“ACCESSORIES OF HOLINESS”: DEFINING JEWISH SACRED OBJECTSVIRGINIA GREENE

2 HOLY OBJECTSThe first category of ritual objects is called tashmishey kedusha, “accessories of holiness” or “objects which carry holiness.” The classic example is a Torah scroll. This is so obvious that it is not even mentioned in the texts. The category also includes:

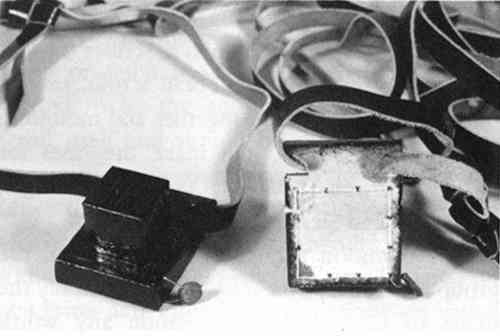

The three written texts, the Torah scroll, tefillin, and klaf for the mezuzza, form the core of this category. All are, or contain, biblical texts that must be handwritten on parchment, in a The common feature of the objects in the group is that they contain words, specifically the name of God, but by extension any words divinely written or inspired, from which the quality of holiness is derived. The nontextual objects all come into intimate contact with the texts, and in so doing acquire some of the same quality of holiness. The transmission is not indefinite, however, extending a maximum of two layers. For example, curtains located outside of the ark curtain itself are not affected. Over the years, this category has been expanded to include not only other handwritten biblical texts (such as the Scroll of Esther) but also printed Bibles, prayer books, volumes of the Talmud, law codes, and commentaries, not only in Hebrew but in other languages as well. In some communities, any document of any kind written in Hebrew letters was included; the holy quality of the Hebrew language extending to other languages, such as Yiddish, written with the same alphabet. According to the Shulchan Arukh (see note 1), tashmishey kedusha, when no longer fit for ritual use, must be “put away” (O.H. 154.3; Mishneh Torah, II 10.3). Traditionally, Ashkenazic Jews fulfill this requirement through burial, either in a specific part of a Jewish cemetery or, in some localities, next to or along with a man of exceptional piety and learning. Many Sephardic/Oriental Jewish communities put tashmishey kedusha in a special room in the synagogue, called a geniza (from the root meaning “conceal,” “hide,” or “preserve”). Because of the extension of the category to include handwritten and printed books and documents along with the traditional items, these storerooms often contained a great deal of material. The most famous geniza is in the Ezra Synagogue in Cairo. Rediscovered at the end of the 19th century, it held more than 200,000 pages, some dating to the founding of the synagogue in 882 (Milgram 1971; Encyclopedia Judaica 1971), 7:404. Once tashmishey kedusha have passed out of the traditional community and into the care of a museum, they can be further divided into two groups: (1) Torah scrolls, tefillin (both cases and texts), and the scroll (klaf) inside the mezuzza; and (2) all other material, including printed or handwritten documents, Torah mantles, ark curtains, tefillin bags, Torah ornaments, and mezuzza cases. Objects in group (2) may be treated by any qualified conservator. In all cases it is preferable to treat Jewish ritual material as anthropological material rather than as art, keeping conservation treatment to a minimum and avoiding extensive restoration, but any ethical treatment is permitted. Conservators in private practice, who may not have the option of minimal treatment, may have to take on greater responsibility as a result. Original fabric or trimming removed from an ark curtain, for example, should be given to the owner for proper disposal. If the owner is unwilling to do this, it becomes the responsibility of the conservator to make the arrangements.3 Torah scrolls, tefillin, and mezuzza scrolls should be left as they are. Once they are no longer in use, there is no reason for them to be kosher—in proper condition to be used—and therefore no reason why missing or abraded letters should be restored or minor repairs made to the parchment. As the texts of these documents never vary and they are never illustrated, aesthetic considerations are not relevant. If, for the safety of a Torah scroll, it is determined that repairs must be done to the rollers on which the scroll is mounted, these repairs shou be done by a scribe, who will then remount the parchment onto the roller in the traditional manner. A Torah scroll that has a tear in the parchment can be kept rolled to another part of the scroll. If two pages are separated, the two parts of the scroll should be wrapped and stored separately. If it is considered both possible (considering the condition of the parchment) and essential to rejoin the separated leaves, this work should be done only by a scribe. While they are in use, a pair of tefillin must be opened and examined periodically by a scribe to ensure that they are still ritually fit. Once they are no longer in ritual use, they should be left as they are. Undamaged tefillin should never be opened in a museum. The texts inside an already damaged pair of tefillin may be removed and examined, as the style of the writing may give clues to the time and place in which they were written. Tefillin may be exhibited in a damaged condition if there is some reason to do so, such as association with a famous person, or in an exhibit of Holocaust material. Alterations of any kind to an object that survived the Holocaust, unless absolutely necessary to ensure its physical survival, are inappropriate. Repair of other books and documents, when done with the respect that should characterize any professional conservation treatment, is entirely appropriate. In Judaism, study of traditional texts is considered to be the equivalent of prayer. To restore any text, whether of aesthetic or historical value or not, to a state in which it can be studied is an act of merit whatever the religious or cultural affiliation of the person doing the work. When Torah scrolls, Bibles, prayer books, or volumes of the Talmud are in the possession of a Jewish institution or a traditional Jew, photography (or making photocopies) of open scrolls or pages is normally permitted only for serious study or publication, as the copies are considered to be the equivalent of the book or scroll itself and should be disposed of in the same way once they are no longer needed. Once the books and other documents are in a secular library or archive, the rules of the institution apply. These rules are usually based on condition and value, but restrictions on casual copying would be appropriate in all cases. The person obtaining the copies should be informed of the proper procedures for disposal, and the institution should offer to perform this service if the person returns the material. |