ARTHUR B. DAVIES'S MOUNTAIN BELOVED OF SPRING: DETERMINING TREATMENT BY RECONSTRUCTING A PAINTING'S HISTORYNANCY R. POLLAK

2 DISCOVERY OF THE OVERPAINTED SKYAfter the varnish had been reduced over both zones of the painting, some material remained on the sky and background mountains (fig. 2). The surface of the sky at this stage was dirty, discolored, and uniformly flat. It was discordant with the brushwork and paint application in the rest of the painting, and it visually flattened the top third of the image. While the middle and foreground showed great color variety, a range of brushwork, and strong depth and perspective, the sky was lacking all of these. Microscopic examination of the edges of the painting, cracks in the paint surface, and the interface between mountains and sky strongly suggested that the entire sky and the background mountains had been overpainted after the rest of the composition was completed. The uppermost green-blue paint layer overlapped the top edge of the painting, extending very slightly onto the tacking edge but not completely covering a lower, bright blue paint layer. The uppermost paint also formed a hard edge that did not completely match the contours of the middle ground mountains and tree, again revealing a brighter blue paint beneath. In other areas, the green-blue paint overlapped and covered the edges of elements such as the foreground tree. The discolored surface did not respond to cleaning tests with aqueous systems and did not appear to be an embedded grime layer. Solvent tests with acetone and 2-propanol did not directly affect the uppermost layer but did appear to undercut the green-blue paint layer by dissolving a lower resin layer. These observations suggested that the discolored layer was overpaint, possibly applied at the time the structural treatment was undertaken.

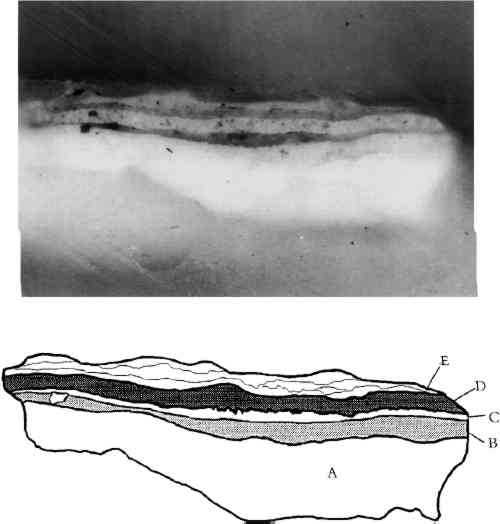

The preliminary physical evidence and the poor harmony between the sky and the rest of the composition suggested that the present condition of the sky was the result of a previous restoration rather than an artist's change. Unfortunately, no treatment history for the painting could be found. Further examination of the painting was then undertaken in an attempt to find additional evidence of previous treatment. The added gauzelike fabric seemed to be a strong indication that previous restoration had been undertaken. To further examine the structure of the additions and the condition of the original canvas, the painting was removed from the stretcher. The original canvas was in very good condition, with no staining or previous repairs visible. The added fabric proved to be a neatly applied strip lining, which extended very slightly beyond the fold of the painting. Visual examination of the fabric indicated that it was composed of cotton fiber, and the adhesive resembled a dry paste or animal glue. The stretcher face bore a slight ridge in the center of each member, suggesting that it may have been resurfaced. Thin wooden strips had been added to one edge of both stretcher panels with animal glue, presumably to prevent them from slipping out of their grooves when the stretcher was keyed out. While the neatness of the strip lining and the stretcher modifications suggested a 2.1 ANALYSIS OF THE PAINT STRUCTURE AND MATERIALSSince the painting as a whole could not offer more information, attention was turned to analysis of the pigments and layer structure of the paint in the sky. Pigment samples were taken from the upper, green-blue paint layer and the lower, bluer paint layer. The samples were taken from cleaned areas near the edge of the painting and mounted on double-sided carbon tape for elemental analysis or in Cargille Meltmount 1.662 for optical analysis. The medium was not removed from the samples prior to mounting. Optical properties of the pigments were observed by polarized light microscopy, and elemental analysis was performed using scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive x-ray analysis. The aim of the pigment analysis was to compare the pigments used in both paint layers and look for pigments in the upper paint layer that had been manufactured after Davies's death in 1928, indicating that the paint was not artist-applied (Martin 1995). Specifically, manganese blue and phthalocynanine blue and green would indicate an application date after Davies's death. None of these pigments were found in any of the samples. The lower blue layer appeared to be a rather simple mixture of white (lead, zinc, and barium pigments) and blue (smalt, possibly with cobalt and viridian), while the upper paint layer appeared to be composed of a wider variety of pigments, including zinc and barium pigments, cerulean blue, and possibly some black, yellow, red, and green pigments. Although experience suggests that paint used in retouching often contains a greater variety of pigments than the original paint mixture, the evidence produced was again Analysis of a cross section taken from the sky was more fruitful. A sample taken from a crack near the fold edge contained all layers from the ground to remnants of varnish remaining on top of the suspected overpaint layer (fig. 3). In handling, the sample broke into four fragments, which were mounted on a polyester capsule using Norland Optical adhesive #65. The mounted sample fragments were cut with a microtome to expose the complete layer structure and examined in visible and ultraviolet light at 50–500 x.

The cross section confirmed the observations made during cleaning tests and microscopic examination. The lower blue paint layer was applied directly over the ground in a smooth single layer, which was slightly thinner than the upper green-blue paint layer. Slight variations in thickness were probably due to the texture of ground and canvas. As observed in the analysis of the crushed pigment samples, this paint layer was composed primarily of white pigment intermixed with a small proportion of large blue pigment particles. In ultraviolet illumination, the paint layer appeared darker than the more autofluorescent ground and adjacent varnish layers. No significant grime accumulation was present on top of the blue paint layer, and the varnish appeared to sit directly on top of the paint with no great degree of intermixing. The varnish layer directly above the lower blue paint layer appeared very dark brown in visible light and autofluoresced a uniform, bright white in ultraviolet light, indicating it was a single, homogeneous layer. While particulate matter was visible on the upper surface of this layer and intermixed slightly into its surface, there was no evidence that pigments were deliberately mixed into the resin layer to produce a glaze or scumble. Rather, the large, irregular character of the particulate and its uneven distribution (more was located in recessed areas) strongly suggested a grime layer, indicating that the lower blue paint and varnish were exposed for some time before the application of the green-blue paint layer. The upper surface of the interlayer varnish was turbulent, and the interface between the varnish and upper green-blue paint layer appeared indistinct. The varnish surface may have been disrupted by partial cleaning, and the two layers may have intermixed after application of the green-blue paint layer. This particular sample also showed that the resin layer between the two paint layers was not even and appeared pooled in lower areas of the paint. This uneveness may also indicate that the varnish had been reduced (or an unsuccessful attempt had been made to remove it) prior to the application of the second paint layer. The upper green-blue paint layer presented characteristics very different from those of the lower blue paint layer. In visible light the upper layer was decidedly more yellow, and in ultraviolet light the layer was less autofluorescent than the lower blue layer. The upper paint layer also appeared to be composed of a greater variety of pigments, and large red, blue, white, and yellow particles were mixed with the smaller, yellowish particles that predominated the matrix. Varnish layers on top of the second paint layer included two natural resin layers with interlayer grime and remnants of a topmost synthetic varnish. The extended examination of the painting and analysis of samples led to the following conclusions: The painting had been removed from its present stretcher in the past; structural work in the form of a strip lining and stretcher modification had occurred; and a second paint layer was added to the sky over an existing varnish layer. No added paint layers were apparent in the other areas of the painting. There was no evidence, such as modern pigments, to date these changes after Davies's death in 1928. Therefore, while it appeared that the second paint layer in the sky was a restoration that occurred at the time of the structural modifications, there was still no proof that it was not done by the artist himself. 2.2 COMPARISON OF TECHNIQUETo gain a better understanding of Davies's technique and to place Mountain within the context of his work, other paintings by Davies were examined. In addition to many of Davies's watercolors and graphic works, the Addison owns several paintings on canvas. The earliest dated painting in the collection was completed by 1905, shortly before Mountain Beloved of Spring was painted. Three landscapes from 1927 served as excellent examples of Davies's work at the end of his career. The three paintings from 1927, depicting very different landscape images, show many similarities in technique, including a paint surface in which the canvas texture remains visible, a strong sense of compositional depth, rich coloring, and sure execution, with little obvious evidence of reworking. Apuan Mountains, Lucca (26 � 39 in.) is a somewhat subdued landscape of cattle among green hills with a gray, overcast sky. The paint application is very thin, with the ground or a lower white paint layer visible below brush strokes and thinner color washes. The landscape is primarily composed of multiple thin layers of color in a rich variety of blues, greens, and earth tones. Davies appears to have used a medium-rich paint, and brush strokes retain a distinctly fluid character, especially apparent in thicker accent strokes in the mountains and foreground. The sky appears to have been painted in a single layer of very pale bluish white paint, with a few crisp-edged strokes of blue depicting a break in the cloud cover. In the sky, there is no evidence of reworking, and the sky meets the mountains with clean edges. The painting recently underwent conservation treatment, and no evidence of extensive overpaint or major areas of reworking was recorded. The paint surface presently has a clear, uniform varnish layer. Umbrian Hills, Near Urbino (18 � 30 in.) is painted in a manner similar to that of Apuan Mountains, but the landscape is brighter, consisting primarily of rolling hills dotted with buildings and livestock, backed with a narrow band of sky. A strong canvas texture is very visible throughout the image. Livestock and buildings are painted primarily with thin color layers, accented by much thicker strokes that at times exhibit a low relief. The blue of the sky is painted in one layer, with the ground or a lower white paint layer used to give definition to the sky at the horizon. The paint surface presently bears a slight layer of grime and discolored varnish, and the painting appears to have undergone some conservation treatment, although no treatment records were found. In the third painting from 1927, Matese Mountains (26 � 39 in.), the sky is the primary focus of the composition, constituting the majority of the image and stunning for its strong, vibrant blue color. The paint application is very fluid, and Davies's brush strokes remain visible, particularly as he moved the paint around the contours of the mountains. In this painting, it is very clear that the sky is painted in a single layer with no reworking. The remainder of the landscape is painted with techniques similar to the other two paintings. The paint surface is very fresh with a clear varnish coating and appears to have undergone recent conservation treatment. The 1905 painting, Hills and Valleys (18 � 30 in.), was examined as an example of Davies's technique around the time Mountain was painted. In Hills and Valleys, the landscape is dominated by a figure in the foreground and cattle in the middle ground. While the imagery differs from the other pure landscapes, Davies's technique of using multiple thin paint layers with heavier accent strokes is apparent. However, in this instance, the layering also seems to include areas that have been reworked, and throughout the image, darkened pools of a resinous material can be seen between paint layers. This is particularly evident in the sky, where the edges of clouds are indistinct, and paint and lower varnish layers overlap compositional elements in a haphazard manner. These indistinct edges appeared very similar to the overlapped edges of the trees and mountains in Mountain Beloved of Spring. The 1927 landscapes and the two earlier paintings showed similar techniques, particularly in the use of a mixture of multiple thin paint layers and thicker accent strokes. However, whether the sure execution and strong coloring seen in the 1927 paintings were also present in Davies's earlier work remained unknown. In the mountains and landscape of Mountain Beloved of Spring, it did seem to be present, particularly in the single feathery brush strokes that defined the pine trees, the delicate color layers in the mountains, and the sense of depth defined by carefully placed, thicker brush strokes. An observation by an art critic of Davies's time may support the idea that the artist's landscape technique remained unchanged throughout his career: “It is difficult to say which is the more beguiling, the obviously accurate portrait of a place or the suggestion of a mood. Late in his career this fidelity to the phenomena of the things seen was almost as pronounced as in his earlier years” (Cortissoz 1931, 11). Looking at Davies's other work made it seem more unlikely that he had repainted the sky of Mountain. That portion of the composition was least harmonious with the rest of the image, and it bore no relationship to the skies of the later 1927 paintings. The lower blue paint layer, revealed during cleaning tests, did appear to be more like the coloration used in the 1927 skies and more in harmony with the rest of the image. However, while removal of the upper sky layer would probably produce a painting that was more harmonious, the idea that Davies had reworked the sky (with questionable results) remained a possibility that had to be carefully considered before treatment could proceed. The investigation returned to historical research in an effort to create a timeline for the life of the painting. 2.3 HISTORICAL RESEARCHAlthough a general chronology of Arthur Bowen Davies is available and his professional activities such as his involvement with the Eight and the Armory Show are well documented, little else is known about this private man. Davies led an incredibly complex double life that included his acknowledged wife and children living on a farm in Congers, New York, and his mistress and their child, with whom Davies lived in New York City under an assumed name. Apart from these lives, Davies maintained his studio and career as well. Few knew about this double life, and those who did closely guarded the secret, to the point of destroying all correspondence with Davies. It is unknown what insights about Davies's working methods and thoughts about his work may have been lost in protecting his private life. Although Davies further muddled his history by dating only a few of his paintings, this point does not greatly affect the history of Mountain Beloved of Spring. The subject can be tied directly to his 1905 trip to the American West, and the painting was probably executed between 1906 and 1907. Its first documented exhibition was at a show of landscapes by American artists held at New York's Union League Club, March 14–16, 1907. In 1910 it was exhibited at the American Arts Exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, Berlin, and the Royal Art Society, Munich. Exhibition labels on the stretcher confirm these venues and list the painting as owned by the art dealer William Macbeth. Davies had a close relationship with Macbeth beginning in 1888 and probably had consigned the painting to him shortly after its completion. The painting was subsequently It can be argued that this history abounds with opportunities for Davies to have altered Mountain himself, but each point has a strong counterpoint as well. Davies was a personal friend of both Macbeth and Bliss. Around 1895, he began living above the Macbeth galleries and remained close to the dealer for the rest of his life. If Macbeth had requested restoration of Mountain, it could be possible that Davies, being so close, undertook the project himself. However, Davies was financially secure, and it would seem unlikely that he would have accepted such projects for the income. Davies's prolific output during his career would not seem to allow time for restoration work. How Davies felt about restoration of his own work is unknown. He is known to have reworked some unfinished paintings from his early career at a much later date, but such reworkings generally involved figurative works, not pure landscapes. Davies exhibited Mountain shortly after it was painted, an indication that he felt it to be a finished work. Davies also enjoyed a close relationship with Bliss, the only known private owner of the painting. He advised her on her art collection and painted the murals for her music room. Their friendship raises the slight possibility that Davies modified Mountain to fit Bliss's environment or directed some modification to be done. This question is not easily resolved due to the loss of correspondence between Bliss and Davies. After Bliss gave the painting to the Addison Gallery in 1928, it was shown in several exhibitions, including a memorial exhibition in 1930 and traveling shows in 1960–61 and 1962–63. It is possible that the painting underwent treatment before Bliss donated it or prior to any of these shows. An exhibition condition report from 1962 noted that the surface coating was “irregular in coverage and gloss, discolored, and grimy” (Clapp 1962). This was also the state of the painting in 1994, suggesting that the second paint layer had been applied some time before 1962. 2.4 PHOTOGRAPHIC DOCUMENTATIONThe most direct historical evidence of the previous state of the painting was a Peter Juley photograph now in the Addison Gallery files (fig. 4). Juley photographed the Addison's collection around 1930, and although it is undated, this photograph may be of that set. Macbeth may have also had Juley photograph Mountain while it was in his possession, which means the photograph was taken no earlier than 1906 (or when Davies completed the painting) and no later than 1930 (when the Addison Gallery's collection was photographed). Four other Juley photographs of Davies's paintings in the Addison's files are printed with a process different from that used for Mountain. These other photographs are decidedly yellow in tone, and the images appear to have undergone some fading. The four paintings were all in the Addison's collection at the time Juley photographed it, and their photographs probably represent his work done for the Addison. Because the photograph of Mountain is so different, it was most likely taken at a different time, possibly earlier, when it was in Macbeth's possession.

The photograph of Mountain appears to be a silver gelatin process made to mimic a platinum print. The paper support is in excellent condition, and the silver image has not faded or discolored. The corners of the photograph, particularly at the bottom, are slightly lighter, but this problem is probably in the original negative rather than the result of later fading of the print (Norris 1995). Compared to the painting, the photograph registers blues, greens, and reds throughout the image, indicating that a panchromatic film was used and the painting was accurately recorded (Evans 1995). The photographic image emphasizes the canvas texture of the painting, probably due to the lighting conditions used during photography. The most notable aspect of the Juley photograph of Mountain is the range of values seen in the sky. In the photograph, a distinct tonal shift can be seen from left to right in the sky, with the right side of the sky being much lighter. The dark tone of the foreground tree indicates that the lightness in this area is not the result of fading but rather records value differences in the painting. Other distinct differences between the photograph and the painting in its partially cleaned state were observed. In the middle and foregrounds, the photograph shows great depth and tonal variety to the image and the strong texture of the canvas beneath the paint layer. Even if this texture were heightened in the painting by mimicking the lighting seen in the Juley photograph, the varnish remaining on the painting was thick enough to obscure it. Tonal and spatial relationships in these areas were also slightly distorted by the varnish. Cleaning tests to remove the remaining varnish in the middle and foregrounds indicated that the lower paint layers were intact and the varnish could be removed evenly to the paint surface. The varnish that was removed continued to be a dark, translucent amber in color, as noted in the initial varnish reduction; no sensitive glazes were noted, with the exception of a very few small dark blue accents in a middle-ground tree. The Juley photograph not only shows a tonal shift across the sky but also indicates the presence of brush strokes and small lighter areas that give the sky definition. In addition, the background mountains appear lighter in relationship to the middle mountains. These differences could not be observed in the painting during treatment because the green-blue upper paint layer was uniformly applied across the sky and distant mountains, producing a flat, even appearance. While it was felt that the Juley photograph represented an earlier state of the painting before the second paint layer was added, the date of the second paint layer still could not be determined. The other early reproduction of the painting that was found was in the catalog of the 1930 Memorial Exhibition of the Works of Arthur B. Davies held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Metropolitan Museum of Art 1930). In the catalog reproduction, the sky appears flat and opaque, similar to the present appearance of the overpainted sky. While at first it would appear that the Metropolitan reproduction and the Juley photograph show two different states of the painting, the many variables of the photographic and printing processes could mean that the Metropolitan reproduction was taken from the Juley photograph and the subtleties of contrast were lost in printing. There was no documentation of the photograph given to the Metropolitan for use in the catalog, and the Juley photograph is the only existing one from that time period that has been found. Once again, circumstantial evidence produced no firm conclusions. |