TEXTURED PANELS IN 19TH-CENTURY AMERICAN PAINTINGMARCIA GOLDBERG

ABSTRACT—The practice of texturing the support or ground of panel paintings has been attributed in the literature to Gilbert Stuart. His purpose was supposedly to simulate his favorite English twilled canvas, which was in short supply due to an embargo preceding the War of 1812. Examples of textured ground and support by other artists indicate the practice was not limited to Stuart. As these examples date at least through the first four decades of the 19th century, the scarcity of imported canvas probably was not the rationale for texturing panels. The literature on the artist Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828) includes a story about a cabinetmaker named Ruggles who textured the artist's panels to resemble twilled canvas. In some of Stuart's portraits on wood, this treatment can be seen in passages where the paint layers are thin (fig. 1). The technique evolved, according to the standard sources, because Thomas Jefferson's Embargo Act of 1807 cut off the supply of Stuart's favorite English canvas (Mason 1879; Mount 1964; Park 1926; Whitley 1932).

In the course of researching the early 19th-century artists Samuel Lovett Waldo (1783–1861) and William Jewett (1792–1874), I found a number of textured panels, all painted in the decades after the embargo acts preceding the War of 1812 had been lifted. These findings demonstrated that this special preparation of the surface of panels was not limited to the work of Gilbert Stuart and that it may not have been devised as a wartime exigency. This paper summarizes an investigation of these points. Panel paintings are not rare in Stuart's oeuvre. Among the works in which the support was known, they constitute roughly 20% of the portraits in the Lawrence Park catalog (1926). This is a very conservative estimate if compared with William Sawitsky's claim: “of about 800 portraits by Stuart which have come under my observation, I have found almost 300 to be on From the beginning of the 19th century, the flow of foreign goods to the United States had been constantly disrupted. The war between Britain and France, begun in 1793, had an immediate effect on neutral shipping. Accommodation with one belligerent led to confrontation with the other. By 1803, when hostilities resumed after a brief period of peace, nonpartisan trading vessels were again in danger of being seized by one of the warring nations for possibly providing material support to the other. Moreover, the British attacked neutral ships trading with the West Indies, especially those islands involved in trans-shipment of foreign goods to American merchants. Congress responded to the situation by passing a Non-Importation Act in 1806. The act excluded British articles that could be made in the United States or elsewhere. Among the items barred were manufactures composed wholly or principally of hemp and flax. By 1810, few domestic factories were spinning and weaving flax (Bishop 1866). At the end of 1806 the act was suspended until 1809. In the meantime, Britain's blockade of part of the European coast was followed by Napoleon's blockade of the British Isles. The immediate consequence was that all neutral vessels and their cargoes were liable to confiscation. Early in 1807, an American frigate was fired upon off the Virginia coast, and four of its seamen were removed and impressed into the British Navy. In response, all British ships were ordered out of American territorial waters, and the Embargo Act of 1807 was put into effect by the end of the year. This act prohibited American vessels from embarking for foreign ports. It did not restrict imports per se but because foreign carriers were not permitted to take American goods out, trade was essentially halted. The Embargo Act was supplemented in 1808 but repealed in 1809 and replaced by the Non-Intercourse Act, which renewed trade with all nations except Britain and France and forbade importation of their products. During these years normal shipping was seemingly curtailed, but some vessels did complete voyages, bringing desired imports to American shores. In addition, American merchants employed smuggling and other means of noncompliance. The fact that the greater number of portraits by contemporary artists were on canvas suggests painting materials were among those foreign manufactures that continued to be available (Nettels 1962; Jennings 1921; Harrington 1927). Foreign trade fluctuated between accommodation and restriction, depending on the cooperation of France and Britain, until April 1812, when President James Madison announced a new embargo. Two months later he asked for a declaration of war against Britain. It was an unpopular war with many in the maritime states, and illicit trade with the enemy continued. The Embargo Act passed late in 1813 prohibited While it is true that Stuart used wood more frequently during the years of the embargoes and the War of 1812, his use of panels had been increasing from the beginning of the century. Apparently, Stuart executed no portraits on panel during his stay in Ireland prior to returning to the States in 1792 (Crean 1990). Further, wood supports made up a significant fraction of his works after the war and through the 1820s, when more or less normal trade had been restored. Samuel Waldo, who settled in New York in 1809 after three years in London with Benjamin West, apparently did not use wood supports until about 1815, after the war. Panels are common among his works and those executed with his partner William Jewett in the 1820s. By far the largest number date from 1830–35, when 26 of 27 portraits that can be dated with some exactness are on wood. After 1837, the number of panels decreases sharply. A few were painted in the 1840s when canvas should have been readily available. At first an engraver and painter of miniatures, John Wesley Jarvis began concentrating on portrait painting around 1804. His response to fluctuations in foreign trade would seem to be more direct than Waldo's, as wood panels are prevalent in his works from 1809 to 1815 but are rare after the war. There are few panels in the work of Charles Bird King in the years immediately following his return to the United States from England in 1812. But in the early 1820s he began his series of Indian portraits, many of which were on wood. He continued to use panels through the 1830s, a period of high imports, and well into the 1840s. The earliest portraits on wood by Ezra Ames date from 1809. Twelve were painted between that date and 1826, near the end of his professional career.2 Use of wood supports by these artists might be related to the country's economic cycles as well as to fluctuations in foreign trade. There was a depression in 1808–09 while the embargo was in effect. A major economic downturn occurred after the war in 1815–21, overlapping the banking crisis and business failures of 1819–22. Various tariffs of the 1820s may have indirectly affected the importation of canvas. Another major depression covered the years 1837–43. Certainly, artists were affected by the country's financial health. Thomas Sully (1783–1872), commenting on the few entries he had made in his register of paintings (unpublished; in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania) for the year 1807, blamed the embargo for dampening expectations in New York. He returned to Philadelphia and offered to do 30 portraits at reduced prices. William Dunlap (1766–1839) reported in his diary that John Wesley Jarvis was advertising in late 1819 his “lower-priced wares to make an appeal to shrunken pocketbooks” (Dunlap 1965). About the same time, Samuel F. B. Morse (1791–1872) in Charleston, South Carolina, was reducing his fees and his standard of living. But relating the use of panels to economic cycles suggests that artists viewed wood as a cheap alternative. Wood was not among the lower-priced wares Jarvis offered in 1819. Nor did Thomas Sully and Ezra Ames record in their account books any difference in charge for wood or canvas supports.3 Mahogany, the wood of many panel paintings, The account of the cabinetmaker Ruggles inscribing Stuart's panels was first published by the artist's daughter Jane in 1877 (Stuart 1877). A cabinetmaker named Levi Ruggles living on Winter Street, as she had noted, did appear in the 1810 Boston city directory (De Lorme 1976). Though some other facts in Stuart's article about her father have since been discounted, the story of Ruggles and his method of “twilling” has persisted through subsequent monographs on the artist. These accounts imply Stuart consistently had his wood supports textured. However, there are panels with a smooth surface dated later than those that are textured, and there are panels in which the ground and not the support has been treated. In five Stuart paintings examined by conservators at the National Gallery of Art, the twilled surface was found to be in the ground layer.4 A sample of textured panels by other artists also shows patterning in the ground. Caroline Keck located a “twill effect” in the priming of two 1816 portraits by Ezra Ames, John Meads and Mrs. John Meads (Albany Institute of History and Art). The

In Samuel Waldo's panels and in those he painted with William Jewett, as in Stuart's panels, either the ground or the support is liable to alteration. The Independent Beggar (1819, Boston Athenaeum), Portrait of a Man (ca. 1829, Toledo Museum of Art), and Lady in a Dark Blue Dress (1835, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) all carry the pattern on the support. Man with a Cane of 1823 (fig. 3), Robert de Peyster (1828, National Gallery of Art), and Portrait of a Man of 1831 (fig. 4) have textured grounds. The dates of these few examples suggest there was no period when Waldo favored one surface over the other for texturing. Interestingly, Lady in a Dark Blue Dress, painted on a textured support, has several test patches of patterned ground on the reverse.

It may be that wood type determined whether the support or ground was to be treated. Among the Stuart paintings examined by conservators for this paper, the pattern occurs on the support in mahogany panels but on the ground in those of yellow pine. Both are hard woods. The same proved to be true for panels by Waldo and by Waldo with Jewett. (The number of examined panels by these artists is admittedly very small.) The portrait Mrs. James Swan by Christiana Swan (1808, private collection), copied from a mahogany panel of the same sitter by Stuart, is textured on its support of yellow poplar. Jane Stuart reported that her father's cabinetmaker cut teeth in a plane-iron and dragged it backward, which proved “the best way of indenting without tearing the wood.” Supposedly, Stuart's panel Mrs. James Swan was textured in this manner. An x-radiograph detail (fig. 5) reveals the satisfactory

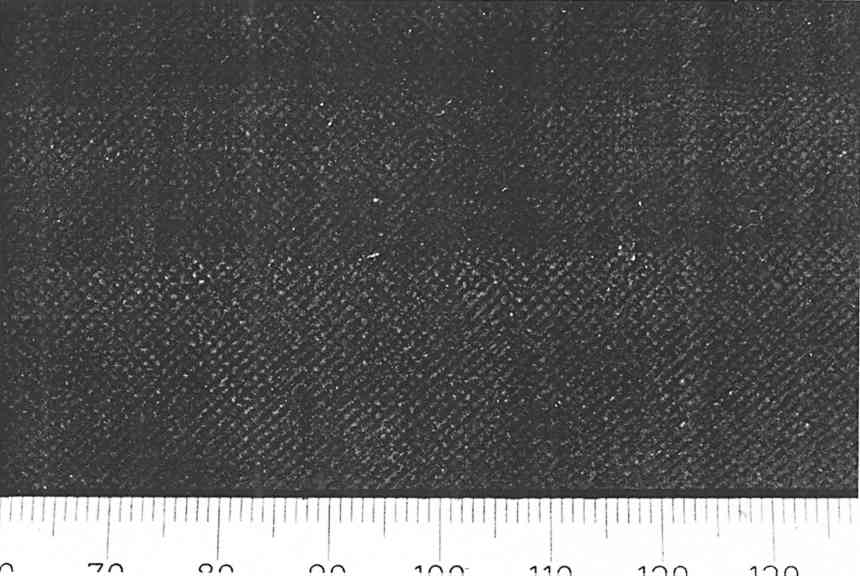

Some ground patterns have the appearance of fabric as if a woven material was pressed into the surface. The detail of the Princeton portrait by Waldo (fig. 4) shows a tight tabby weave, described by conservator Norman Muller as “too regular and consistent for an instrument. The lines and cross lines are a little less than a millimeter in width; the trough .2 or .3 mm in width. The whole runs on a diagonal across the panel.” The presence of slubs in the texture of this portrait and wrinkles as in the portrait Mary Fellows Penfield (unknown artist, ca. 1810, Historical Society, Penfield, N.Y.) further suggest a cloth mold. A closely woven fabric impressed on a pliable substance similar to ground, like putty or clay, does produce a clean pattern without ragged troughs. As the texturing is not visible over the whole panel but only in those areas that Other grounds exhibit a different effect. The pattern in the portrait Commodore Joshua Barney(fig. 6) is described by conservator Sandy Esterbrook as being combed. Conservator Lisa Mibach suggested that a suitable implement for this kind of texturing may have been a toothed finishing tool used for the initial removal of excess wet plaster.

Charlotte Hale of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's paintings conservation department thought the tool might be a roller. From examination of textured panels by Waldo or by Waldo and Jewett in the museum's collection, she observed that the pattern often ran in several directions rather than in a definitive single diagonal, as in Old Pat, The Independent Beggar(fig. 7). Michael Heslip of the Williamstown Regional Art Conservation Laboratory informed me that a pair of portraits on panel by Waldo and Jewett at Williams College—Rev. Edward Griffin and Mrs. Edward Griffin, apparently painted at the same time and scored before the ground was applied—are textured differently.

The textures of the Stuart paintings at the National Gallery of Art are not limited to one orientation, either. Based on these portraits, Kate Russell of the conservation department proposed a tool between 2 and 2� in wide. It would seem an instrument of the same size created the pattern in Waldo's unfinished portrait of his wife (fig. 8).

It is possible, of course, that Stuart originated one or several of these techniques. Waldo, Jarvis, Ames, and others may have picked up the process while executing commissions for copies of Stuart portraits. However, according to the Dickson checklist of Jarvis works and my own catalog of Waldo paintings, both artists were texturing wood supports before they received commissions to copy Stuart panels. The earliest textured panel by Jarvis located for this study is Mordecai Myers ca. 1810 (fig. 2); for Waldo, it is Woman in a Red Shawl, ca. 1815 (Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University). The Stuart paintings owned and copied by Ezra Ames to improve his painting style were on canvas. It is possible, however, that Stuart's textured panels were among those he or his patrons exhibited and thus were seen and examined by other artists. The variations in technique, resulting in variations in the patterns, among the works examined suggests that each painter found his own means for achieving the effect of a textured surface. The textured surface had been of interest to artists in the past. Coarse canvas was sometimes preferred to finer weaves, and grounds that had been roughened by a brush, stippled, or granulated were valued for effect. Perhaps these altered surfaces in masterworks appealed to Stuart, Waldo, and others who had studied abroad and had been exposed to a variety of techniques. But if they had consulted 17th- and 18th-century manuals on painting methods for instruction in texturing panels, they would have found little. The prerequisite for panel work in the standard treatises was an ultrasmooth surface. Roughening the wood, when mentioned, was for the purpose of giving it tooth to hold the gesso layer (Hendy and Lucas 1968; Laurie 1911). Such preparation was not Stuart's concern in George Reignold(fig. 1). The textured mahogany panel has no ground. Conservator Mark Bockrath wrote me that “the pronounced pores of the panel are quite apparent throughout…. Much of the design … is thinly painted and appears almost as a stain on the unprimed panel.” From this description, Matthew Jouett's (1787/88–1827) comment on a Stuart portrait “begun on naked … wood” can be taken literally (Jouett 1939). Clearly, it was not out of technical necessity that Stuart had some of his panels textured. His cabinetmaker commented that the artist missed the rough surface of canvas, which was favorable to the sparkle of color. Yet it would be difficult to describe many of the textured passages in the works by Stuart and other artists examined in this study as livelier than the areas in which the patterning is hidden or absent. It is often visible in plain backgrounds of dull color applied with plain brushstrokes. As with its origin and method, the purpose of texturing has yet to be determined. What is evident is that applying a pattern on a support or ground of a panel painting was ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSI am most grateful to the following curators and conservators who generously gave their time and expertise in discussion or correspondence: Mark Bockrath, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts; Tim Burgard and Richard Gallerain, New-York Historical Society; Anne Clapp; Sandy Esterbrook; Charlotte Hale, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Michael Heslip, Williamstown Regional Art Conservation Laboratory; William Hutton, Toledo Museum of Art; Caroline Keck; E. Sherry McFowble and the conservation department at Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum; Lisa Mibach; Norman Muller, The Art Museum, Princeton University; Helen Mar Parkin; Bruce Robertson and conservators at the Cleveland Museum of Art; and Kate Russell, National Gallery of Art. NOTES1. A catalog of works by Samuel L. Waldo and William Jewett is in progress by the author. 2. The data presented on the use of wood supports by Stuart, Jarvis, King, Ames, Waldo, and Waldo and Jewett are based on entries in previously cited catalogs or checklists in which the support is known and a date is given or approximated. 3. Sully did not record the type of support used in his paintings in his account books, but specific portraits on wood can be compared with those on canvas of the same year. He did recommend oak and straight-grained mahogany as best woods for panels. Poplar he considered a “treacherous material and when used should be painted on the back and edges.” Sully noted that Stuart liked basswood and baywood which “does not split or is apt to wharp [sic].” “Incidents in the Life of Thomas Sully,” photocopy of unpublished manuscript (New York: Frick Art Reference Library), 205. 4. George Washington, ca. 1810–15; Thomas Jefferson, ca. 1810–15; James Madison, ca. 1810–15; James Monroe, ca. 1817; and John Adams ca. 1825. 5. Textured panels by Alvan Fisher, William Dunlap, and Raphaelle Peale, contemporaries of the artists mentioned in this paper, also have been identified. REFERENCESBishop, L.1966. A history of American manufactures from 1608–1860. 1898. Reprint. New York: Kelley. Bolton, T., and Cortelyou, I.1955. Ezra Ames of Albany. New York: New-York Historical Society. Cosentino, A.1977. The paintings of Charles Bird King. Washington: National Collection of Fine Arts. Crean, H.1990. Gilbert Stuart and the politics of fine arts patronage in Ireland, 1787–1793. Ph.D. diss., City University of New York. De Lorme, E.1976. Attributions and laboratory analysis in portraiture: The master and the student. American Art Review (March): 128, n. 23. Dickson, H.1949. John Wesley Jarvis. New York: New-York Historical Society. Dunlap, W.1965. History of the rise and progress of the arts of design in the United States, vol. 2. 1834. Reprint. New York: Blon. 490. Harrington, V.1927. New York and the embargo of 1807. Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association. 8(2):143.

Hendy, P., and Lucas, A.1968. The ground in pictures. Museum21(4):266. Jennings, W.1921. The American embargo 1807–1809. Studies in the Social Sciences8(1):41. Jouett, M.1939. Complete notes on painting from conversations with Gilbert Stuart in 1816. In Gilbert Stuart and his pupils, J. Morgan. New York: New-York Historical Society. 81–93. Laurie, A.1911. The materials of the painter's craft …. Philadelphia: Lippincott. Mason, G.1879. The life and works of Gilbert Stuart. New York: Scribners. Mount, C.1964. A biography of Gilbert Stuart. New York: Norton. Nettels, C.1962. The emergence of the national economy 1775–1815. In The economic history of the United States. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. 324, 329. Park, L.1926. Gilbert Stuart. New York: Rudge. Sawitsky, W.1932–33. Some unrecorded portraits by Gilbert Stuart. Art in America21(2):81. Stuart, J.1877. Anecdotes of Gilbert Stuart. Scribner's14(3):376. Whitley, W.1932. Gilbert Stuart. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. AUTHOR INFORMATIONMARCIA GOLDBERG received her B.A. degree from the University of Iowa and her M.A. in art history from Oberlin College. She is currently an affiliate scholar at Oberlin. She has published papers in art history journals on 19th-century American art and artists. The research on textured panels resulted from an observation made during her work on a monograph on the artists Samuel Lovett Waldo and William Jewett, portrait painters in New York City during the early decades of the last century. Address: 383 Elm St., Oberlin, Ohio 44074.

Section Index Section Index |