HISTORIC UPHOLSTERY: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON TREATMENTELIZABETH LAHIKAINEN

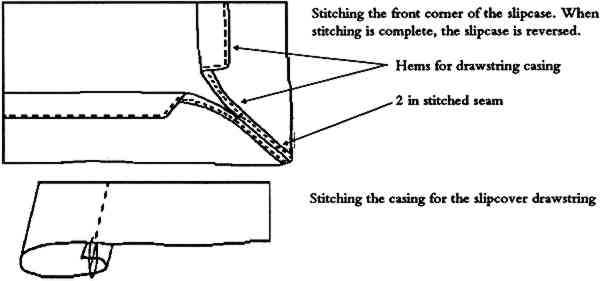

ABSTRACT—Developing a conservation plan for upholstered objects involves evaluation of historical evidence on the object, assessing other historical resources such as period documents and similar objects with extant upholstery or upholstery evidence, and designing a treatment that will preserve all original materials. Because traditional upholstery techniques introduce thousands of new holes with each reupholstery, the last decade has seen great advancement in the technical development of methods that serve both areas of concern—historical accuracy and preservation of materials. 1 INTRODUCTIONHistoric upholstery and its conservation are a new field of study in the decorative arts. Within the past decade scholars and conservators have made significant new discoveries about the social, economic, technological, and aesthetic history of the upholstered artifact. This new information has demanded a new approach to the analysis and conservation treatment of these three-dimensional and complex objects. As scholarly research uncovered new facts about upholstery practices of previous generations, curators placed new demands on conservators to achieve historical accuracy when preparing objects for exhibition. As conservators were called upon to treat upholstered objects, it became increasingly clear that developing new technology for reupholstering these artifacts was imperative to preserve the artifact and protect historical evidence. As a Textile Update Session paper, this article presents information that is not specific to new research by the author but rather a review of general trends in the field as a whole. The generally accepted process of how treatment is approached is outlined by the subject headings. Upholstery conservation solutions, research, and innovative work, some of it published (see Further Reading), have been produced by a number of institutions and individuals. It should be noted that advances and contributions by one individual or institution have been used as building blocks for work by others, so it is difficult to credit a specific advancement. Technical solutions to a particular problem reflect the biases and skills of individual specialists. Since many of the specifics of treatment change considerably from lab to lab, individual solutions are too numerous to describe thoroughly in one paper. The purpose of this article is to provide basic information to those unfamiliar with historic upholstery and its conservation, an outline of an accepted approach to this type of object, and brief descriptions of possible solutions. 2 HISTORICAL EVIDENCEMuch of the physical evidence retained by the upholstered object is fragmentary. A yarn or even just a fiber of the original finish fabric embedded under an old tack can confirm the fiber content and indicate a color and possibly the quality of the original cover. Due to the fragile nature of this type Decades and, in some cases, centuries of disposing of secondary materials during repair and reupholstery have resulted in a great deal of loss of original material and historical evidence. Seating furniture especially suffers from extensive repair and replacements due to the time-honored practices of restoration and reupholstery. Out of necessity the conservation community has responded by developing new methods of analysis and treatment that are both passive in regard to original materials and respectful of historical knowledge and materials. 3 ANALYSISIntensive examination of the materials is required to understand and discover an object's history. This evidence can then be used to reconstruct the original aesthetic intent of the piece if it is appropriate to do so. Analysis is an especially important step for seat furniture that no longer retains upholstery materials. It is possible, however, to uncover many facts regarding a piece through thorough examination. Vegetable matter and therefore region of production can be identified if any flower is left in the stuffing; fade marks in an original finish on the back post of a chair can reveal original height of the upholstery; the number and size and shape of holes in the wood frame can help determine upholstery technique that influenced the original form; and so on. An upholstered object can be difficult to evaluate because it can incorporate so many different components and several generations and qualities of repair and restoration. Condition is always a variable component of examination. Current conservation practices dictate that preservation of historical material, including evidence, remain a top priority of treatment. 4 HISTORICAL ACCURACY IN REINTERPRETATIONFull understanding of upholstery materials and technology is critical to achieving a correct form if rebuilding or reupholstery is part of treatment. Upholstery conservation that goes beyond stabilization of existing materials requires historical knowledge, especially if the missing parts are to be put back in a historically accurate way. Rebuilding upholstered areas requires specialized skills in upholstery. These skills and an understanding of the upholstery process become critical in reconstructing an under-upholstery, especially from alternative materials like plastics, if the curatorial demands of historically accurate forms are to be met. An object does not often retain enough information to enable conclusions to be drawn regarding form and fabric. Interpreting the aesthetics of the piece accurately and rebuilding an upholstered shape or choosing 5 TREATMENT5.1 TRADITIONAL METHODSFor some objects, traditional upholstery methods might be considered appropriate. A mid-19th-century piece, for example, may need traditional methods of attachment, such as relashing or support lashing of the springs, to keep all the materials together. New rows of stitching may be needed to support or reattach two or three layers of original stuffings. Traditional techniques can be a successful as well as convenient process in stabilizing upholstery materials. These methods, however, typically cause a great disturbance to the original fabric of the object and should be considered only after establishing that less intrusive methods will not reach the goals of the treatment. A new loose slipcover of a good reproduction fabric constructed using period methods can be an afforable solution and can cover a multiptude of sins. Figure 1 demonstrates how a new tight slipcase might work for a slip seat of a side chair.

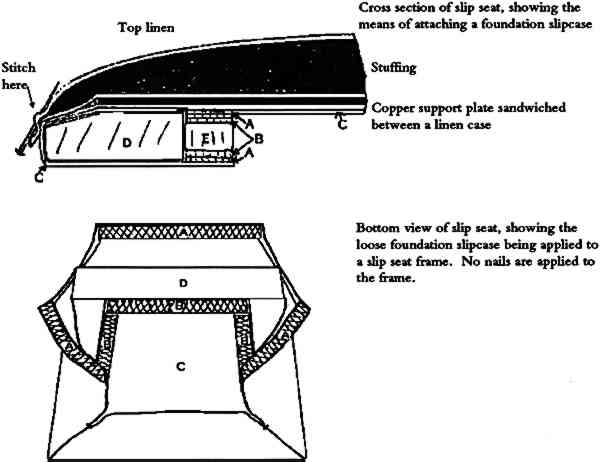

5.2 METHODS THAT USE FEW METAL FASTENERS: A FEW SOLUTIONS5.2.1 High-Density Expanded FoamsWhen the frame retains no upholstery layers, it is possible to construct an underupholstery from an alternative material. A high-density foam such as Ethafoam (expanded 5.2.2 Drop-In SeatsPlastic materials are not always suitable for use in seats because they are so hard. For comfort of a seat that is still being used, traditional materials are often required. A new seat frame can be constructed to fit inside the original frame so it is structurally sound enough to hold the weight of the sitter. Faced with a liner, it will not rub or bruise the period frame. The new frame can be used to hold the traditional materials of webbing, stuffing, and the hundreds of tacks required to secure the various materials of the reupholstery, but the period materials remain undisturbed. Figure 2 demonstrates how new materials can be used to hold upholstery layers and protect the artifact.

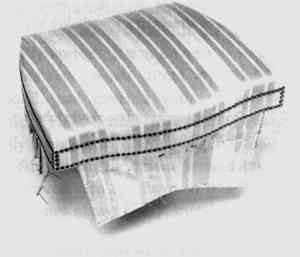

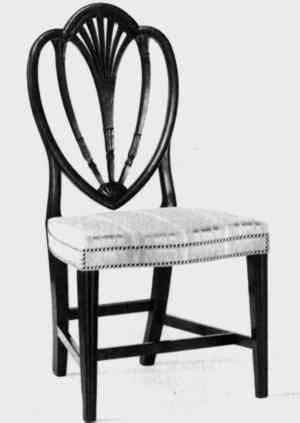

5.2.3 Caps and ApronsMany artifacts have endured losses to their wood edges from numerous tacks being applied and removed during successive reupholsteries. It is possible to face these edges with a ridged support rather than execute extensive replacement to the wood to regain strength and a proper form. These “aprons” of various materials, such as sheet polyethylene or thin sheet copper, can be covered with fabric so they have a sewing edge for the attachment of the finish cover or trim. The additional layers can also be adhered to the new support with a suitable adhesive. These aprons can be secured to a new seat frame, or they can be screwed into Ethafoam or possibly minimally stapled to the artifact, depending upon the needs of individual project. This method is especially useful in treating a piece where the upholstery goes half over the rail and finished show wood prevents wrapping the fabric around the rail. Aprons can easily become part of other noninterventive upholstery systems such as “caps.” The support system for the seating area can be constructed out of thin sheet copper or cast from man-made polymers and used as the base of the upholstered area. The cap is then built up with textile layers to complete the form. Figure 3 demonstrates how new materials can be used to fabricate an upholstered area that is entirely separate from the furniture. Figure 4 shows the end result of alternative upholstery methods on a period frame. The decorative brass nailheads are gluded on rather than driven into the frame.

5.2.4 AdhesivesAdhesives seem to be an obvious solution to holding materials in place where metal fasteners are undesirable. However, keeping the adhesive contained to the new materials while providing a clean line to the form of the object is a challenge. Heat-sensitive sheet adhesive like Beva film set onto materials that can maintain the characteristics of being thin, strong, and stiff, such as Nomex (a Du Pont polyamide product), can be used in the tacking margin to hold the finish fabric. The Nomex is heat set to the sheet adhesive (adhesive side up) and then laid onto the tacking margin and attached to the wood using a minimal number of metal 5.3 TEXTILE CONSERVATIONWhen original upholstery materials remain on the piece, some kind of textile conservation is usually required. It is important to preserve the under-upholstery layers with the same respect as the finish fabrics because of their importance as documents. 5.4 TEXTILE SOLUTIONSThe various elements in finish covers and trims required for historical accuracy in the reinterpretation can be prohibitively expensive to execute by traditional methods. An elaborate Chinese embroidery, for example, might cost thousands of dollars to reproduce. It might, however, be possible to capture the appropriate aesthetic using a different and more affordable technique such as silk-screening the design. The assistance of local craftspeople and artists to reproduce some of the delicate 6 SUMMARYUpholstered objects come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Furniture forms like chairs and sofas are the most familiar. Other forms such as trunks, sewing tables, state beds, and coaches with upholstered interiors share basic construction techniques of application of fabric layers and sometimes stuffings to some kind of frame. Each piece presents a unique challenge due to its elaborate construction and use of many different kinds of materials. The finish fabric can be an artifact in itself. The techniques that hold all these materials together are also of historical importance. There is a great deal to be learned from historic upholstery. Each object contains evidence of the technologies of the time it was made. Each is often a valuable social document as well. Options in treatment range from examination and documentation for scholarship purposes to elaborate noninterventive methods which use no fasteners that penetrate into the artifact and can take hundreds of hours to execute. Developing a treatment plan requires broad experience in many related areas, and it is common practice to consult with colleagues to resolve unanswered questions. Inquiring about the philosophy and approach used by others is a primary learning tool. Close attention to detail in observing period artifacts and in replicating historical detail during treatment is crucial to an honest presentation of an upholstered piece. With the increase of knowledge over the past decades, curators ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe author wishes to thank colleagues who contributed slides and descriptions of their work for the presentation in Buffalo and the preparation of this paper: Mark Anderson, Winterthur Museum; Nancy Britton, Metropolitan Museum of Art; David DeMuzio, Philadelphia Museum of Art; Carey Howlett and Leroy Graves, Colonial Williamsburg; Harold Mailand, Textile Conservation Services; staff of the conservation center at the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities; and the numerous institutions and private owners who generously agreed to using slides of their objects. Special thanks are due Deborah Trupin for her tireless efforts in pursuit of excellence for the Textile Update Session. FURTHER READINGAnderson, M.1988. A nondamaging upholstery system applied to an 18th century easy chair. AIC Wooden Artifacts Group preprints, New Orleans meeting. Anderson, M.1989. New applications of nondamaging upholstery. AIC Wooden Artifacts Group preprints, Richmond meeting. Chewning, C., and H. F.Mailand. 1993. Treatment of an American 19th century upholstered chair. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation32:119–28. Cooke, E. S., Jr., ed.1987. Upholstery in America and Europe from the seventeenth century to World War I. New York: W. W. Norton. French, A., ed.1990. Conservation of furnishing textiles. Postprints of Scottish Society for Conservation and Restoration conference, Burell Collection, Glasgow. Gill, K., 1988. Upholstery conservation. AIC Wooden Artifacts Group preprints, New Orleans meeting. Lahikainen, E., and A. W.Rollins. 1991. Upholstery conservation in the diplomatic reception rooms of the United States Department of State. Antiques (May): 811–19. Sands, J. O.1993. “An effect which far exceeds any conception”: An approach to conservation of a pair of Philadelphia arm chairs. Colonial Williamsburg15(3):72–73. Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities Conservation Center. 1990. Reupholstery of the Milwaukee Art Museum's Boston easy chair utilizing a new upholstery technique. Video, VHS. 18 mins. Trent, R.1991. The Wendell couch. Maine Antiques Digest (February):34D. Trent, R., and A.Passeri. 1987. More on easy chairs. Maine Antiques Digest (December):1–5B. Twichel, J.1990. Noninvasive foundations for reupholstery. AIC Wooden Artifacts Group preprints: Albuquerque meeting. Walton, K.1973. The golden age of English furniture upholstery, 1660–1840. Leeds, England: Temple Newsam. Williams, M.ed.1990. Upholstery conservation. In Preprints of the Upholstery Conservation Symposium held at Colonial Williamsburg. East Kingston, N.H.: American Conservation Consortium. AUTHOR INFORMATIONELIZABETH LAHIKAINEN received her B.S. in textiles from Syracuse University in 1972. During a career in textile conservation she was awarded a Kress Foundation Fellowship for independent studies to pursue her interest in upholstery conservation. She has been active in this area of specialization for more than a decade and has traveled extensively to both lecture and study original materials relating to the subject. Formerly head upholstery conservator at the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, she is now associated with the Textile Conservation Center at the Museum of American Textile History in North Andover, Massachusetts. Address: 80 Federal Street, Salem, Mass. 01970.

Section Index Section Index |