RECENT TRENDS IN BOOK CONSERVATION AND LIBRARY COLLECTIONS CAREMARIA FREDERICKS

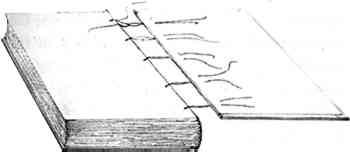

ABSTRACT—Preservation and conservation of library collections continue to develop in response to the overwhelming quantity of material in need of stabilization. In an environment of shrinking financial resources for both acquisition and preservation, continued user demand for access to collections places library materials at ever greater risk. In the area of rare book treatment, there has been a trend away from full treatment except when absolutely necessary. The development of simpler, less invasive treatment options has served both the desire to preserve more original material and the need to have greater impact on large collections. There is a greater focus on the use and deterioration patterns of objects or collections. Protective housing continues to be an important adjunct to and/or substitute for treatment. A broader range of treatment options is now available for non-rare collections, both within institutional programs and from commercial vendors. Concurrent with the broadening of options for preserving library materials in their original format is the exploration by the library community of many kinds of “reformatting” technologies for recording textual and visual information contained within bound volumes. Many of the new options in library preservation have come about thanks to increased communication between conservators and other library professionals. A more unified strategy has developed concerning the future of library preservation. 1 CONSERVATION TREATMENT OF MATERIAL IN ORIGINAL FORMATRecent trends in book conservation treatment can be characterized as much by an evolution in the conservator's approach to his or her work as by specific advances in technology or the introduction of new materials. Several factors, some of them familiar, have contributed to this development. Perhaps the most familiar and constant factor is the seemingly overwhelming quantity of deteriorating material in need of stabilization. Another constant but recently intensified condition is lack of adequate funding for preservation; growing collections must now be cared for with shrinking institutional resources. Compounding these problems is the relentless demand for the use of library materials, and use causes damage. As individual libraries have experienced cuts in acquisition funding and as cataloging information has become available on nationwide electronic networks, interlibrary loan activity has increased. Photocopying, which can literally destroy a fragile binding or a brittle book, takes place at such high volume that one conservator has described the library book of the '90s as a mere “accessory” to the production of copies (Frost 1991). While it gives the library conservator a heightened sense of purpose to be concerned with the preservation of materials people actually want to use, it is becoming more urgent than ever to devise conservation strategies that have an impact on as much of a given collection as possible, that make efficient use of financial resources, that match the treatment solution to the deterioration pattern of the item, and that target items at greatest immediate risk. This recent emphasis on productivity and cost-effectiveness does not mean that new treatment solutions are devised with less consideration for the artifact than has been traditionally employed in single-item conservation. On the contrary, the work of book conservators and preservation librarians over the last two decades has resulted in a much greater understanding of both book structure and book action on the part of both library professionals and preservation vendors. For example, librarian demand for flexible, durable, nondamaging bindings for circulating collections has led to the recent revision of the standards of the Library Binding Institute, while both in-house collections conservation units and preservation vendors have adapted conservation repair procedures to efficient, production-line work settings. At the same time, a growing desire on the part of conservators and librarians to preserve as much original material as possible has fostered an increasingly conservative treatment approach, especially for rare books. As Paul Banks pointed out in a widely quoted lecture in Austin, Texas in 1989, “authenticity cannot be restored.” Nearly every conservator I talked to prior to this session expressed a tendency to avoid extensive treatment unless a combination of frequent handling and poor condition dictates major reconstruction. Almost by happy coincidence, streamlined, less invasive conservation options have the double benefit of cost-effectiveness and the retention of more original material. Minimal structural repair and/or protective housing, often thought of as a first-phase stabilization of material slated for eventual treatment, is now quite likely to be chosen as an end in itself for rare materials receiving limited or controlled use, particularly when the authenticity of the binding structure is at stake. With this change in treatment approach comes a greater acceptance on the part of conservators and curators of a less “restored” appearance of certain objects after treatment; repairs are focused more than ever on restoring or improving aspects of function rather than appearance. One example of a recently developed repair technique that illustrates the trends described is the so-called board reattachment with joint tackets, (Espinosa 1991) in use at Brigham Young University for the repair of rare and nonrare leather-bound books whose boards are detached but are otherwise intact. (This technique is based on a repair devised by Anthony Cains, Trinity College, Dublin. [Cains and Swift 1988].) As an alternative to the potentially costly and sometimes overly invasive restoration technique known as rebacking, which involves replacement of missing areas of leather and tooling, the Brigham Young repair simply restores the function of the hinge area by lacing the boards back on using short loops, or tackets, of linen thread passed through small channels drilled into the shoulder of the text block and the spine edge of each board (fig. 1 and fig. 2). This repair can be performed in one to three hours, depending on the degree of aesthetic integration desired; the result is structurally sound and is accomplished with minimal disruption of extant original features. Similar solutions to this problem have been developed by David Brock and Don Etherington (Etherington n.d.).

2 PHILOSOPHICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN REFORMATTING OF LIBRARY MATERIALSThe new developments outlined above represent a significant broadening of available options for preserving library materials, both rare and nonrare, in the original format. Many conservators take it for granted that the original format—that is, the artifactual identity of an object—is inviolable; its preservation forms the raison d'etre of the field of conservation. However Preservation reformatting, in the form of black-and-white microfilm, was originally conceived to salvage information carried on pages too brittle to use or repair or to provide a surrogate-use copy of a fragile rare item. Lately, the process has taken on a much more complex purpose and identity linked with the newest preservation buzzword, “access.” The purpose of library preservation and conservation has in fact always been to prolong the useful life of books and documents or, in other words, to facilitate and promote reader access to information. However, certain kinds of reformatting can now enhance reader access to information far more than any individual book repair or protective housing. Microfilming creates masters from which an unlimited number of copy films can be made and then bought or borrowed by other libraries, thus eliminating the need to film any title more than once. Digital storage, while as yet unproven as a long-term preservation medium, has the potential for providing on-line access to extremely high-resolution scanned imagery, which can be printed out on demand at the individual computer work station. Stable technologies with accurate color reproduction are being sought to facilitate reformatting of materials relating to art and natural science. At the national level, reformatting programs are seen as the way to benefit the largest constituent group for the dollars spent. This view is due in part to the shared access reformatting can provide and also to the conviction that the preservation of information printed on brittle or potentially brittle paper is the most urgent national preservation need. At the request of Congress, the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) has focused its library preservation funding on projects to microfilm paper-based materials dating from 1800 to 1950. The Washington, D.C.–based Commission on Preservation and Access has also concerned itself almost solely with preserving “information” and Without denying the value and the appeal of new developments in reformatting technology, many preservation professionals have been disturbed by the seeming loss of stature of the original artifact (and the book format) in relation to the microform master and the digital disk. Once preservation dollars have been spent on creating a master in the new format, the original book or document, along with any associated binding, may be discarded or simply allowed to deteriorate, assuming it is not currently considered rare. This situation can be particularly distressing when reformatting projects are embarked upon for the stated purpose of “preserving” material in certain subject classifications, regardless of its present condition, on the assumption that embrittlement is inevitable and repair therefore not practical. While the “brittle book problem” certainly exists on a massive scale, there are also categories of material and types of damage for which repair or rehousing may be more appropriate as preservation solutions than microfilming. Thanks to recent efforts on the part of preservation professionals to promote a balance between reformatting and physical stabilization, the NEH will now consider proposals that include repair and rehousing of original material in collections being microfilmed for the purpose of broadening access, and the Commission on Preservation and Access has recently formed a task force to consider a national strategy for preservation of “the book as artifact.” Another reformatting technology that has gained popularity in recent years with those preferring a low-tech, user-friendly replacement option for brittle books is preservation photocopy. Brittle pages are copied onto permanent/durable paper using an electrostatic copier that produces a stable, well-fused toner image. Color xerography can be used to reproduce color plates, sometimes with surprising accuracy. The photocopies are bound, and the new book placed on the shelf to be used and rephotocopied by patrons. If space allows, the original brittle leaves may be retained in the library as “leaf masters”; deacidification of the leaves may help to prolong their shelf life. The most obvious advantage of bound photocopies is their familiar book format. Most library patrons find microfilm reader/printers awkward to use and the film itself difficult to handle. However, from the access point of view, photocopy has the drawback that it replaces a single deteriorated volume with a single sound one in the same manner as does conservation repair. Shared access is dependent on the old mechanisms of repeated photocopying and interlibrary loan. On the other hand, photocopying does ensure access at the local level and is a valuable alternative for libraries and patrons whose technological capabilities are not sophisticated enough to allow them to take advantage of machine-readable formats or microforms. The issues surrounding reformatting of library collections are complicated, and this summary has covered them with a very broad brush. Many new avenues are being explored, and everybody involved with new imaging technologies and with library preservation has a slightly different set of concerns and goals. One consensus that does seem to be emerging is that a balanced library preservation program takes advantage of all available options, including repair, rehousing, reformatting, and mass deacidification, and that careful preselection of materials for each option is essential. Despite Book conservators are sometimes accused of being too precious in their desire to retain artifactual integrity, especially where general collections are concerned. However, as conservators, it is our lot in life to wave the flag of the artifact and to be cautious about embracing sweeping mass treatments that drastically alter the physical or chemical characteristics of the collections under our care. It is also our job to keep devising new and better strategies for preserving artifacts in original format, not for the purpose of supplanting reformatting, but so that when reformatting is chosen, it is chosen because it is the most appropriate preservation solution. 3 CONCLUSIONMany of the new options in library preservation have come about thanks to increased communication between conservators and other library professionals. The appointment of liaisons between the AIC and the American Library Association (ALA), is one example, as is ALA's Conservator-Curator Discussion Group which meets at ALA's annual conference. The Research Libraries Group, a consortium of academic and research libraries, increasingly invites conservators to participate in task forces and study teams relating to preservation and collections care. The growing recognition that librarians and conservators are actually part of the same professional group has resulted in greater understanding on both sides and has made a more unified strategy possible for the future of library preservation. 4 CONTRIBUTORSThomas Albro, Library of Congress Conservation Office; Paul Banks, Columbia University School of Library Service; Gillian Boal, University of California Libraries, Berkeley; David Brock, conservator in private practice, San Diego; Harry Campbell, Ohio State University Libraries; Robert Espinosa, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University; Don Etherington, Information Conservation, Inc.; Gary Frost, BookLab, Inc.; Karen Garlick, National Archives and Records Administration; Maria Grandinette, University of Michigan Library; Anne Kenney, Cornell University Library; Deirdre Lawrence, Brooklyn Museum Library; Martha Little, conservator in private practice, Santa Fe; Katharine Martinez, Winterthur Library; T.K. McClintock, conservator in private practice, Somerville, Mass.; Ellen McCrady, Abbey Publications; Debra McKern, Emory University Library; Jan Merrill-Oldham, Babbidge Library, University of Connecticut; Bill Minter, conservator in private practice, Chicago; Frank Mowery, Folger Shakespeare Library; Sue Murphy, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas, Austin; Joe Newman, New England Document Conservation Center; Barclay Ogden, University of California Libraries, Berkeley; Jan Paris, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina Library, Chapel Hill; Mark Roosa, Morris Library, University of Delaware; Anna Stenstrom, Conservation Department, New York Public Library; James Stroud, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas, Austin; Eileen Usovicz, Micrographics Preservation Service (MAPS); Dianne van der Reyden, Conservation Analytical Laboratory, Smithsonian Institution; Terry Wallis, Library of Congress Conservation Office; Michael Waters, CMI Custom Manufacturing; REFERENCESCains, A., and K., Swift. 1988. Preserving our printed heritage: The Long Room project at Trinity College, Dublin. Dublin: Trinity College. Espinosa, R.1991. Board reattachment with joint tackets. Unpublished manuscript. Etherington, D. n.d.Minimal intervention for preservation of collection problems: Split joints on leather bindings. Unpublished manuscript. Frost, G.1991. Originals and copies: Duplicity in library preservation. Unpublished paper presented at Columbia University School of Library Service Conservation Forum, New York City. BIBLIOGRAPHYAbbey, Newsletter. 1989. Saving art history. Abbey Newsletter13(8):148 Abbey Newsletter. 1990. The idea of a central depository. Abbey Newsletter14(4):69 Abbey Newsletter. 1990. Pat Battin replies to advocates of repair funding. Abbey Newsletter14(2):25 American Archivist. 1990. Special preservation issue. American Archivist53(2): entire issue. Banks, P.1989. The nature of research library collections. Comments at NISO Subcommittee R meeting, Austin, Tex. 12 May. Unpublished typescript. BookLab, Inc. n.d. BookLab booknote 3: Collection maintenance repair for publishers' cased books. Austin, Tex.: BookLab, Inc. Commission on Preservation and Access. 1989. Progress report. Washington, D.C.: Commission on Preservation and Access. Commission on Preservation and Access. 1990. Selection for preservation of research library materials. American Council of Learned Societies Newsletter2(3):10–12. Frost, G.1989. Quick, cheap, good: Library collection conservation, a viewpoint from BookLab, Inc. Paper presented at Columbia University School of Library Service. Gertz, J.1990. Letter to the editor. Abbey Newsletter14(2):30. Kulp, L.1990. Letter to the editor. Abbey Newsletter14(2):13. Library of Congress. 1991. Library announces book preservation plans: Status of the mass deacidification program. Library of Congress Information Bulletin50(9):162. LITA. 1991. Emerging technologies interest group. Library and Information Technology Association Newsletter12(2):13. McCorison, M.1989. Statement on conservation, made to the Commission on Preservation and Access. Abbey Newsletter14(5):84. McCrady, E.1990. Preservation issues at ALA Chicago. Abbey Newsletter14(5):77–78. McCrady, E.1990. Deacidification vs microfilming. Abbey Newsletter14(6):112–13. McCrady, E.1991. ALA midwinter in the Windy City. Abbey Newsletter15(1):1–2,4. NEH. 1990. Preservation programs, guidelines and application instructions. Washington, D.C.: National Endowment for the Humanities, Office of Preservation. Ogden, B.1989. On the preservation of books and documents in original form. Report for the Commission on Preservation and Access. Abbey Newsletter14(4):62–64. Parisi, P., and J., Merrill-Oldham, eds.1986. Library Binding Institute Standard for Library Binding. Rochester, N.Y.: Library Binding Institute.

Waters, P.19861990. Phased preservation: A philosophical concept and practical approach to preservation. Special Libraries81(1):35–43. AUTHOR INFORMATIONMARIA FREDERICKS received a B.A. in art history from Swarthmore College in 1978. She began her conservation training in 1981 at William Minter Bookbinding and Conservation in Chicago while working at the Newberry Library bindery. She later served internships at the Folger Shakespeare Library, the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, and the Library of Congress. She has worked as a rare book conservator at the Library of Congress (1986–89) and at the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts (1989–90). She is currently associate conservator for library collections at Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library and an adjunct assistant professor in the University of Delaware/Winterthur Art Conservation Program. Address: Conservation Division, Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library, Route 52, Winterthur, Del. 19735.

Section Index Section Index |