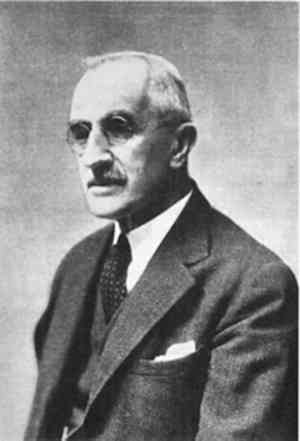

ALFRED LUCAS: EGYPT'S SHERLOCK HOLMESMARK GILBERG

ABSTRACT—A biography of the British Egyptologist Alfred Lucas (1867–1945) is given, including a detailed discussion of his most important scientific achievements, such as the rediscovery of the formula for faience and the publication of the landmark study Ancient Egyptian Materials. This paper places particular emphasis on the impact his work had upon the development of archaeological conservation as a profession. TITRE—Alfred Lucas: Le Sherlock Holmes de l'Egypte. R�SUM�—Cet article donne une biographie de l'�gyptologue britannique Alfred Lucas (1867–1945), ainsi qu'un compte rendu d�taill� de ses plus importantes r�alisations scientifiques, telles que la red�couverte de la formule de la fa�ence ainsi que la publication de sa magistrale �tude “Ancient Egyptian Materials.” L'accent est mis plus particuli�rement sur l'impact de son travail sur le d�veloppement de la profession de restaurateur en arch�ologie. TITULO—Alfred Lucas: El Sherlock Holmes de Egipto. RESUMEN——Se presenta una biograf�a del egipt�logo brit�nico Alfred Lucas (1867–1945), incluyendo una descripci�n detallada de sus logros cient�ficos mas importantes, tales como el redescubrimiento de la formula para cer�mica de faenza y la publicaci�n de su estudio magistral: “Materiales Egipcios Antiguos.” Este trabajo enfatiza especialmente el impacto que su trabajo tuvo en el desarrollo de la conservaci�n arqueol�gica como profesi�n. 1 INTRODUCTIONIn recent years, practicing conservators have expressed considerable interest in the history of conservation. As the discipline of materials conservation matures, it is natural that conservators seek to understand the origins of their profession. Unfortunately, only a few writers have published on this subject, particularly in the area of archaeology (Caldararo 1987; Gilberg 1987; Seeley 1987; Johnson 1993). To date, most of what we know about early developments in archaeological conservation may be derived from the published works of only a handful of individuals. These authors include Albert Voss, curator at the Museum of Mankind in Berlin (Gummel 1938); Friedrich Rathgen, director of the Chemical Laboratory of the Royal Museums of Berlin (Otto 1979); O. A. Rhousopoulos, chemist at the National Museum in Athens (Bobolines and Bobolines 1958–62); Gustav Rosenberg, conservator at the National Museum in Denmark (Thomsen 1940); Alexander Scott, director of the first chemical laboratory at the British Museum (Robertson 1947); H. J. Plenderleith, assistant keeper at the British Museum Laboratory (Plenderleith 1934); Flinders Petrie, British Egyptologist (Drower 1985); and Alfred Lucas, chemist at the Cairo Museum. Their works laid the groundwork for many of the most important developments in the field of archaeological conservation and had a profound impact upon the establishment of materials conservation as a profession. Of the above, Alfred Lucas was the quintessential conservation scientist. An analytical chemist by training with a strong background in forensic science, Lucas was ideally suited to elucidate The following biography emphasizes some of Lucas's most important scientific achievements and their impact upon the development of archaeological conservation as a profession. 2 THE LABORATORY OF THE GOVERNMENT CHEMISTSurprisingly little is known of Lucas's personal life. Much of what we do know derives from a handful of obituaries published soon after his death by several of his colleagues and close friends (Englebach 1945; Hurst 1945–46; Antiquities Journal 1946; Ball et al. 1946; Plenderleith 1946; Coremans 1946–47; Brunton 1947). They show he was born on August 27, 1867, in Charlton-upon-Medlock, Lancaster County, England. His father was listed as a commercial traveler or salesman. Lucas attended private schools in Manchester. In August 1891, after passing the entrance examinations in chemistry, physics, and mathematics, Lucas was appointed a student in the Inland Revenue Laboratory (Hammond 1993). At the time, all students were also required to attend a two-year course at the Royal School of Science (now known as Imperial College). Lucas successfully completed the course and in April 1893 was appointed temporary assistant. The Inland Revenue Laboratory later became the Laboratory of the Government Chemist, which recently celebrated its 150th anniversary with the publication of a comprehensive history of its work (Hammond and Egan 1992). The laboratory was initially formed for the purpose of analyzing the alcohol content of beer and wine imported into England to establish the required custom duties. Over the years, the laboratory's responsibilities were expanded to include the analysis of a wide variety of commercial products. The government chemists worked long hours, generally six days a week, performing tedious chemical analysis without the aid of modern analytical instrumentation. No doubt it was here that Lucas perfected his analytical skills, which were to serve him so well years later in Egypt.

3 EGYPT AND THE GOVERNMENT ANALYTICAL LABORATORIESIn 1897 Lucas was placed on extended leave from the civil service after he contracted tuberculosis. A year later he left for Egypt, where he made a complete recovery. Lucas probably chose Egypt as his destination for health reasons, though opportunities for advancement for a young, aspiring civil servant were certainly In May 1898, not long after his arrival in Cairo, Lucas joined the Salt Department, which later became the Egyptian Salt and Soda Company. Less than a year later, he accepted another position as a chemist at the Geological Survey Department under the direction of Sir Henry Lyons. There he managed a small chemical laboratory for the analysis of Egyptian minerals located in the gardens of the Public Works Ministry. This move proved most fortuitous, for it was here that Lucas undoubtedly developed his passion for Egyptology, as his duties invariably brought him into contact with ancient monuments and sites. During this time he published a number of important studies on the soils and waters of the Nile as well as the deterioration of building stones in Egypt (Lucas 1902). In 1912, with the addition of the Assay Office and a small petroleum division, this laboratory became a separate department, referred to as the Government Analytical Laboratories and Assay Office. As head of this laboratory, Lucas assisted the British military authorities on a number of important chemical matters during World War I. For his efforts he received the Order of the British Empire. Egypt subsequently awarded him the Third Order of the Nile and the Fourth Order of Osmania. As head of this new department, Lucas became somewhat of a local celebrity as an expert government witness on forensic matters. He acquired a reputation as a ballistics and handwriting expert and testified at various criminal proceedings involving firearms and forgeries. One of his colleagues described him as “not an easy witness to bully or browbeat, and his evidence was often vital for either the condemnation or acquittal of the accused” (Ball et al. 1946). The local English newspaper, the Egyptian Gazette(1923d–e), frequently reported Lucas's testimony at various criminal trials, including the so-called Great Conspiracy Trial at which he identified the poison applied to the tip of an arrow used in a murder. In a more celebrated case, Lucas calculated the trajectory of a bullet that had been accidentally fired by a British soldier from a train, killing a passenger in an adjacent compartment (Edwards 1993). Apparently the bullet deflected off some ironwork in the station before entering through the window and striking the victim. Lucas worked out mathematically where the bullet struck the ironwork and located the actual mark. Lucas's keen interest in forensic science led him to publish numerous papers on the application of chemistry to criminal investigations. In 1920 he published one of the first English texts on the subject, Legal Chemistry and Scientific Criminal Investigation. This work was expanded into what became a standard textbook on forensic chemistry (Lucas 1921). Subsequent editions frequently drew upon his experience with archaeological materials, which he often used as examples. In his discussion of the decomposition of the human body after death, Lucas frequently referred to Egyptian mummification practices. He also used Egyptian antiquities as examples to illustrate how chemical analysis could be used to establish the authenticity of an antique. Lucas's forensic work drew critical acclaim both at home and abroad. He received high praise from the eminent medical-legal expert C. A. Mitchell, editor of the Analyst(Mitchell 1920). Excerpts from his book even appeared in the Egyptian Gazette(1922a–e), which referred to him as “the Sherlock Holmes of Egypt.” He probably relished this reputation given his fondness for detective thrillers, particularly the works of Austin Freedman and John Rhode (Brunton 1947). Apparently, many of the authors were his personal friends. 4 THE CAIRO MUSEUM AND THE TOMB OF TUTANKHAMENIn March 1923, at the age of 55, Lucas retired from the civil service to pursue his interest in Egyptian archaeology. For years he had maintained a small chemical laboratory at his flat at Gresham House in Garden City (Brunton 1947). It was there, with the aid of a small electric furnace, that he was able to reproduce ancient faience, the composition of which was a matter of great dispute. Within a month of his retirement, Lucas was appointed consulting chemist to the Egyptian Department of Antiquities in Cairo, where he served in both an official and unofficial capacity until his death in 1945. In 1932 his contract was not renewed though he remained at the museum working as a volunteer until December 1934 when, once again, he was given official status with a small salary. Lucas was fascinated with the technical achievements of the ancient Egyptians. Over the years he published the results of numerous studies describing the composition and method of manufacture of a range of ancient Egyptian materials. These studies eventually culminated in the publication of the first comprehensive treatise on the subject, entitled Ancient Egyptian Materials(Lucas 1926). First published in 1926 and later extensively revised in successive editions, it grew to become a standard textbook, laying the groundwork for many of the most important advances in Egyptology (Stoley 1927; Plenderleith 1935). The significance of this work cannot be overestimated. At the time of its publication, few archaeometric studies of ancient Egyptian materials had been conducted with any degree of rigor, and inferences were often made based on incomplete or inconclusive evidence. Lucas brought a muchneeded sense of objectivity to the study of ancient Egyptian materials and succeeded in dispelling a number of prevailing myths or misconceptions, particularly with regard to the true nature of Egyptian faience and the materials used in Egyptian mummification, as well as the use of antimony. The purported use of antimony by the ancient Egyptians was particularly controversial. Antimony plating in Egypt had been reported in the literature by Fink and Kopp (1933), who described several copper objects possessing scattered surface spots that they identified as metallic antimony. Lucas disputed their findings and suggested that the presence of the metallic antimony was more likely the result of the electrolytic reduction process used to clean the objects (Lucas and Harris 1989). Antimony, according to Lucas, was not an uncommon impurity in ancient Egyptian copper objects, and electrolytic reduction may have brought about the reduction of antimony corrosion products to the metallic state, thus producing the appearance of plating. Lucas's work, however, was not always welcomed by the archaeological community. Neither an archaeologist nor a historian by training, Lucas was considered an interloper by some, though most archaeologists respected and admired his contributions. Some of these criticisms were warranted. His published works frequently lacked adequate descriptions of the tests and procedures he used to analyze Egyptian antiquities, while many of his reference citations were incomplete. Not long after his arrival at the Cairo Museum, Howard Carter approached Lucas to assist him in the scientific examination and preservation of the antiquities excavated from the tomb of Tutankhamen (Carter and Mace 1927–33; James 1992). Carter was indeed fortunate to secure the services of Lucas, given his reputation as an experienced chemist with an interest in archaeology. Lucas proved to be one of Carter's most loyal and dedicated supporters and served him well throughout many seasons of excavation. Though the motives and intentions of many of the individuals associated with the excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamen were often called into question, Lucas's were always beyond reproach. In a recent historical account of the excavation of the tomb, Lucas was portrayed as probably the only truly honest person

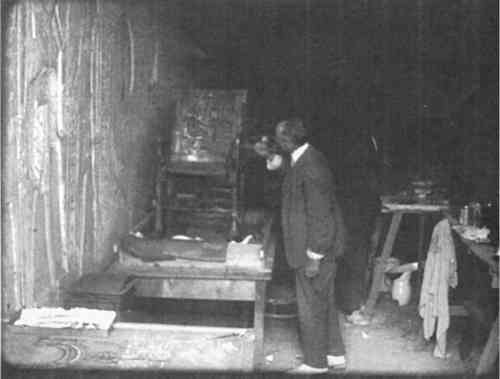

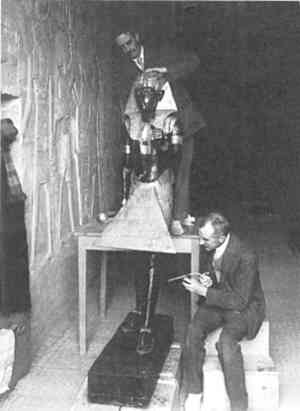

Lucas, along with the talented young archaeologist Arthur Mace (Lee 1992), who had a reputation as a skilled excavator and restorer, established a makeshift laboratory in the empty tomb of Seti II located directly opposite the opening of Tutankhamen's tomb. The antiquities were temporarily transferred there for preliminary treatment prior to the more arduous journey to the Cairo Museum. After treatment and packing, the artifacts were transported by camel or mule to the Nile some six miles away, where they were then loaded onto a steamer for Cairo. Conditions in the tomb were difficult to say the least. In cramped and extremely hot quarters, Lucas and Mace labored long hours trying to keep pace with the antiquities as the tomb was cleared of its contents. Highly descriptive accounts of day-to-day life in this conservation laboratory were published in many popular newspapers (Egyptian Gazette 1923a–c; New York Times 1923a–d; Times [London] 1923a–g). A number of these newspapers included interviews with Lucas, who proved a strong advocate for preservation. In his own right, he did much to popularize conservation by drawing the public's attention to many behind-the-scene activities. In the following

Many of the objects are in such a condition that before they are photographed, recorded, packed, or transported to Cairo they must be cleaned, strengthened and repaired. Any error in treatment might ruin them, and would probably be irreparable. Thus, some of the articles are of wood covered with plaster (gesso), which in turn is gilt or painted, and also frequently ornamented with coloured inlay. How is such an object to be treated? Manifestly, the first thing to do is to remove superficial dust, which may usually be done by means of a small pair of bellows or by gentle brushing with an artist's small, soft, dry bristle. A duster cannot be used, as this might catch in any loose gold and cause damage. After removing the loose dust, although there is considerable improvement in the appearance, neither the gold (or paint) nor inlay is yet bright and clean. At this stage it frequently seems probable that treatment with water might be helpful, but before water is used it must be known whether it will cause any injury. What will be the effect of water on the dry wood, what on the gilt or paint, what on the gesso, what on the inlay, and what on the cementing material? Before these questions can be answered the nature and properties of all these materials must be analyzed. The nature of the materials must also be known before the object can be correctly described. What, for example, is the composition of the coloured inlay? Is it glass, faience, or stone? Very little chemical work has been done on many of the problems mentioned, and of that little a considerable proportion of the results are so scattered in scientific journals that they cannot easily be traced. Frequently, too, the chemist has not been in sufficiently intimate contact with the archaeological side of the question and, therefore, from the results of a single analysis of a small fragment of a specimen, about which he knows little or nothing, he refrains from giving a definite opinion. At this point, too, other chemical problems present themselves. For instance, what are the nature and cause of the strongly adherent amorphous coating frequently found on faience inlay or the white coating on faience vessels? From the reply to these questions the nature of the chemical changes that have taken place may be deduced and so methods of cure may be devised. A chemical analysis, therefore, of all surface incrustations or deposits is essential. Again, what is the composition of the various cementing materials originally used? How was the gesso made to adhere to wood or gold fastened to gesso? What cement was used for inlay on gesso and for inlay on jewelry, respectively? What is the best cementing material for refastening loose gold or loose inlay, since a material employed by the Ancient Egyptians in the dry climate of Upper Egypt is not necessarily suitable for the damper climate of museums? Lucas and Mace developed an impressive system of documenting the condition and treatment applied to the individual objects using cross-referenced index cards that can still be found in the Griffith Institute at Oxford (McLean and McDonnell 1992). Treatment was minimal. Objects were cleaned of dirt using soft bristle brushes and bellows and, if necessary, strengthened by impregnation with paraffin or beeswax, or celluloid (cellulose nitrate) dissolved

Altogether, Lucas worked nine full seasons at Luxor. The remainder of his time was spent in Cairo performing chemical analysis and preparing objects for exhibition. During the summer months he traveled to England to visit family and consult with colleagues at the British Museum, where he was already a legendary figure known as “Tutankhamen's doctor” (Edwards 1993). Throughout his life Lucas remained intimately involved with the care and preservation of the antiquities excavated from Tutankhamen's tomb. He even assisted in their packing and unpacking when the objects were moved from the museum during World War II as a safeguard against bombing by the Italians. Without a doubt, the survival of many of these antiquities can be attributed to his singular efforts. One event, in particular, epitomizes Lucas's devotion. When the British Broadcasting Company wanted to record the sound of one of Tutankhamen's silver trumpets, a musician from the army unit in the Kasr el-Nil barracks was asked to come to the Cairo Museum to play it the night before the broadcast (Edwards 1993). When no one was looking, he slipped a mouthpiece In 1924 Lucas published his most definitive work on the preservation of archaeological artifacts. Antiquities: Their Restoration and Preservation drew heavily upon his experience with the treatment of Tutankhamen's tomb (Lucas 1924). Though it contained few technical advances, it was nonetheless significant for its overall approach to the treatment of archaeological materials. Lucas's guiding philosophy was relatively simple. To preserve an object, its composition and method of manufacture must be thoroughly understood as well as the exact nature of the change or deterioration that has occurred. Moreover, the long-term impact of the proposed method must be taken into consideration when planning a treatment. To this end, Lucas foresaw the need for a much more scientific approach to the treatment of archaeological materials. At the same time he recognized the need for highly skilled craftsmen capable of undertaking the actual treatment. He believed this blending of art and science in conservation could be achieved only through the combined efforts of dedicated scientists and conservators. He wrote:

Though his most important work was associated with the tomb of Tutankhamen, Lucas provided invaluable assistance to American, English, and French excavators active in Egypt during the early 1900s. His efforts on behalf of George Reisner, in particular, did much to secure the preservation of the antiquities excavated from the Tomb of Queen Hetep-heres, the mother of Cheops (Reisner 1928, 1929, 1955). The preservation of many of the antiquities excavated by Pierre Montet from the intact burial of King Shashanq at Tanis also owes much to Lucas (Brunton 1939). Lucas's efforts on behalf of other archaeologists, however, remain poorly documented in the literature though references to his analytical work can be found throughout the published work of Engelbach (1946), Brunton (1930), and others. 5 THE WAR YEARS AND THE PRESERVATION OF THE THEBAN TOMBSDuring World War II, Lucas broadcast regularly to troops stationed in Egypt and frequently lectured at hospitals and military camps. He felt a deep affection for the soldiers and delighted in entertaining them however he could. His services were also much in demand by the military authorities, both American and British, who sought his forensic expertise in numerous court-martials. In spite of the war and failing health, Lucas remained active. In 1941 he was asked to serve on a commission to consider the restoration of the Theban tombs, which for years had suffered from vandalism, flooding, and general neglect (Lucas 1923c; Fakhry 1947a–b). Lucas was an obvious choice to be included on this commission given his knowledge of local hydrology and In one of his last official duties, Lucas demonstrated his keen sense of fair play when he drew the commission's attention to the pitiful salary paid to his Egyptian successor at the Cairo Museum (Lucas 1923c):

Sadly, Lucas died at the age of 78 while on his way to Luxor to attend a meeting of the commission to inspect the tombs. Lucas's death might have been prevented had it not been for an unlikely sequence of events (Edwards 1993). For years he had suffered from heart problems. Guy Brunton, a fellow member of the commission who was traveling with Lucas on the train, carried Lucas's heart medicine so that he could administer the drug in the event of a heart attack. For some reason they traveled on different arabiyas (cars) from the train station to the hotel in Luxor, when Lucas fell ill. Brunton arrived too late to save him. Lucas died on December 9, 1945, the lone survivor of Tutankhamen's curse (New York Times 1945). As he was a bachelor, the bulk of his estate was left to his brother, sister, and each of their children. Though his notes on the conservation of the tomb of Tutankhamen were transferred to the Griffith Institute at Oxford, little else remains other than his published works, but these are without parallel in any other branch of archaeology. In total Lucas published more than 100 books and papers, including two small booklets (Brunton 1947) entitled A Potted History of Egypt and A Potted History of Libya, which he printed at his own expense. A deeply religious man with an ardent interest in biblical archaeology, Lucas also published a littleknown work entitled The Route of the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt (1938). Lucas was clearly ahead of his time. Fortunately for Egyptology, he was the right man, in the right place, at the right moment in history. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to thank the following individuals for their kind assistance in the preparation of this paper: Francesca Piqu�e, I.A.E. Edwards, Margaret Orr, Vincent Daniels, Nigel J. Seeley, J. R. Harris, Marsha Hill, P. W. Hammond, and Nasri Skandr. APPENDIX1 APPENDIX: WORKS BY ALFRED LUCASLucas, A. 1900. Analysis of bronze and copper objects. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 1:287–88. Lucas, A. 1900. Analysis of one of the crowns found at Dahshour. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 1:286. Lucas, A. 1900. Chemical report on the phosphate: A contributing report on the phosphate in Egypt. Cairo: Egyptian Survey Department. Lucas, A. 1901. Analyse de quelques specimens de gris pris dans les colonnes de la Salle Hypostyle. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 2:177–281. Lucas, A. 1902. The disintegration of building stones in Egypt. Cairo: Geological Survey Department, Public Works Ministry. Lucas, A. 1902. Preliminary investigation of the soil and water of the Fayum province. Cairo: Geological Survey Department. Lucas, A. 1903. The salt content of some agricultural drainage waters in Egypt. Cairo Scientific Journal 2:413–17. Lucas, A. 1903. Soil and water of the Wadi Tumilat lands under reclamation. Cairo: Egyptian Survey Department. Lucas, A. 1905. Ancient Egyptian mortars. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 7:4–7. Lucas, A. 1905. The blackened rocks of the Nile cataracts and of the Egyptian deserts. Cairo: National Printing Department. Lucas, A. 1907. The physical nature of soil. Survey Notes, Cairo 10:271–76. Lucas, A. 1908. The chemistry of river Nile. Cairo: Egyptian Survey Department. Lucas, A. 1908. On a sample of varnish from the temple al Deir-el-Bahri. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 9:7. Lucas, A. 1910. Preservative materials used by the ancient Egyptians in embalming. Cairo Scientific Journal 4:66–68. Lucas, A. 1910. Preservative materials used by the ancient Egyptians in embalming. Chemical News 101: 266. Lucas, A. 1911. The salt content of some agricultural drainage waters in Egypt. Cairo Scientific Journal 5:190–91. Lucas, A. 1912. Natural soda deposits in Egypt. Cairo: Geological Survey Department. Lucas, A. 1912. Natural soda deposits in Egypt. Bulletin Imperie Institute 10:686–88. Lucas, A. 1913. The relative manurial value of Nile water and sewage. Cairo Scientific Journal 7:1–9. Lucas, A., and B.F.E. Keeling. 1913. The manufacture of the Holy Carpet. Cairo Scientific Journal 7:129–30. Lucas, A. 1914. The formation of sodium carbonate and sodium sulphate in nature. Cairo Scientific Journal 8:185–88. Lucas, A. 1914. Preservative materials used by the ancient Egyptians in embalming. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 1:244–45. Lucas, A. 1914. The question of the use of bitumen or pitch by the ancient Egyptians in mummification. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 1:241–45. Lucas, A. 1915. The disintegration and preservation of building stones in Egypt. Cairo: Geological Survey Department. Lucas, A. 1916. Alcoholic liquor and the liquor trade in Egypt. Cairo: Cairo Government Press. Lucas, A. 1917. Efflorescent salt of unusual composition. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 17:86–88. Lucas, A. 1920. Legal chemistry and scientific criminal investigation. New York: Longmans, Green and Co. Lucas, A. 1920. Report of the work of the Egyptian Lucas, A. 1921. Forensic chemistry. London: E. Arnold and Co. Lucas, A. 1922. The inks of ancient and modern Egypt. Analyst 47:9–15. Lucas, A. 1922–23. Effect of exposure on colourless glass. Cairo Scientific Journal 11:72–73. Lucas, A. 1923. The examination of firearms and projectiles in forensic cases. Analyst 48:203–10. Lucas, A. 1924. Antiquities: Their restoration and preservation. London: E. Arnold and Co. Lucas, A. 1924. Methods used in cleaning ancient bronze and silver. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 24:17. Lucas, A. 1924. Mistakes in chemical matters frequently made in archaeology. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 10:128–32. Lucas, A. 1924. Note on the cleaning of certain objects in the Cairo Museum. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 24:15–16. Lucas, A. 1924. Note on the temperature and humidity of several tombs in the valley of the tombs of the kings at Thebes. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 24:12–14. Lucas, A. 1924. The use of chemistry in archaeology. Cairo Scientific Journal 12:144–45. Lucas, A. 1926. Ancient Egyptian materials. London: Longmans, Green and Co. Lucas, A. 1926. Damage caused by salt at Karnak. Cairo Scientific Journal 51:47–54. Lucas, A. 1926. Problems in connection with ancient Egyptian materials. Analyst 51:435–50. Lucas, A. 1927. The necklace of Queen Aahhotep. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 27:69–71. Lucas, A. 1927. Notes on the early history of tin and bronze. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 14:100–101. Lucas, A. 1928. Egyptian use of beer and wines. Ancient Egypt 1–5. Lucas, A. 1929. The nature of the colour of pottery, with special reference to that of ancient Egypt. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 69:113–29. Lucas, A. 1930. Ancient Egyptian wigs. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 30:190–96. Lucas, A. 1930. Cosmetics, perfumes, and incense in ancient Egypt. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 16:41–53. Lucas, A. 1931. The canoptic vases from the tomb of Queen Tiyi. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 31:13–21. Lucas, A. 1931. Cedar-tree products employed in mummification. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 17:13–21. Lucas, A. 1932. Antiquities: Their restoration and preservation. Rev. ed. London: E. Arnold and Co. Lucas, A. 1932. Black and black-topped pottery. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 32:93–96. Lucas, A. 1932. The occurrence of natron in ancient Egypt. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 18:62–66. Lucas, A. 1933. Ancient Egyptian materials and industries about 1350 B.C. Analyst 58:654–64. Lucas, A. 1933. Appendix 2. The chemistry of the tomb. In The tomb of Tut-ankh-amen, vol. 3, ed. H. Carter and A. Mace. London: Cassell and Co. Lucas, A. 1933. Beam's colour test for hashish. Analyst 58:602. Lucas, A. 1933. Resin from a tomb of the Saite period. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 33:187–89. Lucas, A., and D. B. Harden. 1933. Ancient glass. Antiquity 7:419–29. Lucas, A. 1934. Ancient Egyptian materials . Rev. ed. London: E. Arnold and Co. Lucas, A. 1934. Ancient glass. Antiquity 8:94–95. Lucas, A. 1934. Artificial eyes in ancient Egypt. Ancient Egypt 84–89. Lucas, A. 1934. Woodworking in ancient Egypt. Empire Forestry Journal 11:213–14. Lucas, A. 1935. Ancient Egyptian materials and industries. Rev. ed. London: Longmans, Green and Co. Lucas, A. 1935. Forensic chemistry and scientific criminal investigation. Rev. ed. London: E. Arnold and Co. Lucas, A. 1935. Were the Giza Pyramids painted? Antiquity 12:26–30. Lucas, A. 1935. Review of Origins and development of applied chemistry, by J. R. Partington. Analyst 60:498–99. Lucas, A. 1935–36. Review of The preservation of antiquities, by H. J. Plenderleith. Science Progress: A Quarterly Review of Scientific Thought, Work and Affairs 30:185. Lucas, A. 1936. Glazed ware in Egypt, India and Mesopotamia. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 22:141–64. Lucas, A. 1936. The medallion of Dahshur. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 36:197–200. Lucas, A. 1936. The wood of the Third Dynasty plywood coffin from Saqqara. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 36:141–64. Lucas, A., and G. Brunton. 1936. The medallion of Dashur. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 36:141–64. Lucas, A. 1937. Notes on myrrh and stactes. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 23:27–33. Lucas, A. 1937. The wood of the Third Dynasty: Plywood coffin from Saqquara. Annales du Service des Antquites de L'�gypte 36:1–4. Lucas, A. 1938. Early Egyptian faience. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 24:198–99. Lucas, A. 1938. The ancient Egyptian Beckhen stone. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 38:127–56. Lucas, A. 1938. Inlaid eyes in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia and India. Technical Studies in the Field of Fine Arts 7:1–32. Lucas, A. 1938. Poisons in ancient Egypt. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 24:198–99. Lucas, A. 1938. The route of the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. London: Edward Arnold and Co. Lucas, A. 1939. Glass figures. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte 39:227–35; 333–34. Lucas, A. 1942. Obsidian. Annales du Service des Antiquities de L'�gypte 39:272–74. Lucas, A. 1948. Ancient Egyptian materials and industries. Rev. ed.London: E. Arnold and Co. Lucas, A., and J.R. Harris. 1989. Ancient Egyptian materials and industries. Rev. ed. London: Histories and Mysteries of Man. 2 NEWSPAPER ARTICLESLucas, A. 1923. Saving the fabrics: Some curiosities of disintegration. Times (London), February 3. Lucas, A. 1923. Tells of restoring objects: Alfred Lucas explains treatment of Tut-ankh-amen treasures. New York Times, February 7. Lucas, A. 1923. Experts at work: The triumphs of science. Times (London), February 10. Lucas, A. 1923. Luxor tomb problem: Scarlet on gold. Times (London), March 19. Lucas, A. 1923. Tomb may yield new color ideas, scarlets, yellows, pinks and grays on Tutankhamen's treasure will be analyzed, decay also to be studied, scientists will try to determine. New York Times, March 19. Lucas, A. 1923. Problems for Luxor experts: The work of preservation. Times (London), April 3. Lucas, A. 1923. Tutankhamen's tomb: Some interesting chemical problems. Times (London), April 5. REFERENCESAntiquaries Journal.1946. Alfred Lucas. Antiquaries Journal26: 231. Ball, W. L., R.Engelbach, D. S.Gracie, H. E.Hurst, and L. F.McCallum. 1946. Mr. Alfred Lucas, O.B.E. Nature3988: 433–34. Bobolines, Spyros Ant., and Konst. Ant.Bobolines, eds.1958–62. Mega Hellenikon biographikon lexikon. Athens: Ekdosis Biomechanikes Epitheireseos. 1:85–103s.v. Rhousopoulos, O. A. Brunton, G.1930. Qau and Badari III. London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt. Brunton, G.1939. Some notes on the burial of Shashanq Heqa-Kheper-re. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte39:541–47. Brunton, G.1947. Alfred Lucas, 1867–1945. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte47:1–6. Caldararo, N. L.1987. An outline history of conservation in archaeology and anthropology as presented through its publications. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation26:85–104. Carter, H., and A. C.Mace. 1927–33. The tomb of Tutankhamun.3 vols. London: Cassell and Co. Cooper, A.1989. Cairo in the war, 1939–45. London: Hamish Hamilton. Coremans, P.1946–47. Alfred Lucas. Egypte Pharaonique21:205–6, 22:301–4. Drower, M. S.1985. Flinders Petrie: A life in archaeology. London: Victor Gollancz. Edwards, I.E.S.1993. Personal communication. Curator of Egyptology (retired), British Museum. Egyptian Gazette. 1922a. Egypt's Sherlock Holmes, forensic chemistry, crime and the chemist, Mr. A. Lucas's book. Egyptian Gazette, April 10. Egyptian Gazette. 1922b. Egypt's Sherlock Holmes, forensic chemistry, Mr. A. Lucas's book, the tale of a shirt. Egyptian Gazette, April 11. Egyptian Gazette. 1922c. Egypt's Sherlock Holmes, forensic chemistry, Mr. A. Lucas's book, the hand-writing and nationality. Egyptian Gazette, April 14. Egyptian Gazette. 1922d. Egypt's Sherlock Holmes, examples of forensic chemistry, dust and dirt, explosives and explosions. Egyptian Gazette, April 27. Egyptian Gazette. 1922e. Egypt's Sherlock Holmes, forensic chemistry, Mr. A. Lucas's book, stains and marks. Egyptian Gazette, April 29.

Egyptian Gazette. 1923a. Tutankhamen tomb: Some interesting chemical problems. Egyptian Gazette, March 22. Egyptian Gazette. 1923b. Tutankhamen tomb: Intensive work in the laboratories. Egyptian Gazette, March 27. Egyptian Gazette. 1923c. Tutankhamen tomb: Some interesting chemical problems. Egyptian Gazette, April 5. Egyptian Gazette. 1923d. The great conspiracy trial, amazing story of intrigue, revolvers, bombs and poison. Egyptian Gazette, April 21. Egyptian Gazette. 1923e. The great conspiracy trial, the attack on Mr. T. W. Brown, plan to use poisoned arrows. Egyptian Gazette, April 23. Englebach, R.1945. Alfred Lucas dies in Harness. Egyptian Gazette, December 9. Engelbach, R.1946. Introduction to Egyptian archaeology. Cairo: Imprimerie de l'Institut Francais d'Archeologie Orientale. Fakhry, A.1947a. A note on the tomb of Khreuef at Thebes. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte42:44–451. Fakhry, A.1947b. A report on the inspectorate of upper Egypt. Annales du Service des Antiquit�s de L'�gypte46: 25–61. Fink, C.G., and A. H.Kopp. 1933. Ancient Egyptian antimony plating on copper objects. Metropolitan Museum Studies4:163–67. Gilberg, M.1987. Friedrich Rathgen: The father of modern archaeological conservation. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation26:105–20. Gummel, H. 1938. Forschungsgeschichte in Deutschland. Berlin: W. de Gruyter. Hammond, P. W.1993. Personal communication. Librarian, Laboratory of the Government Chemist, Teddington, Middlesex, U.K. Hammond, P., and H.Egan. 1992. Weighed in the balance. London: HMSO. Hoving, T.1978. Tutankhamun, the untold story. New York: Simon and Schuster. Hurst, H. E.1945–46. Alfred Lucas. O.B.E., F.R.I.C., F.S.A. Bulletin de l'Institute d'Egypte28:163–64. James, T.G.H.1992. Howard Carter: The path to Tutankhamen. London: Keegan Paul International. Johnson, J.1993. Conservation and archaeology in Great Britain and the United States: A comparison. Journal of the American Institute of Conservation32:249–69. Lee, C.1992. “… the grand piano came by camel”: Arthur C. Mace, the neglected archaeologist. London: Mainstream Publishing. Lucas, A.1902. The disintegration of building stones in Egypt. Cairo: Geological Survey Department, Public Works Ministry.

Lucas, A.1920. Legal chemistry and scientific criminal investigation. New York: Longmans, Green and Co. Lucas, A.1921. Forensic chemistry. London: E. Arnold and Co. Lucas, A.1923a. Tutankhamen's tomb: Some interesting chemical problems. Times (London), April 5. Lucas, A.1923b. Letter to H. E. Winock. March 3, 1927. Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Lucas, A.1923c. Letter to Fairman, June 21, 1943. Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Lucas, A.1924. Antiquities: Their restoration and preservation. London: E. Arnold and Co. Lucas, A.1926. Ancient Egyptian materials. London: Longmans, Green and Co. Lucas, A.1938. The route of the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. London: Edward Arnold and Co. Lucas, A., and J. R.Harris. 1989. Ancient Egyptian materials and industries. Rev. ed.London: Histories and Mysteries of Man. McLean, M., and K.McDonnell. 1992. A survey of the Howard Carter and Alfred Lucas materials resulting from the discovery and excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun in the Griffith Archive of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, England, September 15–24, 1992. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. Mitchell, C. A.1920. Review of Legal chemistry and scientific criminal investigation, by Alfred Lucas. Analyst45:245–46. Mostyn, T.1989. Egypt's belle epoque, Cairo 1869–1952. London: Quartet Books. New York Times. 1923a. Pharaoh's chairs restored to beauty. New York Times, April 4. New York Times. 1923b. Saving tomb relics is chemical problem: Experts must determine character of changes in composition to preserve objects. New York Times, April 4. New York Times. 1923c. Spend day treating pharaoh treasures. New York Times, December 13. New York Times. 1923d. Pharaoh chariots plated with gold: Restoration reveals exquisite designs in precious stones, glass and faience. New York Times, December 24. New York Times. 1945. Dr. Lucas, survived “pharaoh curse.” New York Times, December 10. Otto, H.1979. Friedrich Wilhelm Rathgen. Berliner Beitr�ge zur Arch�eometrie4:42–112. Plenderleith, H. J.1934. The preservation of antiquities. London: Museums Association. Plenderleith, H. J.1935. Review of Ancient Egyptian materials, rev. ed., by AlfredLucas, Analyst60:64–65. Plenderleith, H. J.1946. Mr. Alfred Lucas, O.B.E. Nature157:98–99. Reisner, G. A.1928. Hetep-heres, mother of Cheops. Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts26:2–17. Reisner, G. A.1929. The household furniture of Queen Hetep-heres. Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts27:83–90. Reisner, G. A.1955. A history of the Giza necropolis. Vol. 2, The tomb of Hetep-heres, the mother of Cheops. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Robertson, R.1947. Alexander Scott, 1853–1947. In Obituary notices of the Fellows of the Royal Society of London. 251–62. Searight, S.1969. The British in the Middle East. London: East-West Publications. Seeley, N. J.1987. Archaeological conservation: The development of a discipline. Institute of Archaeology Golden Jubilee Bulletin24:161–75. Stoley, R. W.1927. Review of Ancient Egyptian materials, by Alfred Lucas. Analyst52:59–61. Thomsen, T.1940. Rosenberg, Gustaf Adolf Theodor (1872–40). Berlingske Tidende, December 4. Times (London). 1923a. The Egyptian treasure, work of removal, responsibility of the excavator. Times (London), January 31. Times (London). 1923b. Treasures of Luxor, Lord Carnavon's description, the experts task. Times (London), January 31.

Times (London). 1923c. Treasures from the tomb, experts work at Luxor, king's wonderful sandals. Times (London), February 1. Times (London). 1923d. Luxor's experts at work: Restoring the treasure. Times (London), February 26. Times (London). 1923e. Luxor work continuing: Preservation of treasures. Times (London), April 9. Times (London). 1923f. Tutankhamen's tomb: Restoration work in progress. Times (London), December 13. Times (London). 1923g. The pharaoh tomb: Preserving the specimens. Times (London), December 20. AUTHOR INFORMATIONMARK GILBERG received his B.S. and M.Sc. degrees from Stanford University, where he investigated the redox properties of transition metal centers. He was also a research assistant in the Department of Psychiatry, Stanford University Medical Center. He received his Ph.D. from the University of London Institute of Archaeology. In 1983 he joined the Conservation Processes Research Division of the Canadian Conservation Institute. In 1987 he was appointed scientific officer in the Materials Conservation Division of the Australian Museum. Since 1994 he has been research coordinator for the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training. Address: NCPTT, National Park Service, NSU Box 5682, Natchitoches, La. 71497.

Section Index Section Index |