THE DILEMMA OF INTERPRETING AND CONSERVING THE PAST AT NEW YORK STATE'S HISTORIC SITESDEBORAH LEE TRUPIN, DAVID BAYNE, MARIE CULVER, NANCY DEMYTTENAERE, HEIDI MIKSCH, & JOYCE ZUCKER

ABSTRACT—This paper discusses the development of New York State's 34-unit state historic site system and its museum support and conservation center (Peebles Island) located in Waterford, New York. Then diversity of the state historic sites and their collections presents a wide range of conservation problems. Recognizing this, New York State Bureau of Historic Sites conservators and other staff have used teamwork and consensus building to develop suitable, practical, and ethical conservation responses for these collections. Problems, solutions, and new directions in collections assessment, environmental management, collections storage, and interpretation are discussed in detail. 1 INTRODUCTIONNew York State's historic site system originated in 1850 when the state acquired Washington's Headquarters in Newburgh, the nation's first publicly owned historic site. During the next 120 years, the site system developed from a decentralized collection of properties into the Bureau of Historic Sites, an integral part of the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation. The system today comprises 34 historic sites as diverse as Revolutionary War battlefields, large estates, Erie Canal structures, the archaeological remains of a 17th-century Iroquois town, and Frank Lloyd Wright's Darwin Martin House. Headquarters for New York State's Bureau of Hisoric Sites (fig. 1) is a rehabilitated early 20th-century textile bleaching complex located on Peebles Island State Park, at the confluence of the Mohawk and Hudson Rivers, 15 miles north of Albany. Peebles Island staff provide technical support for the historic sites, including exhibit design and fabrication, restoration (which in the bureau encompasses exterior and interior architectural and landscape preservation issues), interpretation and research, archaeology, curatorial services, collections management, conservation, and protective services.

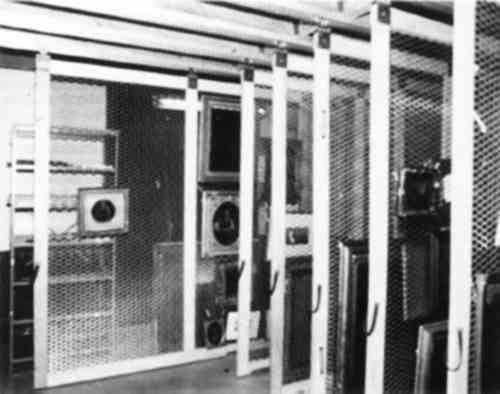

The conservation laboratories at Peebles Island treat archaeological materials, objects, furniture, paintings, paper, and textiles. The 2,000-square-foot labs were planned for four staff members apiece, but this ideal figure has never been realized. There are currently six conservators, one full-time and one part-time technician, and two assistant contract conservators. To facilitate communication with other staff, one conservator serves each year as conservation chair. Interns and volunteers have regularly supplemented the conservation staff. Skilled needleworkers and weavers contribute approximately 600 hours per year to the textile lab. Students from local universities have worked an average of 1,000 hours each year in the archaeology conservation lab. Beginning with the paintings lab in 1975, the bureau conservation labs have sponsored internships for aspiring conservators; these internships have helped 35 students become professional conservators. Once trained, these students and volunteers provide dedicated and skilled assistance. The site system includes 245 historic structures, 350,000 historic and artistic objects and manuscripts, and approximately 800,000 archaeological artificats. Site resources also include nearly 200 outdoor sculptures and The large number of properties and their distribution throughout the state contribute to a complex set of collection conservation issues. In addition, the historic structure often serves as storage space, display area, and stage set for a particular time period, without the separate and controlled areas that can be designated for these uses in many museums. Collection artifacts in historic settings have traditionally been placed in minimally controlled environments in lightly staffed houses, their placement inspired by historic record rather than by standard principles of collection care. As inheritors of a system immersed in this tradition, conservators have been expected to be advocates for collections issues and respond to the system's particular needs with suitable, practical, and ethical solutions. The evolution of the bureau's conservation program reflects ongoing efforts to resolve these differences. The role of conservator at Peebles Island has never been viewed strictly as that of benchworker or craftsperson. Unlike the hierarchy at some older institutions, the staff structure puts conservators and curators on an equal basis. The development of the bureau's conservation program thus reflects the maturation of not only the state's historic site system but of the conservation profession itself. 2 ASSESSMENT AND PLANNINGIn the mid-1970s, conditions in many museums and historic houses were less than optimal by current standards. This was true of New York's Staff from all bureau units surveyed Bicentennial sites such as Washington's Headquarters. While buildings were investigated for the integrity of the exterior envelope (the outer shell of walls, roof, and foundation) and interpretation was updated with an energetic new exhibit program, collections assessments began. Despite poor storage, erratic climatic conditions, and care that ranged from benign neglect to overzealous maintenance, the overall condition of the collections was fair. Following site visits, conservators prepared summary reports on the sites and then surveyed and treated objects proposed for Bicentennial exhibits. General collections surveys continue to be extended and updated; however, objects needed for exhibits or loans continue to determine treatment priorities. They are still treated before others that may have a greater inherent need for stabilization treatment, except in emergencies. The perpetual problem of balancing available staff time with the sites' needs was especially evident when—following a 1975 fire at Crailo in Rensselaer—laboratory work for other sites stopped. Staff members devoted all their time to preserving water-damaged collections until conditions were stabilized. Fortunately, this quick and comprehensive response saved objects damaged in the fire. The event served to promote the development of disaster preparedness plans at sits throughout the state, but the time lost to treat previously scheduled objects could never be replaced. Recently the bureau has chosen to focus on the development of historically accurate furnishing plans, which represent another priority for limited staff time. These plans describe the interior decoration as well as the location of historic artifacts within a room, using available records along with a knowledge of period practices. This approach involves the coordination of specialists in various disciplines. Team-based restoration of an entire room is a departure from the traditional approach of prioritizing individual conservation treatments. The conservator looks not only at the condition of an artifact but also at its appearance in relation to other components of a furnished room. Staff at Mills Mansion in Staatsburg, for example, researched the original room settings of the 1895 mansion and concluded that the original interior design elements had been carefully integrated to create an overall impression. The re-creation of this indefinable character was therefore a critical goal of restoration. The prominence of textiles in the decorative scheme, as upholstery, carpets, and draperies, meant that these materials assumed primary importance in the renovation. A textile conservation survey showed that the mansion retained almost all of its original furnishings and furnishing fabrics and so represented a unique resource upon which to draw. An initial planning team designed a highly structured brainstorming session, which was attended by an expanded team of five outside consultants and 10 bureau and site staff members. The purpose of the multidisciplinary meeting was to elicit opinions on two major issues: (1) the extent of replacement necessary to preserve original fabric while not jeopardizing the authenticity of the mansion and (2) how to retain the impression of the mansion given the necessity of incorporating some new fabrics. Similar questions occur in large-scale restoration projects at other sites and have proven difficult to answer clearly. The team members at Mills Mansion agreed to recommend the installation of reproductions of historic window treatments to control light and heat and recognized the necessity of retiring all historic draperies from display. They also In the Mills Mansion pilot project, insights from object-specific surveys supported treatment decisions within the context of a broadly based research effort. To further encourage a comprehensive approach to collections care, in 1992 the bureau adopted the National Institute for Conservation/Institute for Museum Services Collections Assessment Program (CAP) as a model for in-house assessments. For the first time, a bureau collections conservator and a bureau restoration coordinator worked jointly to produce a unified assessment of the buildings and collections needs of a site. Findings and recommendations of these ongoing studies now form the basis for long-range preservation strategies for each historic site. Consistent patterns in conservation concerns have become apparent. These concerns include environmental management, storage needs, and inherent risks facing collections on display. 3 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENTThe variety of climate control systems among the sites is problematic. Some sites still have the mechanical heating systems that were in place when the state acquired them; others have complete heating, ventilating, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems that have created new problems. The comprehensive HVAC systems introduced in the 1970s were intended to achieve the environmental standards of that era. These large mechanical systems were installed outside of the historic house, with underground pipes to carry glycol-water mixtures inside to air handlers and exchange units. One drawback of these systems, aside from the subsoil disturbance of archaeological evidence required for their installation, is the costly outside expertise required for repair or adjustments. Despite contractual arrangements, these experts are not available when crisis strikes. More important, there is increasing evidence that these systems cannot effectively maintain adequate relative humidity (RH) levels for collections without damaging the historic structure itself. Furthermore, experience from the past 10 years indicates that such systems do not even maintain good conditions for collections; indeed, at times they provide conditions that can be destructive. Monitoring at sites with 1970s systems has shown that RH levels are excesively high in summer and low in winter, just as they are in sites without modern systems. Efforts in environmental management now include the creation of controlled local environments. When the entire heating system failed at Senate House, Kingston, in December 1992, furniture was grouped in the center of the rooms and covered with blankets to slow environmental shifts. This technique proved fairly successful. During this two-week period, outside temperatures fluctuated widely. Internal changes were effectively moderated by the masonry walls and the blankets. Although the coverings were light (averaging one blanket thick), they slowed the environmental response time by several hours and prevented rapid, injurious variations in RH. Unfortunately, the lessons learned from such experiences are only slowly realized, but each episode produces Attempts to monitor interior environments throughout the system have been inconsistent. Hygrothermographs frequently are neglected because staff members are busy. Even when the instruments have been maintained, years of data often have been collected without being analyzed. Beginning in 1994 the bureau will phase in the use of electronic loggers, and the responsibility for their maintenance will shift to the conservators. The loggers are set to record the temperature and relative humidity every 30 minutes for 6 months. The accumulated data can then be extracted in the format desired—daily, weekly, monthly, etc. Hygrothermographs will continue to be used on site so daily conditions can be observed. Another significant environmental concern for historic houses is lighting. Some houses are fitted with ultraviolet-filtering films, storm windows, and interior shutters; others have no light barriers at all. In many cases period documentation dictates where objects should be placed; these decisions frequently clash with good conservation practice. The only solution may be to minimize the intrusion of light with UV filters, drapes, rotational displays, or covers. While only sparse records of monitoring and adjusting light levels exist, it is clear that past attempts to control light levels failed to reconcile conservation standards with the needs of period interpretations. Monitoring shows that some forms of ultraviolet filters applied even 10 years ago are still effective. Unfortunately, there is a temptation among site staff to believe that UV filters eliminate all potential for damage by light. Education of site staff and monitoring of light levels by consevators will be necessary to maintain awareness of the threat posed by all types of light. Environmental management remains one of the most important yet perplexing issues conservators contend with in historic houses. One approach under consideration is to hire a roving conservator who would, among other duties, be responsible for environmental monitoring. 4 STORAGEMany sites suffer from severe overcrowding in storage areas. As furnishing plans increasingly convert rooms for public display, storage spaces are relocated to the least desirable rooms or to various outbuildings. Some sites continue to acquire collections even after storage spaces have reached capacity. A few sites have resorted to using the storage wing at Peebles Island, but most seek on-site solutions. New construction has obvious advantages. In 1980 a metal pole barn was built at Lorenzo, in Cazenovia, to house a collection of 35 carriages, wagons, and sleighs. This space was secure and weather-tight. Twelve years later it proved to be flexible as well when the building was subdivided to make space for furniture sorage. The newer storage area was provided with good insulation, heat and humidity controls, and ventilation. Conditions are monitored with a hygrothermograph and have been satisfactory to date. The layout, size, and historic significance of site landscapes often prohibit new construction. Outbuildings are used if they are secure, but often the only alternative remaining space is within the historic house, where structural considerations are paramount. Placement of shelving in a designated room is the simplest solution and usually requires only careful calculation of the load-bearing capacity of the supporting beams. Heavy collections, however, such as textile or painting storage racks, require more sophisticated installation and can represent an unacceptable load on a historic structure. Restoration specialists and conservators developed two systems that transferred weight from floors to ceilings. The design for paintings storage racks at Olana, near Hudson, included

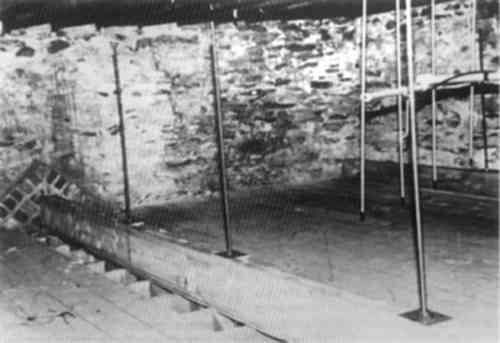

The second ceiling-suspension installation was designed for large rolled textiles at Mills Mansion. Four floor-to-ceiling columns were installed, each held in place by pressure, with only a single bolt in the ceiling needed to stabilize each column. The columns were used to support a new loft level. The original bed and canopy from this room now rest on top of the new loft. The loft provides support for chains that hold pipes for the rolled textiles. Besides the columns, little else is built into this room. The walls were cleaned, documented, and painted white in preparation for storage. Restoration coordinators voiced concern about covering the original wall color. Collections conservators agreed that repainting was not necessary, and for subsequent storage conversions walls have simply been cleaned. While conservators have developed some useful guidelines for storage areas, the diversity of the historic sites necessitates a case-by-case study for each site's storage requirements. 5 INTERPRETATIONThe majority of the bureau's exhibited collections are displayed in period room settings. Unfortunately, this method of interpretation can place collections at great risk. Security concerns are met in various ways: by placement of vulnerable collections out of reach, regardless of their historical location; by limited use of monofilament line and museum wax to secure small objects discreetly; and by watchful interpretive staff guiding relatively small tours. These efforts supplement more sophisticated electronic security systems. In addition to security concerns, interpretation of period rooms results in other losses. Historic carpeting—though protected by tour runners—is still walked upon. Historic drapery hangs in windows, exposed to varying light levels, dust, and gravity. No matter how much care is taken, a degree of deterioration occurs through the use of artificats as furnishings. Those who work with historic presentations accept the premise that the problems inherent in open display should be weighted against the bureau's commitment to present history accurately and to assure that the artifacts owned by the State of New York remain accessible to visitors. Many difficult display problems have been solved using nonintrusive structural reinforcement to mitigate stress and permit historically accurate presentations. Johnson Hall at Johnstown is an example. Sir William Johnson (1715–74), the British superintendent of Indian affairs for the Six Nations, was host to hundreds of Native Americans and included their cultural material in his home. Documents among his

Other objects also lend themselves well to the addition of discreet structural support. Due to distortion of the wooden frame of a pianoforte at Clermont, near Germantown, its legs can no longer support the body of the piece. Furniture conservators fabricated a metal support and painted it to blend with the wall, woodwork, and flooring. The support now safely and convincintly supports the pianoforte. At Olana, conservators have made individual mounts for all the objects displayed on a map case in Frederic E. Church's studio to allow his arrangement of intentional clutter to be presented safely. Recently, the bureau has introduced another facet of interpretive experience in some period rooms. Staged scenarios of well-researched aspects of daily life are used to provide insight into the life-styles of the people who occupied these homes. While collections are displayed in ways that more readily show how they would have been used, this approach can place additional stress on objects and put them at greater risk of damage. The success of scenarios has been followed by the desire to enhance the “reality” of the vignette through the use of foodstuffs, plants, flowers, and even aromatic aerosol sprays and fake dust. These suggestions were countered with a conservation request to use artificial and stable material whenever possible and plea to avoid the fake dust and aromas altogether. A team of conservators, curators, and site staff produced guidelines for the use of plants and flowers to minimize the risks of spills, breaks, stains, and insect damage associated with these materials. In response, many sites have invested in high-quality artificial plants, flowers, and foods. The use of reproductions has become increasingly necessary in the re-creation of historically accurate interiors. Reproduction items are used when original material is no longer extant, has deteriorated to a point where it can no longer be used as intended, or would be put at risk by further use. The bureau has an active program for reproduction purchasing and fabrication. All reproduction items are labeled as such as dated. Some conservators would like to see the use of reproductions expanded to include substitution for existing fragile historic resources, such as draperies and carpets. While this idea would solve some problems, it fails to address curatorial concerns about authenticity of In instances where visitor interaction is desirable, rooms are entirely furnished with reproduction material. The Children's Room at Johnson Hall, for example, is entertaining for children of all ages, and visitor reaction shows that this method is successful for interpreting past life-styles. Interpretation by guides is vital, both for initiating the use of material in this room and for emphasizing the difference between these reproductions and the historic objects displayed elsewhere in the house. These explanations provide an excellent opportunity to educate visitors about the need to conserve and care for original material so that it will be available for the enjoyment of future generations. Special events are major interpretive efforts at all of the historic sites. They enable sites to increase and broaden visitation, to interpret different aspects of site history and, through Friends' groups (private nonprofit groups that support many sites), to broaden membership and raise money. Fund raising and entrepreneurial endeavors are becoming increasingly important parts of a successful site program. Without question, however, special events can put the collections and historic buildings at risk. All events must comply with New York State building and fire protection codes, which limit occupancy and the use of open flames. In addition, they must also comply with the bureau's Special Events Guidelines, developed with conservators' input. These guidelines are intended to mitigate risks by, for example, suggesting cautious and limited use of traditional decorating materials on or near collections items. 6 CONCLUSIONSAn aging historic site system presents endless tasks demanding new and innovative solutions. Not all new solutions prove workable or desirable. Nonetheless, museum professionals must proceed with their responsibilities while keeping a cautious eye on the quick-fix and the ultimate solution. At the New York State Bureau of Historic Sites, project teams have proved to be useful in recognizing and solving problems ranging from the presentation of a portrait to comprehensive room restoration. When representatives of the sites, regions, and Peebles Island meet to plan a project's advancement, items needing resolution are discussed in an open forum. While not everyone may concur in all aspects of the final decision, everyone is heard. This approach is a great stride forward from the custodial-style management of the historic sites in previous years, when decisions were handed down from a central authority with little, if any, additional contribution. But more than just museum administration has changed in the past 20 years. Equally important, visitors to historic sites have become more sophisticated and knowledgeable. They have also become more demanding. New York State's historic site system competes with other cultural, recreational, and entertainment activities for visitors' interest and support. Historic sites are under continual pressure to increase visitation by offering unique types of experiences. At the same time, New York State Parks' mission statement calls for responsible stewardship of the state's natural, historical, and cultural resources. The conservators at New York State's Bureau of Historic Sites will continue to be tested in their dual roles as facilitators and preservers of the vulnerable and nonrenewable collections committed to their care. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe authors are grateful to New York State's Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation for supporting our writing of this paper and to Kristin L. Gibbons of the Bureau of Historic Sites for her assistance in editing. AUTHOR INFORMATIONDEBORAH LEE TRUPIN, DAVID BAYNE, MARIE CULVER, NANCY DEMYTTENAERE, HEIDI MIKSCH, and JOYCE ZUCKER are conservators for the New York State Bureau of Historic Sites. They hold conservation degrees from the New York University Institute of Fine Arts, the Smithsonian Institution's Furniture Conservation Training Program, the Cooperstown Graduate Program, George Washington University, and University of Delaware/Winterthur's Art Conservation Program. They have worked at Peebles Island for an accumulated total of 52 years. Address: New York State Bureau of Historic Sites, Peebles Island, P.O. Box 219, Waterford, N.Y. 12188.

Section Index Section Index |