maintenance twice a year, in the spring and fall. It is washed with Orvus soap and rewaxed with either MinWax or Butcher's Bowling Alley Paste Wax. Any breaks in the lacquer are touched up. At the time The Thinker was treated with Incralac many conservators were using this product as a protective layer. It was felt that the acrylic coating would provide better protection for the sculpture in an outdoor environment. To date, the Incralac coating on The Thinker has not degraded enough to require its removal from the surface. Based on experience with several of the other sculptures in the museum collection, the removal of the Incralac is a slow process. Because of this difficulty in removal, the continued use of Incralac on The Thinker will need further study. More extensive treatment, such as aesthetic reintegration of the patina on The Thinker, was not done as the sculpture has been so radically altered by the bombing. So much of Rodin's artistic intent was altered by the bombing that the corroded surface is a relatively minor issue. This sculpture has taken on a life of its own–part Thinker by Rodin, part history, part social statement. A unique and haunting beauty has emerged. The museum's philosophy is to stabilize the sculpture in its present condition. Recent detailed examination of The Thinker indicates that there may be additional damage from the explosion. Deep pits are present on the legs and other lower surfaces. These pits are located within “sight line” of where the dynamite was positioned. They have ragged edges and seem to erupt from the surface, suggesting they may have been formed from the percussion of the explosion. Essentially, the pits are incipient tears and cracks in the metal. At the center of many of the pits are areas of light green corrosion, which may be caused by chemical residues left from the dynamite as it is not seen Another problem is the presence of wildlife inside the sculpture. Because the bottom of the sculpture is now open to the elements, birds found it is a great place to nest. The nests have now been pulled out, and nylon screening coated with tinted Incralac has been worked up inside of the legs and the figure to deter future inhabitation. 5 CONCLUSIONOver the years the Cleveland Museum of Art has tried to care for The Thinker using such measures as waxes and oils—often intermittently—to maintain the sculpture. The museum's current philosophy for its care is a conservative one. The sculpture has certainly changed—to say nothing of the surface—from the time that it left Rodin's studio. Much of Rodin's artistic intent has been significantly altered or lost. After the bombing, the museum staff made the decision to preserve what remained of The Thinker. The current goal of the museum is to keep its condition stable. A more aggressive treatment can be undertaken in the future. Not to treat an object is a valid treatment option, but it is not without ramifications. Much of the original artistic intent of the Cleveland Museum of Art's Thinker has been altered. What was once a sculpture has become a historical document. The museum has preserved what is left of Rodin's sculpture as well as something of America's social history in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In a letter to Sherman Lee, dated June 18, 1971, Professor Albert Elsen succinctly summed up the problem and the solution: “I know the temptation will be strong to show it as it is, which makes it above all a monument to an insane act.” ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSI would like to thank Diane O'Malia for her invaluable assistance in the archives of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Thanks is also extended to the Conservation Department for its encouragement and patience, especially to Patricia Griffin for her insights and constructive criticism and to Judith DeVere for her help in editing the manuscript. APPENDIX1 APPENDIXOther bronze casts of the enlarged version of The Thinker are listed below, by location: Argentina

Belgium

Denmark

France

Germany

Japan

Russia

Sweden

United States California

Colorado

Kentucky

Maryland

Michigan

Missouri

New York

Ohio

Texas

This list of other bronze casts of the enlarged version of The Thinker (130.2 � 140 � 200.7 cm) and their locations has been compiled from these sources: DeCaso, J., and P. B.Sander. 1973. Rodin's Thinker: Significant aspects. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco; Burlingame, Calif.: Demia Press. Elsen, A.1985. Rodin's Thinker and the dilemmas of modern public sculpture. New Haven: Yale University Press. 163, 164. Spear, A. T.1972. Rodin sculpture in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art. 96,97. Spear, A. T.1974. Supplement to Rodin sculpture in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art. 130S. Tancock, J. L.1976. The sculpture of Auguste Rodin. Philadelphia: Philadephia Museum of Art and David R. Godine. 121. NOTES1. The remnant of a can of the Gorham AB Mixture remains in the Conservation Department although it has not been analyzed. The label reads, “A conditioning oil for bronze with either natural or oxidized finish,” and the instructions are, “Dampen cloth with oil and apply a liberal coating to entire surface. Wipe dry and polish with clean cloth.” The following note is also given: “AB Mixture will not restore original color nor prevent darkening. It will with repeated applications produce the beautiful color characteristic associated with well kept bronze.” The last sentence sounds as if it might have been written by Frank Purdy, as the language and view are similar to those expressed in his letters. 2. Sheath Rust Preventive, made by Birchwood-Casey, Eden Prairie, Minnesota, is according to in a product data sheet from the 1970s, a “solvent-based, water displacing corrosion inhibitor, finger print neutralizer and lubricant for ferrous and nonferrous metals. It lays down a thin, transparent film which lifts moisture from metal pores. Prevents corrosion by sealing moisture out with a continuous polar protective film …. Penetrates and loosens rusty ‘frozen’ parts. Leaves a slightly oily film which will not gum under high humidity, high-temperature conditions. Harmless to plastics, rubbers, paints. Contains no silicone or wax.” The product is still being marketed by Birchwood-Casey as Sheath RBI Water Displacing Rust Preventive, and the description has not changed in 20 years. The current material safety data sheet states that the product contains mineral spirits (over 63% w/w), heavy petroleum oxygenates, barium-neutralized (under 18% w/w), mineral oil (under 15% w/w), and propylene glycol monomethyl ether (under 4% w/w). 3. The x-ray diffraction pattern was found to match JCPDS file number 30–0473, International Centre for Diffraction Data, 1997. 4. Cheddite I.S. contains 90% potassium chlorate, 7% paraffin, 3% petroleum jelly, and traces of carbon black. Cheddite O.S. Contains 90% sodium chlorate, 7% paraffin, 3% petroleum jelly, and traces of carbon black. Cheddite O extra contains 79% sodium chlorate, 23.2% nitro derivatives of toluene, and 1.8% nitrocotton. Leonid Trassuk and SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE CONSERVATION OF OUTDOOR BRONZE SCULPTUREChase, W. T., and N. F.Veloz. 1985. Some considerations in surface treatment of outdoor metal sculpture. AIC preprints, American Institute for Conservation 13th Annual Meeting, Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C.: AIC. 23–35. CRM Bulletin. 1984. Outdoor sculpture in the park environment. CRM Bulletin7(2): 4–5. Drayman-Weisser, T.1992. Dialogue/89—The conservation of bronze sculpture in the outdoor environment: A dialogue among conservators, curators, environmental scientists, and corrosion engineers. July 11–13, 1989, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Houston: National Association of Corrosion Engineers. Erhardt, D., et al. 1984. The durability of Incralac: Examination of a 10-year-old treatment. ICOM Committee for Conservation preprints, 7th Triennial Meeting, Copenhagen. Paris: ICOM. 84.22.1–84.22.3. Merk-Gould, L., R.Herskovitz, and C.Wilson. 1993. Field tests on removing corrosion from outdoor bronze sculptures using medium pressure water. ICOM Committee for Conservation preprints, 10th Triennial Meeting, Washington, D.C. Paris: ICOM. 772–78. Montagna, D. R.1989. Conserving outdoor bronze sculpture. Preservation Tech Notes. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service. Veloz, N. F., and W. T.Chase. 1989. Airbrasive cleaning of statuary and other structures: A century of technical examinations of blasting procedures. Technology and Conservation (Spring): 18–28. Weil, P. D.1975. The approximate two-year lifetime of Incralac on outdoor bronze sculpture. ICOM Committee for Conservation preprints, 4th Triennial Meeting, Venice, Italy. Paris: ICOM. Weil, P. D.1980. The conservation of outdoor bronze sculpture: A review of modern theory and practice. AIC preprints, American Institute for Conservation 8th Annual Meeting, San Francisco. Washington, D.C.: AIC. 129–40. SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY ON RODIN AND HIS SCULPTUREDeCaso, J., and P. B.Sander. 1973. Rodin's Thinker: Significant aspects. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco; Burlingame, Calif.: Demia Press. Elsen, A. E.1980. In Rodin's studio: A photographic record of sculpture in the making. Oxford: Phaidon Press. Elsen, A. E.1985. Rodin's Thinker and the dilemmas of modern public sculpture. New Haven: Yale University Press. Elsen, A. E., ed.1981. Rodin rediscovered. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. Spear, A. T.1972. Rodin sculpture in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art. Tancock, J. L.1976. The sculpture of Auguste Rodin. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art and David R. Godine. SOURCES OF MATERIALSButcher's Bowling Alley Paste Wax (wax mixture in turpentine and petroleum naphtha)Butcher Polish Co., 67 Foreft St., Marlborough, Mass. 01752 Incralac (Acryloid B-44 with benzotriazole and UV stabilizer)StanChem Co., 401 Berlin St., East Berlin, Conn. 06023 Minwax Paste Finishing Wax (wax mixture in turpentine and petroleum naphtha)Minwax Company, Inc., 16 Cherry St., Clifton, N.J. 07014, or, Flora, Ill. 62839 Orvus WA Paste (sodium lauryl sulfate)Conservation Support Systems, P.O. Box 91746, Santa Barbara, Calif. 93190 AUTHOR INFORMATIONBRUCE CHRISTMAN graduated from the University of Delaware/Winterthur Art Conservation program in 1979 and has worked as a

Section Index Section Index |