U.S. CUSTOM HOUSE, NEW YORK CITY: OVERVIEW OF ANALYSES AND INTERPRETATION OF ALTERED ARCHITECTURAL FINISHESCONSTANCE S. SILVER, FRANK G. MATERO, RICHARD C. WOLBERS, & JOEL C. SNODGRASS

ABSTRACT—The U.S. Custom House, New York City, was completed in 1907 by the pre-eminent American architect, Cass Gilbert (1859–1934). The building is recognized as an American masterpiece of integrated architectural design, engineering, sculpture, decorative arts, mural paintings, and decorative interior finishes. The U.S. Custom House is a designated National Historic Landmark and New York City Landmark. Largely abandoned in 1972, the structure has been undergoing complete renovation since 1991, including the conservation and restoration of the interior.This paper is an overview of the analyses of the original interior finishes and architectural polychromy, executed from 1910–12 by the artist-decorator Elmer Garnsey (1862–1946). These analyses served as the foundation for the program to conserve the surviving finishes and replicate the heavily damaged and almost completely overpainted architectural polychromy. However, Garnsey's execution techniques were so complex and the alteration and obfuscation of component materials were so extensive over time that the original appearance of the finishes is not definitively understood. Optical microscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), scanning electron microscope—energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and fluorescent dye staining indicated complex wet-into-wet pigmented and nonpigmented layering systems that combined oil, resin, and protein-carbohydrate media. Archival research on Garnsey supported the results of the analyses. The often perplexing data from these analyses strongly suggest unorthodox finishes and raise questions regarding the current practices of investigation and replication of architectural finishes and the appropriate professional skills needed for the restoration of historic interiors. 1 INTRODUCTIONThe U.S. Custom House at One Bowling Green in Manhattan (fig. 1) was designed by the pre-eminent American architect, Cass Gilbert (1859–1934) for the administration of customs duties collected from the Port of New York. Seven stories high and occupying a small city block, the building was the largest and certainly the most palatial of its type. It embodies the essence of Beaux-Arts traditions in its siting, plan, and elaborate decoration, while meeting the necessary requirements of a functioning office building.

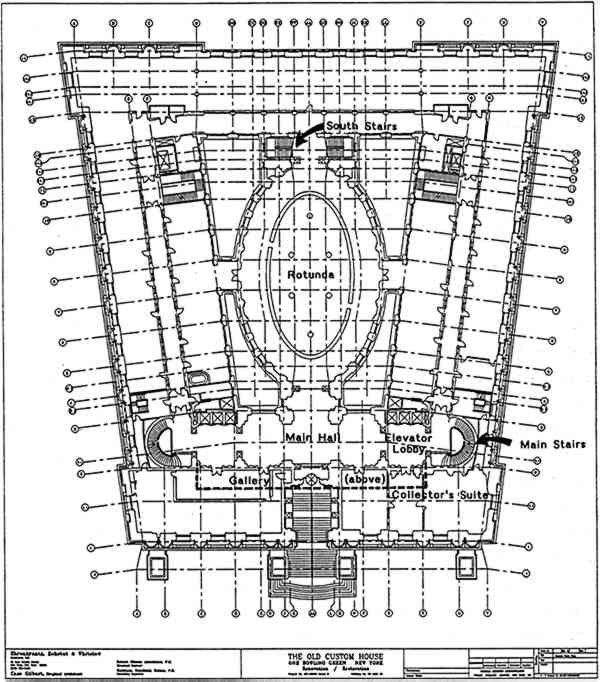

Gilbert's design is a masterpiece of integrated architecture, engineering, sculpture, mural painting, and decorative arts. The exterior sculptural program was conceived and executed by Daniel Chester French (1850–1931) with Adolph Weinman, Karl Bitter, and other prominent sculptors. The Tiffany Studios executed the decorative woodwork. The mural paintings, decorative finishes, and architectural polychromy were designed and executed by Elmer Garnsey from 1910–12 in The U.S. Custom House suffered destructive alterations while in use, including early and almost complete overpainting of Garnsey's original architectural polychromy and finishes. The building was largely abandoned in 1972 when the U.S. Customs Service moved to the new World Trade Center. In 1991, the renovation and restoration of the major public spaces of the Custom House began. The process includes the conservation of all surviving original mural paintings and finishes, the replication of the architectural polychromy, and the restoration of the elaborate metalwork and sculpture. The building is now shared by the National Museum of the American Indian of the Smithsonian Institution and Federal Bankruptcy Court. This paper focuses on the examination and analyses of Garnsey's original decorative finishes and architectural polychromy. This research served as the foundation for the conservation of intact finishes and the reproduction of lost finishes. However, the original execution techniques were so complex and unusual that an exact understanding of the precise physical nature and original appearance of Garnsey's finishes is somewhat elusive. The analyses were greatly complicated by the changes in and illegibility of the finishes due to physical and chemical alterations, damage from maintenance practices, and heavy overpainting. Nevertheless, investigations and analyses did reveal that Garnsey used only five base colors (see section 3.1) for the architectural polychromy of the public spaces throughout the building, often in combination with tinted glazes and scumbles. Both the tones of the five base colors and the glazes had obviously altered, assuming a darker, “mud To ascertain Garnsey's intended colors and surface finishes, detailed on-site examinations, scientific analyses, and archival research were required. The often perplexing results indicate combinations of the five base colors, imitative finishes that suggest marbling, and tinted glazes, all in tonal and textural coordination with the multicolored marbles, breccias, and patinated metalwork of the interiors. The following sections summarize the methodological approach developed for the investigation and replication of Garnsey's lost finishes.1 2 OVERVIEW OF ORIGINAL ARCHITECTURAL FINISHESBy 1990, Garnsey's original decorative painting was visible in only five areas of the building (fig. 2). Although deteriorated, the surviving finishes revealed the complexity of Garnsey's technical skills and decorative vision. The monumental main hall, apparently inspired by the Borgia apartments of the Vatican, is embellished with richly colored marbles and breccias in tones of cool gray, green, yellow-ocher, red, and mauve. The vaulted ceiling (fig. 3) is composed of four principal decorative elements on a canvas support: intricate low-relief pastiglia that

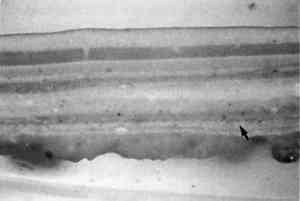

The Collector's Suite, adjacent to the main hall, has survived largely intact, and it is a lexicon of American decorative finishes for the early 1900s. The richly decorated coffered ceiling and the cornices and frames of the walls are oak-grained and gilded plaster toned with several different types of tinted and stippled glazes. The lunettes of the coffers are painted in mauve and teal green oil paints, the latter colored with a dye.2 The lunettes are finished with slightly pigmented glazes. The background of the gilded and glazed dolphin frieze is blue paint that has been “antiqued” with a brown scumble. In contrast, the decorated ceilings of the elevator lobbies on the third floor have been completely overpainted, with the exception of the low-relief pastiglia border. This border is painted in two shades of gray paint, with details in gold leaf. Both paint and gold leaf are covered with a toned stippled glaze. The groin-vaulted and barrel-vaulted gallery of the third floor opens onto the vaults of the main hall. The walls of the gallery are embellished with canvas panels that incorporate several different decorative motifs in low-relief pastiglia that is gilded and toned with various tinted glazes. The pastiglia has survived largely intact, but the panels were overpainted brown. Exposures on site indicated that the original finish of the wall panels was a mauve field with a green border. The fields and borders were originally toned with tinted glazes. Overpainted brown, the barrel vaults originally were painted in two shades of gray and toned with tinted glazes. Only the groin vaults survived intact. Although less complex, their finishes resemble those of the blue polygonal panels of the vaults of the main hall. Isolated concealed areas of the ornate plasterwork of the rotunda had escaped overpainting and suggested that Garnsey's finishes in the rotunda were a pale yellow base paint toned with a stippled rose-colored 3 ANALYSES OF THE ORIGINAL POLYCHROMYThe inherent difficulties in determining the original colors and finishes of heavily damaged and overpainted architectural surfaces have been understood for many years (Johnston and Feller 1967; Miller and Phillips 1976; Johnston-Feller and Bailie 1982). The often unorthodox use of media and colorants, the use of inexpensive or poor-quality materials, blanching and fading from ultraviolet exposure, “bleed-through” of media from layers of overpaint and decades in darkness under overpaint, all contribute to darkening, yellowing, alterations of tone, and sometimes total mechanical failure of the finishes. To address these adverse conditions, a multistep process of examination, analysis, and synthesis is critical to the definition and interpretation of architectural finishes. Seven principal steps can generally be anticipated in order to determine, with a good degree of certainty, the original appearance of polychromy and finishes: (1) archival research that might provide information on the original design, aesthetic objectives, materials, and techniques of the finishes; (2) sampling and microscopical examination of full stratigraphies from every major element, followed by initial color matches to a standardized system, such as Munsell, or possibly chromometric quantification using spectrophotometry; (3) exposure of the original surfaces by mechanical or chemical means and initial matches to a standardized system; (4) qualitative and quantitative analyses of colorants and media to support identification of the intended color and gloss; (5) development of an initial palette based on these data; (6) probable adjustment of the colors of the initial palette; and (7) a mock-up (e.g., a model panel) of the final palette and finishes on a large wall area in situ under final lighting conditions. The process must be repeated for the glazes and scumbles. All seven steps were required in the U.S. Custom House. 3.1 RESULTS OF INITIAL ANALYSES OF ORIGINAL POLYCHROMYHundreds of mounted cross sections from throughout the building were examined using reflected light microscopy, despite the inherent difficulty posed by the very thin, friable, and discontinuous state of the degraded and overpainted original finishes (fig. 4).4 A consistent stratigraphy was evident: (1) the plaster support of the walls; (2) an assumed size on the plaster; (3) a buff-toned primer; (4) the base paints (restricted to five colors); and (5) at least 10 layers of overpaint.

The five base colors of Garnsey's palette initially were identified descriptively as mauve, apple green, cream yellow, light gray-green, and dark gray-green. However, when matched to Munsell colors and then made up as an initial palette, a distinctly “muddy” tonality was perceived in all five base colors. Alteration of the original base colors and known surface finishes, such as glazes, was posited, prompting additional research, examination, and analysis. 3.2 ARCHIVAL RESEARCHSeveral documents written by Garnsey provided insights into his technical expertise and highly developed aesthetic vision.5 In his proposal entitled “United States Custom House, New York City, Description of Decorative Painting,” dated May 5, 1911, Garnsey wrote:

Garnsey also described the ceilings of the elevator lobbies and the gallery:

In a letter of March 19, 1912, to Gilbert, Garnsey proposed the decoration of the main stairwells:

These documents indicate that Garnsey intended the architectural polychromy to chromatically reference the distinctive tones of the multicolored marbles and breccias used throughout the building. This hypothesis was confirmed in part when the unusual mauve and apple-green base tones were exposed on the wall panels of the gallery. They matched the mauve and apple-green base tones that had survived intact on the vaults of the main hall. These mauve Thus, it was posited that the predominant color used throughout the Custom House, initially identified as a “light gray-green” in cross sections and exposures, originally was a true “stone” gray that referenced the gray-toned marble wainscot used throughout the building—exactly as Garnsey had described. This hypothesis was supported when analyses of the colorants identified only lead white and a small amount of carbonaceous material, the constituents of a light gray. The surviving original ornament of the ceilings of the third-floor elevator lobbies were also executed in two shades of “cool” gray, providing further support. However, initial over-reliance on archival documents delayed recognition of the complexity of some of the finishes throughout the Custom House, especially those of the blue panels of the main hall and the blue groin vaults of the gallery. In 1990, visual examination of the blue panels, studies of cross sections, FTIR analysis, and analysis by fluorescent dye staining indicated a perplexing stratigraphy: (1) lead white preparation on the canvas; (2) pebble-textured blue base-paint composed of ultramarine and lead white paints; (3) application of one, perhaps two, tones of tinted glazes; and (4) a blanched protein-carbohydrate stratum overall.6 A 1915 description by Garnsey of a very similar decorative scheme in the library of the City Art Museum, St. Louis (now the St. Louis Art Museum) suggested the same materials and techniques of execution that characterize the decoration of the main hall of the U.S. Custom House (Garnsey 1915). Garnsey's 1915 description seemed especially applicable to the blue panels, in which the blanched stratum apparently was a pastelike material, intended to function as a matte-textured protective coating that could be removed easily with soap and water as it became soiled in urban environments. Garnsey wrote of his decorative finishes in St. Louis:

3.3 ADDITIONAL FLUORESCENT DYE STAINING AND FTIR ANALYSES OF SAMPLES FROM THE U.S. CUSTOM HOUSEFrom 1991 to 92, analysis and reanalysis of several samples of surviving original finishes and heavily overpainted finishes were conducted. Analysis of samples of the blue panels of the main hall indicated a technique of execution that differs from Garnsey's 1915 description of apparently similar finishes in St. Louis. In summary, the protein-carbohydrate material appears to have been worked into the blue base paint wet into wet rather than applied as a continuous surface coating. Thus, in a strictly sequential order, the toned glazes—composed of an oil medium and a resin medium—were the final application, but they were also worked wet into wet into the protein-carbohydrate material with a patterned tool (fig. 5).

Two researchers concluded independently that some finishes were executed as wet into wet multimedia composites, enhanced with tinted glazes in many areas.7 From these data, an intended marbleized effect was posited on some elements. Other finishes almost certainly were executed in emulsion paints, while others were standard oil paints. Analyses by fluorescent dye stains provided the following data: SAMPLE 1. Light gray-green paint, south stairwell. The entire layer stained positively for oil with rhodamine B (RHOB) uniformly; the bottom half reacted slightly with eosin isothiocyanate (EITC), a general protein stain. When stained with antimony pentachloride, the upper half did not react, while the lower half of the layer strongly reacted, indicating a resinous component in that portion of the film. This pattern of staining strongly indicates a phase separation on drying in the binding materials, such as an emulsion paint system. There was an unusual staining with antimony pentachloride on the surface of the layer, indicating a resinous component such as a varnish or glaze layer. SAMPLE 2. Mauve paint, wall panel, south stairwell. This paint stained positively for oil, carbohydrate, and protein (using RHOB, triphenyl tetrazolium chloride, and EITC) and must be considered an emulsion type of paint. SAMPLE 3. Dark gray-green paint, pilaster, south hall. The original surface appears to have presented a marbleized effect because there are three layers applied almost wet into wet. Layers 2 and 4 are colored the same and stain positively for oil and a resinous component, while layer 3, the actual dark gray-green, appeared to be only oil. SAMPLE 4. Mauve paint, rosette on pilaster, second floor. This paint stained positively only for oil. SAMPLE 5. Light gray-green paint, outer border, main stairwell. This paint stained for oil, carbohydrates, and trace amounts of proteins, indicating an emulsion. Slight staining with antimony pentachloride, observed near the surface, indicates a varnish or glaze. 4 CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLEMENTATIONIt was concluded that many of Garnsey's finishes throughout the vast U.S. Custom House were mixed-media composites of complex layered structures, designed to compliment, reference and harmonize with associated marbles and breccias and patinated metalwork. The surviving original blue panels of the main hall provide some sense of the luminous trompe l'oeil effect that was possible with Garnsey's complicated and esoteric admixtures of media. However, because the media of these surviving finishes have darkened and become somewhat opaque, it is not possible to ascertain precisely the original appearances of the finishes. Similarly, so altered, damaged, and overpainted were most of the original architectural surfaces that exposure of Garnsey's finishes proved impossible in most instances. Where exposed, extreme shifts of tone and darkening were obvious. Consequently, an exact replication of Garnsey's finishes was not judged possible in the U.S. Custom House. Rather, Garnsey's original five-color scheme for the architectural The complex nature of Garnsey's finishes, their alteration of tone and deteriorated condition, made determination of the five base tones and glazes a complicated process that required a minimum of seven steps. Historic architectural finishes are customarily examined in cross section using reflected light microscopy to determine color matches, sometimes in conjunction with exposures of original surfaces in the building and pigment analyses. However, incorrect colors and an incomplete and incorrect understanding of Garnsey's remarkable decorative repertoire would have resulted without an integrated approach and extensive examination of the decorative finishes (table 1). TABLE 1 GARNSEY'S PALETTE IN THE U.S. CUSTOM HOUSE: INITIAL AND FINAL IDENTIFICATION OF BASE COLORS The U.S. Custom House, like so many outstanding historic buildings, is a structural work of art on a vast scale that incorporates the same component materials, execution techniques, and conservation problems that characterize other works of art. The procedures used to determine Garnsey's polychromy and other decorative finishes were developed for, and continue to evolve for, fine arts conservation. Thus, the roles for conservators in historic preservation and restoration projects must be viewed as indispensable, but separate from, those of architects, preservationists, craftspeople, and construction managers. NOTES1. The 1990–92 renovation and restoration was under the jurisdiction of the General Services Administration (GSA), which retains overall responsibility for the building. The analytical program for the identification of the interior finishes described in this paper was carried out by Constance S. Silver, Preservar, Inc., under subcontract to Ehrenkrantz and Eckstut. Frank G. Matero, University of Pennsylvania; Richard C. Wolbers, University of Delaware; Joel C. Snodgrass; Robert Koestler and Frank Santoro, SciCon Associates, Inc.; and Richard Bisbing, McCrone Associates, all provided invaluable technical support. The 1991–92 interior conservation and restoration project was carried out by Evergreene Studios, with Perry Huston and Rustin Levenson supervising the conservation treatments. Constance Silver was a consultant to Evergreene Studios for the restoration of the gallery, including confirmation of the five base colors and glazes. Several aspects of the analytical work described in this paper were also finalized during the 1991–92 project, in consultation with Richard Wolbers. Three historic rooms to be used by the Smithsonian Institution were studied under a different program. NOTES2. In March 1991, six samples of finishes from the ceiling and dolphin frieze of the Collector's Suite were examined by Richard Bisbing, McCrone Associates, using electron microprobe to deter NOTES3. After executing the murals of the rotunda in 1937, Reginald Marsh repainted all the adjacent architectural plasterwork of the dome. He attempted to replicate the tone of Garnsey's original finish. The closest Munsell match for the color applied during the 1991–92 restoration is 10YR 5.5/4. NOTES4. Joel Snodgrass carried out primary stratigraphic analyses of the cross sections by reflected light microscopy using a variable stereo-zoom binocular microscope with a fiber-optic light source and daylight blue filter. These analyses established the chromo-chronologies of the architectural spaces, which were then examined and confirmed by Frank Matero and Constance Silver. NOTES5. Garnsey's documents regarding the U.S. Custom House are in the Cass Gilbert Archives of the New-York Historical Society, New York City. NOTES6. In 1990, Constance Silver and Frank Matero examined the blue panels visually and by cross sections. SciCon Associates, Inc., analyzed the pigments by microscopy and EDS and the organic media by FTIR and fluorescent dye staining. They suggested from the resulting data that an oil medium may well have been applied over a resin medium in the “glaze” layer, but the final layer was identified as a gluelike material because it tested positively for protein. Also in 1990, Richard Wolbers examined one small sample of a blue panel by fluorescent dye staining. The resulting data appeared to confirm the results of SciCon Associates, Inc. NOTES7. An initial study of the U.S. Custom House was carried out in 1981 as a joint undertaking of the firms of Polschek and Breuer. At that time, Frank Matero posited a possible marbleized treatment of the light-toned grays as the predominant finish of the gallery through analyses of cross sections and exposures of finishes on site by cratering (revealing the stratigraphs on the wall). Matthew Mosca identified glazes on some base tones of the main stairwells. In 1991, Richard Wolbers posited a marbleized treatment on some elements and confirmed the glazes of the main stairwells. Additional studies of cross sections in 1991 by Joel Snodgrass using microchemical spot testing, polarizing light microscopy, and UV fluorescent polarized light microscopy further confirmed these findings. Additional FTIR and fluorescent dye staining by Richard Wolbers in May 1992 revealed the compositional and stratigraphic construction of the blue panels. In 1992 Snodgrass and Silver identified a blue-toned glaze on the light gray finish of the gallery (excluding the barrel vaults) by scanning several samples microscopically from different angles. However, the blue glaze was so degraded, essentially reduced to particles of ultramarine, that its original appearance could not be defined with any certainty. Thus, it was not recommended for execution as part of the 1992 restoration. NOTES8. In the course of the 1991–92 interior restoration of the U.S. Custom House, the decorative program described in this paper was executed only in the gallery and the third-floor elevator lobbies. REFERENCESGarnsey, E. E.1915. A new mural decoration by Elmer E. Garnsey. International Studio57: supp.ix–x.

Johnston, R. M., and R. L.Feller. 1967. Optics of paint films: Glazes and chalking. In Application of science in examination of works of art, Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. 86–95. Johnston-Feller, R., and C. W.Bailie. 1982. An analysis of the optics of paint glazes: Fading. In Science and technology in the service of conservation. London: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, Washington D.C.180–85. Miller, K. H., and M. W.Phillips. 1976. Paint color research and restoration of historic paint. The Association for Preservation Technology, Publication Supplement. AUTHOR INFORMATIONCONSTANCE S. SILVER is a conservator in private practice specializing in the conservation and restoration of historic interiors and focusing on mural paintings and decorative painted surfaces. She is trained in both fine arts and architectural conservation. She has an M.F.A in conservation from the Villa Schifanoia, Florence, Italy, and an M.S. in historic preservation from Columbia University. She was a staff member of the International Center for Conservation, Rome, for three years. She has participated in and directed many architectural conservation and restoration projects. She was an assistant to Bernard Rabin for the conservation of the mural paintings of the rotunda, U.S. Capitol Building, and she has directed the conservation of the murals of the principal public spaces of the Supreme Court of the State of New York, New York City, during the last five years. Address: Preservar, Inc., 949 West End Ave., New York, N.Y. 10025. FRANK G. MATERO is associate professor of architecture in historic preservation and director of the architectural conservation laboratory, University of Pennsylvania. He received his B.A. from the State University of New York at Stony Brook, and his M.S. in historic preservation from Columbia University, and he completed the certificate program in conservation, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. From 1981–90 he was assistant professor and director of the Center for Preservation Research, Columbia University. Address: Graduate Program in Historic Preservation, Graduate School of Fine Arts, 115 Meyerson Hall, Philadelphia, Pa. 19104–6311. RICHARD C. WOLBERS is an associate professor in the art conservation department, University of Delaware. He teaches both conservation science and painting conservation techniques in the jointly sponsored master's degree program at the Winterthur Museum/University of Delaware. Wolbers received a B.S. in biochemistry from the University of California, San Diego, in 1971 and an M.F.A. in painting from the same institution in 1977. In 1984 he received an M.S. in art conservation from the University of Delaware. His research interests include development of applied microscopical techniques for the characterization of paint media and binders and cleaning systems for fine arts materials. Address: Art Conservation Department, 303 Old College, University of Delaware, Newark, Del. 19716. JOEL C. SNODGRASS received an M.S. in historic preservation (architectural conservation) from Columbia University and an A.S. in building construction from Dean Junior College. He was staff conservator at the Center for Preservation Research, Columbia University. Currently, he is research coordinator-architectural conservator at the Architectural Conservation Laboratory, University of Pennsylvania, and maintains a private practice. Address: 241 Dover Rd., Manhasset, N.Y. 11030–3709.

Section Index Section Index |