ULTRASONIC MISTING. PART 2, TREATMENT APPLICATIONSCAROLE DIGNARD, ROBYN DOUGLAS, SHERRY GUILD, ANNE MAHEUX, & WANDA McWILLIAMS

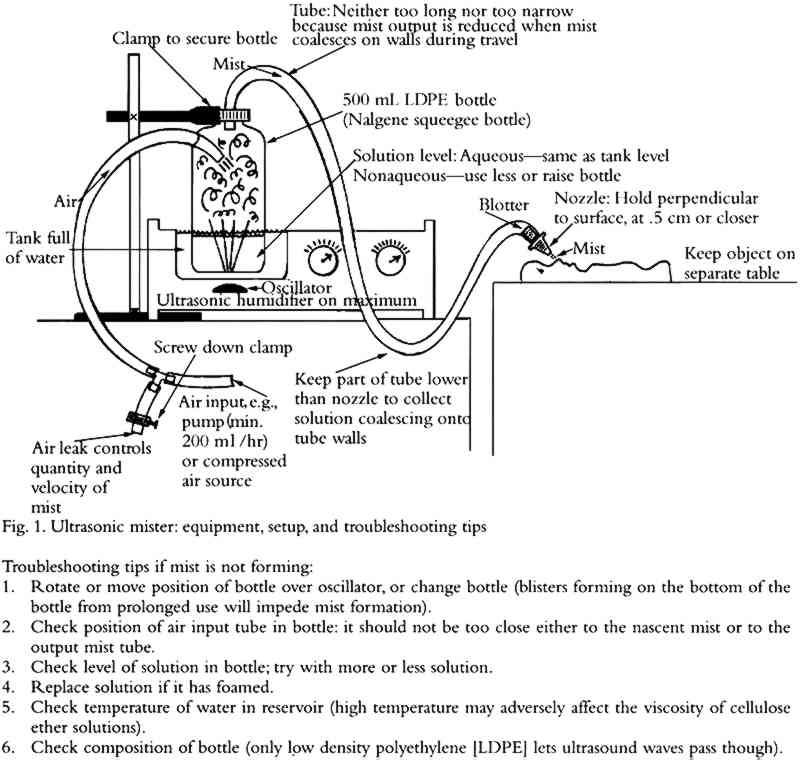

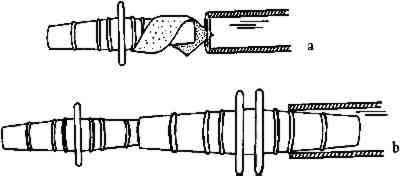

ABSTRACT—Ultrasonic misting is a technique useful for applying small amounts of dilute solutions to objects, particularly for the consolidation of pigment or other thin layers on various types of artifacts and works of art. The equipment is economical and easily assembled, and the method of application is straightforward, although it can be labor-intensive because several applications of a relatively low concentration of solution may be required to achieve good results. The ultrasonic mister's main advantage is that it offers a means of finely controlling the quantity, velocity, and location of the solution delivered. This control is most important when treating very fragile objects. In this paper, the equipment and commonly used consolidants are described, and the authors outline several examples of the application of the ultrasonic mister, including the treatment of the paper gauge of a mica compass, two charcoal drawings, an ink drawing with watercolor, a gouache painting, a pastel and gouache drawing, an oil painting, the paper leaf of a Mandarin fan, the paper head of a dragon kite, four Melanesian tree fern figures, burned archaeological thatch, and red-rotted leather. These examples illustrate the versatility of the ultrasonic mister on a diverse range of objects; complete treatment details are not presented. TITRE—N�bulisation Ultrasonique—Deuxi�me Partie: Applications. R�SUM�—La n�bulisation ultrasonique est une technique utile dans les cas o� il convient d'appliquer une solution par petites quantit�s, en particulier dans le but de consolider des pigments ou autres substances recouvrant un objet en fine couche. L'�quipement n�cessaire est peu on�reux et facile � monter. La m�thode d'utilisation est simple, mais parfois assez laborieuse, car plusieurs applications de solution relativement peu concentr�e sont souvent requises pour obtenir de bons r�sultats. Le n�bulisateur ultrasonique a pour principal avantage de permettre un contr�le pr�cis de la quantit� appliqu�e, de la vitesse, et de la zone couverte par le produit, ce qui est essentiel lorsqu'on traite des objets tr�s fragiles. Cet article d�crit le mat�riel ainsi que les consolidants les plus couramment utilis�s. Les auteurs d�montrent la grande vari�t� des utilisations possibles du n�bulisateur ultrasonique � l'aide de plusieurs exemples d'objets trait�s: le cadran en papier d'une boussole en mica; deux dessins au fusain; un dessin � l'encre et � l'aquarelle; une gouache; un dessin au pastel et � la gouache; une peinture � l'huile; une feuille d'�ventail mandarin en papier m�ch�; la t�te en papier d'un cerf-volant en forme de dragon; quatre sculptures m�lan�siennes en bois de foug�re arborescente; un �chantillon arch�ologique de toiture en chaume br�l� et une pi�ce de cuir partiellement d�sagr�g�e attaqu� par le “pourriture rouge.” L'article n'entre pas dans le d�tail complet des traitements. TITULO—Nebulizaci�n por ultrasonido. Segunda parte. Utilizaci�n en tratamientos. RESUMEN—La nebulizaci�n por ultrasonido es una t�cnica �til para la aplicaci�n de peque�as cantidades de soluciones diluidas a artefactos u obras de arte, particularmente para la consolidaci�n de pigmentos u otras capas delgadas en varios tipos de objetos y obras de arte. El equipo es econ�mico y f�cil de armar. El m�todo de aplicaci�n es directo, sin embargo puede ser laborioso debido a que pueden ser necesarias varias aplicaciones de soluciones en concentraciones relativamente bajas para lograr buenos resultados. La ventaja principal del nebulizador por ultrasonido esta en que ofrece un medio de controlar muy de cerca la cantidad, la velocidad, y la localizaci�n de la soluci�n aplicada, lo 1 INTRODUCTIONUltrasonic misting is a technique for applying conservation solutions to objects. Initially developed at the Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) for the consolidation of powdery pigments on ethnographic objects, it has since been modified and used on a broad range of objects for a variety of treatment applications. Compared to other methods of applying conservation solutions—such as by brush, drop, or spray—ultrasonic misting imparts much less physical impact onto the fragile surface under treatment, thus reducing potential for smearing. Misting also allows the conservator to apply smaller quantities of dilute solution in a more localized manner, thus reducing the risk of delivering excessive quantities of solution, which may cause color change or gloss. 2 EQUIPMENT, SETUP, METHOD, AND MISTING SOLUTIONSThe setup of the ultrasonic mister equipment is uncomplicated (see fig. 1, which also contains troubleshooting tips). Modifications to this basic setup, such as the addition of a small solution input hole in the shoulder of the bottle or an air input assemblage to improve the mist via air circulation, have been found to be effective (Michalski et al., forthcoming). The original mister incorporated a local extraction system over the handpiece to draw away overspray mist that might deposit on areas adjacent to the treated area (Michalski et al. forthcoming); however, the compact reducer-connector nozzle handpiece is in practice more manageable and popular (fig. 2). For the treatment of paper objects, the suction table is often used in conjunction with the mister because it aids in the containment and drying of the misting solution and reduces the risk of surface deformation during treatment.

The method of applying the ultrasonic mist differs from spraying in that the nozzle is kept stationary over the object as the solution wets and penetrates the powdery layer. Only when the area is fully saturated with consolidant solution, but just before it starts to flood, is the nozzle moved to the next area to be treated. In practice, this means that the nozzle is moved very slowly across the area being treated. During wetting of the paint layer, darkening will usually occur because of the optical changes due to the presence of solvent. This darkening usually disappears after drying, but a spot test prior to the treatment is recommended. Full wetting and saturation are important because the consolidant must penetrate the paint layer down to the substrate; otherwise, only partial consolidation may occur. Treatment strategy using the ultrasonic mister usually involves successive applications of a solution of dilute concentration. The consolidant is allowed to dry, and color change, gloss, and adhesion are monitored between each application. Only nonviscous solutions can be misted. Solutions that are known to mist are listed in table 1. TABLE 1 SOLUTIONS KNOWN TO MIST One drawback to the delivery of consolidant with the mister is that mist may deposit on the walls of the tubing or the nozzle and form a drop, which can inadvertently land on the object and cause a stain or disturb the position of

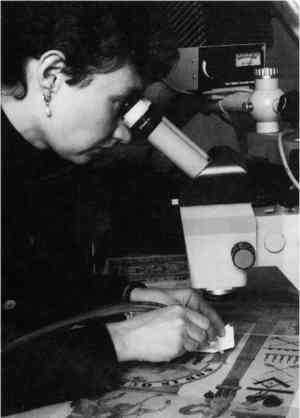

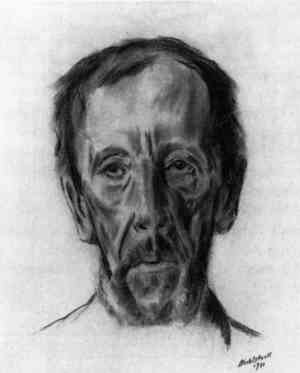

When using misting solutions containing organic solvents, it may be safer to use tubing that resists solvent extraction, such as platinum-cured silicone tubing (Williams 1995). While there is no possibility of the mist becoming contaminated with extractables from the tubing, the droplets that deposit on the tubing walls may become contaminated. 3 HEALTH CONSIDERATIONSMisting, even of aqueous solutions, should be done with the appropriate safety equipment, such as a respirator, extraction system, or a fume hood. The inhalation of small droplets of adhesive or solvent may contribute to serious health problems. 4 TREATMENT APPLICATIONSThe artifact treatments outlined here have been chosen to demonstrate the versatility and potential of ultrasonic misting in conservation. Because the following descriptions focus on the use of the ultrasonic mister, complete treatment details, such as research and spot tests usually undertaken by a conservator when selecting a consolidant, are not presented. The criteria for and process of selecting a consolidant are thoroughly discussed elsewhere in the conservation literature. 4.1 PAPER GAUGE OF A MICA COMPASSThe ultrasonic mister was successfully used at the Canadian Conservation Institute to consolidate and resize the fragile paper gauge of a mica compass belonging to the Yukon Tourism Heritage Branch (Guild et al. 1994). The three paper fragments that formed the gauge of the compass had separated from the mica base. The paper was extremely fragile, crumpled, dirty, and discolored, with scattered rust brown stains. The black ink medium marking directional signs was severely abraded and was flaking in some areas. Because the flaking ink and the surface of the soft, pulpy paper fragments could not withstand the mechanical disturbance of brushing or pneumatic spraying, the consolidant was applied as a very fine mist using the ultrasonic mister with the small reducer-connector nozzle and the paper suction table. The paper was first humidified and then consolidated overall using an aqueous solution of 0.25% Methocel A4C. It was misted three times on the recto and three times on the verso. The first two mistings of methyl cellulose penetrated the paper, which was held under very light suction. The final application formed a relatively discrete layer on the paper surface, acting as a resizing. Ultrasonic misting allowed the consolidant to be applied in a controlled and gradual manner, using successive applications of consolidant until the desired effect was achieved. Large flakes of paper still required local consolidation; for this, a 0.5% solution of Methocel A4C was applied with a fine brush under the binocular microscope. After consolidation and resizing, the paper felt much stronger and areas of flaking were adhered. 4.2 CHARCOAL DRAWING, HEAD OF AN OLD MANA charcoal drawing from the Winnipeg Art Gallery, Head of an Old Man, by Louis Muhlstock, was treated at CCI with the ultrasonic mister for removal of a discolored fixative layer (Guild et al. 1994). The spray fixative, identified as rosin, had been applied in a relatively even coating over the image. The fixative had discolored to a golden ochre color and had become dry and brittle (fig. 3). Dry mechanical testing of the charcoal indicated that it was stable and not easily transferred or smudged. Nonetheless, when subjected to droplets from a brush or spray, the medium was easily displaced.

Tests executed with the ultrasonic mister with the object on the suction table proved to be very successful, dissolving the rosin and pulling it into the blotter below without disturbing the charcoal. With the drawing placed on the suction table, the fixative and associated discoloration were reduced by misting with a 1:1 solution of ethanol and water; only small sections of the drawing were worked at a time (fig. 4). The mist was applied in successive applications, allowing the paper to dry between each and frequently replacing the blotter below. Nonimage areas were treated with the same solution by brush. By incorporating the use of the paper suction

4.3 CHARCOAL DRAWING, KARSH PORTRAITThe ultrasonic mister was employed to wash, bleach, and rinse a harsh matburn stain from a friable charcoal drawing, Karsh Portrait (artist unknown, ca. 1980) (McWilliams 1994). The stain was first reduced locally on the suction table by washing with an alkaline water mist. Bleaching was carried out with a mist of a 1.5% sodium borohydride bleach in ethanol, and finally the drawing was rinsed with an ethanol mist. Successive applications of the misting solutions were required to reduce the disfiguring stain. By introducing the solutions in a mist, there was little disturbance of the charcoal, and the discoloration was safely and easily removed. 4.4 INK DRAWING WITH WATERCOLORA primitive drawing, William III, Prince of Orange, The Glorious Immortal (artist and date unknown) from the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, executed in ink and watercolor, with areas of loose, powdery pigment and cupped, flaking paint, was consolidated with the ultrasonic mister at CCI (Guild et al. 1994). Before consolidation, the paper support was washed overall using ultrasonic humidification and wet blotters on the suction table; a significant

4.5 GOUACHE PAINTING, BLACK SUNA severely flaking and deformed gouache painting from the National Gallery of Canada (NGC), Black Sun by Michael Snow (1954) was successfully consolidated with the ultrasonic mister (Maheux and McWilliams 1995). The painting was composed of multiple layers of gouache of suspect quality applied to a hard-surfaced machine-made wove paper. Examination in raking light confirmed that the sheet had been rolled and subsequently flattened. The paint had cracked and flaked along the vertical creases, leaving a crumbled layer of detached particles as well as larger areas of complete loss. Examination of detached paint samples with polarized light microscopy revealed that the bonding of the paint layers had failed, probably resulting from the application of incompatible paints. Based on experiments with different consolidants on a series of mock-ups, gelatin was chosen for consolidating the painting. To ensure freshness, a 1% solution of 100 bloom gelatin was freshly prepared for each consolidation session. (Bloom is a measurement of the gel strength of a solution.) Before each session, the painting was placed in a humidity chamber for 4 to 6 hours. Supported on a sheet of Hollytex, it was then transferred to the suction table for misting. A microspatula was sometimes used to gently secure large particles during or after misting to ensure intimate bonding. After each session, consolidated areas were examined under the microscope. A few larger particles of gouache had to be further consolidated with a higher concentration of 2% gelatin applied with a fine brush. Following misting sessions, the work was left face up with light weight along the perimeter. The vertical deformations and undulations disappeared almost entirely after the first session on the suction table and did not recur. 4.6 PASTEL AND GOUACHE DRAWING, SUNSET AT THUNDER BAYThe mister was used to consolidate a pastel and gouache drawing on paper, Sunset at Thunder Bay (1869) by William Armstrong, at the National Archives of Canada (Hill 1995). The poor bond between the gouache and the underlying pastel layer had resulted in flaking and loss. These areas were consolidated by misting on the suction table up to four times with an aqueous solution of 1% gelatin. By incrementally applying the dilute consolidant, the possibility of causing color change was reduced. 4.7 OIL PAINTING, GLACIERAn oil painting on canvas, Glacier (1928) by Arthur Lismer, from the Art Gallery of Hamilton, was treated at the National Gallery of Canada with the ultrasonic mister for the removal of a brittle, discolored water soluble adhesive from its surface (Ruggles 1995). Iodine staining tests (Browning 1977, 90–91) confirmed that the adhesive was starch-based. It is likely that the residues were from a facing adhesive that was incompletely removed. Remnants of thin paper embedded in the starch adhesive layer support this speculation. The fabric support had previously been lined with an aqueous-based adhesive and a cotton fabric. Although the lined fabric support was stable, the paint layer exhibited extensive microscopic cupping, cracking, and flaking in areas associated with the starch adhesive residue. The paint had literally been pulled up with the swelling and shrinking of the adhesive layer as it responded to fluctuations of relative humidity. The bond between the surface adhesive residue and the paint layer was stronger than the cohesive bonding of the paint. Although the residual adhesive had no wet strength, tests indicated that it could not be removed from the surface by conventional mechanical methods employing a damp swab without extensive paint loss. The ultrasonic mister was used to relax, clean, and consolidate the painting. Under a binocular microscope, areas of adhesive residue were first gently humidified with the ultrasonic mister, thus relaxing the cupped paint. Humidified areas were covered with release paper and blotters and placed under soft weights overnight. The humidification served generally to consolidate the paint, possibly by reactivating and redistributing the starch adhesive. A few isolated areas of more pronounced cupping were consolidated with dilute parchment size, which was applied by brush. In both cases, the humidified and consolidated areas were flattened under light weight. Flattened areas were misted with water a second time to solubilize the bond between the superficial adhesive residue and the paint. The swelled adhesive was prodded off the surface with a sharpened wooden swab stick, and the paint layer was cleaned with a cotton swab dampened with distilled water. The area was again covered with release paper, blotter, and weights overnight. Application of moisture with the ultrasonic mister ensured that there was no paint loss during the removal of the adhesive and facing tissue residue. 4.8 PAPER LEAF OF A MANDARIN FANA Mandarin fan, also known as an applied figure fan, from the Ross Memorial Museum in Nova Scotia, was consolidated with the ultrasonic mister at CCI (Dicus 1994). The paper leaf of the fan, which was detached from the carved ivory skeleton, was composed of a complex painted design in gouache on Japanese paper. The gouache on the paper leaf was abraded in areas with losses. Numerous small areas with powdery or flaking paint were evident (figs. 8, 9).

Due to the visual complexity of the design and because only some areas required consolidation, areas in need of consolidation (either powdery or flaking) were identified under a binocular microscope and their location recorded on Mylar over an enlarged photograph. An aqueous solution of 0.25% Methocel A4C applied with the ultrasonic mister proved successful for powdery areas. Two to three applications of the consolidant were required before there was adequate adhesion of the pigment. Insecure flakes of gouache were consolidated, by brush, with an aqueous solution of 0.5% Methocel A4C. 4.9 PAPER HEAD OF A DRAGON KITEThe head of an oriental bamboo and paper kite in the shape of a dragon from the Alexander Graham Bell Collection in Nova Scotia was consolidated using the ultrasonic mister at Parks Canada–Atlantic Region laboratories (Boyer 1995). The head, made of Japanese paper, was painted blue overall and decorated with dots of

The flaking white dots were secured with wheat starch paste, while the powdery blue paint was consolidated by misting several applications of 0.5% gelatin in distilled water. The treatment was terminated when a slight color change was noted in a test area. Although the paint was still not strongly attached after treatment, it had now become secure enough to withstand gentle contact with soft storage materials. 4.10 MELANESIAN TREE FERN FIGURESFour carved tree fern figures from Ambrym Island, Melanesia, were treated using the ultrasonic mister at the Glenbow Museum in Calgary (Humphrey 1995). The figures, carved from the trunks of tree ferns, were covered with mud, probably composed of slaked lime and volcanic ash, and decorated with white and pink pigments (fig. 11). The mud and paint were fragile and flaking; two of the figures had already suffered a loss of 50% of their coating.

After testing several adhesives and comparing the effects of misting and airbrush spraying, it was decided to mist the flaking mud and paint with up to three applications of Rhoplex AC-33 acrylic dispersion diluted to 5% of the stock solution in water. Analysis of the paint had revealed the presence of calcium carbonate as one of the major components. Consolidation of this pigment was studied by Michalski and Dignard (1997) and gave good results with Rhoplex AC-33. Although consolidation caused a slight darkening in some areas, this color was regarded as acceptable, considering the overall improvement in bonding. 4.11 BURNED ARCHAEOLOGICAL THATCHAn extremely fragile and powdery sample of burned thatch roofing consisting of loose pieces of sea grass, recovered from the former Acadian site of Belleisle in southern Nova Scotia, was treated with the mister at Parks Canada–Atlantic Region laboratories (Day 1995). The thatch could not be touched with a brush without causing damage. The ultrasonic mister was modified for this treatment, so that the mist was

4.12 RED-ROTTED LEATHERAs with the example in section 4.11, a modified version of the mister has also been used at the CCI to apply a retanning solution to a fragile, powdery, red-rotted, vegetable-tanned leather (Barclay 1995). The leather covered an air-delivery pipe of an 1830 pipe organ. A mist of 5% aluminum isopropoxide in 1,1,1 trichloroethane was continuously pumped for 17 hours into a glass chamber, where the leather was suspended on a rack. In comparison, tests had shown that brush application displaced particles of the red-rotted surface and that eyedropper application could cause staining. 4.13 OTHER TREATMENTSNumerous ethnographic and folk art artifacts at the Canadian Museum of Civilization have been treated with the ultrasonic mister in preparation for display (B�rub� and Segal 1996). The mister was used on very powdery painted surfaces where traditional paint consolidation techniques were not suitable. It was found in these cases that misting is a useful treatment option but that it does have it drawbacks; for example, it does not always achieve complete consolidation of the painted surface and, like other consolidation methods, can result in staining of the wooden substrate. Descriptions of the use of the ultrasonic mister to treat an Egyptian coffin end piece and a Pennsylvania German low post bed (Michalski et al. forthcoming), as well as a cracked and flaking gouache painting (Weidner 1993), have been published elsewhere. 5 TREATMENT LIMITATIONS AND POTENTIALAlthough valuable for the consolidation of particles and tiny flakes, the mister, as expected, has been found to be less successful for the consolidation of large flakes of paint for several possible reasons. First, the mist cannot be focused narrowly enough to allow delivery of consolidant into cracks only; a brush can be more successful for this situation. Second, the mister delivers small quantities of dilute consolidant, but flakes often require larger quantities of consolidant at higher concentrations to bridge the gap between flake and substrate. Furthermore, even with a very slow mist velocity, it may be difficult to avoid dislodging flakes. If flakes are powdery, they can be delicately misted with a small nozzle to make them less powdery before being repositioned and fixed to the substrate by other means. Another limitation of the mister technique is that it is slow. For example, it took 40 hours to set up the mister equipment and do the consolidation for the ink drawing (section 4.4). The ultrasonic mister is valuable for the treatment of objects considered too sensitive to be treated with “normal” quantities of solvents or moisture or too delicate to be subjected to mechanical action or spraying. The mister is also useful when small local applications are required. For example, it is expected that the mister could be used to apply solvents, bleaching solutions, or cleaning solutions locally to reduce or remove stains or discoloration, to apply a coating or reform an existing layer such as a bloomed varnish, to achieve local humidification and reformation of deformed surfaces, and to aid in the removal of degrading or potentially damaging attachments such as tapes, hinges, and adhesive residues. Because the mister delivers small quantities of solution, it may help prevent localized overcleaning, which can occur if the solvent selected to remove problematic materials also removes the degradation products in the paper support, creating a lighter area. 6 CONCLUSIONSThe ultrasonic mister is a versatile tool for the application of dilute solutions to works of art and artifacts, in particular for the consolidation of flaking and powdery paints on surfaces. The apparatus is economical and easily assembled, and the method of application is straightforward, although it can be labor-intensive because several applications of a relatively low concentration of solution may be required to achieve good results. The ultrasonic mister's main advantage is that it offers a means of finely controlling the quantity, velocity, and location of the solution delivered, advantages that are most useful when treating very fragile surfaces. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe authors thank Stefan Michalski of the Canadian Conservation Institute for his valuable suggestions and advice. The authors also thank the following individuals who have shared their experience with the ultrasonic mister: Bob Barclay and Carl Bigras of the Canadian Conservation Institute; Ghislain B�rub�, Martha Segal, and Caroline Marchand of the Canadian Museum of Civilization; Greg Hill of the National Archives of Canada; Anne Ruggles of the National Gallery of Canada; Colleen Day and Candace Boyer of Parks Canada, Historic Resource Conservation–Atlantic Region; Heather Dumka of the Glenbow Museum; Lori Van Handel of Williamstown Art Conservation Center; David Arnold of Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; Alexandra H�ttin of the Fachhochschule, Cologne; Donald Humphrey, private conservator, Calgary, Alberta; Diana Dicus, private conservator, Boise, Idaho; and Peter Newlands, private conservator, Ottawa, Ontario. SOURCES OF MATERIALSUltrasonic humidifier,local hardware and drug stores C-Flex platinum-cured silicone tubing, clear flexible PVC tubing, low-density polyethylene bottle, high-density polyethylene reducer-connectors, T-piece, plastic suppliers such as:Cole-Parmer Instrument, Vernon Hills, Ill. 60061 Small screw-down hose clamp scientific supply houses such as:Fisher Scientific, 112 Colonnade Rd., Nepean, Ontario K2E 7L6, Canada REFERENCESBarclay, R.1995. Personal communication. Canadian Conservation Institute, 1030 Innes Rd., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. B�rub�, G., and M.Segal. 1996. Personal communication. Canadian Museum of Civilization, Hull, Quebec, Canada. Boyer, C.1995. Personal communication. Parks Canada, Historic Resource Conservation–Atlantic Region, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada. Browning, B.L.1977. Analysis of paper. New York: Marcel Dekker. 90–91. Day, C.1995. Personal communication. Parks Canada, Historic Resource Conservation–Atlantic Region, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada. Dicus, D.1994. Personal communication. Canadian Conservation Institute, 1030 Innes Rd., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Guild, S., R.Douglas, and W.McWilliams. 1994. Use of the ultrasonic mister in paper conservation. Paper presented at the International Institute for Conservation–Canadian Group 20th Annual Conference, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Hill, G.1995. Personal communication. National Archives of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Humphrey, D.1995. Care and consolidation of four Melanesian carved ceremonial figures by ultrasonic mist. Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Maheux, A., and W.McWilliams. 1995. The use of the ultrasonic mister for the consolidation of a flaking gouache painting on paper. Book and Paper Group annual14. Washington, D.C.:AIC. 19–25. McWilliams, W.1994. Personal communication. National Archives of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Michalski, S., and C.Dignard. 1997. Ultrasonic misting. Part 1, Experiments on appearance change and improvement in bonding. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation36:109–26. Michalski, S., C.Dignard, L.van Handel, and D.Arnold. Forthcoming. Ultrasonic mister: Application to consolidation treatments of powdery paint on wooden artifacts. In Painted wood: History and conservation. Proceedings of the symposium in Williamsburg, Va., September 11–14, 1994. Ruggles, A.1995. Personal communication. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Weidner, M. K.1993. Treatment of water-sensitive and friable media using suction and ultrasonic mist. Book and Paper Group annual12. Washington, D.C.:AIC. 75–84.

Williams, S.1995. Analysis of C-Flex tubing. Conservation processes research report577. Ottawa: Canadian Conservation Institute. AUTHOR INFORMATIONCAROLE DIGNARD graduated from the University of Ottawa with a B.Sc. in physics and Italian in 1981 and an honors B.A. in classical studies in 1983. She received a master's degree in art conservation from Queen's University in 1986, specializing in objects. In 1987, she was a J. Paul Getty Fellow at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Harvard University. She has been working in the ethnology/objects section of the Canadian Conservation Institute since 1988. Address: Canadian Conservation Institute, 1030 Innes Rd., Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0M5, Canada. ROBYN DOUGLAS graduated from Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, with a master's degree in art conservation in 1992. She completed fellowships at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and at the Canadian Conservation Institute. Currently she is the paper conservator at the Glenbow Museum. Address: Glenbow Museum, 130 9th Ave. SE, Calgary, Alberta T2N 0A5, Canada. SHERRY GUILD graduated from the art conservation techniques program at Sir Sandford Fleming College in Peterborough, Ontario, in 1984. Since that time she has worked in the Works on Paper Laboratory at the Canadian Conservation Institute. Address: Canadian Conservation Institute, 1030 Innes Rd., Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0M5, Canada. ANNE F. MAHEUX graduated from the University of Guelph, Ontario, in 1979 with an honors B.A. in fine art and received a master's in art conservation from Queen's University in 1981. She received a certificate in the conservation of works on paper, Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, in 1982. She has been working as a conservator of graphic art at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, since 1982. She was made a Fellow of the American Academy in Rome in 1996. Address: National Gallery of Canada, 380 Sussex Dr., P.O. Box 427, Station A, Ottawa, Ontario, K1N 9N4, Canada. WANDA McWILLIAMS graduated from the Ontario College of Art in Toronto, Ontario, in 1982 and from the art conservation techniques program at Sir Sandford Fleming College in Peterborough, Ontario, in 1986. She was a Fellow at the Canadian Conservation Institute in 1987 and a Getty intern at the National Gallery of Canada in 1995. Currently she is a paper conservator in private practice in Ottawa. Address: P.O. Box 6, Navan, Ontario, K4B 1J3, Canada.

Section Index Section Index |