WITH PAINT FROM CLAUS & FRITZ: A STUDY OF AN AMSTERDAM PAINTING MATERIALS FIRM (1841–1931)MICHEL LAAR, & AVIVA BURNSTOCK

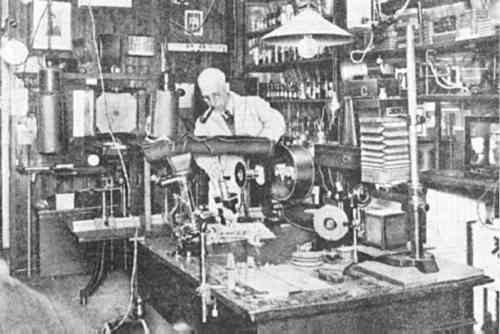

5 CONTROLThe letterheads of all Claus & Fritz's bills to Willem Witsen (Stichting Willem Witsenhuis) also mention “Restoration of Paintings,” an aspect about which nothing more is known since there are no extant archives of the firm. From 1917 onward there also appears the line: “Manufacturers of Oil and Water Colors. Under the control of Mr. van Ledden Hulsebosch.” This is a reference to the Amsterdam criminologist and scientific adviser to the Criminal Investigation Department, C. J. van Ledden Hulsebosch (1877–1952) (fig. 12), a celebrity in his day whom the newspapers dubbed “the Sherlock Holmes of Amsterdam.” Claus & Fritz evidently considered the quality of their products important enough to warrant taking on an independent controller, who presumably would have conducted regular tests to ensure the fineness, authenticity, and quality of the pigments. Van Ledden Hulsebosch carried out similar product control on the flavorings of Maggi in Amsterdam and the tubular lights made by Philips of Eindhoven.

Van Ledden Hulsebosch was also interested in modern methods of examining works of art. In his popular Veertig Jaren Speurdswerk (Forty Years of Detective Work) (1945) he described how, after World War I, he brought the first ultraviolet lamp to the Netherlands. After a great deal of difficulty he became the first in the country to examine oil paintings by Old Masters by UV radiation in order to discover signatures that were completely invisible in ordinary light. The difficulty was particularly severe when the painter had signed his name in one of the very luminescent types of paint such as zinc white or other paints containing zinc or in a nonluminescent paint on a luminescent ground (Van Ledden Hulsebosch 1945, 166). In addition to acknowledging his services, Van Ledden Hulsebosch's name on the firm's letterhead also had a commercial intention much like the signed document of 1900. |