CAN THE COMPLEX BE MADE SIMPLE? INFORMING THE PUBLIC ABOUT CONSERVATION THROUGH MUSEUM EXHIBITSJERRY C. PODANY, & SUSAN LANSING MAISH

ABSTRACT—The growing public interest in the processes and principles of conservation has led to the encouragement of numerous educational efforts on the part of conservators, institutions, and professional conservation organizations such as the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC). In response to this interest and encouragement, the J. Paul Getty Museum mounted an interactive exhibition entitled Preserving the Past. This exhibition was a collaborative effort of the Antiquities Conservation, Education and Academic Affairs, and Antiquities Curatorial departments. In an attempt to introduce the visiting public to conservation principles, activities, and plans, Preserving the Past focused on conservation efforts applied to the museum's collection of ancient objects.The exhibition was divided into sections addressing conservation ethics and principles; scientific examination and analysis; treatment; and environmental control (including working models of seismic isolation mechanisms). The gallery was staffed continually by specially trained museum education staff and docents, called facilitators, who offered visitors access to more detailed written information, hands-on activities, and guidance through the exhibit. Approximately 12,000 people visited the exhibition during the seven months it was on view.This paper describes the efforts to establish guiding principles, and realistic and accessible approaches to presenting complex subjects such as conservation to the museum visitor whose prior knowledge, interest, and time may be limited. Exhibition planning, the philosophical precepts for the exhibition, the physical installation and design, and the evaluation of the final gallery format and its impact on the visitors are discussed. 1 INTRODUCTIONDuring recent years the public's interest in conservation of both our natural resources and our cultural heritage has increased. Practicing conservators welcome this interest and the opportunity to inform the public about the work and the guiding principles of their profession. A current priority of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works is to increase public awareness of the important functions of conservation. The benefits of such awareness efforts go far beyond the enlightenment of single individuals. Funding through federal, state, and local agencies can be influenced by heightening the concern of both individuals and private-sector leaders. When the public gains a clearer understanding of conservation, both private and public collections are scrutinized through more informed eyes and the need for their protection takes on increased importance. And of course, some are so inspired by what they learn that they decide to join the profession. As part of the effort to enhance public awareness, the Antiquities Conservation Department of the J. Paul Getty Museum, in collaboration with the Antiquities Curatorial and Education and Academic Affairs departments, set out to produce an exhibition entitled Preserving the Past that would explain the conservation principles and activities related to the museum's collection of ancient art. Since no activity in a museum is ever independent or done by one person and since any exhibition, regardless of theme or intent, requires a wide range of talents and abilities, a small planning team was assembled from the participating departments to define the goals and mechanisms of the exhibition. Ultimately, the effort also required the expertise of many other departments, including audiovisual, preparations, publications, and photo services. From the initial planning to the opening, the exhibition took about one year to develop. The budget was provided by the Education and Academic Affairs Department. The planning team's first task was to distill the basic precepts of the conservation profession and the myriad of choices a conservator must make with each action taken. What did the public already know about conservation? What did we wish to tell them, and in what order of importance? The plan rapidly expanded, and the complexities of the issues to be presented in a limited amount of space and time became the first and most substantial hurdle for the team. An attempt to present any conservation treatment in a condensed, easily accessible, didactic display is risky. Many, perhaps most, of the concepts that become second nature to working conservators turn out to be quite difficult to distill for consumption by a general audience. After all, it is often difficult to communicate these aspects to fellow professionals within the museum world, let alone to the completely uninitiated visitor. Our challenge was to come up with displays that would do more than just tell a varied audience what we do every day (not always an exciting story) or romanticize our roles by presenting only dramatic before-and-after shots of cultural salvation. Instead, we hoped to involve visitors in a deeper appreciation of what they were seeing or what they had not been aware of. Surveys at the Getty Museum have shown that visitors spend an average of two to three minutes in any one gallery. With this information in mind, we planned installations that would capture the attention of the public and engage them for a sufficient time to provide a brief overview of the conservation department's work. Recognizing that there are many different ways of acquiring knowledge, we developed interactive learning opportunities as well as traditional interpretive devises such as labels. Throughout the exhibition, several layers of information were available. The tone and format were relatively informal. There was no set agenda; visitors were free to choose those aspects that especially intrigued them. One of the strategies strongly supported by the Education and Academic Affairs Department in previous interactive exhibits was the use of trained facilitators, chosen from the museum education staff and a selected group of docents. The facilitators were stationed in the gallery at all times. Their main function was to interact with visitors, encourage their involvement in the displays, and answer questions or provide avenues by which visitors could obtain the answers. The facilitators also assured the It was to our advantage to center the exhibition around the conservation of antiquities. Such a focus allowed for a more unified and defined scope to both the technical and the philosophical precepts and, in the end, allowed more time to discuss the profession as a whole. It opened a clear avenue to explain “minimal intervention” and permitted an emphasis on efforts to preserve rather than restore. Preserving the Past was located in a gallery adjacent to the antiquities collection. This location allowed visitors to take what they had seen and quickly relate it to the collection as a whole. To present a logical flow of information, the exhibition was divided into four sections: Introduction, Scientific Examination, Treatment, and Environment. 2 EXHIBIT INTRODUCTIONThe introductory section described, in general terms, the profession of conservation. It immediately set the tone and gave the visitor a good foundation for understanding the rest of the exhibition. Ethical considerations and challenges regularly faced by working conservators were described, and an overview of the rest of the installation was given. The most effective component of this section, indeed of the entire exhibition, was a six-minute “behind-the-scenes” video filmed by the Audiovisual Department over a period of one year. The museum's antiquities conservators, mount maker, and interns were shown working on various projects, including the gap filling, inpainting, and mechanical cleaning of stone, bronze, and ceramic objects. Scenes of a seismic isolation mechanism being tested on a shake table at a commercial engineering firm were also featured. The video showed the apparatus, which is now used in the antiquities galleries, being run through a series of tests using a cement facsimile of a monumental fifth-century Greek statue. The tests approximated the movements of a powerful earthquake of the kind likely to hit southern California. To meet the needs of our Spanish-speaking visitors—a large and significant population in California—we provided a Spanish-language version of the video script. Judging from visitor responses to a survey we later conducted, the video, more than any other aspect of the exhibition, was quite successful in attracting and holding visitors' attention, giving them a glimpse of a facet of museum work that they might never see. 3 SCIENTIFIC EXAMINATIONThe second section of the exhibition stressed the importance of the thorough scientific examination of objects before treatment. To

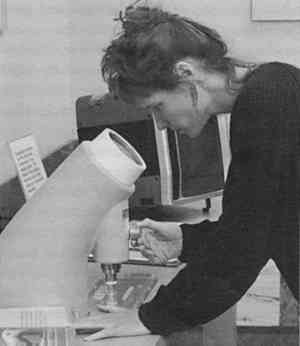

The problem of authentication of objects has gained a great deal of attention in the popular press, and the public is especially interested in how the identity and provenance of an object are verified. The exhibition offered an opportunity to clarify misconceptions about both the abilities and the limitations of technical and scientific investigation. A display of two ceramic vessels, one ancient and one a modern forgery, led visitors through a series of questions regarding their own perceptions and observations as to what signals authenticity and what indicates forgery. The answer to these questions and more detailed explanations were included in a notebook kept below the case. The techniques of thermoluminescence, ultraviolet inspection, and x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy were also described in the notebook. 4 TREATMENTThe section on treatment began with an interactive activity that involved two fragmentary reproduction vases. Visitors were invited to join broken pottery fragments and then identify the name of the vase from a chart of Greek vase shapes. We hoped this activity would give visitors an idea of the patience and manual dexterity that conservators need, but, more important, we wanted to help them make connections among all aspects of the exhibit. This activity could be criticized for encouraging a common public perception of conservation as an activity involving putting together old pots, but it proved to be an effective method of getting visitors interested in the subject matter of the exhibition. The vase exercise effectively introduced a display on ceramic conservation that described the step-by-step procedures a conservator may employ to complete the shape of a fragmentary vessel. The steps involved in the reconstruction of a Greek kylix cup were laid out in a horizontal case (fig. 2).

The treatment of ancient bronze and marble objects was illustrated by before-and-after color photographs of two portrait busts from the collection. Wall-mounted text panels amplified the philosophy behind the treatment as well as the treatment process itself. Further explanations and photographic documentation of mechanical cleaning techniques were located in the notebook on the podium below the wall display (fig. 2). Too often, people learn about conservation from the presentation of stunning, dramatic before-and-after views. This technique is an assured way to attract attention but an ineffective method of keeping it. The comparison of the conservator-object relationship to the doctor-patient relationship has tinged the profession with an often unrealistic, and certainly overly romantic, tone. The surgeon making a dramatic decision to operate, resulting in the patient's miraculous recovery, makes a better character in a novel than does the practitioner who advises on good diet and exercise. Yet in reality, and especially in our modern world, prevention is preferred over intervention, both in medicine and in art. In our exhibition, we tried to minimize the strong but overemphasized doctor-conservator analogy and raise other concerns more pertinent to modern preservation. 5 ENVIRONMENTA display of a cutaway microclimate exhibition case containing a bronze statuette introduced the section on the importance of environmental issues (fig. 3). The display exposed a variety of protective layers under the case build-ups that help maintain a stable and controlled environment. A duplicate mount and build-up illustrated how the statuette was held in place. A tray of silica gel and a digital hygrometer were also visible. An accompanying notebook

The oil and grime that can accumulate on art objects just by being touched was illustrated by a 4 in square piece of modern marble that had been exposed to handling for one year prior to the show's opening. This display prompted several visitors to say that they will no longer be tempted to touch objects in a museum after seeing the difference between the protected central area and the unprotected peripheral areas of the marble piece. Another environmental display evoked much reflection on the dangers that works of art face in the seismically active area of California (fig. 4). Two reproduction vases were mounted to a build-up over a small “shake” table that was constructed by the antiquities conservation mountmaking staff. One vase was mounted with the added protection of an isolation base. When the visitor pushed a button, the build-up in the case shook, simulating earthquake motion or other sudden trauma. The demonstration clearly showed that the isolation mechanism protected the vase from damage, while the other vase shook violently. Simpler methods of securing vases—for example, the use of dental wax to secure some vases on Plexiglas mounts—were pointed out in the adjoining vase display gallery.

6 SURVEY RESULTSDuring the last few weeks of the exhibition, the Education and Academic Affairs department conducted an informal survey of 125 visitors as they left the museum and did 38 in-depth interviews with people as they left the Preserving the Past exhibition. The facilitators also kept a log book in which they noted visitor reactions to the exhibition. As in any endeavor with a varied audience, some visitors found the exhibition not technical enough and wanted to know more, and others thought it was too technical. We had intentionally targeted the exhibition for adults because it was the audience we wanted to reach, but some expressed the desire to see the show geared more to children. Small children were very intrigued with the vase sherd exercise and the earthquake shake table. Preteens and teenagers were able to grasp much of the exhibition with curiosity and enthusiasm. Of the 38 visitors interviewed, most were able to discuss at least one of the principles of conservation highlighted in the exhibition with impressive accuracy. All expressed the desire to see more exhibits like this one on all facets of the conservation field. 7 CONCLUSIONSPreserving the Past encouraged much discussion, provided a great deal of information, and heightened awareness of the conservation field for a large and varied audience. We hope that many of the estimated 12,000 visitors, including school children, will approach their future visits to our museum and other museums with a new and enlightened outlook. Such exhibitions provide the public with a window through which they can view the complexity of the field, the decisions that must be weighed, and the development of solutions for the complicated problems that await us. We found that with careful and thoughtful planning, exhibition that open to view the world of conservation can in fact be made simple and understandable to a general audience. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe authors wish to acknowledge and thank the J. Paul Getty Museum Department of Education and Academic Affairs (Wade Richards and David Ebitz), Antiquities Curatorial Department (Karen Manchester), Preparations and Audio Visual departments (Bruce Metro and Stepheny Dirden), the Photo Services and Publications departments, as well as the staff of the Antiquities Conservation Department. SOURCES OF MATERIALSWentzscope (Easy View Microscope, Museum Edition)Budd Wentz Productions, 8619 Skyline Blvd., Oakland, Calif. 94611 Panel Mount Digital HygrometerEdmund Scientific Company, 101 E. Gloucester Pike, Barrington, N.J. 08007–1380 AUTHOR INFORMATIONJERRY C. PODANY has been head of the Department of Antiquities Conservation at the J. Paul Getty Museum since 1986. He lectures and teaches frequently on the subject of conservation and collections care at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of Southern California, where he is an adjunct professor in the School of Fine Arts. He received a certificate in archaeological conservation (with distinction) from the University of London. He is a Professional Associate of the AIC and a Fellow of the IIC. Address: J. Paul Getty Museum, P.O. Box 2112, Santa Monica, Calif. 90406. SUSAN LANSING MAISH graduated from the Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, California, with a bachelor of fine art in 1984. She interned at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art where she worked on its collection of historical silver. This led to a collaborative project on silver cleaning abrasives with Glenn Wharton of Glenn Wharton and Associates, Santa Barbara, California and William S. Ginell of the Getty Conservation Institute. She joined the staff of the Antiquities Conservation Department in 1986 and is an assistant conservator and a Professional Associate of AIC. Address: J. Paul Getty Museum, P.O. Box 2112, Santa Monica, Calif. 90406.

Section Index Section Index |