THE DILEMMA OF INTERPRETING AND CONSERVING THE PAST AT NEW YORK STATE'S HISTORIC SITESDEBORAH LEE TRUPIN, DAVID BAYNE, MARIE CULVER, NANCY DEMYTTENAERE, HEIDI MIKSCH, & JOYCE ZUCKER

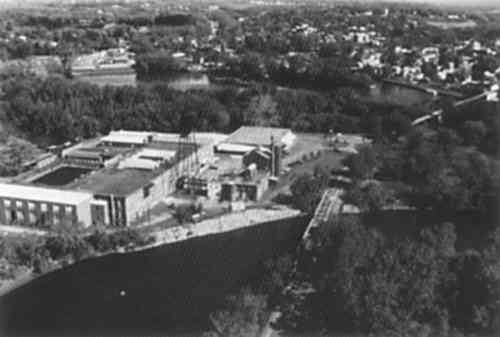

1 INTRODUCTIONNew York State's historic site system originated in 1850 when the state acquired Washington's Headquarters in Newburgh, the nation's first publicly owned historic site. During the next 120 years, the site system developed from a decentralized collection of properties into the Bureau of Historic Sites, an integral part of the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation. The system today comprises 34 historic sites as diverse as Revolutionary War battlefields, large estates, Erie Canal structures, the archaeological remains of a 17th-century Iroquois town, and Frank Lloyd Wright's Darwin Martin House. Headquarters for New York State's Bureau of Hisoric Sites (fig. 1) is a rehabilitated early 20th-century textile bleaching complex located on Peebles Island State Park, at the confluence of the Mohawk and Hudson Rivers, 15 miles north of Albany. Peebles Island staff provide technical support for the historic sites, including exhibit design and fabrication, restoration (which in the bureau encompasses exterior and interior architectural and landscape preservation issues), interpretation and research, archaeology, curatorial services, collections management, conservation, and protective services.

The conservation laboratories at Peebles Island treat archaeological materials, objects, furniture, paintings, paper, and textiles. The 2,000-square-foot labs were planned for four staff members apiece, but this ideal figure has never been realized. There are currently six conservators, one full-time and one part-time technician, and two assistant contract conservators. To facilitate communication with other staff, one conservator serves each year as conservation chair. Interns and volunteers have regularly supplemented the conservation staff. Skilled needleworkers and weavers contribute approximately 600 hours per year to the textile lab. Students from local universities have worked an average of 1,000 hours each year in the archaeology conservation lab. Beginning with the paintings lab in 1975, the bureau conservation labs have sponsored internships for aspiring conservators; these internships have helped 35 students become professional conservators. Once trained, these students and volunteers provide dedicated and skilled assistance. The site system includes 245 historic structures, 350,000 historic and artistic objects and manuscripts, and approximately 800,000 archaeological artificats. Site resources also include nearly 200 outdoor sculptures and The large number of properties and their distribution throughout the state contribute to a complex set of collection conservation issues. In addition, the historic structure often serves as storage space, display area, and stage set for a particular time period, without the separate and controlled areas that can be designated for these uses in many museums. Collection artifacts in historic settings have traditionally been placed in minimally controlled environments in lightly staffed houses, their placement inspired by historic record rather than by standard principles of collection care. As inheritors of a system immersed in this tradition, conservators have been expected to be advocates for collections issues and respond to the system's particular needs with suitable, practical, and ethical solutions. The evolution of the bureau's conservation program reflects ongoing efforts to resolve these differences. The role of conservator at Peebles Island has never been viewed strictly as that of benchworker or craftsperson. Unlike the hierarchy at some older institutions, the staff structure puts conservators and curators on an equal basis. The development of the bureau's conservation program thus reflects the maturation of not only the state's historic site system but of the conservation profession itself. |